In 1961, when U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara proposed the General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark as a Swiss army knife suitable for all three major flying services, that included a Navy version, the F-111B. The B turned out to be too complex, underpowered and heavy for carrier ops, however. It was also a bomber, and the Navy needed a fighter.

In the career-ending words of Vice Adm. Tom Connolly, in response to a senator’s question as to whether more powerful engines might make the F-111B acceptable, “Mister Chairman, all the thrust in Christendom couldn’t make a fighter out of that airplane.” Some claim that the Tomcat’s name is a tribute to Connolly’s falling-on-his-sword honesty.

The Navy was seeking a replacement for the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom, which no longer had the range or weapons needed to protect carrier battle groups. Soviet advances in bombers and anti-ship cruise missiles required an interceptor that could fly far and fast, with long loiter time, powerful radar and brutish missiles that could strike far beyond the range of Sidewinders and Sparrows.

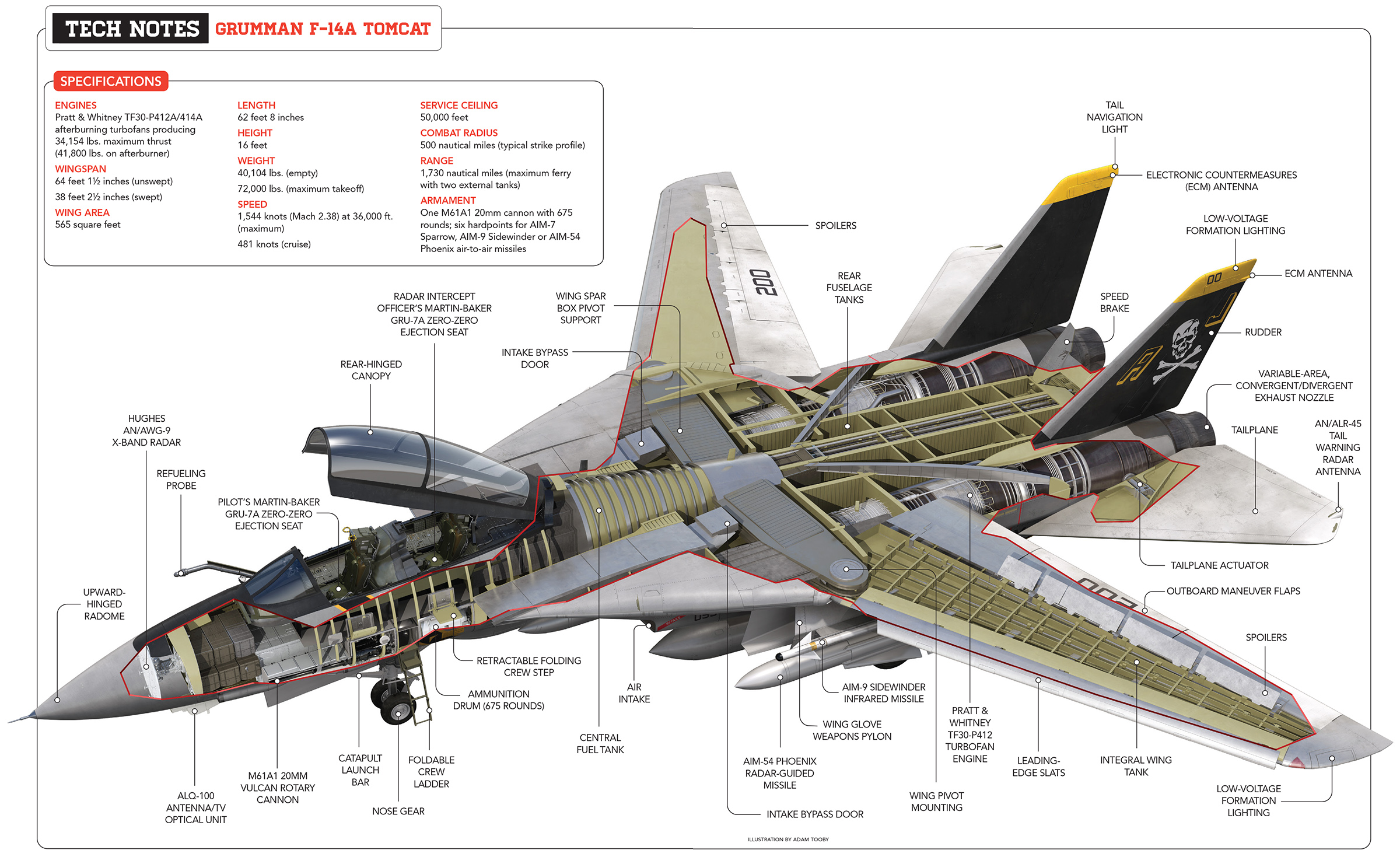

Grumman, which had worked with General Dynamics on the F-111’s variable-geometry wing, had already begun work on a fighter, the G-303, that became the Tomcat. It utilized the 111’s swing-wing concept as well as its Pratt & Whitney TF30 engines—unique in being the world’s first afterburning fighter turbofans.

Grumman, a swing-wing pioneer, had built the rotund and underpowered XF10F Jaguar to test the concept of a wing that could be unswept for carrier landings and takeoffs, and swept for inflight speed. Grumman test pilot Corky Meyer was the only person to fly the sole XF10F and he pronounced it fun “because there was so much wrong with it.” His work nonetheless carried over to the F-111 and the F-14.

The father of the Tomcat, Grumman engineer Mike Pelehach, saw his first MiG-21 at a 1960s Paris Air Show and knew the U.S. would need a fighter that could defeat it. Pelehach paced off the dimensions of the MiG and went back to the company’s Bethpage headquarters to begin work on a MiG-beater. Ultimately, he drew together all the concepts and options that resulted in the Tomcat.

