It’s commonly known that the Purple Heart is the oldest American military decoration, proposed by Gen. George Washington as the Badge of Military Merit in 1782 to honor soldiers who performed gallantly during the Revolutionary War. But many people may be surprised to learn that the award went away soon after the fight for independence ended—and did not re-emerge until 1932.

That year, 137 World War I veterans received Purple Hearts by order of the Army’s chief of staff, Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Those medals, which honored “every species” of meritorious military service, went only to Army troops. In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the Purple Heart for members of the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and designated the award specifically for troops wounded or killed in action.

“If you shoot yourself in the foot, you don’t get a Purple Heart. If the enemy shoots you in the foot you get a Purple Heart,” said Doug Greenlaw, National Commander of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, or MOPH, a 46,000-member veterans services organization founded in 1932. “It has to come from the enemy. There’s usually blood involved. If you get wounded by the enemy, you get a Purple Heart.”

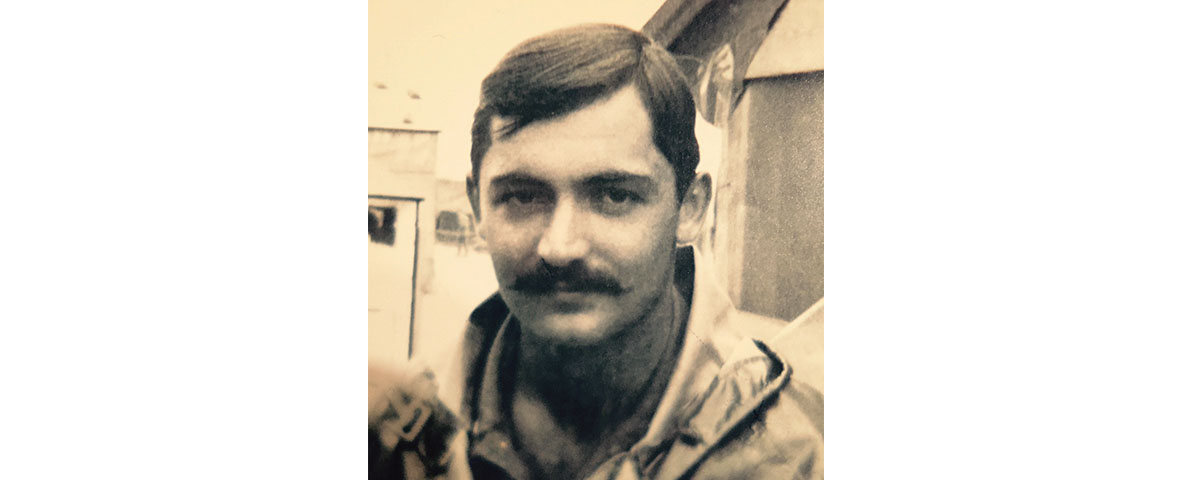

Some 1.7 million Purple Hearts have been awarded to service members since the United States entered World War II, including about 350,000 to troops who served in the Vietnam War. Greenlaw was wounded twice in an action-filled tour as a first lieutenant in Company D, 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 196th Light Infantry Brigade. The Michigan City, Indiana, native joined the Army in 1965 after two years of college. He completed Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Jungle Expert School in Panama, then was shipped to Vietnam, arriving in August 1967.

That fall, platoon leader Greenlaw was wounded during a big firefight on Hill 63 just west of Da Nang. As his unit was being overrun by the North Vietnamese, Greenlaw called in airstrikes on his own position. His soldiers, as well as the enemy’s troops, suffered heavy casualties. The wounded Greenlaw stayed with his platoon until all of the men were accounted for and evacuated. In November, he was awarded the Silver Star.

“I had a light wound in my right leg, which took about three or four weeks to heal in-country,” Greenlaw said. “And then in December I went back out.”

In April 1968, Greenlaw, who had been promoted to Delta Company commander, was severely wounded when his point man tripped a booby trap while the company was on patrol. Greenlaw was medevaced to a MASH unit, a mobile army surgical hospital, where “they gave me the last rites,” he said. “I was wounded really seriously in the face and neck—mainly the neck—and had a compound fracture in my right leg. And I lost my left kneecap. A piece of bamboo nailed my left arm to my chest. I was a mess.”

