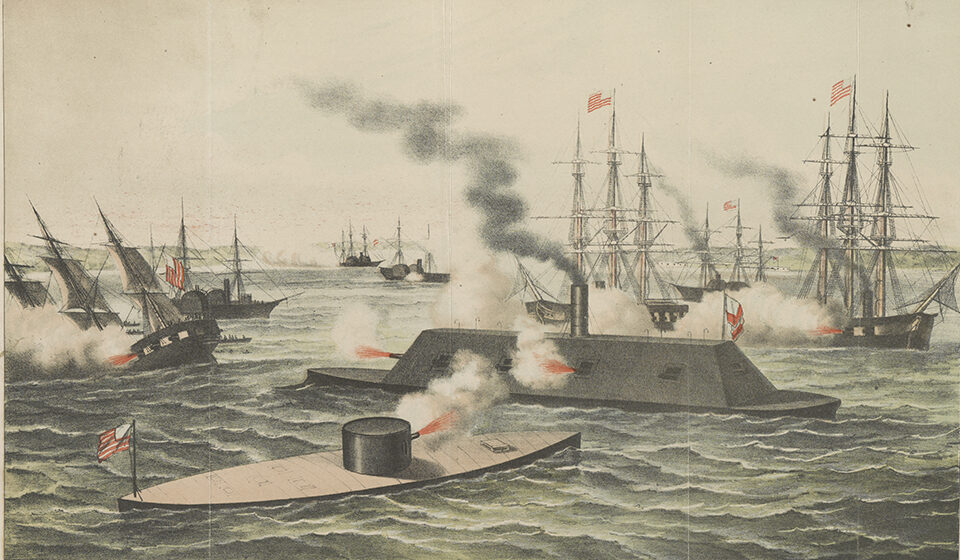

George M. Newton, a sailor aboard USS Minnesota, had a spectacular and dangerous view of the revolutionary Battle of Hampton Roads on March 8-9, 1862, which pitted CSS Virginia against USS Monitor. His vessel was one of the three Union blockaders Virginia set its sights on the morning of the 8th, and it was the only one to survive. Newton watched as Virginia—constructed in Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Va., upon the iron hull of the former USS Merrimac—rammed and destroyed Cumberland, and then set Congress ablaze and forced it to surrender. That night, as Congress’ flames illuminated the Roads, Newton saw Monitor arrive to contest the Confederate ironclad. His vivid letter recounting the seminal two-day engagement is a rare find in 2019.

GEORGE M. NEWTON was born in Grafton, Mass., on October 14, 1839. A brick mason who stood 5-foot-10½-inches tall with a fair complexion, blue eyes, and brown hair, Newton enlisted in the U.S. Navy on April 11, 1861, to serve aboard Minnesota. That same day he sent a letter to his parents, telling them, “I had made up my mind at the first talk of war that I should go south Ether as a volanter or on board a man of war knowing or thinking that they would call for Volanteres for they have in others States I concluted that I had rather go on the water than on land.” He shipped as a landsman, or ordinary seaman, “performing what duty they think I am best fitted for on Board.”

By summer, Newton was on duty in Hampton Roads, Va. He performed various tasks aboard Minnesota and often wrote home about the sites and events he witnessed. The landsman saw the capture of Confederate privateers, toured the burned-out ruins of Hampton, and watched the shelling of Confederate Forts Clark and Hatteras. He also witnessed escaped slaves dancing on the deck of his ship.

Beginning in October 1861, still referring to Virginia by its former name, Newton began to write of the trepidation the men felt about “the merimack a flowting battery which we expect down from the point most any time. for she has been seen at the point.” Nevertheless, he felt confident that “if she comes she will have a warm reception.” Eventually he would meet Virginia, as described in the letter below.

