At the close of the Battle of the Atlantic a long-range German U-boat played a deadly cat and mouse with American warships and aircraft.

A few minutes after noon on April 23, 1945, USS PE-56, a World War I–era Eagle-class patrol craft, came to a dead stop in the Gulf of Maine a few miles off Cape Elizabeth. Commissioned in 1919, the 200-foot-9-inch ship had distinguished itself earlier in World War II by rescuing survivors from USS Jacob Jones, a destroyer sunk by a German submarine off Cape May, N.J., in February 1942. But by 1945 the old tub, slow and never very seaworthy, had been reduced to towing a green cylindrical buoy nicknamed “the pickle” and used as a practice target by land-based Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers out of Naval Air Station Brunswick.

The aged vessel still carried a 4-inch gun, a 3-inch weapon and three .50-caliber machine guns, but with the war in Europe nearing an end, the U.S. coastal waters were considered far less perilous than they had been two or three years earlier—a time when Adolf Hitler’s U-boats ranged up and down the Eastern Seaboard sinking merchant and naval vessels alike. But for an unspecified problem that had apparently prompted the ship’s commander, Lieutenant James G. Early, to bring PE-56 to a halt that afternoon, the training voyage had been entirely normal, and the 62 crewmen had relaxed to the point of near boredom.

That all changed about 15 minutes after noon, when a tremendous explosion broke the patrol boat’s back. Five officers—including skipper Early—were killed outright or knocked unconscious by the detonation and went down with the rapidly sinking vessel. The sole surviving officer, Lt. j.g. John Scagnelli, a former competitive swimmer at New York University, staggered to the rail and jumped for it. Some two dozen sailors also made it into the 40-degree water, though several soon succumbed to shock or hypothermia as Scagnelli and the hardier sailors struggled to survive. By the time the destroyer USS Selfridge reached the scene some 20 minutes after the explosion, rescuers were only able to pull Scagnelli and 12 enlisted men from the sea alive; 49 others had perished.

Nine days after the sinking a Navy Court of Inquiry ruled the explosion that sank PE-56 and led to the deaths of most of its crew was the result of a boiler explosion. The true agent of the vessel’s destruction was something far less random and infinitely more lethal—and less than two weeks later it would claim another victim.

Late on the afternoon of May 5 the 369-foot, 5,353-ton collier SS Black Point—loaded with more than 7,000 tons of coal destined for the Edison Power Plant in South Boston—was sailing northward past Point Judith, Rhode Island. The route was considered so safe that the vessel’s master, Captain Charles E. Prior, had posted minimal lookouts, though five U.S. Navy Armed Guards were aboard to man the ship’s main deck gun. Black Point was passing in sight of the Coast Guard lookout at Point Judith Light at 5:40 p.m. when a massive explosion sundered the aft 50 feet from the vessel. The doomed collier immediately started to settle by the stern and list to one side as sailors scrambled to abandon ship through the blacked-out interior. From deep inside the wreckage crewmen could hear the terrified screams of the ship’s mascot, a pet chimpanzee. Black Point’s radio operator got off a distress signal, but the collier slipped beneath the waves within 15 minutes. While the majority of the 41-man crew survived, 11 merchant seamen and a member of the Navy gun crew died.

PE-56 and Black Point were just two among the thousands of vessels lost during World War II, yet they hold a dubious distinction—they were the last American warship and last merchant vessel, respectively, sunk by direct enemy action during the Battle of the Atlantic. Contrary to the Navy’s findings, PE-56 had not succumbed to a boiler explosion—a torpedo had struck the patrol craft. The same was true for Black Point, which went to the bottom one day after Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander in chief of the German Kriegsmarine, had issued a cease-fire order to all U-boats. And, as it turned out, both American ships had been targeted by the same man: 24-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Helmut Frömsdorf of U-853.

Why would the young officer carry out such attacks when the war was so obviously over, and—in the case of Black Point—in direct contravention of his orders? Frömsdorf was never able to answer those questions, however, for in one of those ironies so common in war U-853 was the second to last German submarine sunk in combat in World War II.

