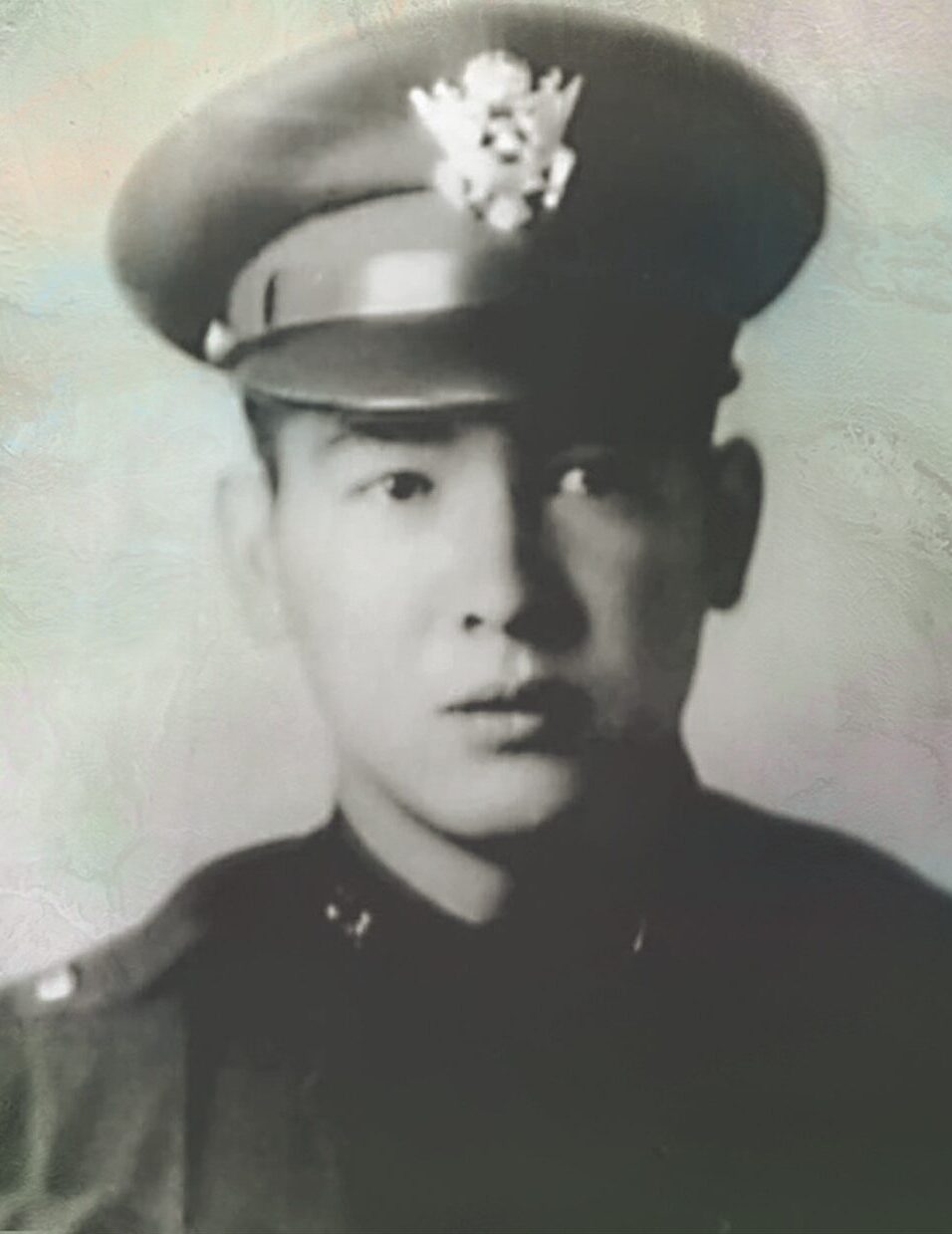

Born in Honolulu, Hawaii, on April 14, 1917, Francis Brown Wai grew up living the American Dream. His father, Kim Wai, had emigrated from China and become a successful banker, while mother Rosina was a native Hawaiian. Educated at Honolulu’s elite Punahou prep school, Francis earned athletic letters in track, football and baseball by the time he graduated in 1935. After two years at California’s Sacramento Junior College, he transferred to UCLA, from which the four-sport athlete graduated in 1940 with a bachelor’s degree in economics.

As war clouds gathered, Wai enlisted in the Hawaii National Guard, which sent him to the U.S. Army’s Officer Candidate School, at Fort Benning, Ga. On Sept. 27, 1941, he was commissioned a second lieutenant—a rare feat for an American of Asian or Pacific Islander ancestry. Assigned as an intelligence officer in Headquarters Company, 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, Capt. Wai was in Oahu when the Japanese attacked on Dec. 7, 1941, and shipped to Australia with the division in 1943.

In April 1944 the division participated in Operation Reckless, the seizure of Hollandia, Papua New Guinea, an Allied victory that eliminated all Japanese forces east of the base. Wai’s reinforced 34th Infantry helped capture Biak Island. Once that springboard was secured in August, the 24th Infantry Division was attached to X Corps for the opening move in Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s promised return to the Philippines—the October 20 landing on Leyte Island.

The 34th Infantry came ashore at Palo, or Red Beach. Landing in the fifth wave, Wai was shocked by what he found. The first four waves of troops were pinned down on the beachhead, leaderless and disorganized due to heavy casualties among their officers. Between them and frontline Japanese defensive positions amid palm groves there was virtually no cover, only an intervening stretch of low-lying rice paddies.

Assuming command of everyone within earshot, Wai, seeing little alternative, led an assault party forward, practically daring the enemy to fire at him. In doing just that, the Japanese gunners gave away their positions, allowing the captain and his team to pinpoint and eliminate the enemy. While leading an attack on the last remaining pillbox in the grove, however, Wai’s luck ran out, its defenders killing him before they themselves were overrun. According to a subsequent posthumous citation, “Capt. Wai’s courageous, aggressive leadership inspired the men, even after his death, to advance and destroy the enemy.” By late afternoon Red Beach was securely in American hands.

At 6 p.m. that day a burial detail interred Wai in a makeshift American military cemetery in Palo. Repatriated in 1949, his remains were reinterred with full military honors that September 8 at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (aka the “Punchbowl”) in Honolulu. Wai’s parents and 100 relatives and friends were in attendance.

In the wake of Wai’s actions on Red Beach his regimental commander, Col. Aubrey Newman, had recommended the hard-charging captain for a posthumous Medal of Honor, but the Army instead had awarded Wai the Distinguished Service Cross. In 1996, however, allegations of past prejudicial treatment of Asian American service members led Congress to direct the Army to review the records. As a result the branch upgraded 22 DSCs granted to Asian Americans to Medals of Honor. All but two were granted to Japanese Americans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and 100th Infantry Battalion. One of the two went to Rudolph D. Davila, a Texan of Spanish-Filipino descent, for his heroism at Anzio, Italy, in May 1944. The other went to Wai.

On June 21, 2000, President Bill Clinton presented Robert Wai the Medal of Honor on behalf of his late brother Francis—the only American of Chinese ancestry yet to have received the United States’ highest medal for valor. MH