Colonel William Irwin’s 6th Corps brigade of Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith’s 2nd Division was an experienced unit, whose regiments were mustered into service between May 9, 1861, and November 23, 1861. They participated to varying degrees in all combat during the Peninsula Campaign and Seven Days Battles.

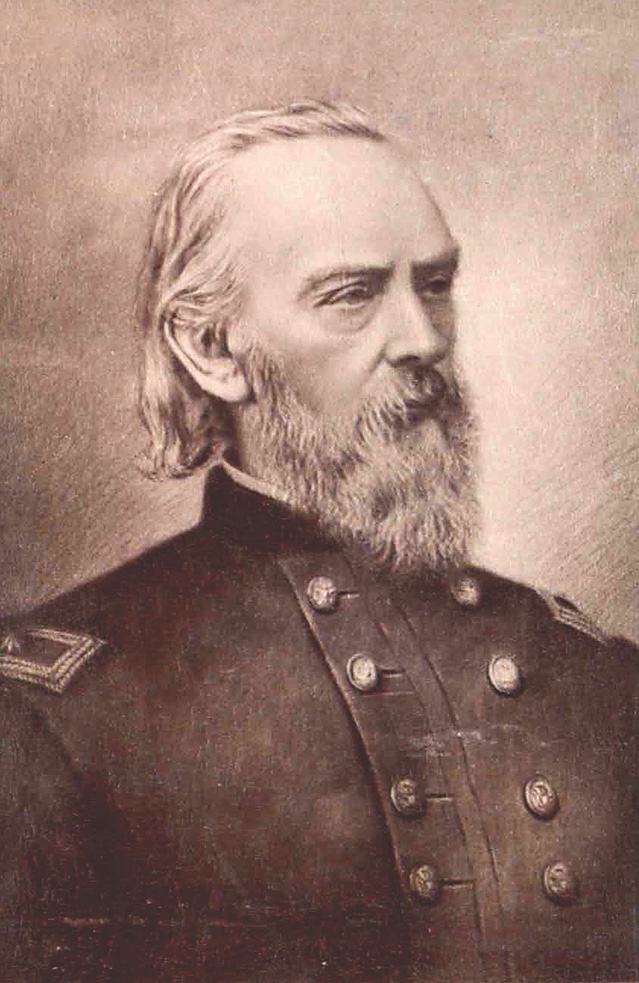

Pennsylvanian William Howard Irwin was born in 1818 and attended Dickinson College for two years before returning home to study for the bar. He entered the Army in February 1847 and received a commission in the 11th U.S. Infantry. Irwin was seriously wounded at the Battle of El Molino del Rey on September 8, 1847, during the war with Mexico, while leading his company. He received a brevet to major for his bravery and returned to Pennsylvania to practice law until the outbreak of the Civil War when he again donned a uniform. He enlisted as a private after the fall of Fort Sumter but quickly rose to the rank of colonel of the 7th Pennsylvania Volunteers, a 90-day unit that participated in the early advance on the Shenandoah Valley in June–July 1861.

After the regiment mustered out, Irwin assisted in raising and organizing several Pennsylvania units. He was appointed colonel of the 49th Pennsylvania in late 1861. Several of his subordinates brought charges against him for drunkenness and “conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline.” He was acquitted on the first charge but convicted on the second, drawing an inconsequential suspended punishment. He went on to lead the 49th with distinction during the Peninsula Campaign. He was given a brigade in the 2nd Division in the 6th Corps prior to the advance into Maryland.

Irwin’s brigade left Camp California, near Alexandria, Va., and eventually crossed the Potomac River at Long Bridge, camping near Georgetown on September 7. The column subsequently marched through the Maryland towns of Rockville, Barnesville, Darnestown, and Jefferson, toward Catoctin Mountain. On September 14, the brigade trudged through Burkittsville to support William T.H. Brooks’ brigade (also of Smith’s division) at Crampton’s Gap. The brigade was subjected to enemy artillery fire as it hurried through the town but sustained no casualties. The men spent the afternoon and evening supporting Captain Romeyn Ayres’ divisional artillery and camped at the gap until Wednesday, September 17, when they began their march toward Antietam Creek. Irwin’s brigade reached its destination at 10 a.m. and crossed Antietam Creek at Pry’s Ford, where it was called into action by Smith to relieve troops from Maj. Gen. George S. Greene’s division of the 12th Corps.

