The great quest to pilot an aircraft has been accomplished, proclaimed the New York World newspaper on August 4, 1895. “A World reporter has succeeded in flying for hours here and there, backward and forward, up and down in the air,” wrote the unnamed reporter who had just flown Carl Myers’ airship in the skies over New York and lived to tell about his thrilling adventure.

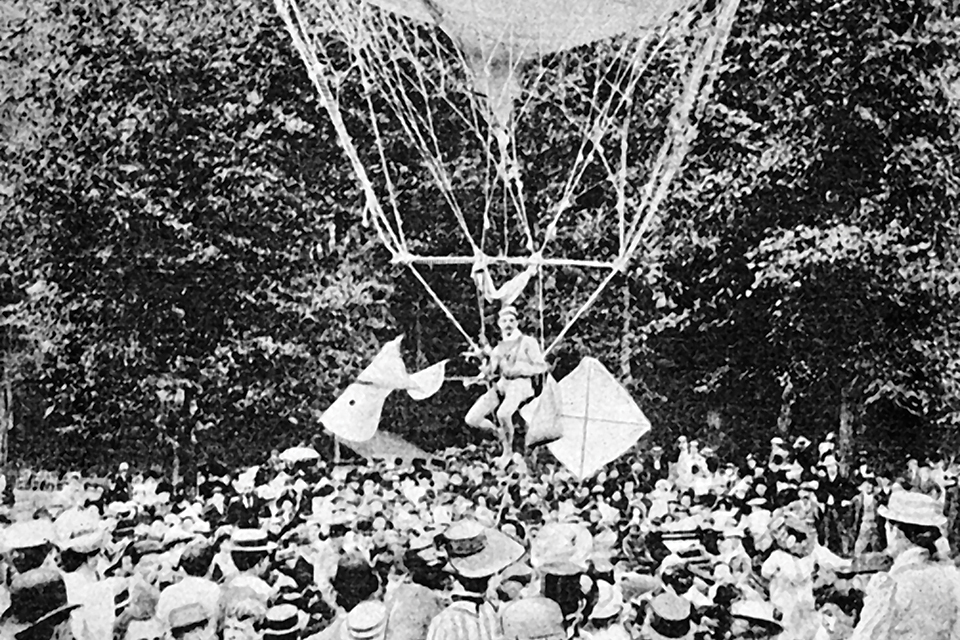

Years before the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, “Professor” Myers was piloting his pedal-powered balloon, amazing the crowds below at county fairs and amusement parks in airships variously dubbed the Sky-Cycle, Aerial Bicycle and Air Velocipede. “With the aid of a bicycle attachment and a pair of wings, the problem has been solved,” wrote the World.

The first successful tests in 1783 by the Montgolfier brothers of their hot-air balloon stirred the world’s imagination, and the race to create a maneuverable powered aircraft was on. But what would provide the power?

In the late 1880s the invention and widespread adoption of the safety bicycle sparked a bicycling craze. It wasn’t long before someone had the idea of placing a bicycle-like device underneath a balloon. The pilot worked the pedals, which turned the propellor or propellers, and the craft moved forward or to the right or left. Or in a circle. The balloon provided the lift; the pedals and propellers added thrust. It was simple physics.

