“I reported in pictures what I saw with my own two eyes, wide open.”

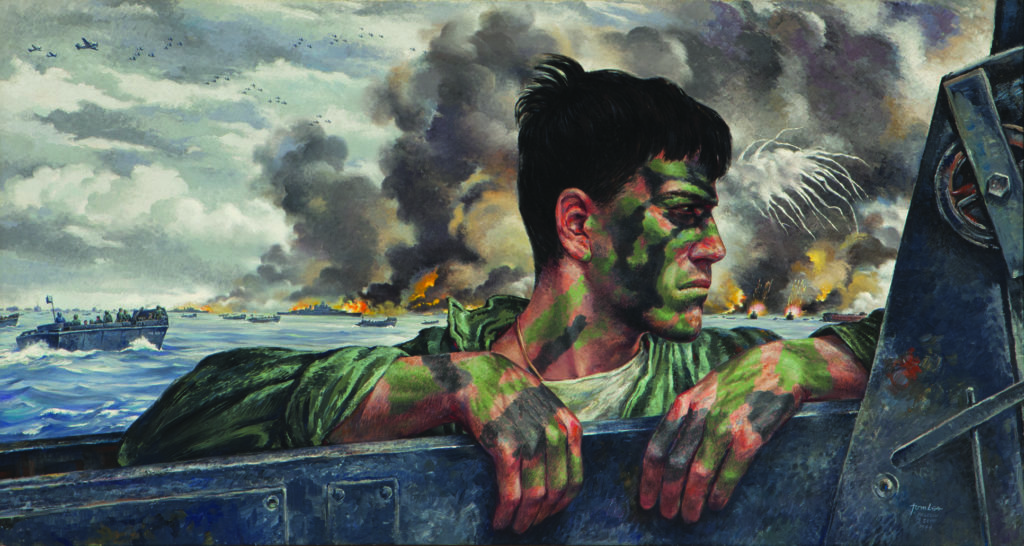

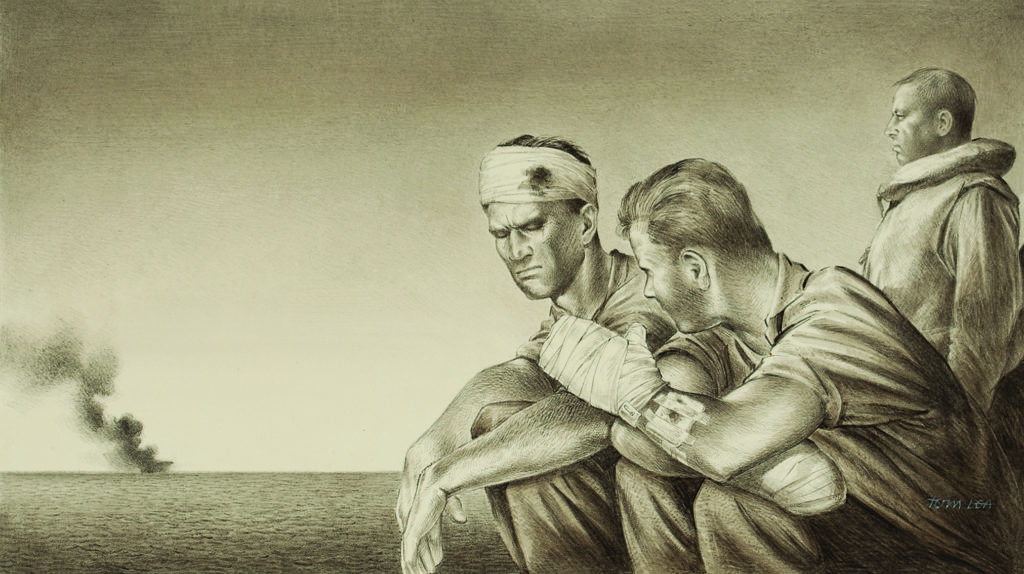

It’s been said that if you look into an infantryman’s eyes you can tell how much war he has seen. Gaze into the eyes of the warriors portrayed by World War II combat artist Tom Lea and you know that his subjects have seen hell.

Thomas Calloway Lea III (1907-2001) covered the war for Life magazine, a publication that prided itself on being a photographer’s journal. Yet the editors at Life knew Lea’s paintings captured something the camera lens could miss: his affinity for the men he covered, combined with a relentless pursuit of accuracy.

“I did not report hearsay; I did not imagine, or fake, or improvise; I did not cuddle up with personal emotion, moral notion, or political opinion about War with a capital W. I reported in pictures what I saw with my own two eyes, wide open,” Lea stated.

He was also a talented writer whose dispatches were frequently published alongside his artwork. Combined, his paintings and his words are among the most potent testimonials about the suffering of ordinary men to emerge from the war.

A native of El Paso, Texas, Lea studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, then traveled to Paris where he fell in love with the work of the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix. During the Great Depression, he considered himself fortunate to paint murals for the federal Works Progress Administration that decorated U.S. Post Office buildings in Texas and a Treasury Department building in Washington, D.C.

Lea’s association with Life started in 1941 when he and six other artists were assigned to fan out across the nation and capture what the magazine called the “period of national defense.” The Pearl Harbor attacks were still months away, but the U.S. government had launched the first peacetime draft authorized by the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940; Lea painted and sketched men of the prewar army who would eventually shape civilians into soldiers.

Lea’s work impressed Dan Longwell, Life’s managing editor, who asked if he would be interested in an assignment covering the U.S. Navy’s North Atlantic Patrol that protected supply ship convoys heading to Great Britain. By November 1941, the navy granted Lea full access to the fleet, allowing him to live and work among the sailors battling German U-boats during the so-called Neutrality Patrol. But his experience with neutrality was short-lived; Lea was aboard the destroyer tender USS Prairie when he and the sailors received word of the Pearl Harbor attacks.

After the United States declared war on the Axis powers, Lea received additional Life assignments that made him one of the few American artists who covered multiple theaters of action. He sketched and painted life onboard the USS Hornet off Guadalcanal in 1942, Allied operations in China, and U.S. Marines assaulting Peleliu in 1944.

His penchant for sharing the same risks as fighting men meant he narrowly escaped death several times. “On the beach, I found it impossible to do any sketching or writing,” Lea wrote about his landing on Peleliu during the Marines’ assault. “My work there consisted of trying to keep from getting killed and trying to memorize what I saw and felt under fire.”

After the war, Lea’s portraits and murals graced university museum collections, the Oval Office, and the Smithsonian. He also wrote two novels that are regarded as classics of American literature of the Southwest. But as long as he worked, he kept in his Texas studio the same Marine Corps Ka-Bar knife he carried with him on Peleliu. Lea used it to sharpen his sketching pencils. ✯

All images: U.S. Army Art Collection, U.S. Army Center of Military History, except where noted.

This article was published in the June 2020 issue of World War II.