A highly regarded engineer, Pelehach once had dinner with a group of his Chinese counterparts, who asked if it would be possible to modernize their own MiG-21s. Pelehach quickly sketched a design and some details on the tablecloth. At the end of the evening, the Chinese engineers stripped the silverware and took the tablecloth with them.

The variable-geometry wing, however, was not one of Pelehach’s best ideas. In practice the swing wing has been called a major aeronautical engineering blunder. On the Tomcat, it was complex and heavy, and though its movement was automatic and rapid, some Air Force F-15 and F-16 pilots who flew against the F-14 claimed the wings’ position telegraphed the airplane’s energy state as it lost momentum during air combat maneuvers. The main reason for that lost momentum during ACM was the dismal .68-to-1 thrust ratio of the early TF30 engine.

The fuel-efficient engines (plus swing wings that could be unswept at max-loiter airspeeds) allowed the Tomcat to linger longer over the battlefield, with a bigger ordnance load than any fighter in the world, but they had a failing that had already cropped up during the F-111’s career. F-111s weren’t expected to fly as extreme a flight envelope as were Tomcats, so the problem was not a major consideration. But the fact remained that TF30s were never intended to be fighter engines; they were not meant to deal with the constant and rapid throttle movements and high angle-of-attack situations that modern combat involved.

The TF30 was prone to compressor stalls and surges when operated at high angles of attack or yaw if the power levers were moved too aggressively—common during air combat maneuvering. The Tomcat’s engines were mounted about nine feet apart, to allow room between them for missile carriage and to create a large lifting surface. (More than half of an F-14’s total lift comes from what Grumman called the pancake—the surface area between the engine nacelles.) So when one of the engines lost power from a compressor stall, the resultant yaw could be sudden and scary, sometimes resulting in an unrecoverable flat spin. Compressor stalls led to the loss of more than 40 F-14s. Had the early Tomcats ever gone into serious combat, more of them might have been lost to compressor stalls than to enemy action.

