‘Emily, the Yellow Rose, confounds the boundaries between history, legend and myth as do few other figures in American folklore’

Her name may have been Emily D. West or Emily Morgan. She has become, in popular culture over the past 175 years, the “Yellow Rose of Texas.” Whatever her actual last name, Emily may have had nothing to do with the events associated with her—if she ever even existed. Regardless, Emily West/Morgan remains the mystery woman of old-time Texas, and Lone Star State folklore would be poorer in romance without her.

History purports to offer a straightforward presentation of unvarnished facts. We “know,” for example, that David Crockett, another notable hero of the Texas Revolution, was born on a mountaintop in Tennessee on August 17, 1786. If only it were that simple. Though now part of the Volunteer State, the district in which his father John Crockett’s log home stood was then a part of North Carolina. Davy did die 50 years later at the Alamo, on March 6, 1836. Yet diaries of Mexican soldiers imply the “Lion of the West” may not have gone down swinging his rifle “Old Betsy” like a mighty war club as legend would have it. Revisionist historians argue that Crockett, along with five other men, surrendered as dawn broke over the mission/fort and were executed by firing squad. How preferable, though, to picture Davy as Fess Parker portrayed him for Walt Disney—rugged face blending into the Texas flag a split second before Mexican bayonets claim his life during a heroic to-the-last-man stand.

Since history isn’t necessarily set in cement, people sometimes opt for a preferable if less than precise rendering of the past. In a word, legend: events and behavior not as they were but as they should have been. Myth, which presents larger-than-life characters not derived from people living or dead, also gets added to the mix. Mythical figures—such as Paul Bunyan, the colossal lumberjack, or Pecos Bill, the superhuman cowboy—are “created truths” that convey the essence of a land and its people. Crockett, like many other fact-based heroes, has come down to us as part history, part legend. Emily, the Yellow Rose, proves more difficult to pin down. She confounds boundaries between history, legend and myth as do few other figures in American folklore.

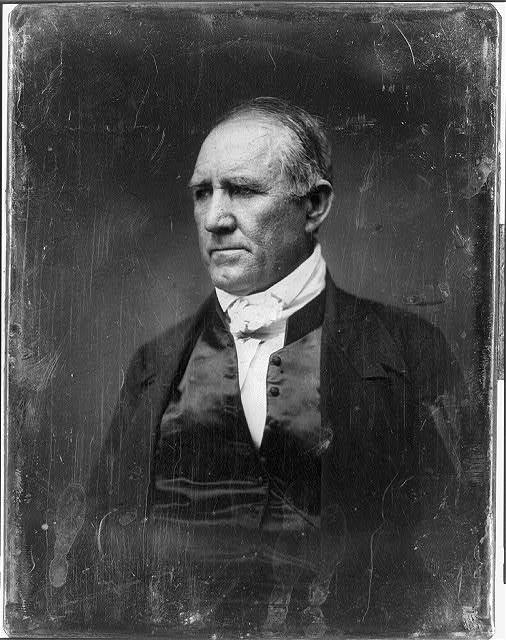

It’s not difficult to find “experts” who insist Emily is a fictional creation. On a recent visit to the Alamo, a tourist from New York asked an attendant about her. Emily Morgan? Pure fabrication, the host assured his guest, adding that this was far from the first time he’d had to set the record straight. Others disagree, insisting that an African-American woman appeared at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. On that date Texian General Sam Houston and his ragtag army defeated Mexican tyrant Antonio López de Santa Anna and the advance element of his army. Houston and about 900 volunteers had been steadily withdrawing eastward toward Louisiana, closely followed by Santa Anna with more than 1,300 men. At siesta time on the 21st, Houston’s force attacked without warning. The fight lasted 18 minutes. When it was over, 700 Mexican troops lay dead, with most of the rest wounded and/or captured. The Texians suffered just nine fatalities. Houston’s strategy of feigning retreat while readying for a decisive strike clearly evinced his military genius. Yet some historians argue the actions of a single woman made possible the victory that ensured Texas’ independence from

Mexico.

First to put this notion into print was English ethnologist William Bollaert (1807–76). Arriving in Galveston in 1842, Bollaert toured the Republic of Texas for two years. On July 7, 1842, Bollaert scribbled in his diary:

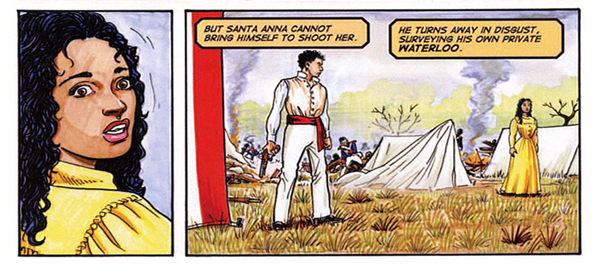

The battle of San Jacinto was probably lost to the Mexicans owing to the influence of a mulatta [sic] girl belonging to Colonel [James] Morgan who was closeted in the tent with G’l Santana [sic] at the time when the cry was made, ‘The enemy! They come! They come!’ and detained Santana so long that order could not be restored again.

