On March 15, 1939, German troops marched through Prague’s historic Wenceslas Square and occupied what was left of the Czechoslovak Republic—only six months after British prime minister Neville Chamberlain had bartered the Sudetenland to Adolf Hitler for “peace in our time.” The next day, Hitler stood at Prague Castle to proclaim that the nation was now the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. This site, which overlooks one of Europe’s most beautiful cities from its imposing ridge above the Vltava River, was charged with symbolism. For more than 1,000 years it had been the seat of government for kings of Bohemia, Hapsburg emperors, and the republic’s presidents. Right after Hitler’s speech, his former foreign minister Konstantin von Neurath took office as Reichsprotektor and set up his Nazi administration there.

Hitler appointed Neurath, whose long pre-Nazi government service earned him some international respect, to help ease the sting of annexing the rump state so soon after the Munich Agreement. But Neurath quickly banned political parties and trade unions, and installed the Nazis’ Nuremberg Laws, which stripped Jews of their rights and property and livelihoods. On October 28, he ordered German police to attack a Czech Independence Day rally in Wenceslas Square, which spawned anti-Nazi demonstrations while Czech police watched. Jan Opletal, a medical student, was shot in the stomach and died in slow agony; his funeral brought thousands of angry students back into Prague’s streets. Hitler demanded brutal reprisals, and Neurath obliged. He executed nine students, sent 1,200 more to concentration camps, and closed all universities.

One warm spring afternoon, I sat at a Wenceslas Square café, sipping a pilsner and people-watching; the half-mile-long space is lined with restaurants, hotels, and shops, and anchored by the monumental National Museum. Here, I knew, the 1989 Velvet Revolution began, inspired by the 1939 clashes, and toppled the Communist regime. I also remembered that despite his crackdown, Neurath proved too gentle for Hitler. So on September 27, 1941, Reinhard Heydrich, the SS golden boy with the iron fist, arrived to rule from the castle.

Today, Prague Castle—actually a huge rambling area enclosing the Royal Palace, St. Vitus Cathedral, churches, convents, monasteries, museums, offices, shops, and housing—welcomes herds of visitors. Early one morning, I meandered across the ancient Charles Bridge over the Vltava, then wound through the Malá Strana, the “Little Quarter,” to climb the old castle steps. On my must-see list was a small house that Franz Kafka shared with his sister Ottla in 1922; his stay inspired The Castle, his surreal novel in which a labyrinthine, Hapsburg-like bureaucracy keeps the populace divided and cowed. Kafka, a Jew, died in 1924, but Ottla lived to see the Nazis. She was sent to Theresienstadt, a “model village” for Jews used for propaganda purposes. Beneath its warm façade, Theresienstadt was a transit camp where 35,000 Jews died and 80,000 more were deported eastward—including Ottla, who died in Auschwitz. Kafka’s other two sisters also perished in camps.

Through a nearby gate in the castle’s wall, I walked into the gardens to see Prague unfold, straddling the river’s bends, stretching to the horizon. The spidery streets and Parisian boulevards and bridges stitch together a riot of architectural styles: gothic, baroque, Arabesque, neoclassical, art nouveau, Stalinist Bauhaus, postmodern (a wacky Frank Gehry design by the river was originally called Fred and Ginger, after Astaire and Rogers). Prague, I thought, has a history and culture as unique and jumbled as its skyline.

The Czechs have been their own masters for only about 50 of the last 500 years. Of the foreign overlords who reigned in the castle, the Nazis had the shortest stay. The Hapsburgs absorbed the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1526, and held sway until 1918 when the Versailles Conference created the Czechoslovak Republic, which lasted barely 20 years. The coalition governing the republic after World War II collapsed in a 1948 Communist coup ordered by Stalin. Moscow managed the new satellite state until 1989, when the deep underground streams of patriotic fervor that had kept Czech culture and dreams of independence alive for centuries finally burst free.

The Czechs have been their own masters for only about 50 of the last 500 years. Of the foreign overlords who reigned in the castle, the Nazis had the shortest stay. The Hapsburgs absorbed the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1526, and held sway until 1918 when the Versailles Conference created the Czechoslovak Republic, which lasted barely 20 years. The coalition governing the republic after World War II collapsed in a 1948 Communist coup ordered by Stalin. Moscow managed the new satellite state until 1989, when the deep underground streams of patriotic fervor that had kept Czech culture and dreams of independence alive for centuries finally burst free.

Jews were a vital component of Prague life almost from its start. Originally they lived in the old ghetto, today called Josefov. Despite 19th-century urban renewal, its narrow streets are still rich with historical sites. By the 17th century, Prague was Europe’s second-largest Jewish center, with 15,000 Jews—nearly a third of its population. By the 19th century, Jews had mostly assimilated and often lived outside the old ghetto, many becoming prosperous and influential.

That would change, of course, with the arrival of the Nazis. On June 22, 1939, Adolf Eichmann moved into a confiscated Jewish villa in Prague’s Str?es?ovice district. Eichmann ran the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, which aimed to fleece the Jews of all they owned and force them to flee. Soon there would be a far darker plan. In January 1942, Eichmann joined Heydrich at a conclave in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee, where they worked out the Final Solution.