Some Tomcat crews described their mount as “a nice aircraft powered by two pieces of junk.” For the sake of airframe longevity, the Tomcat was in practical terms limited to 6.5 Gs, while an F-15 could pull 9 Gs. (So could a Tomcat, at high enough speeds, but the airplane then had to undergo a complex over-G inspection.) The difference was also attributed to TF30 engine limitations.

Recommended for you

The F-14 was a difficult airplane to handle in the final stages of a carrier landing, in part because of its tendency to hunt laterally while trying to achieve a stabilized approach. The fact that the F-14 had spoilers rather than ailerons didn’t help, nor did its high pitch inertia, which made it float during the final stages of an approach. (These problems were ultimately corrected when Tomcats were fitted with digital flight-control systems.)

The TF30 was never intended to be the F-14’s duty engine. It was used simply to get the Tomcat project airborne and into flight test and initial service. The TF30 was to be replaced by an ephemeral Advanced Technology Engine that was being developed for the F-15—the Pratt & Whitney F401. The ATE never materialized, so Tomcats sailored on with the TF30 until near the end of the production run, when a good General Electric engine, the F110, became available and created the F-14D as well as some retrofitted A models that were labeled F-14A+ (later redesignated F-14Bs).

In 1984 Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, a former naval aviator, said the TF30/F-14 combo was “probably the worst engine-airplane mismatch we have had in many years. The TF30 is just a terrible engine….”

![An F-14 carries four AIM-54 Phoenix missiles under its fuselage, along with AIM-7 Sparrows and AIM-9 Sidewinders on wing hardpoints. (PF-[aircraft]/Alamy)](https://www.historynet.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Tomcat-missiles-960_640.jpg)

The Tomcat was built around an enormous super-missile, the AIM-54A Phoenix, which weighed almost half a ton, was 13 feet long and 15 inches in diameter and cost half a million dollars to fire. At the time it was the most sophisticated and expensive air-to-air missile in the world. The Tomcat could carry six, but since four was the most that could be brought back to the ship, that was the normal loadout. The Phoenix was originally designed for use against slow-moving bombers with huge radar signatures and it wasn’t nearly as much of a threat to fighters with savvy pilots.

The F-14 was the only aircraft ever to use Phoenixes operationally. In a carefully orchestrated live-fire test, a Tomcat loosed all of its Phoenixes within 38 seconds at a distant skyful of pilotless airplanes and target drones. One of the missiles failed, but of the five that flew, four scored direct hits and the fifth detonated near enough to its target to be considered a “lethal miss.” Unfortunately, combat is not so carefully orchestrated. In January 1999, a pair of Tomcats fired two Phoenixes at Iraqi MiG-25s south of Baghdad. Both missed. Eight months later, an F-14 launched a Phoenix at an Iraqi MiG-23. Again, it missed as the target fled. It was the last time the Navy ever fired a Phoenix in anger.

Had the live-fire test been a failure, the Tomcat program might have been aborted, since it was already in trouble from cost overruns, schedule slippage and several test-flight crashes. The most notorious crash took out the first prototype on only its second flight, when a vibratory failure of all three hydraulic systems—main, backup and a limited “combat backup” system—rendered the airplane uncontrollable on short final to Grumman’s Calverton, Long Island, airfield. The crew ejected and came within an ace of parachuting into the Tomcat’s fireball.

The Phoenix followed an eject-launch flight path rather than being rail-launched. “Firing” it meant dropping it like a bomb, since its powerful engine needed to be well below the F-14 before igniting. Once the solid propellant lit off, the Phoenix immediately soared to 80,000 feet and accelerated to Mach 5 toward its target. Above that target and coasting, the Phoenix dove steeply down on it, substituting kinetic energy for the spent force of its motor.