Significantly, Bollaert failed to note either the girl’s name or from whom he picked up this fascinating nugget. Just as cowboys regaled gullible dudes with tall tales of prowess on the prairie, Bollaert perhaps was taken in by some inspired yarn-spinner. Several historians do accept him at face value. Michael L. Tate insists the diary “remains one of the most important sources of information on the Republic of Texas and its people.” Though it has long been argued that Bollaert got his information straight from Morgan, the mulatto girl’s ostensible owner, historian James E. Crisp hints in his 2004 book Sleuthing the Alamo that Bollaert may have heard about the mulatto girl from none other than Sam Houston—a possibility unearthed in 1996 by scholar James Lutzweiler when he thoroughly researched Houston’s letters.

Even if (for many observers, a big if) Bollaert did get his information from Houston—the former general, then president of the Texas Republic and, after Texas became a state in 1845, governor (1859–61)—that doesn’t conclusively prove that a mulatto woman played such a decisive role. Houston, according to biographers, told more than one whopper in his time. Why, though, would he fabricate such an unusual story?

Significantly, Bollaert’s visit preceded the Mexican War (1846–48) by two years. With devoted Jacksonian John Tyler the sitting U.S. president, few in the know doubted armed conflict would erupt. After nearly a decade as an independent republic, Texas would likely make the transition to statehood. In doubt only was whether the latest state would be slave or free. Many of the earliest settlers had arrived from the North, and the 1824 Mexican Republic had outlawed slavery. Those settlers who did bring slaves to the region appear to have been content changing their status to “indentured servants,” a semantic alteration that sidestepped the stigma of ownership. Noteworthy, however, is that a large influx of Southern immigrants did not occur until after the Texas Revolution.

Houston himself is known to have been a civil rights advocate, most overtly for the Cherokee Nation. Various episodes suggest he did not think highly of slavery. In 1840, after Deep South immigrants had come to dominate the new republic, the Texas Congress passed a law dictating that all free blacks must leave Texas; President Houston issued a reprieve the following year. (Two decades later, on the cusp of the American Civil War, then-Governor Houston refused to pledge his loyalty to the Confederacy and was ejected from office.) With statehood on the horizon in the early ’40s, Houston might have concocted the story of a courageous mulatto in hopes that budding-scribe Bollaert would spread the tale and that such a heroine (albeit manufactured) might convince fellow Texians that theirs was, and should remain, a multicultural land.

Sam Houston might have drawn from the Bible, a volume he knew well, for his tale. In the Apocryphal Book of Judith, the beautiful namesake Jewish heroine beguiles enemy general Holofernes, then slips into his chamber to behead him in his sleep, thus encouraging her people in a coming battle. The story suggests that women could harness their physical allure for the greater good and that those who did so ought not to be regarded as temptresses but as heroines. The end justifies the means. Might then a mulatto woman, real or imagined, do the same for a modern-day Promised Land called Texas? If she existed, Emily cut off Santa Anna’s head only figuratively. Houston may have toned down the tale to render it more believable to his contemporary audience.

If Houston did concoct the story for the good of Texas, the irony is that Bollaert failed to spread it. Though he would publish widely on his return to London, the man wrote little about the Lone Star State. When he did, Bollaert remained mute as to his most intriguing discovery. Upon Bollaert’s death, his family inherited his writings. In 1902 collector Edward E. Ayer purchased the eight volumes of notes about his trip (six diaries, two journals). Nine years later Ayer turned them over to Chicago’s Newberry Library. There they sat, mostly gathering dust, occasionally consulted by some Texas historian interested in the early days—that is, until 1956. A sudden rash of Alamo movies and simultaneous resurgence in popularity of the old folk song “The Yellow Rose of Texas” had stirred up a fascination with Lone Star State history. That year editors W. Eugene Hollon and Ruth Lapham Butler sought out Bollaert’s diaries and published them under the title William Bollaert’s Texas, a book that would prove extraordinarily popular.

One reader was Henderson Shuffler, a former journalist who had accepted a job as publicist for Texas A&M University. Among his tasks was the renewing of interest in Lone Star heritage, and he took this task to heart. If not altogether diligent when it came to the facts, Shuffler threw himself energetically into his work, embarking on a speaking tour. Asked to give a talk at the San Jacinto Monument, Shuffler accepted. Learning that Houstonites were very much intrigued by “The Yellow Rose” ballad and the legend of a mulatto beauty, an inspired Shuffler suggested the girl in Santa Anna’s tent was “a fitting candidate” for the identity of the woman in the tune. (Despite the widespread notion that this story harks back to old-time Texas, there is not one whit of evidence to suggest, much less prove, the two had ever been linked prior to the speech; though when his assertion later came under attack, Shuffler himself insisted, “Her story was widely known and often retold.”)

