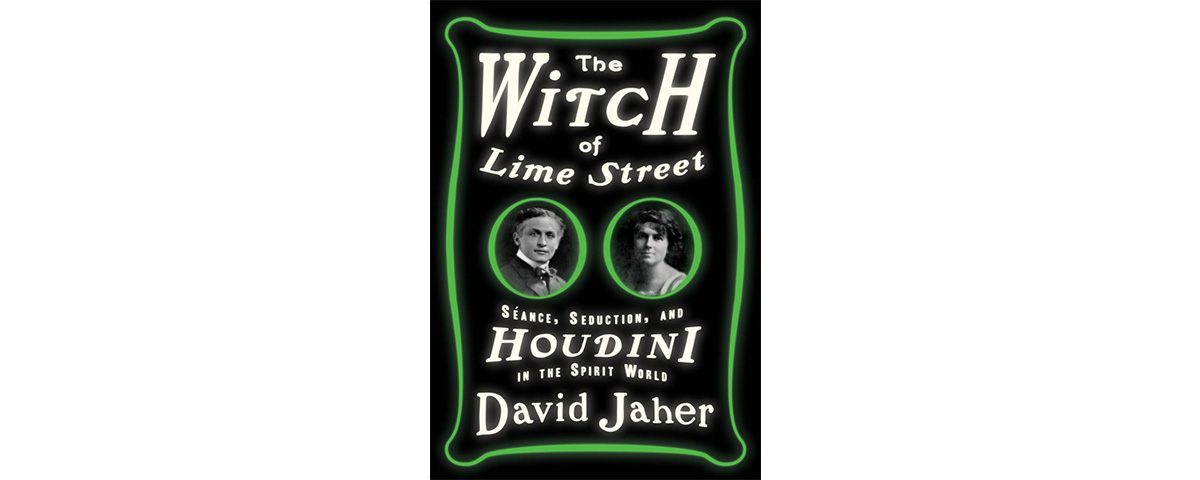

The Witch of Lime Street: Seance, Seduction and Houdini in the Spirit World by David Jaher (Crown Publishers)

NEARLY 100 YEARS AGO, America was gripped by occult fever. The vast death toll from the Great War had sparked a mainstream spiritualism craze. A raft of psychics and spirit mediums popped up to offer their peculiar form of comfort to the bereaved. They claimed to inhabit, as David Jaher writes in The Witch of Lime Street, the gauzy “borderland where the living and dead might mingle.” Clairvoyants claimed they could communicate with the deceased through séances, Ouija boards and automatic writing. Eminent men debated the idea of immortality, some giving credence to flimflammers.

Jaher details the fascinating battle of wills that occurred in 1923 when Scientific American created a contest to determine if there were any authentic mediums in the country. It offered two $2,500 prizes to the first people to produce visible physical manifestations emanating from the dead. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the logical Sherlock Holmes, had persuaded the magazine to launch the investigation. He’d lost an Army son to the flu, believed in spirit mediumship, promoted it on speaking tours in America and wanted it to be validated scientifically. Scientific American recruited a group of reputable men, some of them scientists, to assess the contestants. After dismissing a few obvious quacks, the judges became split over a bewitching Boston medium known as Margery. She was popular and convincing and seemed destined to win the prize until escape artist Harry Houdini stepped forward to assess her supernatural talents. Margery (Mina Le Roi Crandon) wasn’t a typical medium. Married to a professor of surgery at Harvard, she was a youthful blonde—attractive and flirtatious. She’d attended a couple of séances, out of curiosity, and then became a medium herself—channeling her late brother, Walter. At her Boston home, she mesmerized séance participants with brash commentary from Walter. Tables moved, a bell rang, the piano played—all in the dark that mediums conveniently required. Then, Margery started producing “ectoplasm,” ghostly essence that supposedly originated in her nether region. Astoundingly, the judges spent seven months studying her. She was escorted to Harvard for séance sessions; photographs were taken. Meanwhile, she had a fling with one of the judges, and the man supervising the contest, Scientific American managing editor Malcolm Bird, was so smitten that he lobbied the judges on her behalf.

It was left to Houdini to bring some sense to the deliberations. He was an expert on illusions and tricks and had flirted with the occult himself, trying futilely to contact his beloved mother. Houdini observed Margery at one séance, then built a special “spirit cabinet,” what he called a “fraud preventer,” for her to sit in at a second. It limited her movement, and nothing happened at that séance. Houdini determined that Margery was merely very good at using her arms, legs and feet in the dark to create effects. (The “ectoplasm” was animal intestines.) Swayed by Houdini, the judges denied her the prize, sparking a dispute between Houdini and Crandon’s husband, Bird and Doyle. Houdini, disgusted by charlatans, began a crusade against quacks and started demonstrating Margery’s tricks at his shows. Jaher’s research is impressive but he devotes too much space to things that go bump in the night. In the end, we learn that facts don’t dissuade those determined to believe—and that beauty and sexual allure can cloud the judgment of even those paid to separate fact from fiction. Houdini, master showman, was the exception.

Richard Ernsberger Jr.