Following the Battle of Hampton Roads, Newton noted that Minnesota’s sailors continued keeping “a sharp lookout….for the meramack,” but felt fortunate they never again had to engage the Rebel ironclad. When Monitor sank during a storm on December 31, 1862, he lamented the loss of “our old friend.” In the summer of 1863, Newton and Minnesota went south to Wilmington, N.C., where he penned a wonderful account of chasing blockade runners.

Life aboard a blockading vessel, however, could be tedious. “I would like to have my discharge so as to be on shore this winter,” he told his mother in September 1863. “I would like to be eating some apples and some of your pies. [W]e have a new supply of bread on board now. the old being condemned. there was danger of it walking overboard.”

Throughout his enlistment, Newton put his duty to country above his personal desires. He hoped the Union Army would advance so that there “will be an end to secesh and peace once more reign over this country. (I hope). I have no wish to go home till this is settled, then I want my discharge, and then go home to be with you all.” Indeed, despite his strong wish to see his family, he wanted to be part of the action. “I do not want to go home till this trouble is over,” he wrote his sister in April 1862. “[I]f I could get my discharge I would join Gen Mac’s army at yorktown.”

Throughout his naval service, Newton continued to contemplate joining a unit on land. In the summer of 1863, he wrote his family, “I would like to be at home to work on the block, but I would not be contented if I was there, if I was out of the Navy I would join the Cavaly…” In March 1864, he reiterated these sentiments, telling his sister and brother, “I have not made my mind yet wheather to enter the Cavaly servise or to go to Idaho amongst the Gold.”

When Newton mustered out of the Navy at Baltimore in April 1864, he decided to join the Union Army. On August 15, 1864, now 24 years old, Newton enlisted as a private in Company F, 1st Battalion Massachusetts Heavy Artillery. Two months later, on October 25, he was promoted to corporal. Although his military service record does not specify, he likely spent the following months participating in the Siege of Petersburg.

After hostilities ended, Newton mustered out on June 28, 1865, and on July 3 was honorably discharged at Fort Warren, which defended Boston Harbor. He spent the remainder of his life working as a mason in Grafton, with the exception of two years he spent “in the west,” either in Montana or Wyoming. He died on March 1, 1921, at the age of 81.