His speech went over wonderfully, so Shuffler kept this tidbit in his repertoire of yarns passed along as bona fide facts. Apparently, he also grew ever more salacious in his description of the seduction, telling gullible crowds the lovely Yellow Rose had given herself to Texas “piece by piece,” a phrase that elicited knowing chuckles. At one point, now seemingly believing his own hokum, Shuffler went so far as to assert that a special monument ought to be erected at San Jacinto to that woman who “gave her all” (more salacious laughter). Among those fascinated by Shuffler’s version of events was Martha Anne Turner, an English professor at Sam Houston State University.

Thrilled by the tale, Turner set off to do some research and creative/imaginative thinking. At the 1969 annual conference of the American Studies Association of Texas, this scholar of literature, not history, presented a paper that would forever alter public perception, creating a mulatto heroine who grew more beautiful with each retelling. Turner convinced attendees the as-yet-nameless woman in the song had to be the “mulatta [sic] girl” mentioned in Bollaert’s journal.

From that moment the beauty of San Jacinto and the Yellow Rose of Texas were “collapsed” into a single person. Whether that had been the case in actuality, the idea at once assumed the status of mythic truth. Turner reasserted her claim in her 1975 book The Yellow Rose of Texas: Her Saga and Her Song. As people tend to believe what they read, particularly if written by a scholar, the die was cast. In truth, Turner’s admittedly delightful volume has more in common with Homer than Herodotus. To quote a character in John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Turner did precisely that.

In his 1985 historical novel Texas, James Michener notes that on the eve of battle, “a beautiful mulatto slave girl named Emily from the Morgan plantation…was delighted at the prospect of spending yet another siesta with the general.” With a single phrase Michener reduced our heroine to a whore. Texans of a liberal-progressive bent sided with Holly Beachley Brear, who in her 1995 book Inherit the Alamo: Myth and Ritual at an American Shrine labeled Michener’s approach “creation mythology.” Conservative men, Brear argued, did not want the battlefield achievement of white males dissipated by a remarkable woman; better to diminish the “dusky quadroon” to an eager prostitute rather than enshrine her as a patriotic sexual predator, Texas’ original “cougar.”

Historian Margaret Swett Henson puts factual likelihood above feminist positioning, arguing that the elusive woman had been seized from Morgan’s plantation some days before the battle, and was thus neither whore nor predator. Henson, noting the problematic geography and following a cautious timeline, notes in The Handbook of Texas that the girl at San Jacinto “could not have known Houston’s plans, nor could she have intentionally delayed Santa Anna.” Henson does not preclude the girl’s being “in Santa Anna’s tent,” but neither does she deny that such a dalliance, however accidental, may have had precisely the impact those who lionize the young woman identified by Michener as “Emily” love to claim.

Now, though, another piece of the puzzle emerges. From where did Michener get the girl’s name and that of her owner? By then, Texas historians had more or less taken for granted she was named “Emily.” But her identity, her origins and her surname all remain up for grabs. In 1996 Lee Paul claimed that an indentured servant, Emily D. West, had been born in Albany, N.Y. This contradicted earlier accounts that the slave Emily Morgan had entered Texas by way of Louisiana, her birthplace either Boston or Bermuda. Today many believe Emily hailed from New Haven, Conn. A few argue that the confusion over names suggests there might have been two different women, each named Emily.

As to whether Emily, if she existed, can be placed at San Jacinto on the eve of battle, this much is hard, cold fact: A bond-servant contract, dated October 23, 1835, discovered in New York City some years ago and now filed in the University of Texas, Arlington, Special Collections unit. This paper clearly states that a free black woman, living in the Northeast and named Emily D. West, agreed to travel to Texas. Upon arrival Emily would serve as housekeeper for James Morgan, a businessman and colonel of the Gonzales volunteers. While this firmly locates an “Emily” at the right time and, generally speaking, the right place (Texas), in no way does it imply that she was ever at San Jacinto, much less that she spent the night in Santa Anna’s tent. Even so, a private in Houston’s army is known to have, with a wink, whispered after the battle that one reason for Houston’s victory had been Santa Anna’s “voluptuousness.”

