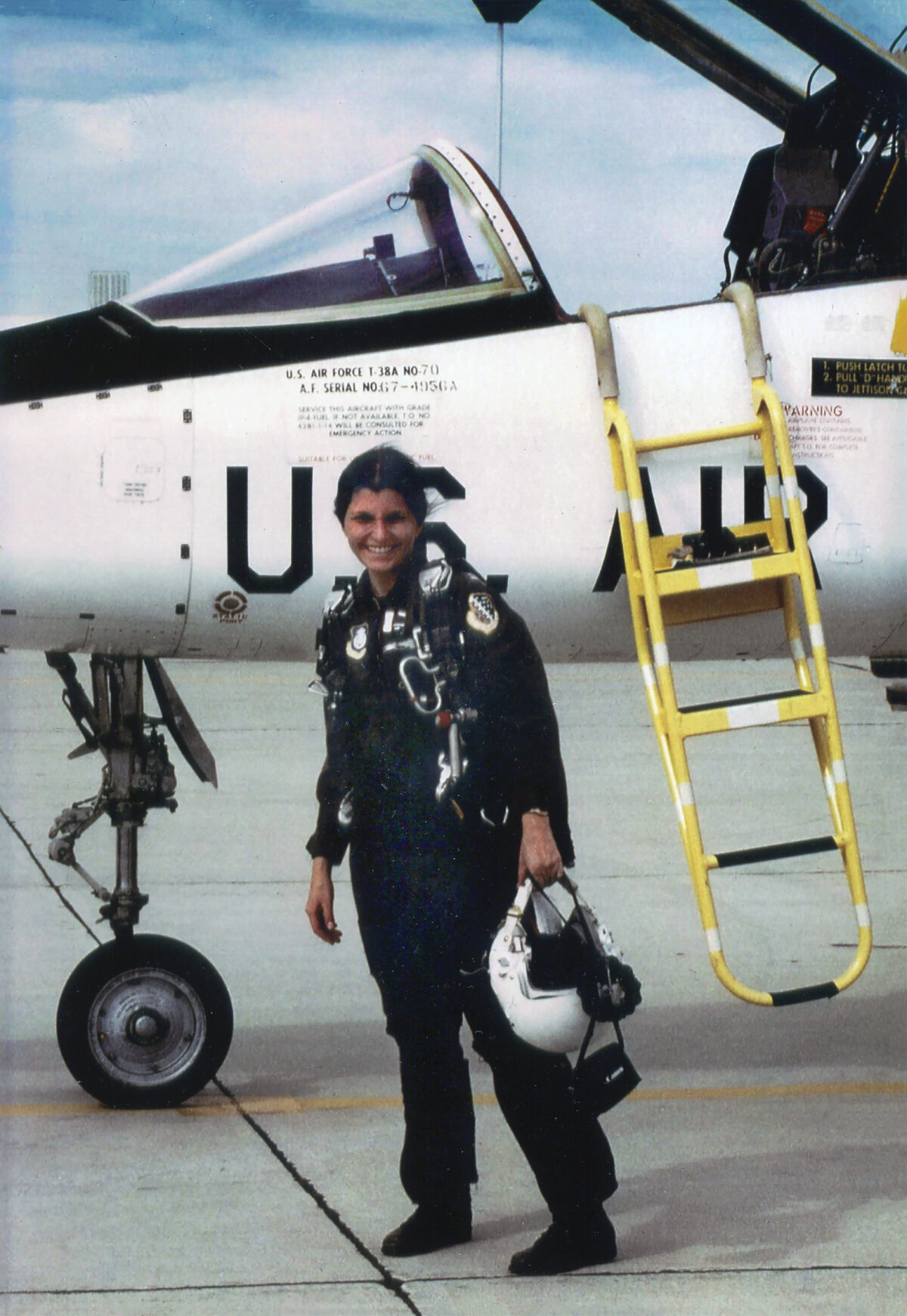

In 1981, Captain Carmen Lucci appeared to have an unlimited future in the U.S. Air Force. The Ohio native had earned a full scholarship as Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s first female AFROTC cadet, and in 1975 she had received her Air Force commission as a distinguished graduate. Her next stop was the University of Tennessee Space Institute, where she earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. In 1977, she entered Air Force active duty.

Lucci had her sights set on being an astronaut, so during her first assignment at Los Angeles Air Force Station, she applied to attend pilot training and the flight test engineering course at the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School (TPS). Accepted to both, she turned down pilot training to attend TPS and arrived at Edwards Air Force Base in June 1980. She was the fourth woman to attend Air Force TPS; all the others had also been engineers, since the Air Force had just recently begun to train women pilots.

