Colt-Paterson Model 1836 Revolver

Patented on Feb. 25, 1836, Samuel Colt’s five-shooter—the world’s first commercially practical revolver—took its name from the factory where it was mass produced, the Patent Arms Co. in Paterson, New Jersey. It met with a lukewarm reception until 1839, when Colt added an integral loading lever and capping window that made reloading far easier and faster.

The U.S. Army purchased a limited number of Colt’s revolving pistols, rifles and shotguns for field testing in Florida during the 1835–42 Second Seminole War, but rejected them as too fragile and prone to malfunction. Colt improved the breed. By 1843 the Republic of Texas Navy had bought 180 rifles and shotguns and a roughly equal number of revolvers. When the Texas Army and Navy were disbanded that year, the republic’s remaining armed force, the 40 men of the Texas Ranger Company, bought up the surplus revolvers.

Ranger Capt. John Coffee Hays heaped praise on the weapons for their relative ease in loading from virtually any position and their effectiveness against larger numbers of Indians. By 1861 Colt’s continually improving revolvers had won their way back into the U.S. military, whose officers would soon be trading shots with each other.

Minié Bullet

In 1847 French armorer Claude-Étienne Minié developed a conical bullet with cannelures around the sides that would expand upon firing. This feature allowed a line infantryman to quickly secure the round within a musket barrel—even one with rifling—after which the hot gasses of the powder explosion caused the bullet to expand as it spun out the rifled barrel. This gave the bullet or “Minié ball” greater speed, range and accuracy than the older musket ball yet could be loaded/reloaded just as fast.

A further refinement was introduced by Capt. James H. Burton of the Harpers Ferry Armory in western Virginia, in the form of a conical concavity at the rear, aiding the bullet’s expansion. Britain’s army first took full advantage of the Minié bullet with its Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle, which entered service during the Crimean War. The American variant was incorporated into the Model 1855, whose Maynard tape primer was replaced by a copper cap in the Model 1861 Springfield, so named because most (but by no means all) were produced in that Massachusetts town. The rifled Minié bullets were devastating in both wars. Their users still clung to Napoleonic Era century doctrine, facing off in lines and at distances for which casualties to more efficient rifles increased exponentially.

Dévastation Class Ironclad Floating Batteries

The ironclad warship harkens back to the Korean “turtle ships” that helped defeat the Japanese navy during the latter’s invasion attempt of 1592 to 1598. The concept was revived when France deployed three floating batteries of the Dévastation class to the Crimean War. With their 4.3-inch-thick iron sides, 16 50-pounder smoothbore and two 12-pounder guns, the vessels weighed more than 1,600 tons each and although powered by a 150-hp Le Creuzot steam engine each or the wind against three auxiliary sails, the best speed they could produce was 4 knots. Consequently, in practice the vessels had to be towed to their targets by sidewheeler steam frigates: L’Albatros for Dévastation, Darien for Tonnante and Magellan towing Lave. The trio had their combat debut against the Russian fortress of Kinburn on the Black Sea on Oct. 17, 1855, performing well as Dévastation hurled 1,265 projectiles on the fort (82 of them shells) in four hours, sustaining 72 hits, 31 of which struck its armor and suffering the only fatalities of the three: two crewmen—plus 12 wounded. All three batteries saw further service against the Austrians in the Adriatic Sea in 1859.

That year the French commissioned Gloire, the first seagoing ironclad, ushering in a new era in warship design, which would next see practice in earnest when the Confederate ironclad ram Manassas defended New Orleans on Oct. 12, 1861 and—vainly—on April 24, 1862.

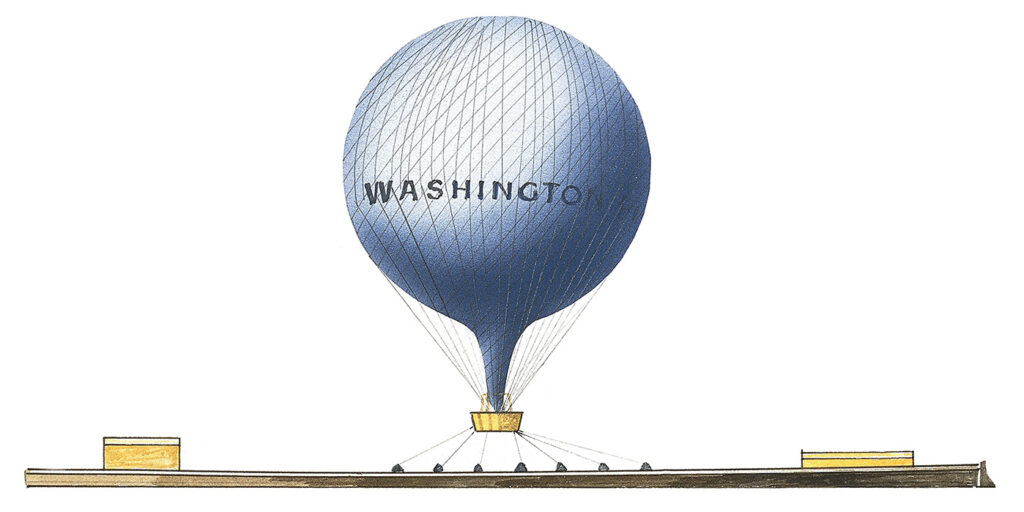

USS George Washington Parke Custis

In August 1861 Col. Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe, self-styled master of balloons, purchased a coal barge which he, in collaboration with John A. Dahlgren, commander of the Washington Navy Yard and chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, modified with a flat deck, 120 feet long and 14 feet, 6 inches in beam, capable of accommodating an observation balloon, hydrogen-generating apparatus, related equipment and tools and crewmen drawn from the Army. Although previous ships had carried balloons, Lowe’s vessel, christened USS George Washington Parke Custis, was the first designed from the hull up to maintain and launch them.

The one thing it lacked was its own means of propulsion. After trials on the Potomac River, on Dec. 10 the balloon carrier was towed downriver by the steamer Coeur de Lion, accompanied by Dahlgren and a detachment of troops led by Brig. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, anchoring at Mattawomen Creek. The next day Lowe ascended to observe Confederate activity in Virginia, three miles away, reporting on enemy batteries at Freestone Point and counting their campfires. George Washington Parke Custis accompanied the Army of the Potomac up the York and James rivers in spring 1862. Modest though its achievements were—limited by dependance on external propulsion—it was the first aircraft carrier.

Gatling Gun

The American Civil War coincided with the development of several automatic weapon designs, of which that of Dr. Richard Gatling, involving six rotating barrels cranked by hand, proved to be the most effective. Although patented on Nov. 4, 1862, the Gatling gun was not officially adopted by the U.S. Army until 1866…which is not to say it saw no action until then. On July 17, 1863 city authorities purchased some Gatlings to intimidate anti-draft rioters in New York. During the siege of Petersburg (June 1864-April 1865) Union officers bought 12 Gatling guns with their own money to install in the trenches facing the Confederate defenses, while another eight were mounted aboard gunboats.

Although large and heavy, Gatlings made a growing post-Civil War presence in Japan’s Boshin War of 1877, the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War and the American charge up San Juan Hill in 1898. Eclipsed by gas-operated machine guns like the Maxim by the end of the century, the Gatling gun’s principle was revived in the late 20th century in electrically operated weapons such as the Vulcan minigun.

Spencer Repeating Rifle

In 1860 Christopher Miner Spencer patented the world’s first bullet contained in a metallic .56-56 rimfire cartridge. Using a lever action and a falling breechblock, it could quickly fire off seven rounds from a tubular magazine within the buttstock. The Union Army was hesitant to adopt the Spencer because of the logistic headaches entailed in supplying weapons that virtually invited rapid, potentially wasteful firing, but eventually Spencer persuaded President Abraham Lincoln that the advantages outweighed the problems. Its earliest appearance was with Col. John T. Wilder’s “Lightning Brigade” of mounted infantry, whose privately-purchased Spencer rifles were a factor in the Army of the Cumberland’s victory at Hoover’s Gap on June 26-28, 1863.

Back East, Brig. Gen. George A. Custer equipped half of his Michigan Brigade with Spencer rifles in time for the battles of Hanover on June 30 and Gettysburg’s East Cavalry Field on July 3. The first of the shorter, handier Spencer carbines appeared in August and made an immediate hit among the cavalrymen. If logistics constituted a problem for the Union troops, it was worse among the Confederates whenever they obtained stocks of what they called “that damn Yankee gun that could be loaded on Sunday and fired all week.” Their shortages of copper and overall industrial capacity for reverse engineering rendered the captured Spencers a limited asset at best. A total of 200,000 Spencer rifles and carbines were produced before the state of the rifleman’s art advanced ahead.

Submarine H.L. Hunley

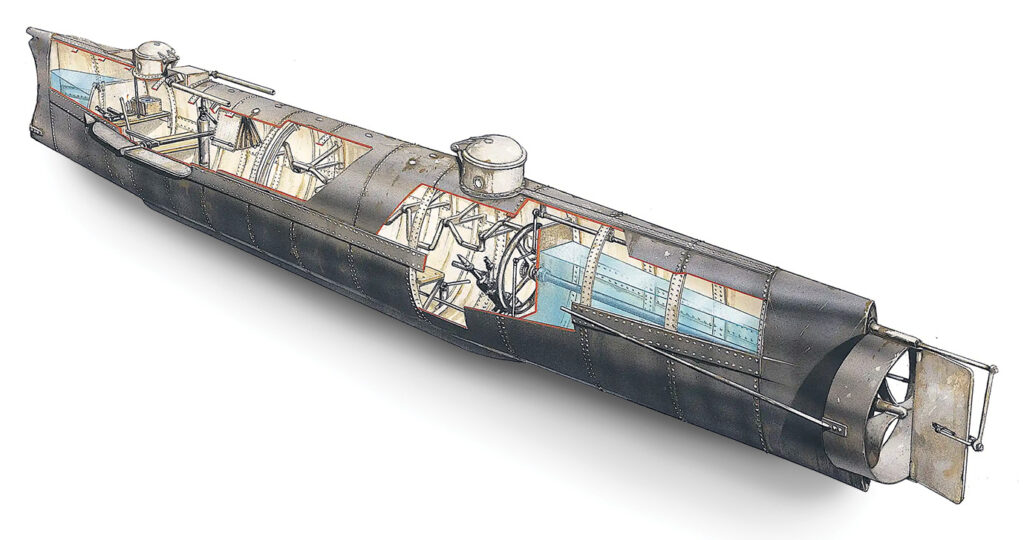

On Sept. 7, 1776 a curious little vessel called “Turtle,” designed by David Bushnell and manned by Continental Army Sergeant Ezra Lee, made history’s first submarine attack on the British 64-gun Eagle. The attempt failed and the next submarine attack on a warship had to wait until 1864. Under siege by land and by sea, Confederate-ruled Charleston, South Carolina used all manner of ingenious inventions to counter the overwhelming numbers of U.S. Navy blockaders, including the ironclad casemate rams Chicora and Palmetto State, small semisubmersible torpedo boats called Davids and a fully submersible vessel designed by Horace Lawson Hunley.

Propelled by a screw propeller turned by an eight-man crew and armed with a spar torpedo (explosive mine mounted at the end of a wooden pole), the latter was built in Mobile, Al. and shipped by rail to Charleston on Aug. 12, 1863. During testing on Aug. 29, the vessel, named H.L. Hunley for its inventor, swamped, drowning five of the crew. Raised and tested further, it sank again on Oct. 15, killing all eight crewmen including Hunley himself. Raised again, H.L. Hunley set out on its first operational sortie on Feb. 17, 1864 and detonated its spar torpedo against the side of the 1,260-ton screw sloop of war USS Housatonic, which sank. H.L. Hunley did not return, but in 1995 its remains were found and in 2000 it was raised, revealing it had ventured closer to its target than intended and swamped for the last time.

Although it took a heavier toll on its crews than on the enemy—a total of 21 killed compared to two officers and three crewmen slain aboard Housatonic—the precedent had been set by the world’s first successful submarine attack. The ill-starred H.L. Hunley is on display at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center on the Cooper River.

Dreyse Needle Gun

Developed by Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse and patented in 1840, the first breech-loading bolt-action rifle used a needle-like firing pin to pierce through a paper cartridge to strike a percussion cap at the base of the bullet. British testers were impressed by its accuracy at 800 to 1,200 yards, but dismissed it as “too complicated and delicate” to stand up to battle use—and in fact many Prussian infantrymen carried extra “needles” in case they broke. Despite the critics, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV ordered 60,000 for his army.

The Dreyse needle gun proved its mettle in the German wars of reunification, while evolving from paper to metal cartridges in 1862. The rifle was first used against fellow Prussians in the May uprising in Dresden during the Revolution of 1848, but truly proved itself against Danish muzzle-loaders in the Second Schleswig-Holstein War of 1864. The Prussians had 270,000 Dreyses for the Seven Weeks’ War of 1866, where the average Prussian infantryman could get five shots off lying prone in the time it took an Austrian standing to reload his Lorenz rifle musket. The Dreyse met its match in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 against the superior French Chassepot, but with 1,150,000 needle guns, the better-led Prussian forces prevailed.

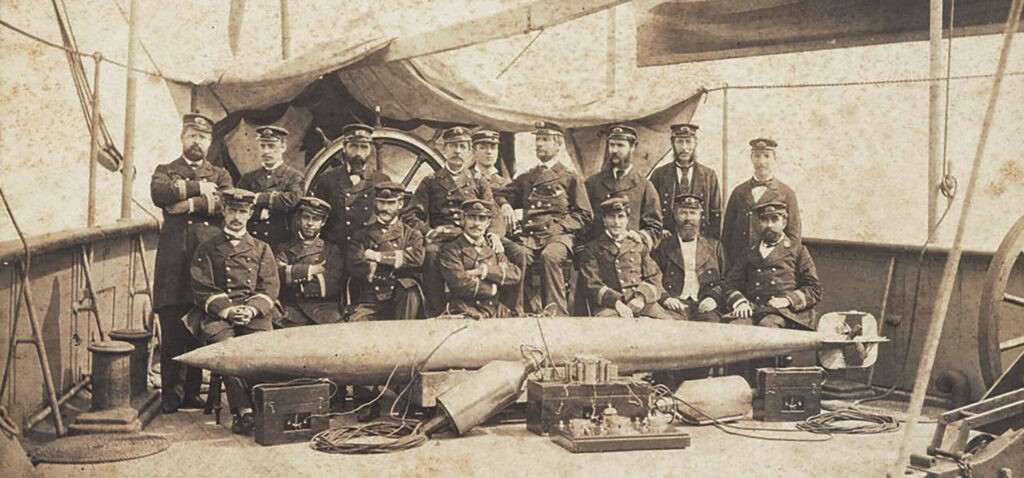

Whitehead Locomotive Torpedo

In the Austrian port of Trieste in 1860, naval engineer Robert Whitehead, was inspired by Fiume-based engineer Giovanni Luppis’ “coast savior,” a small self-propelled vessel run on compressed air. He designed a compressed air-powered “Minenschiff” also called a “locomotive torpedo,” patented on Dec. 21, 1866. Unlike previous stationary torpedoes, Whitehead’s was not only self-propelled, but had a self-regulating depth device and a gyroscopic stabilizer. Equally important, Whitehead devised a launching barrel, making his invention not a merely a weapon, but a weapons system. After being test mounted on the gunboat Gemse, Whitehead’s torpedo was purchased or licensed by 16 naval powers, undergoing constant refinement.