As for Emily’s contract, her term of servitude stated she would remain in Morgan’s employ for one year. Yet another document reveals that a woman of the same name, planning to travel from Texas to the States shortly after the fight, filed for legal travel papers, claiming to have lost hers at San Jacinto. Isaac Moreland, the commander of Houston’s artillery unit (two ancient cannons nicknamed the “Twin Sisters”), bore witness he had seen Emily Morgan on the field. On the strength of Moreland’s testimony, Emily received her requested documents and traveled north. That statement, in conjunction with Bollaert’s claims, provides enough evidence for some observers that the girl Emily did indeed save Texas via a single sensual night.

A more recent theory, one rife with possibilities for drama and intrigue, is that while an “Emily” did visit Santa Anna, her last name was neither Morgan nor West. This lady was white, not mulatto; highborn, hardly a servant. This hypothesis holds that while traveling from the States to the port of Galveston aboard James Morgan’s schooner Flash, the servant Emily came in contact with the esteemed de Zavala family. Patriarch Lorenzo de Zavala, a Mexican democrat, despised Santa Anna’s tyrannical politics. De Zavala would join the Texians’ cause and later serve as the republic’s first vice president. With him were his wife (intriguingly also named Emily), three children (two from her previous marriage) and one (white, likely Irish) servant.

Now, then, we must deal with the fascinating if bothersome concept of the two Emilys “accidentally” meeting and becoming friends, as well as the further coincidence that de Zavala and Morgan were financial partners. While possible, such circumstantial speculation strains credulity. So does the next revelation: Emily de Zavala’s maiden name was West. The latest theory holds that, on the eve of battle, elegant Emily West de Zavala concocted a clever scheme: Knowing Santa Anna well, and that the would-be ladies’ man considered her attractive, she sought passage into his tent. This lady was also aware Santa Anna had become addicted to opium. With his stash of drugs and her sexual largesse, Emily so reduced the general to rubble that he could not assume command the next day. However wonderful for her beloved Texas, to admit this openly would have been an intolerable disgrace for a respectable married lady. Her secret mission accomplished, de Zavala then persuaded a slave or servant of her husband’s partner, Morgan, to claim responsibility. Thus Texas was saved, along with Emily de Zavala’s reputation. Some argue this hypothesis is racially motivated, set forth by people uncomfortable with the notion of a black heroine ultimately being responsible for the liberation of Texas: If a woman did this man-sized job, then, damn it, she must’ve been a white woman.

As for the mulatto servant Emily, she was likely well paid, which explains why Morgan allowed her to leave Texas before her year of indenture was up and also how she was able to pay for her return passage to New York, once again aboard Flash. Perhaps this version of events, however convoluted, makes the most sense.

Incredibly, though, an even more recent theory has arisen to confound and confuse, intrigue and perhaps obsess us. History records that Emily West de Zavala, following her husband’s sudden death in late 1836, also left Texas at that time—aboard Flash bound for—where else?—New York. What if, Denise McVea argues in Making Myth of Emily (2006), the slave/servant Emily never existed, as the naysayers have always insisted? There is virtually nothing to be found about de Zavala’s beloved bride before they met and married during his residence in New York for business purposes in 1830. Might not his Emily have been of mixed blood? Such a match would have created problems for so prestigious a man in racially torn Texas.

As this hypothesis goes, de Zavala and his bride (who may have actually been named “Miranda”) conspired to create a character they called “Emily.” According to this incredible if irresistible scenario, during the voyage Lorenzo passed off the Irish servant as his bride, introducing his actual wife as a light-skinned slave. If this were so, then it was Miranda West de Zavala who saved Texas on a long-ago April eve, reviving her earlier masquerade as the fictional character “Emily Morgan” at Houston’s urging. Everything that followed had been a cover-up of mythic proportions, if this potential scandal were motivated by a notably more admirable desire: not to self-servingly achieve political power for the conspirators but to protect a courageous and self-sacrificing lady.

Perhaps, then, Emily D. Morgan was but a shadow. Or, in McVea’s words, the “alter ego for Emily West de Zavala.” Linda Kirkpatrick asks on Texas Escapes online magazine: “Were there actually two women with similar names, close to the same age, going to the same place on Flash, or was there just one woman trying very hard to protect her identity?” Finally, does this lead us closer to finally discovering the truth or only draw us further into the realm of fiction?

Undeniably, each successive claim as to the identity of Emily (aka the “Yellow Rose of Texas”) adds to her mystique. The intrigue of Texas’ “dusky beauty” casts its spell—whether in the end that elusive woman who has seduced generations of willing and adoring victims, even as she once supposedly did Santa Anna, constitutes history, legend or myth. Or, more likely, some utterly and appealingly unknowable combination of the three.

San Antonio–based author Douglas Brode teaches at Our Lady of the Lake University and the University of Texas. He has written 37 books, including the recent graphic novel Yellow Rose of Texas: The Myth of Emily Morgan, illustrated by Joe Orsak and published by McFarland & Co. of Jefferson, N.C.