For World War II Iwo Jima Marine and Silver Star recipient Thiele Fred Harvey, 97, crossing the finish line during the Marine Corps Marathon in October brought him full circle in a long list of accomplishments that began with his enlistment in the Marine Corps some 78 years ago.

Being pushed in a custom-made “racing chariot,” as he called it, during the virtual race in Fredericksburg, Texas, on Oct. 25, Harvey got up and took to his walker for the last few steps of the 26 miles.

“They rolled me around all over this part of the country and I got to meet a lot of people along the way that wanted pictures, of course,” Harvey said. “We obliged them.”

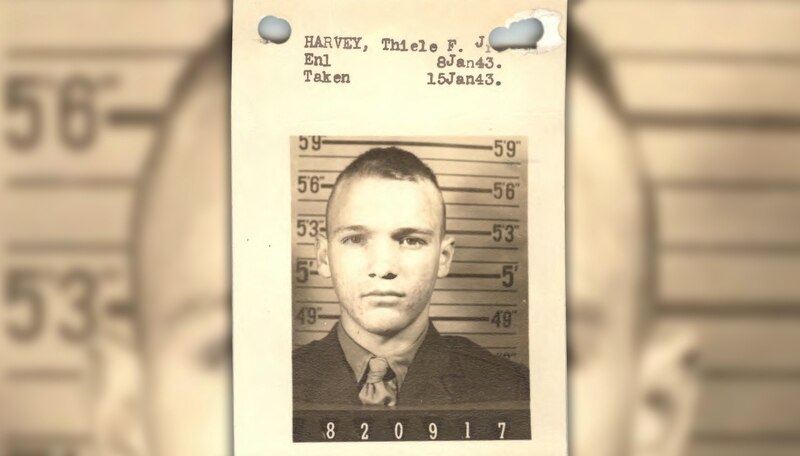

Before joining the service at 19 years old in January 1943, Harvey worked part time as a roughneck on the oilfields of Texas, contending with unwieldy oil pipes that sputtered the crude all over to earn money to support his mother and sisters.

Harvey served with grit and pride, surviving three beach invasions of America’s island-hopping campaign during the Pacific War, when he saved a fellow Marine from deadly Japanese machine-gun fire ― for which he earned the Silver Star ― and was later seriously injured by two grenades in a three-grenade sneak attack on Iwo Jima before leaving the Marine Corps in November 1945 as a private first class.

Harvey’s and his other Marines comrades, assault troops of the 5th Amphibious Corps, earned a Presidential Unit Citation for the seizure of the Japanese-controlled stronghold of Iwo Jima.

According to Harvey’s service record, acquired by Marine Corps Times from the National Archives, he received parachute and swim qualifications in preparation for attacks by air and amphibious assaults. He was primarily a demolition specialist with secondary qualifications as a rocketeer.

After his service, Harvey decided to get more education. He earned a higher degree and taught high school history and sports, leaving his impression on several generations of Texas youth.

Three-man patrol

“Click.”

The distinctive sound of a Nambu Type 99 light machine gun made Harvey’s ears perk up. He knew the Japanese soldier was reloading and it was only a matter of time before a barrage of bullets was unleashed.

Harvey yelled for his squad mate to hit the deck. The soft, dark volcanic sand yielded a little to the impact of his body.

“Well, the guy next to me, his name was Dempsey, and he didn’t hit the deck fast enough, and the bullet got him in the back,” Harvey told Marine Corps Times.

The Marines had taken refuge in a shallow hole blasted into the sand of a pockmarked Iwo Jima. The Japanese island had been hit hard by American bombardment, meant to “soften” the battleground for the Feb. 19, 1945 invasion. Harvey was part of the 26th Marines and one of 70,000 Marines who took part in the 36 days of fighting.

The two of them had been left behind by their squad leader, “Irvin,” who ran from the machine-gun fire, Harvey said.

The three Marines volunteered to go out on patrol the night after the invasion to search for another company of Marines who went missing.

Irvin eventually found his way back to Company C’s position and alerted his command of the situation and a rescue team was deployed to search for Harvey and Dempsey.

But for the time being, the two Marines were alone to contend with the Japanese soldier, hunkered down in a nearby crater. With Dempsey injured, Harvey knew they had to escape. He also knew that if they stayed low, they’d be safe. The Nambu LMG boasted a deadly rate of fire of 800 rounds per minute that could mow down its targets with ease ― that is, as long as those targets were relatively perpendicular to the ground.

Because the Japanese soldier was in a hole, he had a hard time getting the back of the gun high enough to compensate for the Type 99′s already high angle of fire. Without potentially exposing himself to bullets Harvey returned from the .45 pistol his mother had bought him back in Odessa, Texas.

“Every once in a while, I’d give him a few shots over there into his hole, let him know that I was still in business, and he left us alone,” Harvey said.

When the rescue squad arrived and got within earshot, Harvey relayed the situation.

“And I said, ‘I’ll just throw that thermite grenade out and it’ll tell you just about where we are, and then you can work on it,’” Harvey said.

Harvey had to quickly execute his rescue and escape. To complicate matters, he noticed the thermite grenade strapped to Dempsey’s hip was ruptured, no doubt by one of the first Japanese bullets, and was likely to explode any minute.

“It was just ready to break loose and set us on fire right fast,” Harvey said.

Thermite was used during World War II to melt the barrels and works of heavy enemy guns and equipment. When ignited, the incendiary grenades burn at several thousand degrees and fuse to the metal of the weaponry, rendering it inoperable.