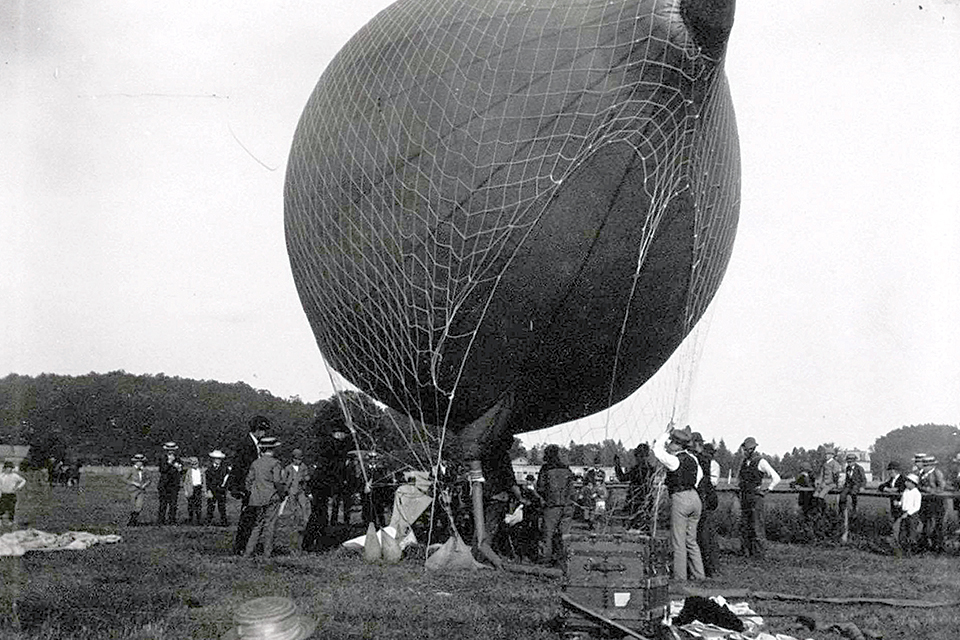

Born in upstate New York in 1842, Carl Edgar Myers began constructing and flying hydrogen-filled balloons in the late 1870s. His wife, Mary, helped with the manufacture on their “Balloon Farm” in Frankfort, N.Y. She eventually joined Myers as he toured the country. Billed as Carlotta, the Lady Aeronaut, she jumped from balloons with a parachute.

The Myers were issued a patent on May 26, 1885, for a “Guiding Apparatus For Balloons.” There was no bicycle underneath—not yet—just a rudder on one side of the basket and a helical “screw-sail” on the other that the pilot turned by hand to steer the airship. It took another couple of years for Myers to add pedals and a propeller to his maneuverable balloon.

“Prof. Carl Myers has made several satisfactory tests with his new invention, the air velocipede, which will soon be in shape to give public exhibitions of its workings,” reported Pennsylvania’s Altoona Times on April 17, 1889. Myers tinkered with and improved his aircraft, and soon began touring the country, demonstrating it to crowds of amazed onlookers.

“This is no hot air hocus-pocus where the so-called ‘aeronaut’ goes up about as high as a church steeple and then comes down, but an actual flying machine, that speeds and spins in the air like a bird,” wrote Ohio’s Hamilton Evening Journal on August 31, 1892. “It is worked by foot pedals like an ordinary bicycle, but goes through the air instead of on the ground….It has made numerous outdoor exhibitions before thousands of people, and has never failed to rise and move away at the will of the rider.”

By mid-1895, Myers had further improved his airship, adding wings for greater stability and ease of turning. To drum up even more publicity, and to prove that he was the world’s greatest aeronaut, Myers made his machine available to the World, one of New York’s largest newspapers. The reporter who took it up wrote breathlessly that “No living human being on any other contrivance has ever done these extraordinary things in the air. No one else has succeeded in going against the wind. No other machine was ever able to stand still in the air….And no machine ever constructed could turn around in the air and travel backward. The wonderful flying machine does all these things.”

According to the reporter, he was able to make his way “though a forty mile breeze [that] was blowing from the South.” Several times he returned to the spot in Brooklyn where he had lifted off so that he might acknowledge, with a tip of his cap, “the mighty cheering of thousands of unfortunate mortals who were tacked to the earth.”

The reporter/pilot then waved farewell and headed north, at an altitude of about 1,000 feet. Later, after releasing ballast, he rose to about 2,000 feet. “After some maneuvering, however, a safe landing was made on an open field, about one mile east of Yonkers,” he wrote.

Myers received a patent for his “Sky-Cycle” on April 20, 1897.

Despite the story in the World, which ran in newspapers around the country, Arthur W. Barnard claimed he had invented the flying bicycle balloon. “Professor” Barnard gave a demonstration in Nashville in early May 1897. According to a newspaper report, “Rising as gracefully as a bird, he soared to a height of fifty feet, sailing against a somewhat stiff breeze….” After 12 miles, a propeller mishap forced him to land.

Myers was understandably miffed when he learned of Barnard’s claim. He shot off a telegram to the World, which ran it along with a detailed description and drawing of the 1895 flight. In the telegram, Myers wrote that Barnard’s airship was “built wholly by me here under my patent of this year, different only from World airship in elongated spindle….The operator had no part in designating this skycycle airship, but paid for and received my best work.”

Myers continued to harvest his crops on the Balloon Farm into the early years of the next century and made some demonstration flights at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where he also served as superintendent of the Aeronautics Concourse. And then along came the Wright brothers. Myers, his balloons and the Sky-Cycle were yesterday’s news. Myers and Mary/Carlotta retired from “farming” and flying in 1909, and moved to Atlanta to live with their daughter.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe!