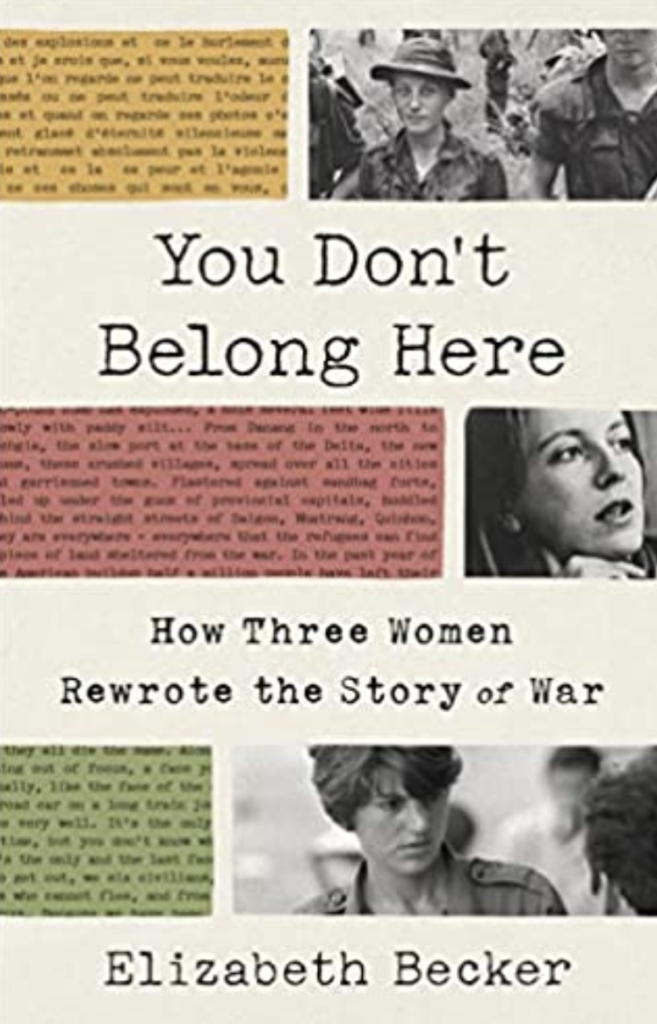

Popular histories of Vietnam War journalism tend to focus on the male war correspondents. While many newsmen on the front lines have been praised to the skies, their female colleagues remain overlooked. In her informative and well-written book “You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War,” journalist and historian Elizabeth Becker notes that not a single published work by a female war correspondent appeared on a recommended reading list accompanying Ken Burns’ acclaimed 2017 PBS documentary, “The Vietnam War.”

That silence is an injustice that Becker corrects exploring the lives and legacies of Catherine Leroy of France, Frances FitzGerald of the United States and Kate Webb of Australia. These adventurous, intelligent and compassionate women went into the war zone with curiosity and courage.

They redefined the role of women in war reporting, made groundbreaking achievements and suffered as a result of their dedication to their profession.

A Double Standard

One of the most prevalent affronts faced by these journalists was male chauvinism. Some men became extra competitive toward female colleagues — viewing them as rivals, obstacles or objects of sexual conquest.

“What the hell would I want a girl for?” United Press International’s Saigon bureau chief rudely exclaimed in front of his staff when Webb, a seasoned reporter, applied for a job, according to the book. Leroy had earned paratrooper jump wings, yet was denigrated for her small size, clothing style and assertive manner. FitzGerald, brilliant and well-educated, was interrupted and coldly cut down by male journalists when she expressed her opinions during conversations. Becker skillfully exposes a pervasive pattern of hypocrisy and a double standard that condoned brothel romps by the male press corps yet reproached women journalists for casual flings or love affairs.

Sexism also manifested itself in more subtle ways. FitzGerald’s editors were unduly critical of her writing as she prepared her award-winning 1972 book “Fire in the Lake” for publication. Becker writes that FitzGerald’s boyfriend at that time, author Alan Lelchuk, was “appalled by their harshness,” saying: “She is extremely smart and wrote beautiful prose. But she would get these nasty notes from her editors and didn’t know if she was doing well … When she got hammered, I would say they’re wrong … without proclaiming she’s a woman and she can’t do this, they wrote to her in a way they wouldn’t write to a man.”

Neither the book nor the women profiled in it should be accused of being anti-male. Interwoven with the story of the trio are men who supported their endeavors. Lelchuk took FitzGerald under his wing. A battle-hardened former French paratrooper believed in Leroy and taught her to parachute jump, opening up new opportunities for her.

“The Soldiers Are My Friends”

Webb bobbed her hair and wore combat fatigues, scorning comforts so that she could endure the same deprivations as the men while writing about them.

“My pencil wobbles as I write the story of two young helicopter gunners I knew briefly as Smitty and Mac,” Webb wrote in a piece called “Life and Death of a Helicopter Crew,” described in the book. “I saw them go to war many times. Now I have seen their bodies come back and that is why this is a hard story for me.”

It is those stories of lionhearted comradeship with soldiers that are most appreciated by this reviewer, who was particularly touched by the story of Leroy. Especially moving are her words to French writer Marcel Gugliaris in Saigon when he asked why she chose her career.

“I follow this profession out of love,” Leroy replied. “In war I have found something I never had anywhere else—a kind of fraternity, camaraderie, pure friendship of soldiers. The soldiers are my friends … I love them because I march with them, because we have memories in common, because when we meet again three months later we remember the operations … where so much went on, the most incredible, the saddest, but memories that have become wondrous. We remember the good side, the heroics.”

Becker offers a deeply personal look at all three, discussing their character, weaknesses and strengths, idiosyncrasies and reporting styles.

The war haunted each of them to some degree. Nightmares, hidden traumas and lack of acceptance from an aloof and critical society contributed to a sense of isolation and inner torment. When Leroy returned to Paris’ Left Bank district of writers and artists, her “liberal friends sounded self-righteous and parochial” when discussing Vietnam in her presence. She found solace among veterans’ groups.

DEstroying Stereotypes

During an era when society largely evaluated women not for their capabilities but for perceived levels of “femininity,” these journalists exuded a type of femininity that was as bold and fierce as it was naturally graceful. Leroy parachuted in her blonde pigtails to take some of the most acclaimed photos of the war and was wounded by mortar fire. Webb was embedded with the South Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division, covered street fighting and survived capture by communist guerrillas in Cambodia in 1971. FitzGerald matched wits with war analysts then perceived as “the best and brightest.” The women were not out to prove anything. They were in environments they wished to be in and simply did their best.

Without the contributions of intrepid reporters like Leroy, FitzGerald and Webb, much of the Vietnam War’s history, including the images and stories of individual troops, would have been lost. You Don’t Belong Here is a testament to the fact that war stories deserve to be told and that both men and women deserve the chance to tell them.

You Don’t Belong Here

How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War

by Elizabeth Becker, PublicAffairs, 2022

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.