Harvey, originally a Marine paratrooper, was a demolitions man during the Battle of Iwo Jima in Japan. He knew he had little time to dispose of the incendiary grenade.

“I took my Ka-Bar knife and cut that part out of the belt and got that thermite grenade out of there,” Harvey said. “And sure enough, when I threw it out it began to burn. And we was just lucky it didn’t do it while I was in the hole with it.”

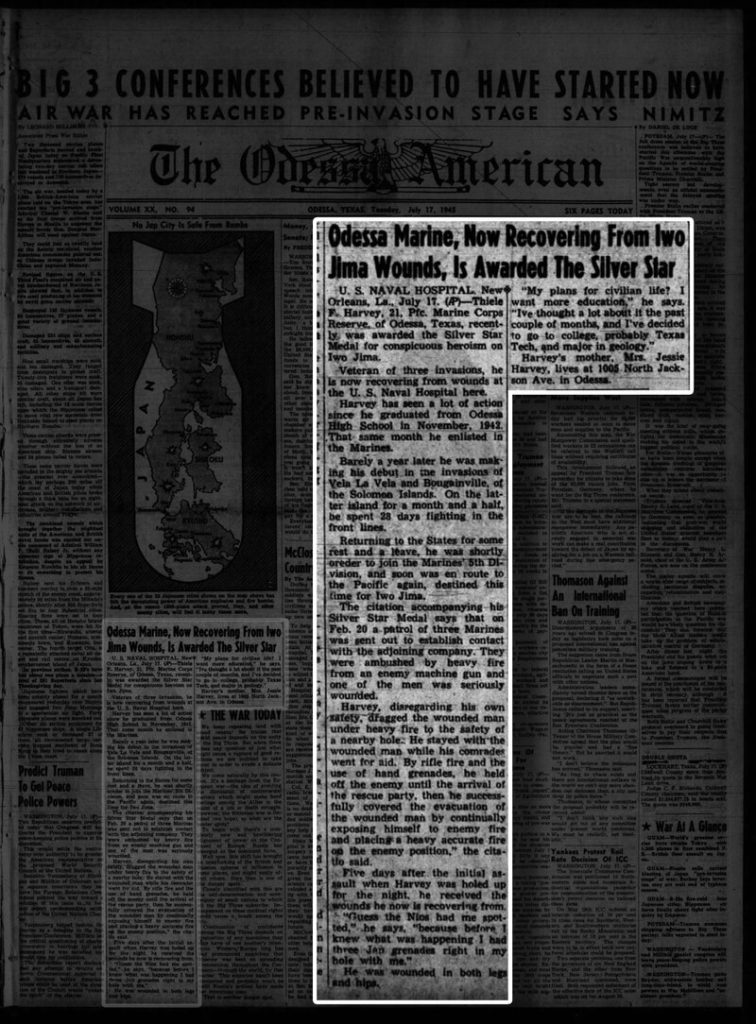

With covering fire from the rescue squad, Harvey dragged Dempsey out of the small crater and away to safety. For his heroism, Harvey was soon after awarded the Silver Star and was recognized in his hometown paper, the Odessa American.

Three grenades and a Purple Heart

A little less than a week later, Harvey’s resolve was once again tested.

It was 9 p.m. and Harvey was laying down in a hole in the ground he had claimed, trying to wind down and get his allotted three hours of sleep. The Marines slept in shifts and were under orders to remain in their holes or risk taking friendly fire. Japanese soldiers had been sneaking into the Marine camps and tossing grenades into sleeping holes, so the Marines pulling watch were told to immediately shoot anyone they saw walking around in the area at night.

A sergeant asked Harvey if he could borrow his pistol while on watch. Harvey obliged.

It was about midnight when Harvey was startled out of his deep sleep by two pistol shots.

Then the first grenade landed near him.

“So, I jumped up,” Harvey said. “I was scared. This is where fear really paid off for me. … I was pretty close to it, and I was able to catch it and toss it out of the hole.”

The grenade exploded at a safe distance from him.

The fear caused Harvey’s brain to flood his body with adrenaline. Though he was fast asleep only seconds before, the rush made him alert and his reflexes quick.

Harvey heard another thump and he knew the Japanese soldier was going to throw a second grenade.

“And he was going to hold it for two or three seconds before he threw it,” Harvey said. “He didn’t want me to throw it back out at him.”

The second grenade came in and Harvey tried catching it, but fumbled it in his hands a few times before dropping it. The grenade now on the ground, Harvey tried to kick it away with his left foot. He missed and the grenade exploded, badly damaging his left leg. Harvey fell to his back and quickly shifted in the volcanic sand to get to his side, expecting to receive another grenade.

Harvey heard another thump. A third grenade, this one likely “cooked” for longer so he would have less time to return it.

“They had a six second fuse on it, and six seconds passes pretty fast when you’re working with something like that,” Harvey said.

The grenade landed next to him, but Harvey lacked the mobility or the strength to throw it back. He quickly shuffled his hip onto the grenade and it sunk into the loose soil before exploding.

“That thing went off then it threw me about halfway out of the hole,” Harvey said.

Harvey was awarded a Purple Heart for injuries sustained during the encounter.

Iwo Jima was Harvey’s third and final invasion. During the Pacific War, he participated in the American invasions of the Vella Lavella and Bougainville Islands in the Solomons.

[hr]

Originally published on Military Times, our sister publication.