Its essential nature in one role was expressed by Adm. Henry John May in 1904 when he declared, “but for Whitehead the submarine would remain an interesting toy and little more.” The first wartime torpedo attack allegedly occurred during the Russo-Turkish War on Jan. 16, 1878 when torpedo boats from the Russian tender Velikiy Knyaz Konstantin captained by Stepan Osipovich Makarov sank the Ottoman steamer Intibah. After all the improvements the original underwent, its last combat use came in Drobak Sound, Norway on April 9, 1940 when two Whitehead torpedoes from a Norwegian coastal battery struck the shell-damaged German heavy cruiser Blücher and sank it.

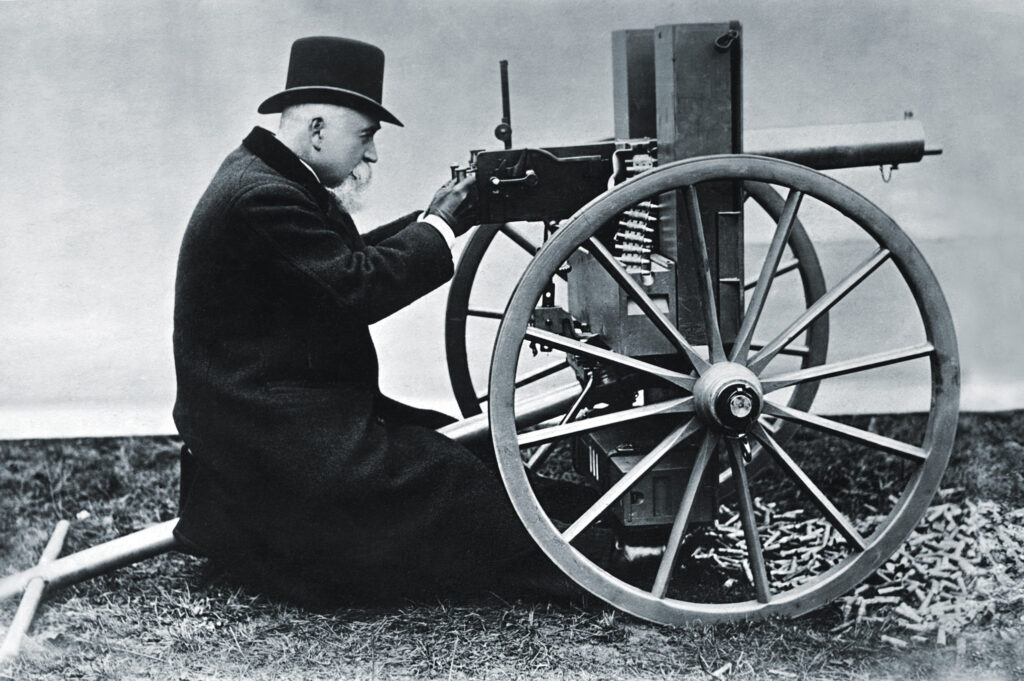

Maxim Machine Gun

Prolific polymath inventor Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim is best remembered for a three-year project begun in 1882 that led to a machine gun with a recoil-operated firing system that fired 250 .303-inch rounds at a rate the Gatling could not match, plus a water-cooling system to allow sustained fire. Its durability and murderous efficiency led to its use by 29 countries between 1886 and 1959. It also earned American-born Maxim a British knighthood. The Maxims’ effect on history first manifested itself in Africa, where the British used them in their 1887 expedition against rebellious Yoni in Sierra Leone and the Germans used them against the Abushiri of their East African colony in 1888.

Its first major battle was during the First Matabele War in what is now Zimbabwe. At Shangani on Oct. 25, 1893, 700 British and South African troops, backed by Maxims, took a fearsome toll on 5,000 Matabele enemies. In 1898 the weapon’s role in European and American imperialism was archly summed up by Hilaire Belloc in The Modern Traveler: “Whatever happens, we have got, the Maxim gun, and they have not.” The European powers would be forced to revise their view in 1914, however, when they had to face the consequences of using Maxim’s invention against one another.