Helmut Frömsdorf was born far from the sea, in Schimmelwitz, Silesia, on March 26, 1921. At that time the region’s people—40 percent ethnic German and 60 percent ethnic Polish—were engaged in a tumultuous plebiscite to decide whether Silesia would remain part of Germany’s Weimar Republic or join the reconstituted nation of Poland. The plebiscite, held the same month Frömsdorf was born, reversed the demographics: 60 percent of Silesians voted to stay German, and 40 percent voted to join Poland. The decision sparked years of fierce fighting between Polish irregulars and German Freikorps volunteers.

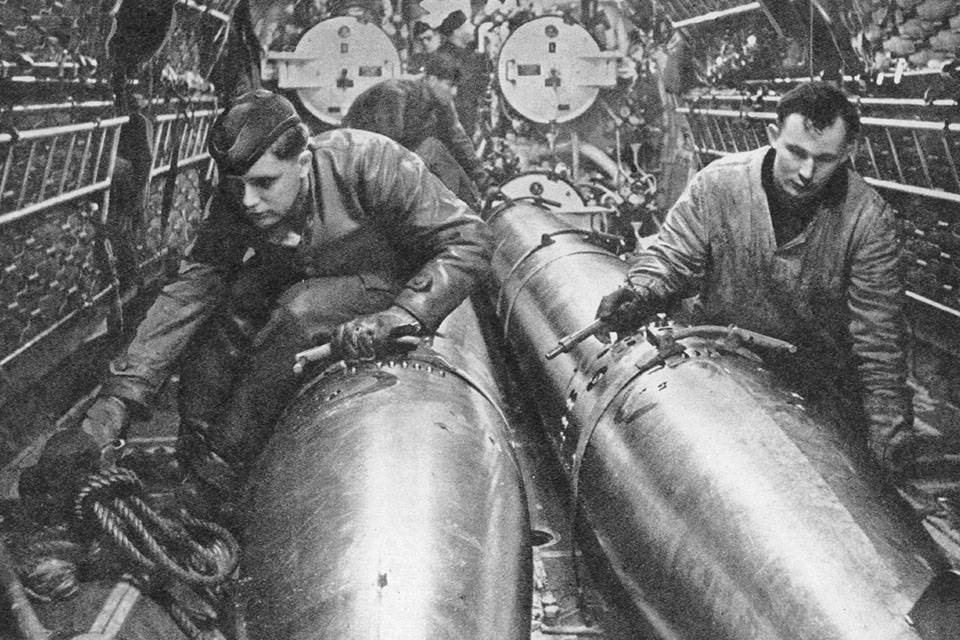

Frömsdorf’s family was solidly in the German camp, and he became an officer candidate in the Kriegsmarine on Sept. 16, 1939, two weeks after Hitler ordered the invasion of western Poland and the day before Soviet forces moved into the eastern part of the country. The young naval officer advanced steadily in rank, and by October 1943 he was an Oberleutnant zur See (equivalent to a U.S. Navy lieutenant, junior grade). Frömsdorf wanted to serve in submarines, but he faced one formidable obstacle—his own lofty stature. At 6 feet 5 inches he was far too tall for the cramped conditions aboard U-boats. But by 1944 attrition throughout the navy’s ranks had made such restrictions immaterial, and the tall young officer finally won assignment to a submarine, Lieutenant Helmut Sommer’s U-853. The vessel, a long-range Type IXC/40 submarine, was initially assigned to weather patrols in the mid-Atlantic. In honor of Sommer’s ability to elude enemy warships, its crew nicknamed the sub “Der Seiltänzer” (“Tightrope Walker”).

Though not directly engaged in the fight against Allied shipping, the submarine did not escape combat. On May 25, 1944, while surfaced in proximity to the liner turned troopship RMS Queen Mary, it came under rocket attack from three carrier-based Royal Navy Fairey Swordfish but managed to escape unscathed after engaging the attackers with its anti-aircraft guns. Things did not go as well for U-853 three weeks later, however, when targeted by a hunter-killer group comprising the escort carrier USS Croatan and six destroyers. The American ships stalked the submarine for three days, and Croatan’s aircraft pounced when the German vessel surfaced to transmit weather reports and recharge its batteries. U-853’s gunners again fought back, but strafing fighters killed two sailors and injured several others—among them Captain Sommer, who sustained 28 wounds from bullet fragments or shrapnel and ordered the boat to dive before collapsing. Sommer survived but was invalided home on U-853’s return to base at Lorient.

