In 1910 an eccentric newspaperman, his crew and a cat set out from Atlantic City in a dirigible, aiming to make the first transatlantic crossing by air.

W alter Wellman is hardly a household name today, but he made a significant contribution to aviation in the early 20th century. A successful Midwestern newspaper editor, Wellman longed for adventure, a predilection that led him to mount five expeditions to reach the North Pole before his ultimate venture, the first attempt to cross the Atlantic in an airship. Although all his expeditions ended in failure, Wellman’s contemporaries saw him as a visionary, and celebrated his daring in the opening chapter of American aviation.

Born in Mentor, Ohio, on November 3, 1858, Wellman was ambitious from an early age, founding a weekly newspaper in Sutton, Neb., at age 14. Seven years later he started the Cincinnati Evening Post. He later spent several years working as the Washington, D.C., correspondent for the Chicago Herald, becoming president of the Washington Press Club.

The eccentric newspaperman first came to national attention in 1892, when he claimed to have identified the exact spot where Christopher Columbus had landed on San Salvador. He even built a memorial at that location.

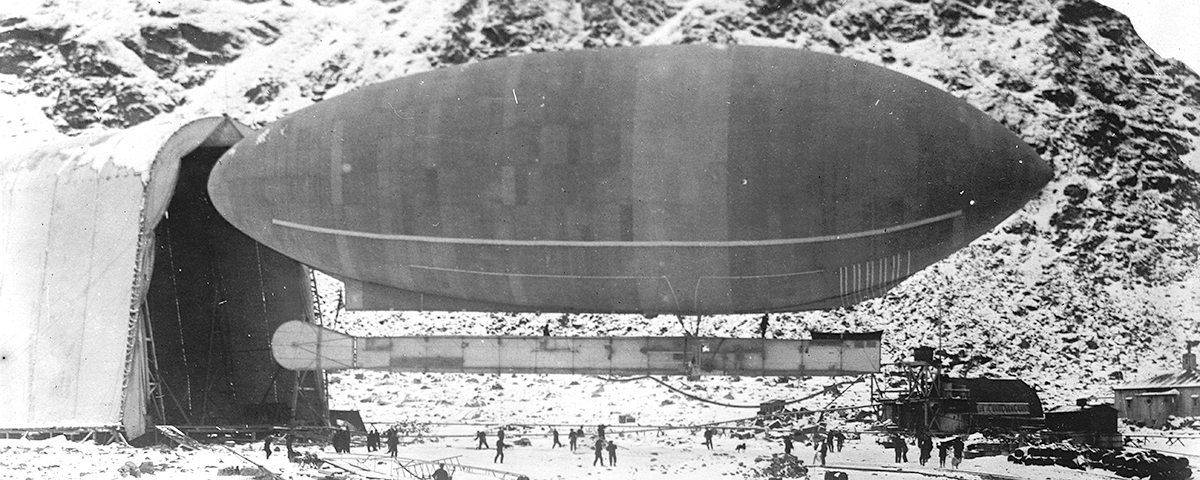

Wellman launched an unsuccessful attempt to reach the North Pole by dogsled in 1894, then tried again in 1898 and 1899, falling short each time. After deciding the easiest way to reach his goal would be to float above all that treacherous ice and snow, he raised funds for the construction of an airship in France. Wellman made two pole attempts in the dirigible, dubbed America, in 1907 and 1909. The first trip ended prematurely when he ran into a snow and ice storm that forced a hasty landing a few miles into the voyage. On his second attempt he had traveled 33 miles when a leather tube filled with ballast broke, causing the airship to rapidly gain altitude. According to the Lincoln Evening News, “By skillful maneuvering, Wellman succeeded in landing without injury of the crew, though the America was badly damaged.” While Wellman was planning yet another attempt, he learned that Robert Peary and Frederick Cook had both already claimed to have reached the pole.

Wellman next set his sights on making the first transatlantic voyage by air, a venture financed by The New York Times, the Chicago Record-Herald and the London Daily Telegraph. He agreed to sell his story to those papers for what was reportedly “a fabulous sum.”

