Lawmakers announced bipartisan legislation Tuesday that would authorize the president to award a Black veteran of the D-Day landings the Medal of Honor, an initiative that comes after the Army couldn’t move forward in the awards process on its own due to a lack of records.

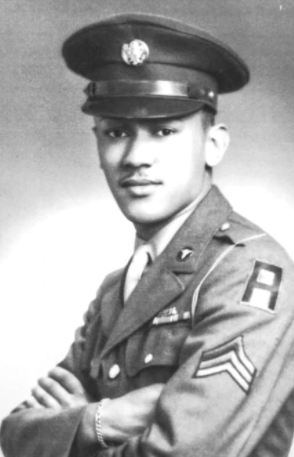

Cpl. Waverly B. Woodson Jr., an Army medic who died in 2005, was originally awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart for his actions on June 6, 1944.

Early on D-Day, Woodson was wounded by shrapnel in his groin and back while still aboard his landing craft as it drove toward Omaha Beach, on the coast of Nazi-occupied France. He spent the next 30 hours removing bullets from fellow soldiers, cleaning wounds and at one point rescuing four men from drowning after their guide rope broke as they were swimming to shore. He only stopped after collapsing from his own wounds on the beachhead.

Woodson’s supporters say a memo unearthed in 2015 indicates he was originally considered for the Medal of Honor, but ultimately did not receive it due to the color of his skin. A fire that destroyed veterans records in 1973 has only complicated the matter.

“One million Black Americans served during World War II — one in every 16 American service members,” Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D–Maryland, told reporters Tuesday. “Of the hundreds of Medals of Honor awarded at that time, not a single one went to a Black service member.”

Van Hollen has been working for years with the veteran’s widow, Joann Woodson, 91, in lobbying for an upgrade. Other lawmakers, including Sen. Pat Toomey, R–Pennsylvania, have since joined the effort.

The new legislation would “give the president of the United States the tool with which he can, with the stroke of a pen, correct this injustice and make sure that Cpl. Waverly Woodson gets the Medal of Honor that he deserves,” Toomey said.

The Army, however, has said that the service lacks the primary source material needed to move forward in the approval process.

“They’re not disputing, to the best of my knowledge, in any way the fact that Cpl. Woodson deserves the medal, but they are claiming that the documentation that supports that decision is not in its proper form,” Van Hollen said.

“But very importantly, we do have this correspondence from one of the commanding officers at the time, recommending Cpl. Woodson for an award to be presented by the president,” Van Hollen added. “The Medal of Honor is that award. We are very frustrated that the Army has not recognized that as evidence here.”

Woodson’s military documents, as well as those of many other veterans, were lost in a 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. The primary source account of Woodson’s actions would have been located there.

What Woodson’s supporters do have as evidence of his actions is a memo uncovered at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and detailed in the 2015 book “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War,” by journalist and photographer Linda Hervieux.

The memo, sent to the Roosevelt White House from War Department aide Philleo Nash, stated that Woodson was first recommended by his commanding officer for a Distinguished Service Cross, which is second only to the Medal of Honor.

But the memo added that Woodson’s actions “merited a Congressional medal,” one that is a “big enough award so that the President can give it personally.” That description would only apply to the Medal of Honor.

In addition to that memo, contemporary press reports documented Woodson’s actions during the D-Day landings. Black newspapers of the time hailed Woodson as the “No. 1 invasion hero,” according to the History Channel. The Army, itself, issued a news release in August 1944 that noted how Woodson “was cited by his commanding officer for extraordinary bravery.”

Woodson’s actions were reviewed in the 1990s, as well, when seven Black veterans were retroactively awarded the Medal of Honor by then-President Bill Clinton. Woodson made the short list to be upgraded, but he was not selected due to the lack of documentation.

This time around, the lawmakers hope their legislation will help circumvent the issue.

Van Hollen and Toomey said they will be working to get the legislation passed in the Senate by unanimous consent. In the House, Maryland Democratic Reps. David Trone and Anthony Brown will be working to do the same.

“I know of no opposition,” Van Hollen said. “You never know what may creep out, but I believe and I’m confident we’ll be able to pull people together on this.”

After being discharged, Woodson went to work at the National Naval Medical Center and the National Institutes of Health for several decades, his widow said.

“He was always dedicated to the medical field,” Joann said. “Not only just the National Institutes of Health, he was also the same way with the community and with family. If anyone was sick or they needed a little bit of a boost or something, he was always there and he was always checking on people.”

Originally published on Military Times, our sister publication.