The submarine was supposed to undergo repairs at the French port, but Allied forces had advanced so quickly after the recent D-Day landings in Normandy that U-853 was ordered back to Germany for the necessary work. Frömsdorf served as acting commander during the tense and dangerous voyage to Kiel, where over the following months repair crews returned the sub to a state of combat readiness. After an uneventful seven-week patrol in the Western Approaches of the British Isles, the sub headed north to the U-boat pens at Flensburg, Germany, for further upgrades. As part of the process workmen fitted the sub with a retractable air-intake and exhaust snorkel that enabled U-853 to run its diesel engines while submerged—an ability that might well have prevented both summer attacks.

One other significant change occurred while U-853 was in port—on September 1 Helmut Frömsdorf assumed formal command. Though never a member of the Nazi Party, he was dedicated officer, and his new assignment filled him with both pride and foreboding. “I am lucky in these difficult days of my Fatherland to have the honor of commanding this submarine, and it is my duty to accept,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. “I’m not very good at last words, so goodbye for now, and give my sister my love.”

When U-853 again headed to sea in late February 1945, the sub and its young captain had a new mission—instead of tracking the weather, they were to cross the Atlantic and harass shipping off the East Coast. The crossing was slow and tense, as the U-boat often ran submerged to avoid being spotted by enemy warships and aircraft. It remained undetected, however, and Frömsdorf celebrated his 24th birthday a few weeks before the submarine arrived on station.

Pickings were slim until April 23, when the young officer spotted smoke on the horizon and submerged to close in for a better look. Peering through the sub’s periscope, he found himself looking at PE-56, apparently dead in the water. The surface ship’s shape, color and weapons marked it as a warship, and Frömsdorf lost no time in launching a torpedo. The fish ran hot and true over the 600 yards between hunter and quarry, and within seconds it slammed into the stationary patrol boat. The resulting explosion sent a geyser of water 200 feet in the air and lifted PE-56 from the water in two pieces. Certain the enemy vessel was doomed, Frömsdorf briefly surfaced, then ordered an abrupt course change and took the sub back down. Within minutes of the attack the destroyer Selfridge arrived, picked up survivors and began an intense sonar search that picked up a single, fleeting contact, but U-853 escaped into deeper water and later evaded a sonar-directed attack by the frigate USS Muskegon.

Days later Frömsdorf sighted and sank Black Point, but this time he was unable to slip the enemy noose. Even as the collier settled to the bottom, the Yugoslav-flagged freighter Kamen arrived on scene and—at considerable risk to itself—heaved to in order to pick up survivors. Its radio officer also transmitted an SOS reporting the attack. Within two hours a three-ship U.S. Navy hunter-killer group arrived off Point Judith. The destroyer escorts Atherton and Amick and frigate Moberly immediately began a coordinated sweep for the U-boat, which the veteran American commanders assumed would try to elude sonar contact amid East Ground, a steep shoal some 12 miles to the south.

Although U-853 had descended below 100 feet and was running slow and silent, a sonar operator aboard Atherton detected the sub, and the sea hawks swooped down on their prey. Over the next 16 hours the American vessels dropped some 200 depth charges and launched repeated salvos of hedgehogs—forward-firing mortar projectiles. During the night the destroyer Ericsson joined the party, and while Amick had to break off contact, seven other warships formed a cordon around the search zone. By daybreak on May 6 two Navy anti-submarine blimps had arrived over the target area, dropping sonar buoys and smoke and dye markers atop U-853’s presumed position. The U-boat made repeated attempts to escape, but the all-hearing sonar inevitably reacquired it. After launching another salvo of hedgehogs, Atherton noted drifting oil slicks and debris. Within minutes sonar operators aboard both blimps reported sounds they described as “rhythmic hammering on a metal surface, which was interrupted periodically,” followed by “a long shrill shriek, and then the hammering noise was lost in the engine noise of the attacking surface ships.” As the explosion-roiled water calmed, a Kriegs-marine officer’s black cap floated to the surface.