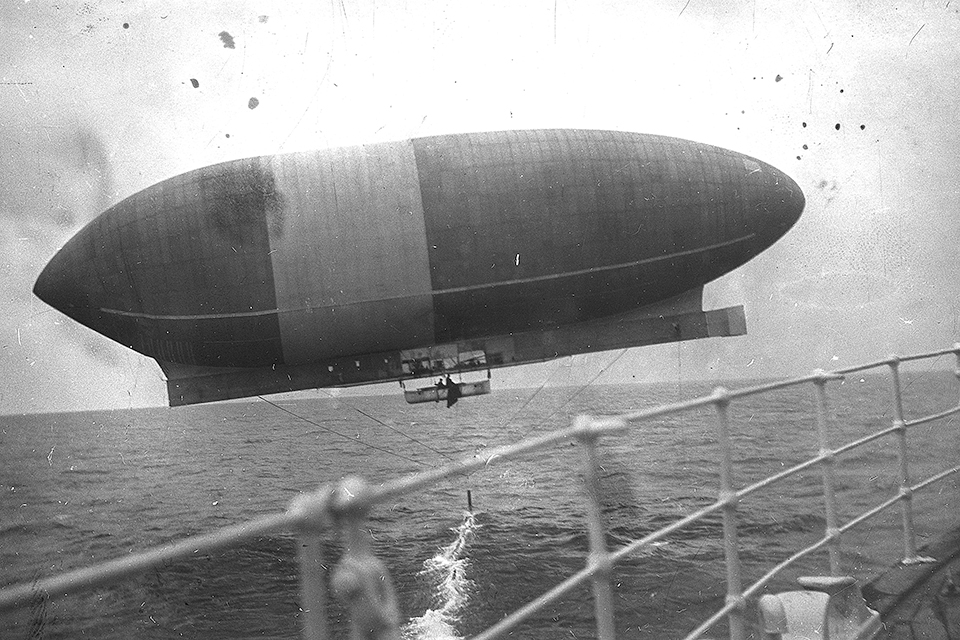

The newly expanded and improved America was 228 feet long, 52 feet at its greatest diameter and could hold 345,900 cubic feet of hydrogen gas. The New York Tribune described it as “the nearest thing in shape to a cigar, which aeronautics has produced….The contents were well clothed. The balloon itself was composed of three thicknesses of cotton and silk, gummed together with three layers of rubber, weighing 4,850 pounds.” Two engines, driving fore and aft propellers, enabled the airship to travel at 20 mph. Suspended below the gasbag was a 27-foot covered lifeboat, equipped with a Marconi wireless set and storage compartments for provisions.

Perhaps the strangest component of this massive beast was its “equilibrator,” an experimental stabilizing cable that was supposed to regulate the airship’s upward and downward movement. Invented by Melvin Vaniman, America’s chief engineer, it took the place of a drag rope, such as those used on balloons. As sunlight heated the hydrogen gas during the dirigible’s passage, it was feared the craft would rise uncontrollably. The equilibrator trailed along the water’s surface, serving as an anchor to prevent sudden gains in altitude. Suspended by a motor-driven lifting harness, it was attached to 30 small fuel tanks that supplemented the 1,200 gallons carried aboard the airship. “As the gasoline is required,” reported the Mansfield News, “the steel cable will be pulled up into the car of the balloon and a tank emptied.” This contraption would prove to be a very bad idea.

America’s cabin, or car, was stocked with a gas stove and enough food to feed six men for a month. Storage batteries provided power for electric lights and a telephone system. The airship’s wireless set in the lifeboat was capable of sending messages more than 50 miles, and receiving them from much greater distances. Since Wellman planned to stay within established shipping routes, he hoped to remain in touch with passing vessels, which could relay messages to America and Europe.

Besides Vaniman, an experienced balloonist who had joined Wellman in America during his pole attempts, the airship crew included British pilot and navigator Murray Simon and Australian wireless operator Jack Irwin. Albert Louis Loud and John Aubert served as engineers.

Wellman had been sensationalizing his trip in the press for weeks by the fall of 1910, issuing bulletins that drew curious locals to the Atlantic City, N.J., hangar where America was tethered. By the time the crew was at last ready to launch on Saturday, October 15, many had lost interest, and the crowd had dwindled. Word quickly spread, though, and the “entire resort was aroused when news of the start circulated,” according to the Lincoln Evening News. “Thousands were soon packed on the boardwalk.” The crewmen were all dressed for their adventure in what was described as “khaki aviation costumes.”

For his part, pilot/navigator Simon was glad to finally be getting underway. He thumbed his nose at critics who had anticipated disaster for America and its crew, writing: “We will make those blooming critics eat their own words. They have been hammering us for the last month, ridiculing our ‘worn-out gas-bag,’ and ‘old coffeemill for motor,’ telling us we should never leave sight of land, that the wireless plant we carried is a mere bluff, and that all the men engaged to work the ship have ‘cold feet.’”

As the crew prepared to cast off shortly after 8 a.m., they were joined by a small gray kitten that had made himself at home in the hangar. There are conflicting accounts about how the cat—dubbed Kiddo—ended up aboard the airship. Some said Mrs. Vaniman placed him on board at the last minute. According to another source, the cat was unceremoniously tossed inside the lifeboat as they lifted off, and he proceeded to yowl piteously. A crewman reportedly stuffed the kitten into a sack and tried to lower him to a boat, but it was too late for a safe transfer. Whatever the case, Kiddo joined the crew, and spent much of his time snoozing in a corner of the lifeboat.“In the long days and longer nights that followed,” wireless operator Irwin later wrote, “I will admit I was grateful for that kitten’s affectionate company.”