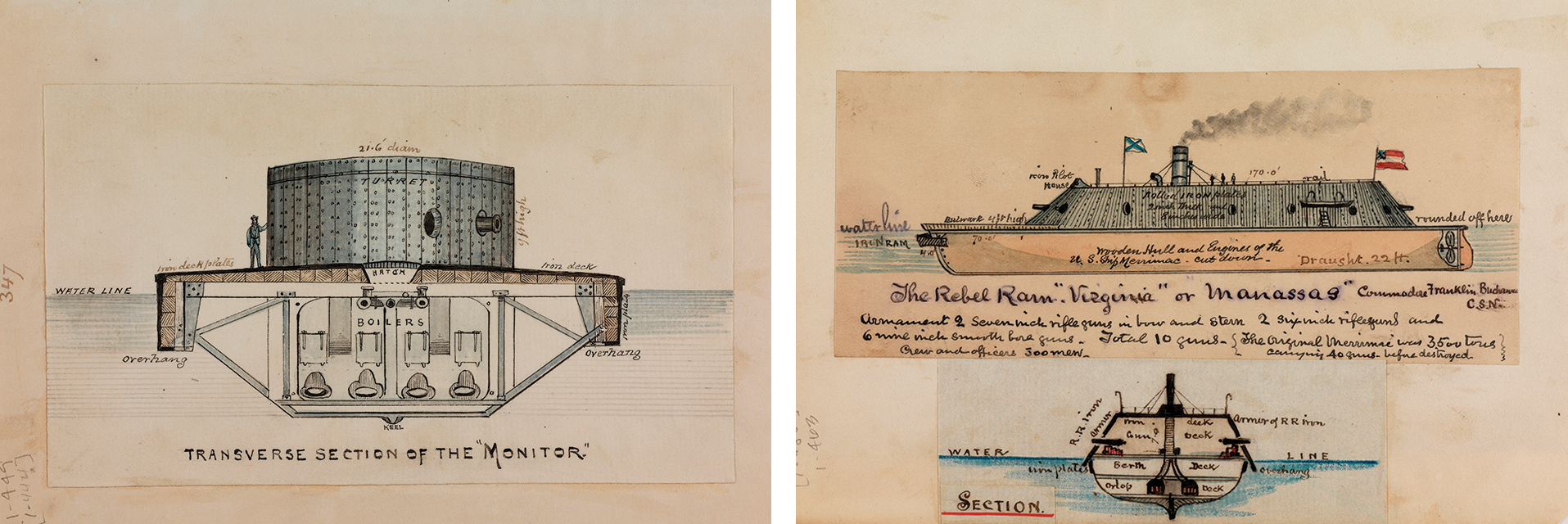

In 2018, The Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va., acquired a long-held private collection of 34 letters he wrote while a sailor aboard Minnesota. Newton’s March 11 letter, published here for the first time, is one of the most remarkable accounts ever to come to light of the famous fight at Hampton Roads. Some punctuation has been added or deleted, and paragraph breaks have been added. Newton’s vernacular spelling remains, with the exception of capitalizing the first word of each paragraph and correcting his habitual misspelling of “off.” Stricken words have been replaced with ellipses. He uses “meramack” or “merimack” when he mentions CSS Virginia, and also interchangeably uses Monitor and “erricerson battery”—a reference to the turreted ironclad’s inventor, John Ericsson—when he mentions the Union vessel that fought Virginia to a standstill.

Hampton Roads Va

March 11

Dear Father and mother and the rest of the folks,

I thought I would drop you a few lines to let you know that I was alive, and not even wounded. I suppose you have heard that we have had a fight. I will give you a short account of it, there is so much work to be done, that I have not time to write much. Saturday, at one O clock

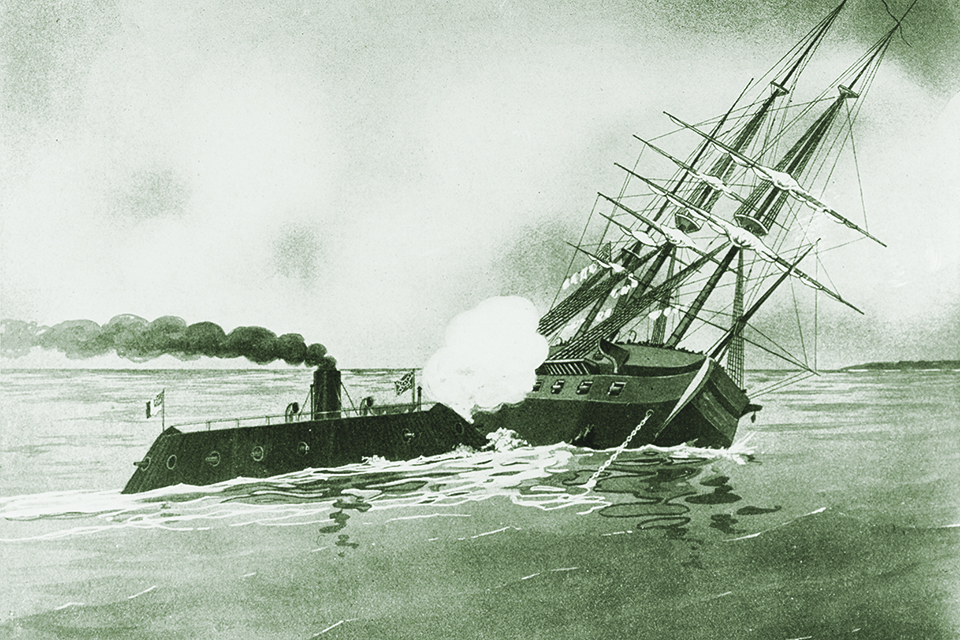

three rebel steamers, came around the point, and started for Newport News, we…sliped our cable, and started for them. a tugboat went along-side of the Roanoake and took her in tow, when we came in range of the rebel battery’s at sewells point, they opened upon us. we returned the compliment. our shots most all fell short. they had rifle Guns, one of there shot’s struck our main mast, and made an ugly hole in her. when about two miles from newport news, and under a full head of steam, we went aground, about the same time, the cumberland went down the meramack run into her bow on. at the same time the cumberland let fly a whole brodside at the merama[ck] without appearing to do her any damage.