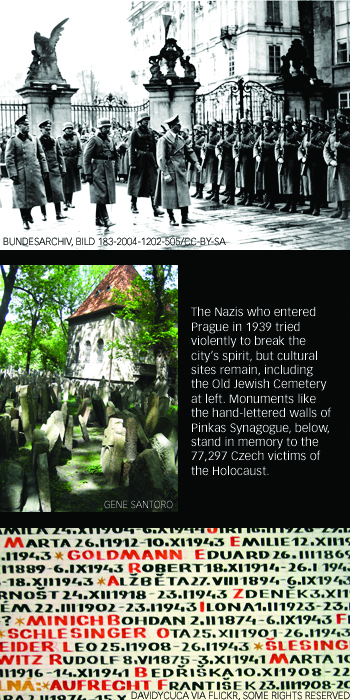

But in the meantime, Reichsprotektor Heydrich focused on eradicating Czech resistance and culture. His long-term plan was to either kill or banish to the east two-thirds of the Czech population. German settlers would take their place. But before doing that, Heydrich aimed to crush the Czech spirit. His first three days brought 92 executions. Within four months, thousands of Czechs had been killed or thrown into prison. Heydrich was soon dubbed the Butcher of Prague. Resistance was smashed; the city stayed quiet even when the Nazis conscripted tens of thousands of workers for German factories. In May 1942, partisans assassinated Heydrich in a Prague suburb. In reprisal, the Germans razed the entire town of Lidice and massacred its people. Some 13,000 more were arrested, deported, or imprisoned.

By then, tens of thousands of Jews had suffered the same fate—and the Holocaust Heydrich had masterminded (named Operation Reinhard in his post-humous honor) began in earnest. Some 360,000 Jews had lived in the interwar Czechoslovak Republic. By 1945, about 263,000 were dead; 14,000 remained.

By then, tens of thousands of Jews had suffered the same fate—and the Holocaust Heydrich had masterminded (named Operation Reinhard in his post-humous honor) began in earnest. Some 360,000 Jews had lived in the interwar Czechoslovak Republic. By 1945, about 263,000 were dead; 14,000 remained.

One rainy day, I spent hours at the Old Jewish Cemetery, crammed with 12,000 gravestones, and at the Maisel, Pinkas, and Spanish Synagogues. These gorgeously restored buildings house exhibits detailing Czech Jewish history—an ironic gift from the Nazis. In 1942, the Nazis formed a Jewish committee to gather materials from 153 congregations for a new Central Jewish Museum. The elders went to work, unaware the facility was actually meant to be a “museum of vanished peoples”: it would be all that was left of the Jews after the Final Solution. I was especially moved at Pinkas, an art nouveau structure with arched gothic ceilings. Its downstairs walls are hand-lettered with the names of 77,297 Holocaust victims. Upstairs, astonishing drawings, paintings, and poems by the children consigned to Theresienstadt, that model village, are heartbreaking testimony to the human spirit.

When the sun came out late that afternoon, I walked to Old Town Square to clear my head. Here crowds gather on the hour to take pictures of the town hall’s 15th-century astrological clock with its delightful mechanical figures in motion. I sat down at a café and watched crews setting up two JumboTrons and food booths for the broadcast of a soccer tournament match between the Czech Republic and Russia. That weekend, several thousand Czechs and visitors packed the square to cheer the action while devouring grilled sausages and fire-roasted pork sandwiches and pastries and original Budweiser. It was like a giant tailgate party on an antique set. When the Czechs beat the Russians, the square erupted. I remembered the 1968 Prague Spring, crushed by Soviet tanks, and hoisted my pilsner to toast the rebirth of this vibrant city.

Gene Santoro is the World War II reviews editor. He loves Czech writers, and Czech New Wave and animated movies. He first saw Prague in bleak 1979. When he went back recently, it had been transformed into a world capital and tourist center.

When You Go

Delta flies nonstop from New York to Prague five times weekly.

Where to Stay and Eat

Cafés abound for breakfast, lunch, and breaks. Among the most interesting are Café Kafka (Siroka 12), the Phenix Café (Smetanovo nabrezi 22), and Restaurace Jizera (Vaclavske nam 46). At Staromacek (Dlouha 4), try the potato soup, goulash, roast pork, or game dishes. At U dvou Slovaku (“At the Two Slovaks”; Tyska 10), the dumplings, sausage and cheese platters, soups, and pork dishes are as hearty as the frescoed dining room. Les Moules (Parizska 19) flies fresh mussels in from Belgium daily, and stocks Belgian beers. Café de Paris (Maltezske namesti 4) boasts excellent entrecôte steak (good beef is rare in Prague). Prague wouldn’t be Prague without beer halls. Pilsner was invented nearby, and is ubiquitous; local microbreweries still make their own. U Flek?u (en.ufleku.cz/; Kremencova 11) was founded in 1459, and its sprawling spaces and long, shared tables are an old-school treat. U Kalicha (Na bojisti 12-14) was immortalized in The Good Soldier ?Svejk, Jaroslav Ha?sek’s satiric World War I novel.

What Else To See

Kampa Island, wedged between the Vltava and the Devil’s Stream canal near the Charles Bridge, is a leafy enclave with museums, historic houses, mill wheels, and terrific vistas.