World War II ended in Europe on May 8, 1945. But for most of the continent, including its millions of displaced persons and those trying to rebuild their lives in ruined cities, it would be years before peace returned. Released in 1949, The Third Man takes place in a postwar Vienna ravaged by Allied bombing raids that destroyed 20 percent of the city and left 270,000 residents homeless. (Director Carol Reed insisted that the film be shot on location, and viewers can see for themselves the hills of rubble.) Like Berlin, the city is occupied by four Allied powers: the Americans, British, Soviets, and French. And with chronic shortages of everything from food to medicine, it’s the heyday of the black market, in which everyone seems to participate a little—and some a lot.

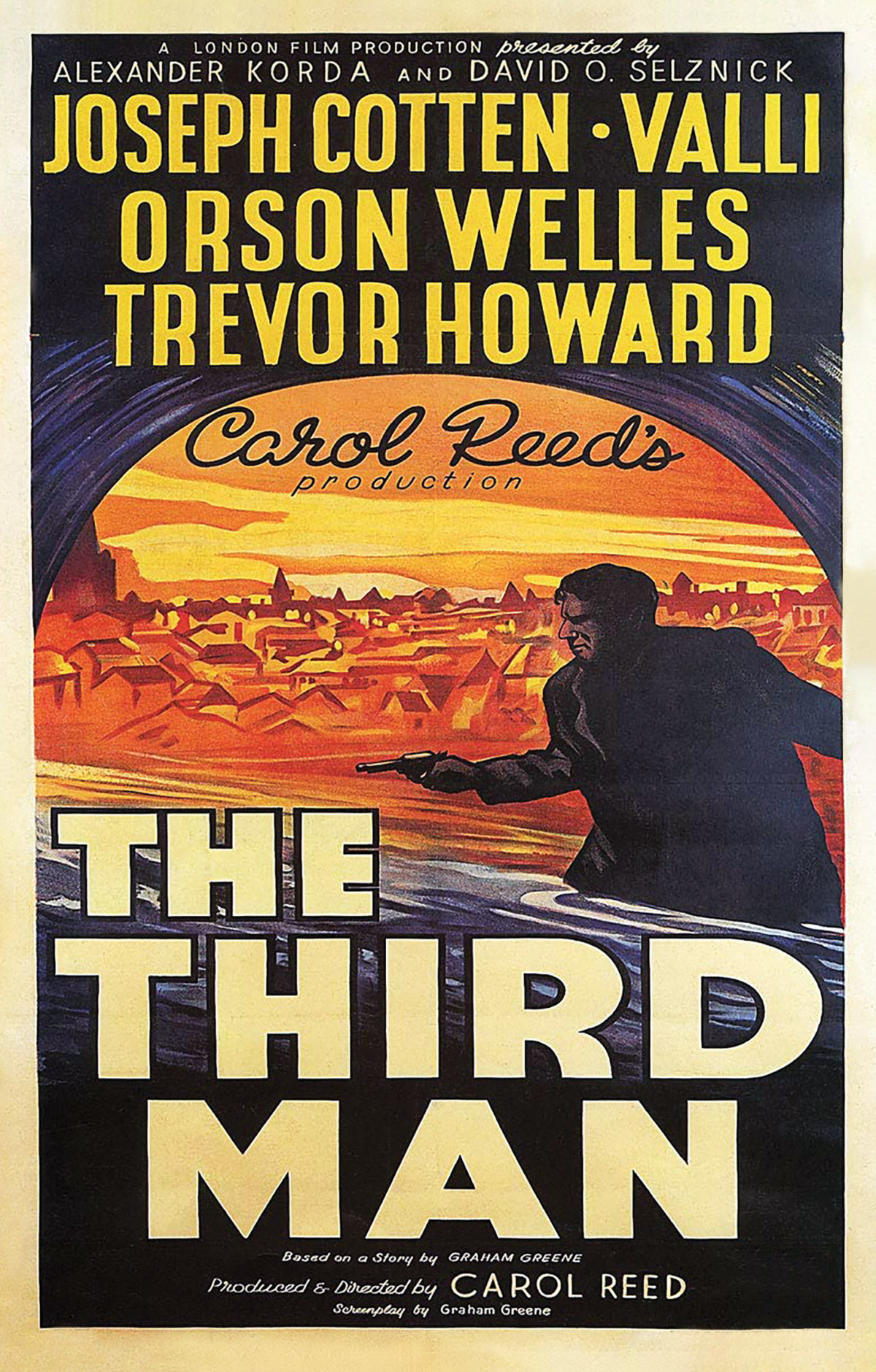

Into the city arrives Holly Martins (actor Joseph Cotten), a hack American novelist who has received an invitation from an old college chum, Harry Lime (Orson Welles), to come work with him in Vienna. (The nature of the work is never made clear.) Complications arise when Holly learns that his friend Harry is dead, killed in a recent traffic accident. Adding to his troubles is British military policeman Major Calloway (Trevor Howard), who curtly informs Holly that death was “the best thing that ever happened” to Harry, and that it was a fate befitting a black marketeer who was also a murderer. Outraged, Holly decides to clear Harry’s name and destroy Calloway’s reputation.

Everyone discourages Holly’s efforts to learn more about Harry’s death—especially Harry’s friends in Vienna, who provide accounts that don’t quite jibe and also omit a key detail that Holly soon learns from Harry’s onetime porter: that in addition to the two men these friends say carried off Harry’s body, there was also “a third man” involved. The porter is mysteriously murdered after this reveal.

The film is nearly complete before we learn the identity of the third man (and consider reading no further until you’ve seen the film yourself, which among many critics is considered to be one of the best ever made). After Calloway decides to exhume Harry’s coffin to verify his “traffic accident” death, the body turns out to be that of a missing medical orderly, not Harry Lime. In fact, Harry himself killed the man lying in the coffin and is alive and well, evading authorities in the city’s Soviet sector.

By this time Holly knows why Major Calloway considers death the best thing that ever “happened” to Harry. Harry has made a fortune selling penicillin on the black market, diluting it so that it is worse than useless, and is thereby responsible for the demise of countless hospital patients. “Men with gangrened legs, women in childbirth,” Major Calloway informs Holly right before the film’s big twist. “And there were children, too. They used some of this diluted penicillin against meningitis. The lucky children died. The unlucky ones went off their heads…. That was the racket Harry Lime organized.”

In one of the movie’s best-known scenes, Holly and Harry meet in a gondola of the Riesenrad, the famous Ferris wheel at the entrance to Vienna’s Prater amusement park. Harry is self-assured, silky, and unrepentant. Gesturing toward the pedestrians far below, he asks Holly, “Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you 20,000 pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money, or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?”

Given that the movie’s audience has already viewed laborers hard at work atop the city’s ubiquitous mounds of rubble, it is not hard to recognize that not long before, those same “dots” were the targets of Allied bombers. “Nobody thinks in terms of human beings,” Harry continues, making substantially the same point. “Governments don’t. Why should we? They talk about the people and the proletariat; I talk about the suckers and the mugs. It’s the same thing.”

But is it? We the audience don’t want to think so. We don’t want to share Harry’s chilling cynicism. Holly doesn’t share it, and Calloway decidedly does not as well. The Third Man’s genius, however, is that it does not entirely let us off the hook. It doesn’t ask us to sympathize with Harry, though Holly cannot escape a sense of sorrow once his wayward friend receives his just deserts at the film’s end. But it conveys a sense that Harry isn’t entirely wrong about the world we inhabit. The wickedness of war may be the essence of humanity.