One of Lucci’s TPS classmates, fighter pilot Carl Meade, arrived at Edwards a few days before the class started and checked into the visiting officers’ quarters. The clerk on duty commented, “One of your classmates is already here. And she’s quite a pistol.”

Meade thought, “She? A pistol?”

About 30 minutes later, he received a message from the pistol: “I’m Carmen. Let’s go to dinner.”

The two became fast friends, occupying quarters near each other and studying frequently together with two other classmates. They had hectic schedules, with student flights during the mornings and academics in the afternoons. Evenings and weekends were for analyzing data, writing reports and endless reading and homework to learn the theoretical underpinnings of everything from aircraft climb performance to out-of-control spins.

Lucci loved to fly. During test missions with her in the backseat of a McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom, classmate Ted Wierzbanowski remembered that they often had a little free time after collecting the test points they needed for the day. As they flew back to Edwards, Lucci often prodded him for a little extra excitement by saying, “Teddy, do me another Immelmann!” Bob Hood recalled how much fun he and Lucci had on their last flight together as they flew a low-level route in a Northrop T-38 Talon over the desert terrain north of Edwards. However, when Lucci wasn’t zipping through maneuvers in a jet, her lifestyle was more low-key. She cooked, played backgammon and regularly stole cookies from the lunch that Meade packed for himself every day. In 1979 she had married Air Force Captain Thomas Humes.

On March 3, 1981, Lucci was scheduled to fly an early mission with classmate D.J. Halladay, a Canadian Armed Forces captain, in the school’s variable-stability Douglas B-26 Invader. The B-26 had been extensively modified so the flight control system could be altered to make it seem as though it was a different type of aircraft. By repositioning a few dials, the civilian test pilot instructor, Stephen Monagan, could make the B-26 behave like a lumbering B-52, a nimbler C-130, or even an aircraft that didn’t exist, giving students the opportunity to see how different flight control system designs made it easier or harder to fly an airplane. The B-26 was nearing retirement; it was only going to be used for a few more flights and would be replaced by a more modern Learjet.

The three aircrew took off from Edwards about 7:30 a.m. for a local flight of about an hour. After the B-26 failed to return on schedule, Meade—who was supposed to fly the aircraft next—and other TPS personnel called nearby military bases, thinking the crew might have diverted for an emergency. No one had seen the aircraft. Airborne pilots searched near Edwards, thinking the Invader might have landed on a lakebed. Nothing. A formal search party was launched. The students went to their afternoon classes.

About 3:00 p.m., someone entered the classroom with grim news: wreckage from the B-26 had been located. There were no survivors.

The class sat in stunned silence until the instructor dismissed them for the day.

Investigators determined that the left wing had separated from the B-26 during maneuvers at about 8,000 feet.

Meade delivered a eulogy for Lucci at a memorial service a few days later. After the service, a flight of F-4s thundered over the chapel at low altitude to honor the fallen aviators. Inside the chapel, their names were later engraved on a plaque dedicated to test personnel lost in accidents at Edwards.

Three decades later, on March 16, 2012, many of Lucci’s classmates attended a dedication ceremony to name a control room at the test pilot school in honor of her supreme sacrifice. Colonel Noel Zamot, TPS Commandant at the time, said in an Air Force news release: “Tenacity, character, discipline, integrity, confidence, and intellectual curiosity are timeless values and they are what make you successful at the United States Air Force Test Pilot School and in life. Captain Lucci exemplified those values.”

About the same time in 2012, one of aircraft wreck-finder Pat Macha’s teams visited the B-26 crash site. Macha and his teams made several visits to the site over the next few years. During the final visit, a team member noticed a chain in the dirt. When she picked it up, it still held Lucci’s dogtags, badly bent from the severe impact, but otherwise in perfect condition.

Macha’s “Project Remembrance,” which returns personal items located in aircraft wreckage to families, kicked into gear. The Lucci family passed the tags along to her classmates, who mounted them in a shadow box to accompany the small display already outside the control room named for her. On September 20, 2019, Lucci’s classmates assembled once again to dedicate the shadow box and remember a pilot whose promising life had been cut short. “The dedication shows how the flight test community never forgets and also reminds folks that what this community does is risky, but also that those risks are worth the capability we bring to the warfighter,” said Wierzbanowski. “The dedication brought back a lot of good memories and a lot of sadness. It should remind us all that every day is a blessing.”

Carmen Lucci is still the only female flight test engineer to lose her life as a student or graduate of any test pilot school in the world.