The Phoenix’s maximum range has been quoted as 125 miles, but effectively it was somewhat less. Target acquisition and missile launch assumed that the two aircraft were beak-to-beak at high speed, so the actual impact would take place when the Tomcat’s opponent was substantially closer. An effective Phoenix countermeasure was to simply turn away from the missile and let it expire, assuming an attacker had an accompanying AWACS-type overseer to call out the Phoenix launch.

An essential component of the Phoenix system was the F-14’s planar-array Hughes radar. When the Tomcat went into fleet service, the yard-wide AWG-9 dish was capable of tracking 24 targets simultaneously and directing missiles at six of them. At the time that was unprecedented, but the Hughes radar was still a complex, hard-to-maintain, 1960s analog system.

The early Tomcat’s avionics, including the radar, badly needed upgrading to include high-speed multiplex digital data busses, multifunction cockpit displays, head-up displays and other state-of-the-art features already common in the Air Force’s fourth-generation fighters, the F-15 and F-16. The Tomcat was increasingly an analog airplane in a digital age. The advent of the F-14B and then the F-14D solved those issues.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The D model was in fact an all-digital strike fighter. It carried a remarkable new radar “that gave it an enormous increase in effectiveness…against stealthy aircraft,” wrote Rear Adm. Paul T. Gillcrist in his comprehensive book Tomcat!“Its capability against all types of targets in an electronic warfare environment [was] vastly improved.” The F-14D also had IRST (Infrared Search and Track), a passive sensor that was accurate at shorter ranges and almost impossible for opponents to detect. The fighter’s new glass cockpit, digital avionics and greatly enhanced datalink increased the crew’s situational awareness. The F-14D was a true multi-mission aircraft and its proponents believed it was a better strike fighter than the vaunted F-15E Strike Eagle. Unfortunately, the F-14D didn’t reach the fleet until 1990, a year before Tomcat production was defunded, and only 37 units were built.

As it was, the complex F-14 was difficult to service and maintain aboard carriers. Most estimates held that Tomcats required anywhere from 30 to 60 hours of maintenance per hour flown—about three times as much as the F/A-18 Hornets that replaced them. One result was that Grumman, Hughes, Raytheon and other companies sent civilian tech reps to carriers to do the heavy lifting, which gave the Navy’s own sailors too little opportunity for on-the-job training.

The F-14 was assigned to fleet defense but its main task became establishing air superiority, and it took on the duties of an interceptor and tactical attack fighter with all-weather capability and great range. With excellent visibility (the Tomcat was the first U.S. fighter since the Korean War with a 360-degree-view canopy), 20mm cannon, automatic maneuvering flaps and dogfight radar mode, it was well suited to the task. Recon capability followed as the Navy phased out its Vought RF-8 Crusaders and North American RA-5 Vigilantes. Toms were fitted with big belly pods called TARPS (Tactical Air Reconnaissance Pod System). A TARPS was more than 17 feet long and weighed almost a ton, filled with electronic and photo-snooping gear.

The final iteration of the F-14 was nicknamed the “Bombcat.” It was fitted out as a fighter-bomber intended to serve as a self-escorting ground-attack aircraft. The Bombcat saw more action over the Balkans, Iraq and Afghanistan against the Taliban and al Qaeda than the F-14 ever did as an air-superiority fighter.

Were it not for the Shah of Iran, there might never have been an F-14. Iran was the only foreign country ever to operate Tomcats, and it does to this day. The Iranians purchased an armada for $2 billion in 1974—at the time the single highest-value sale of military equipment in U.S. history—back when the shah was one of America’s few allies in the Mideast. But he had to make sure Grumman stayed in business in order to get his airplanes.

The company had signed a fixed-price contract with the Navy to produce the fighter, but the early 1970s were an inflationary time, and the price of materials—particularly titanium—rose so rapidly that Grumman was at one point losing a million dollars on each Tomcat it built. Things looked bad for the airframer, until the shah stepped in with a $75 million loan.

