The Army promises to make you “Be All You Can Be.” The Air Force “Aims High.” The Navy is “Always Courageous.”

But can any of the other branches promise to make you a king? The Marines Corps can.

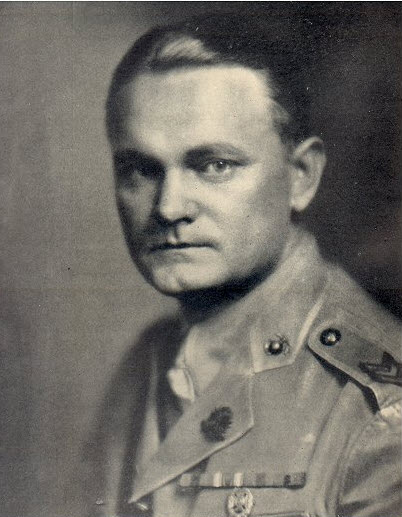

In a stranger than fiction, yet historically true turn of events, one stocky, blonde haired, blue-eyed Marine from a small coal mining town in Pennsylvania went from Warrant Officer to king of the island of La Gonave, Haiti.

Sgt. Faustin Wirkus’ ascent from a poor “breaker boy” — separating coal from slate — to king, is the stuff of Marine Corps legend.

“I had to go to work in the collieries,” Wirkus later wrote. “There was no escaping the sequence of that rule… but there was a different idea in my mind… In the little time I had been in school, it had become foggily known to me that somewhere out beyond the dust, the rattling collieries, and the grimy shacks of Dupont [Pennsylvania], was a world full of thrill and the glory of being alive.”

For Wikus, the path to that thrill and glory lay in becoming a U.S. Marine, and by age 18 the teen ran away from home to become one of “The Few.”

In 1915 he was among the first outfits of “Leathernecks” sent to Haiti to restore order, according to his New York Times obituary.

It was during his first tour that he fell in love with the island, returning for duty on and off for several years before, in 1920, Wirkus made a fortuitous friendship while serving at the tiny outpost of Anse à Gallet.

According to a 1931 Time article, Wirkus witnessed a tax collector arrest a Haitian woman for “voodoo offenses.”

The woman, according to the magazine, claimed that she was Queen Ti Memenne of La Gonave. Although initially transferred to Port-au-Prince to stand trial, the queen was eventually freed due to Wirkus’ pleas for leniency.

Five years later, the Haitian-obsessed Wirkus once again applied for duty on the island. His superiors, according to the Marine, “thought of La Gonave as the butt-end of the world,” yet acquiesced to his request.

Made resident commander of La Gonave, Wirkus returned to the island in April 1925. “During his tenure, he saved the Haitian government thousands of dollars by exposing graft in tax collection and ensured the island farmers were given fair tax assessments. He also oversaw the construction of the first airfield and directed the first census,” according to the USMC.

His practical reforms quickly endeared him to the 12,000 inhabitants of La Gonave, but that endearment went one step further. According to local superstition, “a previous ruler of the island had borne that name {King Faustin I] and, according to legend had vanished in 1848 with the promise that his descendant of the same name would return to take his throne,” wrote The New York Times.

By candlelight on the evening of July 18, 1926, Queen Ti Memenne crowned the gunnery sergeant Faustin II, the “White King of La Gonave.” Carried from the houmfort, or voodoo temple, a blood sacrifice was made via a rooster (The New York Times contradicts this and claims it was a goat), as the crowd shouted “The King! Long live King Faustin!” to the more than slightly confused Marine.

“They made me a sort of king in a ceremony I thought was just a celebration of some kind. I learned later they thought I was the reincarnation of a former king of the island who had taken the name of Faustin I when he came into power. The coincidence was just good luck for me,” the flabbergasted Marine recalled.

Wirkus reigned for an incredible three years while still serving in the USMC, before being recalled to Port-au-Prince after Haitian officials expressed “jealousy” over Wirkus’ successes.

By 1931, King Faustin II was no more, with Wirkus leaving the service and returning stateside. In 1939, he re-enlisted with the Marines, serving first as a recruiter in New York before being transferred to the Navy Pre-Flight School in North Carolina.

The Marine and one-time king died in October 1945, leaving behind a wife and a young son — also by the name of Faustin.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.