When I moved to Germany in 2005, I spent six weeks taking language classes in Kiel, a small city an hour’s train ride north of Hamburg. I had no idea when I first arrived that Kiel had once been a critical part of the German war machine—or that the city, situated along a long, wide fjord, had nearly been wiped off the map 60 years before. But my short time there was a lesson in more than grammar and vocabulary. It was also an introductory course in Germany’s ongoing struggle to deal with the legacy of World War II.

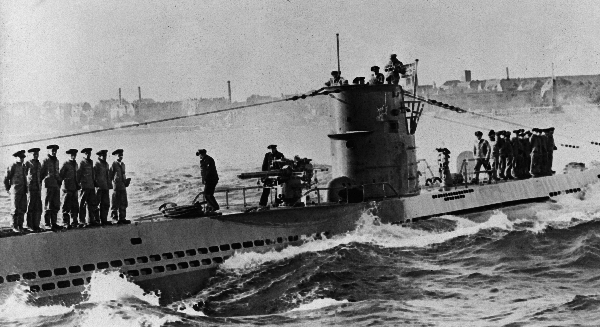

For more than a century, Kiel’s location on the Baltic has made it an attractive spot for the German navy, which still has a small base there. During World War II, Kiel’s importance grew. The town was where Germany’s deadly “Wolf Pack” of submarines was born, and the city became a major U-boat base and production center. The U-boat menace made Kiel a high-priority target for Allied bombers. By the end of the war, the town had been pummeled so many times—there were almost 100 heavy raids on Kiel between 1940 and 1944—that 80 percent of the town’s buildings were destroyed and 167,000 people were homeless.

Today, Kiel is a quiet city known for its university and excellent sailing. Cruise ships and ferries glide in and out of the fjord, docking just across from the train station downtown. At first glance, there’s not much left of the city’s wartime identity. But in the last decade, Kiel has carefully begun to deal with its past. On a rainy May morning, I return to Kiel to see how the town remembers its wartime history. I find three monuments, each with a different tale to tell.

A few steps from Kiel’s train station is a ferry dock. Every hour, big boats chug up the fjord. I catch one heading north; after half an hour, it pulls up to the little beach town of Möltenort. Just visible through the trees is a tremendous bronze eagle on a sandstone pedestal, its wings swept back as if about to take flight.

This is the memorial no one in Kiel likes to talk about. Built in 1930 to commemorate the 5,000 German submariners killed in the First World War, its purpose soon grew as thousands of Germans met their ends in the cold waters of the North Atlantic during the Second World War.

A wall below the bronze eagle is lined with plaques dedicated to lost subs. Each is engraved with the names of the captain and crew, and where and how the sub sank. The plaques chart the course of the war: after 1942, the dates crowd together, nearly every marker reading “American torpedo plane” or “American destroyer.” In all, there are more than 700 U-boats listed, and the names of 30,003 men are carved on the memorial’s curved walls, a reminder that three out of four men who served on German U-boats perished.

For locals, the Möltenort submarine memorial is also an uncomfortable reminder of Kiel’s contribution to the German war effort. It’s not marked on the map I bought at the train station, or listed among Kiel’s tourist sites. When I lived here, people would eagerly direct me to Kiel’s many beaches and local museums. But when I asked about the U-boat memorial their smiles faded. “That’s not very interesting for tourists,” one woman told me. “It’s small and hard to find. I wouldn’t bother.”

Just a few ferry stops farther is a memorial with a different spin. In Laboe, a popular resort at the mouth of Kiel’s fjord, I headed for the tallest thing on the horizon: the 278-foot Marine-Ehrenmal, or Naval Monument, a stark, concrete-and-brick tower dedicated to lost sailors from all the world’s navies. A small, newly renovated museum in the base of the tower tells the story of the German navy, and an observation platform at the top offers sweeping views of the fjord and Baltic.

This monument, too, has a clouded history, as I discover when I meet with museum director Adalbert Rohde. By coincidence, I’m here on a sensitive day. Exactly 75 years before, Rohde tells me, Adolf Hitler himself presided over the tower’s opening ceremony. “We’re not making a big deal out of it—we’d rather not talk about it at all,” Rohde says quickly. “We don’t want to be associated with the Nazis in any way.” Rohde assures me Hitler hated the memorial. The führer deemed it “an unparalleled piece of kitsch,” and never went back.

At the base of the memorial is a museum of a different sort: a 220-foot-long metal tube that was once part of the German navy’s feared Wolf Pack. U-995 is a dry-docked U-boat, one of the few not sunk during the war or scuttled at war’s end. Built in 1943, the craft was in Norway for repairs when Germany surrendered. It served as a training vessel for Norwegian sailors for decades, before it was given back to Germany in the early 1970s. Today the U-995 Technical Museum is one of Kiel’s most popular attractions.