The shah wanted the Grumman product, but a flyoff against the F-15 Eagle had to be arranged to at least give the appearance of a competition. The F-15, besides being the darling of the Air Force fighter community, had a higher thrust-to-weight ratio and would have outperformed the Tomcat, all things being equal.

But they weren’t. A coin toss allowed the Air Force crew to fly first, and while they did, the F-14 sat waiting its turn on a distant run-up pad. The pilot had set his power levers as far forward as he dared, and while the Eagle flew its strictly defined 12-minute program, he burned off part of his fuel load and took off a good bit lighter than the demo rules had postulated.

The Grumman crew had also noted during its weather briefing that there was a distinct wind shear at 1,000 feet, with the flow nearly reversing itself from what was happening on the ground. So they flew their demonstration pattern in the opposite direction from what the Air Force had done, and their slow-flight passes abeam the shah’s viewing bleachers appeared far more graceful than the Eagle’s, thanks to the headwind. The shah was sold.

Delivery of the Iranian Tomcats began in 1976, accompanied by 284 Phoenix missiles. The Iranians had far better results from Phoenix launches, shooting down dozens of Iraqi opponents during their 1980s war.

Three years later, the shah was deposed and the F-14s became the property of the Iranian revolutionary air force. Seventy-nine of the 80 purchased, plus the missiles, had been delivered, but most of them soon became unflyable. The U.S. refused to support the complex airplanes and Iran quickly ran out of spare parts. Hangar queens were cannibalized and eventually only a dozen Iranian F-14s remained flyable.

Beginning in the late 1990s, illicit F-14 parts were finding their way from the U.S. (and Israel) to Iran. In 2007 federal agents seized four intact Tomcats in California. Three were in museums and a fourth was in the hands of the TV series “JAG,” which used the airplane in ground scenes numerous times. The stir ultimately resulted in the destruction of virtually all of the 150-odd retired Tomcats parked at the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base boneyard.

Today, however, Iran has put some 40 Tomcats back in the air carrying an improved Iranian version of the Phoenix, thanks to advances in the country’s capabilities and the use of such technologies as 3D printing for the manufacture of spares. They are the only active F-14s in the world. Many are virtually new, having been unflown for decades. But they’d be no match for F-22 Raptors or F-35s, or even Navy F/A-18 Hornets and Super Hornets.

For all its faults, no airplane has ever done as much for the Navy as a recruiting tool as did the Tomcat—not even the Blue Angels’ various mounts. The Blues never flew F-14s, which were far too expensive to maintain for a noncombat PR team, nor were their swing wings adaptable to close-order formations. In the year after the 1986 Tom Cruise film Top Gun was released, Navy recruitment jumped by 500 percent, and the sea service added an unexpected 16,000 uniformed personnel to its ranks. Every air-minded kid in the country wanted to grow up to fly a Tomcat.

Like James Bond’s Aston Martin, the Tomcat’s cinematic notoriety considerably exceeded its real-world accomplishments. The program was canceled in 1991 after 712 units had been manufactured, versus 5,195 of its F-4 predecessor and 1,480 of the F/A-18 Hornet successor (both of which have flown in more than one U.S. military branch and multiple foreign services).

The demise of the Tomcat meant the end of Grumman as an airframer. The company was bought by Northrop in 1994 and found itself in the space and electronics business, leaving the Navy with Boeing, which had merged with McDonnell Douglas, as its sole-source fighter supplier.

No matter how many Top Gun fans proclaimed that the Tomcat was “so cool,” nothing could save even the much-improved F-14D. Proving once again that coolness is not a mission requirement.

For further reading, contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends: Grumman F-14 Tomcat Owners’ Workshop Manual, by Tony Holmes; F-14, by Mike Spick; Tomcat! The Grumman F-14 Story, by Rear Admiral Paul T. Gillcrist; and F-14 Tomcat, by David F. Brown.