By the time all was ready for the departure, nearly 100 policemen, firemen and lifeguards were holding onto the ropes to keep the airship from floating away. Wellman shouted to the crowd, “We are going for a trial, and if the going is good, we are going up and over the ocean.” Then the improvised ground crew let go, and with the assistance of a tugboat, the leviathan slowly moved out over the ocean, casting an enormous shadow as it went. “Rising majestically, the America disappeared in the fog almost immediately,” reported the Lincoln Evening News. “Only a tiny motorboat buffeted the breakers and followed in the uncanny shadow cast by this new thing,” another paper reported.

At 1:40 p.m. Wellman reported: “Sea is very smooth. We are not crowding our motors hard. Averaging at 15 knots an hour. All going well.” Several congratulatory messages went out to the dirigible, but as Atlantic City grew more distant and the signals became weaker, Irwin had difficulty hearing them over the engine noise. Complicating matters, he was initially concerned that sparks generated by the wireless equipment might accidentally set the gasbag on fire: “For months we had discussed the possibility of sparking in the rigging [which served as an antenna] and the risk of burning a hole in the fabric of the balloon, so when the moment came to ‘sit’ on the key of the transmitter, I think I can be pardoned for my nervousness. I am sure I experienced the moment that a suicide passes through when he is about to pull the trigger.”

That evening, pilot Simon later recalled: “In the midst of the fog we narrowly escaped a collision with a four-masted schooner which suddenly crept though the fogbank like a gigantic spectre. The people on board the schooner must have been much more alarmed than we were. They undoubtedly could hear our motors, but could not see us.”

Ominously, the crew had been dealing with engine trouble since soon after their launch. As Irwin later wrote: “Due…to the lack of trial flights, the engines required tuning and we proceeded very slowly during the morning of the first day. Several times during that morning either one or the other of the engines had to be stopped, caused by sand in the bearings. Our hangar at Atlantic City was in a most exposed spot where every wind that blew brought clouds of sand.”

Worse still, the equilibrator was not functioning as advertised. According to a newspaper report, the “theoretical equilibrator was not proving practical at all. It was struggling along like a poor relative and straining the big craft in a manner which made Europe seem very far away.” While the dirigible should have been unaffected by rough seas, the equilibrator was making every wave felt in the cabin. “It jerked shockingly at the lines which held it to the America,”said Wellman. “Under this stress the ship set up a rolling motion, which added to the strain and threatened the entire destruction of the craft if long continued.”

“It was a dreadful night for the men aboard the ship,” he continued. “There was much to be done to ease the strain and all did everything possible. At times some would become exhausted and one by one the men would sleep for a time. They went to their hammocks expecting that they would awake to find themselves in the ocean, but all they wanted was to sleep and they did so.”

Wellman later told the Mansfield News: “The trailing tail held the balloon back and at times pulled it down toward the water and we had to ballast the ship at the cost of a loss of gasoline dropping to the waves….The equilibrator, holding us back like a brake, made us throw out the gasoline.” The crew eventually jettisoned most of their supplies and gear, in hopes of staying aloft.

During that first long night, Irwin reported, one of the engines had to be stopped when its propeller began to wobble alarmingly due to a failed bearing. And by the time he sent the distress signal “CQD,” the second engine had failed as well.“Engineers Loud and Aubert commenced to take the large motor apart and throw it overboard, to lighten the ship,” he wrote. From then on, buffeted by a storm, they drifted south on the winds, knowing that they couldn’t possibly make it all the way across the Atlantic.

Simon, the pilot, later described their travails to the Manitoba Press:

On Sunday our wireless apparatus was attracting the lightning, as we were passing through a terrific electrical storm. We lowered the dirigible to within a few feet of the water, but when we desired to raise again, we found it necessary to sacrifice several barrels of gasoline. Monday, the hot sun caused the gas in the bag to expand suddenly and we shot up to a height of 3600 feet. We had hard work getting her down again. From then on we…were forced to sacrifice much gasoline, practically throwing over all the fuel we had. After that there was nothing for us to do but drift and trust to luck. We did not abandon the America until we sighted a ship.