I join a handful of tourists filing through the narrow ship, crowding into the command center and lining up at the tiny hatch leading to the torpedo room—which doubled as sleeping quarters for 25 men. Valves and handles and pipes protrude from walls and ceilings, forcing me to hunch nearly double to protect my head. The other visitors make their way out, and for a few minutes I have the ship to myself. In the command room, I stand by the periscope and imagine the tension on board as the wolf snuck up on its prey.

For more than half a century, these memorials were the sole formal reminders of Kiel’s war experience. But over the last decade, a group of local citizens has worked to highlight the price Kiel paid for its role as a U-boat harbor. On a hill overlooking Kiel, a hulking concrete bunker is slowly being turned into a museum to remind visitors of the war’s toll on the city.

Because of its strategic importance to the war effort, Kiel was one of the most heavily bombed cities in Europe; it was attacked 90 times. And because Kiel lay along the flight path to major targets like Hamburg and Berlin, its air raid sirens sounded over 600 times during the last three years of the war, sending people scurrying at least once a week, often more, for the 130-plus bunkers dotting the city.

Kiel was no soft target. The city was heavily fortified with antiaircraft guns and barrage balloons. Massive smoke pots were lit along the wharves in an effort to conceal the harbor and the town. But navy personnel and their families, along with workers in the city’s U-boat factories and tens of thousands of forced laborers from Russia, Poland, and elsewhere in occupied Europe, were still trapped in the crosshairs of Allied bombers.

In 1995, a group came together to preserve the Kilian bunker, a fortified pen that once sheltered U-boats. The concrete structure was dynamited after the war, and its shattered ruins lay in the town’s fjord for decades. “We wanted to preserve them as visible evidence of the fate of the city,” volunteer Stephanie Brix says. In the end, town officials went ahead with plans to remove the broken bunker from the fjord, eliminating the last of the city’s sub pens. But the group—which calls itself the Kilian Mahnmal, or Kilian Memorial—had enough momentum to acquire another abandoned bunker and turn it into a museum in the five years since I lived here.

Dubbed the Flanders bunker, it was designed to hold 750 adults, but often fit three or four times that many inside. At the end of the war, British sappers blew holes in the sides, making it useless.

Today, the holes have been turned into windows, and visitors can walk through the three-story bunker and get a sense of the original floorplan—and the cramped conditions people endured. On the top floor was a command center; lower floors included a room set aside for the families of naval officers and a room reserved for U-boat crews. Other displays include dud Allied bombs recovered from the surrounding area. In addition to turning the bunker into a museum, the Kilian group has collected oral histories from people who survived the war in Kiel. Their testimonies have been turned into displays that hang on the bunker’s bleak walls.

Brix says the grassroots project’s goal is to explore and expose a dual truth that might have been difficult for people here to accept just a decade ago. The people of Kiel—like people all over Germany—suffered tremendously at the hands of Allied bomber crews. But the city was hardly an innocent victim. “The city was bombed because these war machines were built in Kiel,” Brix says. “We didn’t want people to forget that.”

Andrew Curry is a journalist based in Berlin, covering culture and science for a variety of magazines. He came to Germany in 2005 on a Fulbright Fellowship, and studied German in Kiel before moving to Berlin.

When You Go

Kiel is about 55 miles northeast of Hamburg. From Hamburg’s main train station, regional trains leave every hour for Kiel. If you’re spending the night, the Atlantic Hotel at Raiffeisenstrasse 2 is higher-end, conveniently situated downtown; the Nordic Hotel at Holstenplatz 1-2 is also centrally located and reasonably priced.

Where to Stay and Eat

A walk along the waterfront takes you by a number of cafés and restaurants; LOUF, right next to the Reventloubrücke ferry stop, is a great place to grab a beer and watch boats sail up the fjord. Laboe, where the Naval Monument and U-boat museum are located, has a number of restaurants crowded around the ferry dock. For great harbor views and northern German dishes (heavy on fish), try Restaurant Baltic Bay at Fördewanderweg 2.

What Else to See

While typically beautiful between June and mid-September, the weather can be quite wet and cold the rest of the year. The high point of Kiel’s calendar is the Kieler Woche in the last week of June, an international sailing and music festival that draws thousands of sailboats from around the world—and nearly three million tourists. Book very early or avoid that week if you’re not a sailing buff.

The volunteer-run Flanders bunker is often closed, especially in the winter. It’s a good idea to contact the Kilian Memorial Foundation ahead of time (mahnmalkilian.de/kontakte.html). Tours in English can be arranged in advance.