Brigadier General William French’s division (2nd Corps) launched charge after charge against the Sunken Road during this time. To relieve pressure on D.H. Hill’s two brigades defending the road, wing commander James Longstreet directed a counterattack meant to land on French’s vulnerable right flank. John Cooke of the 27th North Carolina led his regiment and the 3rd Arkansas (Colonel Van Manning’s Brigade in Brig. Gen. John Walker’s Division) out of the West Woods and against French’s flank. The ambitious band assisted in routing the left of Greene’s division holding the Dunker Church and then crossed Hagerstown Pike, setting their sights on the Union soldiers clearing out the Sunken Road.

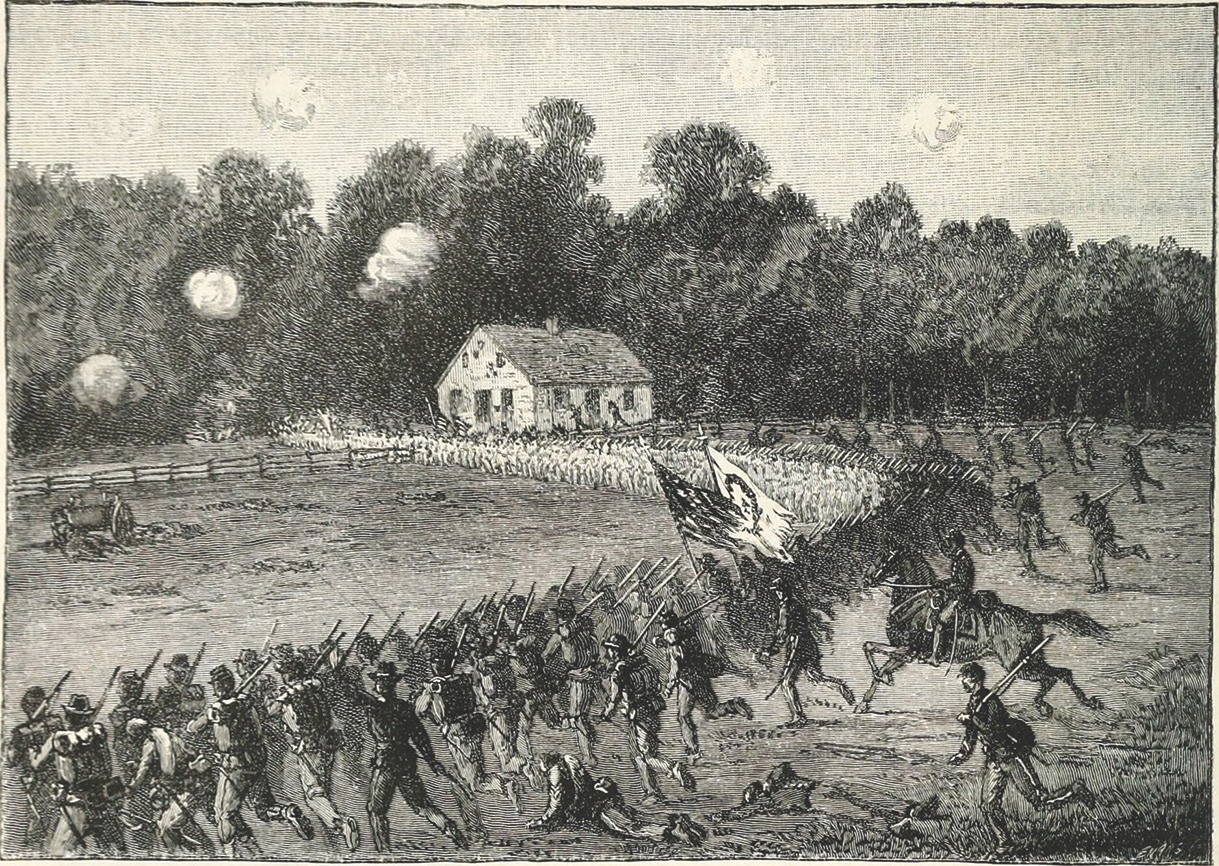

Irwin threw the 33rd and 77th New York out as skirmishers on the right of the brigade along Smoketown Road. The rest of the brigade was oriented south-southwest with its right on the road. The large 20th New York led the advance, the 49th New York followed on its right, and the 7th Maine advanced on its left en echelon. The 20th New York cleared the East Woods with Smith riding behind the regiment. As the three regiments dashed past the southern edge of the East Woods, they encountered retreating elements of Greene’s division. They then moved through Lieutenant Evan Thomas’ 4th U. S. Artillery, Battery A, firing at the enemy in the West Woods.