Greenlaw indeed was a mess, but he survived.

“I was 23 and in really good shape,” he said. “They stopped the bleeding. Then they sent me in a helicopter to the [95th Evacuation] Hospital in Da Nang and put me back together. Then they put me in a body cast and sent me to Yokohama, Japan, for plastic surgery and repairs. They put my leg back together and did some experimental surgery, from what I understand, on my face and nose and the left side of my jaw.”

Greenlaw was sent back to the States for more rehab and recovered from most of his wounds at Fort Sheridan near Chicago. He was honorably discharged with a medal collection that included two Bronze Stars in addition to the Silver Star and two Purple Hearts.

The Army veteran returned to college and earned a bachelor’s degree in communications from Indiana University. Greenlaw embarked on what became a successful career as a media executive, including president of sales and promotional marketing for Viacom’s MTV Networks, which encompass MTV, VH1, Nickelodeon, Nick at Night and TV Land, and CEO of Multimedia Inc., whose holdings included print, radio, TV and cable properties. Today, he lives in Greenville, South Carolina, where he is chairman of Community Journals, a publishing company he founded.

In 2008, Greenlaw co-founded and led the Greenville chapter of MOPH, which has its national offices Springfield, Virginia, a Washington suburb. He was the 2015-16 South Carolina state commander and was elected 2018-19 national commander at MOPH’s convention in August 2018.

Full membership in the MOPH, which receives most of its funding from grants, is open to active duty and discharged individuals who have received the Purple Heart for wounds suffered while serving in the military of the U.S. or any foreign country during combat against “an armed enemy of the United States.” Like other congressionally chartered veterans services organizations—such as the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Disabled American Veterans and Vietnam Veterans of America—the MOPH operates a nationwide service officers program that helps veterans obtain their earned federal benefits and a Veterans Affairs Voluntary Services program that coordinates the activities of member volunteers in more than 100 VA medical centers across the nation. MOPH also has an active lobbying presence on Capitol Hill.

A good deal of MOPH’s work is done by its 478 local chapters. “It all boils down to our chapters, where the rubber meets the road, and our service officers,” Greenlaw said. “We have 70 service officers across the country who are very busy consulting and working with vets to work through the bureaucracy of the VA and whatever problems they might have.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder, he said, “is a major issue” among Purple Heart recipients. “I believe that every combat-wounded vet, 100 percent, has PTSD to one degree or another,” Greenlaw said. “I have just a little bit. It doesn’t really bother me. But if I have 2 percent, some have a hundred percent. They need service dogs. They really struggle through life. PTSD is real.”

Wounded Vietnam War veterans make up about two-thirds of the nation’s 500,000 living Purple Heart recipients (and about the same percentage of MOPH members), and many are helping their fellow wounded veterans. “About 80 percent of Vietnam vets are retirement age,” Greenlaw said. “The good news is that about half of them are healthy. Since they’re retirement age, they’re empty nesters, or whatever else it might be, they have time to work with the MOPH. That’s a good thing.”

He added: “There’s a special bond that combat-wounded vets have—it’s sort of a blood thing that we all share. It’s real. It’s a brotherhood.”

While it’s important to honor the troops killed in action, “don’t forget the guys that are wounded,” Greenlaw urges. “We’re not cut by razor blades; we’re cut by jagged shrapnel and bullets. It’s a rough business—real rough.”

When he speaks to groups, the MOPH national commander makes sure people understand what the survivors of a war have gone through.

“I talk about the reality of war, what it’s like to be on the ground,” he said. “I was an infantry officer. I talk about what goes on in real war. I tell people what it’s really like to be a grunt, a leg, a gravel grinder, a ground pounder.”

Journalist and historian Marc Leepson’s latest book is Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Army Sgt. Barry Sadler. He was drafted into the U.S. Army and served in Vietnam in 1967-68 with the 527th Personnel Service Company in Qui Nhon. He is arts editor, columnist and senior writer for The VVA Veteran, the magazine published by Vietnam Veterans of America.