Despite the wealth of wartime records and all that is known about the sinkings of PE-56, Black Point and U-853, several nagging questions remain regarding the loss of the three ships.

The first—why Frömsdorf would endanger his ship and crew to sink the obsolete and decidedly nonthreatening PE-56—is perhaps the easiest to answer. Relatively harmless as the patrol boat may have been, it was a legitimate target. German forces were still fighting to defend Berlin and Dresden against the advancing Soviets when Frömsdorf launched the lethal torpedo that sank the American vessel on April 23. But two questions about the attack on PE-56 persist. Why, against naval regulations, had commander Early brought his patrol ship to a dead stop in a war zone, especially in the face of warnings from U.S. intelligence that U-boats remained operational and that Kriegsmarine commander in chief Dönitz was still calling for all-out resistance? And why had a Naval Court of Inquiry attributed PE-56’s demise to a boiler explosion, though several survivors reported having seen a U-boat and even described the red-and-yellow shield painted on U-853’s conning tower? We will never know the answer to the first question, given that Early was among those killed in the attack. And while it seems likely the Navy mischaracterized the nature of the sinking in order to play down the lingering U-boat threat, that answer will likely remain hypothetical, as supporting evidence has yet to surface.

Turning to the sinking of U-853, we are faced with another nagging question.

On May 4 Grand Admiral Dönitz—who had become titular president of Germany after Hitler’s April 30 suicide—ordered his U-boat fleet to cease hostilities against Allied shipping, yet Frömsdorf sank Black Point the next day. The most likely reason, of course, is that he simply hadn’t received Dönitz’s order—to elude Allied ships and aircraft, U-853 often remained submerged and could have missed the message from Germany. But there are other possibilities. The young U-boat captain may have been grieving the loss of his Silesian homeland—overrun by vengeful Soviet and Polish forces as the war in Europe drew to an end. Or perhaps he was ambitious for a medal—though his score of just two ships sunk for a combined total of only 5,968 tons certainly wouldn’t have vaulted him into the rarified company of Germany’s recognized submarine aces.

Whatever Frömsdorf’s reasons might have been for his actions off the Eastern Seaboard, he killed 61 Americans and was indirectly responsible for the deaths of himself and the 54 other members of his crew—all in the closing days of a war whose outcome had long been foretold. None of the deaths served any practical purpose for either side.

Though inextricably linked to the history of World War II in Europe, the stories of PE-56 and U-853 did not end in 1945.

With regard to the American patrol craft, despite the Navy’s ruling its loss had resulted from a boiler explosion, naval officials—as well as survivors and relatives of those killed—continued to push for a broader investigation into the event. In 2000 naval historian and attorney Paul Lawton joined forces with Bernard Cavalcante of the U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command and German historian Jürgen Rohwer to review the facts surrounding the sinking. They concluded a torpedo fired by U-853 had sunk PE-56, and a year later the Navy reclassified the ship’s sinking as a combat loss. At a subsequent ceremony the service presented Purple Hearts to the three survivors still alive at the time and to the families of those who had perished in the sinking.

As for U-853, on the very day of its destruction Navy hard hat diver Edwin Bockelman, from the submarine rescue ship USS Penguin, descended to the wreck. He found the U-boat in 139 feet of water, its hull badly damaged and its conning tower hatch crammed with the bodies of crewmen wearing escape gear. After noting the number painted on the tower, he brought one sailor’s body to the surface as evidence of the kill. Another body was later found floating off the Rhode Island coast—both eventually received formal burials. Some years later a recreational diver thoughtlessly recovered a skeleton from the wreck, prompting protests from the German government, as the sunken U-853 qualifies as a war grave under international maritime law.

Sadly, that status has not prevented other looters from bringing up countless artifacts from U-853, which remains a popular—if somewhat hazardous—destination for recreational divers.

John Koster is a frequent contributor to HistoryNet magazines and the author of Operation Snow (2012). For further reading he recommends Due to Enemy Action, by Stephen Puleo.