Farther south, Cooke’s Confederate assault force climbed over the fences lining Mumma Lane and entered a cornfield. Before Cooke’s men could attack French, they were hit by John Brooke’s brigade (Israel Richardson’s 1st Division, 2nd Corps) that was rushed toward the Roulette Farm buildings from the east to halt the two enemy regiments. The 7th Maine also rushed forward to add its support from the north. While Brooke’s men fired into the enemy’s front, the 7th Maine fired into the left flank of the 27th North Carolina. The intense fire in their front and flank was more than Cooke’s men could handle and they broke in confusion, followed closely by Irwin’s men.

While the 7th Maine was engaged with Cooke, the 20th New York came to a rise in the ground just to the east of the Hagerstown Pike that had sheltered Greene’s men earlier in the day. It was ordered to halt there, but the New Yorkers kept going until they were driven back by small arms fire from Manning’s Brigade and an enemy battery stationed near the West Woods. The New Yorkers quickly retraced their steps to the high ground and lay down behind the hill. They were soon joined by the 49th New York who also took cover. After repulsing Cooke and clearing the Mumma Farm buildings, the 7th Maine also returned to the brigade, lying down behind the hill on the left of the 20th New York.

The 33rd and 77th New York, on the skirmish line to the right of the rest of the brigade, had their own share of excitement. As they headed toward the West Woods, with the 33rd New York on the right of the Smoketown Road and the 77th New York on its left, they were closely watched by the 49th and 35th North Carolina (Robert Ransom’s Brigade in John Walker’s Division). The Tar Heels hopped behind a rail barricade they had previously built just north of the Dunker Church. Irwin explained what happened next: “A severe and unexpected volley from the woods on our right struck full on the Seventy-seventh and Thirty-third New York, which staggered them for a moment, but they closed up and faced by the rear rank, and poured in a close and scorching fire.”

Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Corning of the 33rd New York reported his regiment was “in columns at the time, marching by the right flank. This sudden and unexpected attack caused a momentary unsteadiness in the ranks, which was quickly rectified. The battalion faced by the rear rank and returned the fire.” Captain Nathan Babcock of the 77th New York claimed the two lines were so close that “you could see the white of their eyes.” The historian of the 49th New York claimed its two fellow New York regiments were “losing frightfully, and would doubtless have been annihilated had not General Smith seen their predicament and sent an aide to their rescue, who faced them by the rear rank and placed them behind the ridge, at right angles with the other regiments of the brigade.” The brigade re-formed in the safety of the Mumma swale.

The swale sheltered Irwin’s men from the enemy’s small arms fire but not from their artillery and sharpshooters. The brigade also found itself in the uncomfortable position between dueling Union and Confederate artillery, causing considerable uneasiness among the men in the ranks.

A Confederate battery fired along the flank and through the line of the 20th New York, which, from the nature of the ground, was compelled to refuse its left, and thus received the fire along its entire front. Sharpshooters from the woods to the right and to the extreme left also opened upon the brigade. Shell, grape, and canister swept from left to right. The enemy fired quickly and accurately, causing Irwin’s losses to accelerate. The historian of the 49th New York recalled, “the whirring shells and screaming shrapnel going both ways over their prostrate forms, reduced the most corpulent of the men to very thin proportions.”