The cumberland imeadeately went down. as she went down she let fly her pivot gun, showing her spunk to the last. at the same time some of the cumberland’s men jumped on to the meramack to board her, but it was no use, her sides were just like a roof of a house, and greesed at that. the men would slide off into the water. some of the men I hear tryed to throw some shell’s into the merramack’s smoke stack so as to blow her up, but none went in. about the same time two rebel steamers came down from Richmond, and run by the battery at Newport news, and took a part in the fight. after sinking the cumberland they commenced to fire at the congress. the congress ran aground so that the rebels had it most all there own way.

The congress kept up a steady fire upon them, but it was no use. after having lost half of her men, she raised the white flag and left her—after setting her on fire. there we was trying…to free the ship, but she was fast and hard in the mud, but when we could get a chance to fire, we let fly. the rebels steamers returning the complement as soon as they finished the congress, they made for us bow on. consequently we could only use three guns to an…advantage, our pivot on the spar deck and two guns on the gun-deck that were transfered from the Broadside ports to the bridle ports. the meramack headed directly for us. our guns wer aimed well, making good shot’s….the enemy hauled off, somewhat damaged. I rec[k]oned one of there steamers, I took to be the yorktown, must have been badly damaged, with som loss of life, as our shots struck her in good shape.

Once in a while they would come in range of our broadside guns. then we would give it to them. every time that we could get a range of them, we would let fly, taking good aim. this ended the first day’s engagment. our loss in killed was three and a number of wounded some mortally. our ship was damaged somewhat, the balls, and shells, going through us, and all around and over us. the enimy hauled of I should

think about seven O clock, to commence again the next day. we stayed by our guns all night, not knowing how soon they might be upon us. as soon as they hauled off we commenced to tear down the comodore’s cabin, for to transfer a couple of guns to the stearn ports. one of the guns was mine. we was called the guard of honor. we expected the enimy would come around our stern, and rake us fore, and aft.

They troubled us none during the night. we was to work all night, trying to get the ship off. we had six or eight steamers, and tugboats,

alongside of us, doing there best to get us off, but it was no use. we put a lot of beef, and pork, on board of the steamers, to lighting us, and sent off two heavy safe’s…I suppose filled with money, and valuable papers. Sunday morning. At daylight this morning we had breakfast (if you call it breakfast) of hot coffee and hard bread, (the sun came up in big shape denoting a good day). I forget to mention that last night about ten O clock the erricerson battery came to our releaf a querr looking object she was. you had better believe that we was glad to see it, for we were all bound not to be taken prisoners.

Our captain sung out to the Officer of the erricerson and says I am glad to see you….the officer of the battery made answer. I think some one else will be to morrow; (meaning the merramack). the burning of the congress last night was a handsome sight. about midnight her forward magazine blew up the handsomeist sight that I ever see the air was filled with combustable matter. dont tell me ever again about fire-works. the Roanoake got aground, but soon got off, and then left us for the roads again. the st Lawrance came up to our help towards night, and fired at the yorktown. then she went back to the roads, leaving us all alone, till the battery came up to our assistance. about 8 O clock this morning the rebels fired…a gun for a signal to advance.