Early on October 18, America’s adventure ended. The liner Trent, having heard Irwin’s distress signal, spotted the dirigible some 450 miles east of Cape Hatteras, N.C. In the Lincoln Daily News, Simon recounted: “Dawn was breaking when we picked up the Trent and she was a most welcome picture in the distance. Her lookout’s eyes were very sharp, as our very first signal was answered and we then signaled her to stand by as we were in need of aid.” The whole crew descended to the lifeboat in preparation for their rescue. Irwin described how that happened in the Lincoln Evening News:

After all hands had dropped into the lifeboat which swung below the America, I jabbed a hole in the gas bag and as the gas escaped we dropped into the ocean. When within a few feet of the water the ropes were cut and the lifeboat dropped just as we had planned. The dirigible, released of the weight, shot skyward. After we were landed on the deck of the Trent we could see what was left of our airship floating off to the westward at a speed of about twenty-five miles an hour.

The rescue was not without suspense. When Trent first came rushing to their aid, the crewmen initially feared the liner would run over the lifeboat. Some of the men even briefly considered jumping overboard. The ship soon slowed down and threw them a line, but rough seas made it difficult for the crewmen to hold onto it. After several attempts, a secure connection was finally established, the crewmen clambered up a ladder and the lifeboat was lifted aboard.

Simon later put a positive spin on their venture, saying: “We sacrificed the airship but we saved our lives, and above all, we have gathered a vast amount of useful knowledge which will help largely in the solution of big problems relating to the navigation of the air. And we also saved the cat!”

Despite the voyage’s failure, Wellman and his crew were viewed as heroes. The Lincoln Evening News reported: “When the Trent docks, Wellman and his companions will be greeted by a half score of theatrical agents, armed with blank contracts for vaudeville appearances, lecture tours and other engagements. Even the mascot cat of the America will not be neglected by the managers.”

Although Wellman began working on plans for a new airship design while they were still aboard Trent, he would never mount another transatlantic attempt. It’s unclear why; financial backing may have been a problem, or perhaps Americans’ newfound fascination with the airplane detracted from dirigibles. Though Wellman gave up on his transatlantic dream, he had in fact made aviation history—as the first captain of an airship to be wrecked at sea. He had also established a world record for a sustained flight, traveling more than 1,000 miles in three days. As S.H. Mathews would enthuse in the Literary Digest in 1919:

No greater feat of daring, no greater nerve displayed, no greater gamble with death was ever made than by Wellman, Vaniman, Irwin, Loud, Simon and Aubert, Americans, on October 15, 1910, when they hopped off from Atlantic City, New Jersey in the dirigible airship America in an earnest effort to cross the Atlantic….[T]hey established a record of 1008 miles in 71½ hours (37 hours aloft being the former record of a Zeppelin). When we consider that Wellman’s attempt to cross the Atlantic was made nine years ago… when the non-stop airplane record was at five hours; and further consider, that the air navigators of today have the advantage of a world of knowledge gained from war experience and the progress of science and invention…we are inclined to the belief that Wellman and the brave crew of the America deserve greater credit for the display of nerve of the pure and unadulterated kind.

Even Kiddo, the unwilling participant in a high-flying “feat of daring,” gained a measure of fame, thanks to all the publicity photographs he appeared in with the crewmen. Renamed Trent, after the ship that had rescued him and his companions, he was for a time loaned out to Gimbels department store in New York City, where he was placed in a golden cage that occupied a store window. There he lounged on a luxurious bed, admired by passersby. He subsequently went home with Wellman, becoming his daughter’s pet.

Less than two years later Melvin Vaniman, along with four crewmen, would be killed in an airship just off New Jersey’s coast. On July 2, 1912, he was aboard the dirigible Akron when its hydrogen gasbag exploded 500 feet above the waves near Atlantic City. For many years it was believed that Akron’s lifeboat—the same one used during America’s voyage—had been lost. But in 2010 the Goodyear Corporation, which had recovered the English-built boat and put it in storage, donated it to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. It’s currently in storage, but Senior Curator Tom Crouch anticipates that it will be put on display once it’s been spruced up a bit. Interviewed for a Smithsonian blog, Crouch said of the boat: “It played an important role in two really interesting flight attempts. It reminds us of those early dreams of flying the Atlantic.”

Walter Wellman, a newspaperman who had repeatedly risked his life in an age of exploration and technical innovation, promptly penned an account of the expedition, The Aerial Age: A Thousand Miles by Airship Over the Atlantic Ocean, which was published in 1911. When he died of cancer at 75 on January 31, 1934, Wellman’s obituary gave his ill-fated expeditions top billing over all the work he had done as journalist. Perhaps he would have wanted it that way.

Kimberly Kenney writes from Canton, Ohio. She is the curator of the McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, and the author of Canton’s Pioneers in Flight, among other publications. Additional reading: The Aerial Age: A Thousand Miles by Airship Over the Atlantic Ocean, by Walter Wellman; and Lighter Than Air: An Illustrated History of Balloons and Airships, by Tom D. Crouch.

Originally published in the July 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.