Major Thomas Hyde and his 7th Maine found themselves better protected by large boulders along their line and were able to see the Irish Brigade’s (Richardson’s Division, 2nd Corps) notable colors and the Union line finally breaching the Sunken Road, as well as artillery playing along the right of the line from Confederate batteries near the Dunker Church. The Germans of the 20th New York on the right, having only flat ground to lie on for protection, suffered mightily, and a stream of wounded headed for the rear. The regiments occupying protected terrain, such as the 7th Maine, lost but few men. At one point, Hyde suggested to Colonel Ernst von Vegesack of the 20th New York that the Confederates could possibly be sighting in on the 20th’s regimental colors being held high.

Most of the brigade remained in this position, subjected to heavy artillery and sharpshooter fire for 24 hours, until relieved by a brigade from Maj. Gen. Darius Couch’s 4th Corps division (attached to the 6th Corps) on September 18. The 7th Maine did not stay inactive, however. The rugged men were dead shots and were deployed as sharpshooters against the Confederate artillery positions. One Maine sharpshooter known by the name of “Knox” drove every man from the guns of one section and knocked an unknown general officer from his horse in the distance.

At about 4:30 p.m., Colonel Irwin became concerned about Confederate troops he could see moving across Reel Ridge to the west, on the other side of the Hagerstown Pike, who appeared to threaten the division’s left flank. Heavy fighting could be heard in the direction of Sharpsburg. The hills blocked most views of troop movements to the left, where the 5th and 9th Corps were in action. Irwin watched the Confederate columns and worried they could be supporting Lee’s right flank, now under attack. Irwin sent word to Smith requesting artillery support, and the division’s chief of artillery, Captain Emery Upton, complied. Captain John Wolcott’s Maryland Light Battery arrived as ordered and dropped trail with its three rifled guns. These guns threw a destructive cannonade against the enemy positions for half an hour before being replaced by Lieutenant Edward Williston’s 2nd U.S. Artillery’s six Napoleons. Enemy sharpshooters from D.H. Hill’s Confederate division began firing at the cannoneers from the Piper Orchard, causing Irwin to look to his best unit available to put an end to the sniping. He again turned to the 7th Maine.

Hyde led his men toward the new target, the Piper Farm building complex, about half a mile away, firing while crossing the Sunken Road filled with enemy dead and dying.

The beginning of the 7th Maine’s memorable charge began as badly as it ended, with supporting Union guns accidentally firing into Hyde’s men, dropping four. Enemy soldiers in front of, and to the left of, Hyde’s men realized they were in danger of being cut off and ran for safety, clearing out the orchard. Hyde quickly obliqued his men to the left to take cover behind a ridge, on the south rim of the cup, running from behind the Piper barn to Hagerstown Pike. As Hyde rode up the high ground, he quickly took in the danger around him. Lying down in front of his men was a line of enemy troops from George T. Anderson’s Brigade and another body led by D.H. Hill himself, rushing along Piper Lane to his left in an effort to cut off his retreat.

With the enemy in front, and closing on his right, Hyde quickly realized it was time to retreat. He ordered the regiment to move by the left flank before Hill’s men saw them, and double-quickened his men past the Piper barn, through a forced opening in the picket fence, and into the orchard. Additional troops, remnants of Cadmus Wilcox’s and Ambrose Wright’s brigades (both of Richard Anderson’s Division), still full of fight, headed for Piper Lane and opened fire just as Hyde’s men passed through the fence. Hyde’s men returned the fire and then Hyde instantly sent his men up the hill in the middle of the orchard, where they again halted to fire into G.T. Anderson’s men and others who were hurrying toward them.

Hyde and the remnants of his regiment quickly retraced their steps back across the Sunken Road to the safety of the rest of the brigade hunkered down in the Mumma Farm swale. The 7th Maine won accolades for its actions at the Piper Farm and Hyde received the Medal of Honor, albeit at great cost.

Irwin’s brigade occupied the battlefield for 26 hours until relieved at noon on September 18. Irwin summed up his brigade’s actions during the battle: “It was under fire constantly during this time in a most exposed position, lost 311 in killed and wounded, yet neither officers nor men fell back or gave the slightest evidence of any desire to do so. My line was immovable, only anxious to be launched against the enemy. I forbear comment on such conduct. It will commend itself to the heart and mind of every true soldier.”

This article is excerpted from: Brigades of Antietam edited by Bradley M. Gottfried. Copyright © 2021 by The Antietam Institute. Published by The Antietam Institute, antietaminstitute.org