Our ship layed broadside on….they was comeing (they advanced causiously, trying to make out what that round tower on a raft was, I suppose) the steamers were loaded with troops, the calculations being to board us, about nine the merramack let fly at us, then the erricerson battery went out to meet her, then commenced what you may call a bomb proof fight. the Officer of the monitor, not having a full supply of powder, and shot, was very carefull about waisting his shots. the monitor kept steaming round, and round, the merrimack, every now, and then, giving her a shot, the merrimack returning the complement. during the fight the monitor got in range of pig point battery and paid her respects to that battery. she then hauled off, to along distance, when she observed the yorktown and Jamestown heading for us so as to take us astern she immediately made for them. when they put back, and stayed back the rest of the day but not before the monitor had given them a few shots. the merrimack then got in range of our guns, when we opened upon her, she returning the same.

About three O clock she took to her heels and left, her parting shot went through us close to the water line, and through the shell room, and up through the deck. the water commenced to rush in, when our Captain told the men to get there bag’s and hammocks, and put them aboard of the tugs, alongside of us, and jumped aboard ourselves after taking everything that we could carry away of any value. we took all of our firearms with us. finerly the leak was stop’ed and all hands went aboard again, excepting those aboard of the white hall, which steamer had pushed off. we then commenced to throw our spar deck foward guns overboard to lighting the ship. we throwed overboard eight of them. then the tugs and steamers (the S.R. Spaulding was one of them.)…made fast to us they succeeded in slewing us round but could not get us off. we was to work till three in the morning and finerly…got off, and started for the roads.

The second day we had no one killed outright, but some mortally wounded, and a number slightly. we are to work now putting thing’s to rights. we had ten shots come through us, and a lot of them hit us. they fell thick around us, and it is a wonder that we had no more killed, or wounded. the ericerson battery came is [in] season to save a great many lives and proberly the ship, for the rebels would never have taken this ship, for everything was ready to blow her up, if it came to that. we have a Captain that we all like, and who is afraid of…no rebel steamer that ever floated, or battery. he is every inch a man. I wish I could say as much of our 1st Luit. but I can of our 2nd. a coward I despise.

The asst. sec. of the navy Mr [Gustavus Vasa] Fox came on board of us, after the merramack hauled off. he came on board of us from off the monitor we shall proberly…have to go to N. york or Boston to get repared, and take on board some more guns in place of the one’s that we throwed overboard. I lost all of my clothes, excepting what is on my back. my hammock is safe, my bag of clothes were thrown on board the whitehall, and after she pushed off from us she started for fortress monroe being on fire in he[r] coal bunkers the fire was put out, as they supposed, but the fire burst out again, and about a half of the bags on board of her was burned, mine being one of them. (but I have my head still, and hands.) the congress lost about one half of her men, the number of men on board of her at the time being about 390.

The Cumberland had about 200 killed and wounded. the Cumberland and congresses crew are on board here also the R.B. Forbes crew so we are crowded somewhat. the Captain of the monitor say’s that the last shot he gave the merramack went through her at her water line. anyway she hauled off. prety well damaged. the monitor look’es like a long raft with a smokestack in the centre. the merramack look’es like a four roofed house.

There is an english man of war in here the Rineldo the Captain of her wanted to go down inside…the monitor, but it was no go, for him. he call’es the two batteries the yankee devil’s. the Roanoake starts for new york to day. we expect the steven’s battery in here every day now I must close for there is work to be done, and we are all up in arms I have given you a short account of the fight in a hurry. I have seen some bloody sight’s, one case in particular where I see a mans head flying away from his shoulders now I will bid you good bye, till I see you, or hear from you, you have my permision to have this put in the paper if you think it will pass muster. I will write more next time, if I write.

G. M. Newton.

It was our capain’s intention if we had not run aground to have run into the merramack under a full head of steam and tiped her over if he could.

Jonathan W. White is an associate professor of American Studies at Christopher Newport University, in Newport News, Va.

He is author or editor of nine books and more than 100 articles, essays, and reviews about the Civil War. His most recent book

is “Our Little Monitor”: The Greatest Invention of the Civil War, co-authored with Anna Gibson Holloway.