An Iron Brigade soldier recounts his baptism of fire at the battles of Brawner’s Farm and Second Bull Run

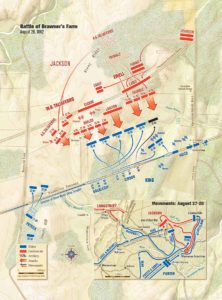

Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s report of the August 28, 1862, Battle of Brawner’s Farm during the Second Bull Run Campaign noted that the Federal regiments his men faced “maintained their ground with obstinate determination.” Four of the six Union regiments battling Jackson’s troops that day comprised a brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John Gibbon in Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s 3rd Corps of the Army of Virginia. Just weeks after their baptism of fire at Brawner’s Farm, sometimes referred to as Gainesville, those regiments from Wisconsin and Indiana that opposed Jackson became known as the Iron Brigade.

William W. Hutchins fought in one of Gibbon’s regiments at Brawner’s Farm. Hutchins, a native of Brandon, Vt., moved before the war to Prescott, Wis., where he worked as a commission merchant. Hutchins enlisted in the “Prescott Guards,” Company B, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, at Camp Randall in Madison on July 16, 1861, at the age of 27. By Brawner’s Farm, he was a corporal.

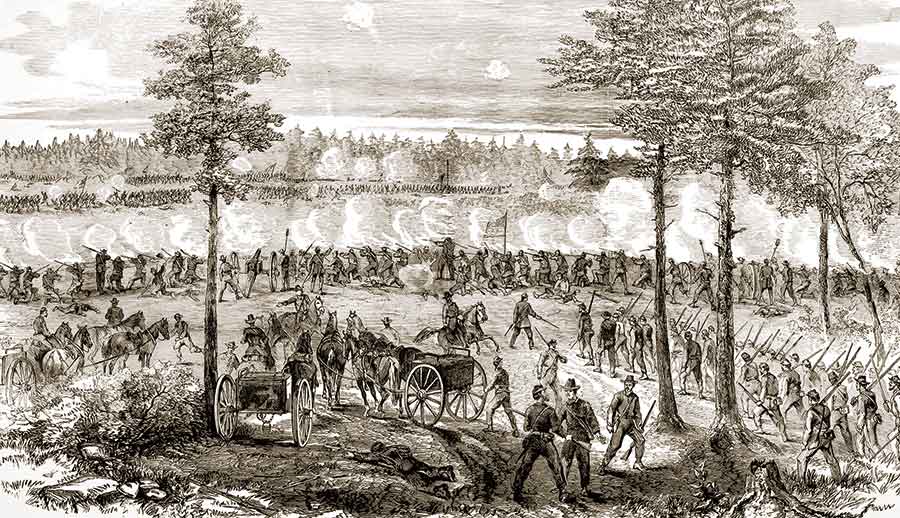

Portions of a letter about Second Bull Run written by “Willie” Hutchins to his brother appeared in their hometown newspaper, the Brandon (Vt.) Monitor, on October 10, 1862. The letter begins with Hutchins describing the 2nd Wisconsin and 19th Indiana of Gibbon’s brigade advancing north of the Warrenton Turnpike late in the day on August 28 to capture what they thought was a Confederate cavalry battery. Instead, the green Federals encountered the battle-hardened Stonewall Brigade. While the 6th Wisconsin remained under artillery fire in the Warrenton Turnpike, Gibbon’s other regiments engaged in a fierce contest with growing numbers of Confederate infantry.

The 6th, under Colonel Lysander Cutler, was the last of Gibbon’s regiments committed to the battle. After moving through the cannons of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, Cutler’s men marched down a slope toward a dry creek bed in the gathering darkness. In short order, the 500 men of the 6th encountered Confederate Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s Brigade. The two sides exchanged volleys at a distance until Stonewall ordered an advance along the Southern lines. Trimble’s Rebels charged to within 30 yards of the 6th, but Cutler’s men held their ground. After two hours of fighting, darkness and exhaustion put an end to the contest.

The 6th Wisconsin lost 72 men in the battle, fewer than the other Western Federal regiments, in part because Cutler’s men had the protection of low ground and the Confederates often overshot the blue ranks.

Gibbon’s men marched that night to nearby Manassas Junction, remaining there until the afternoon of August 29 when they returned to the First Bull Run battlefield, taking position in a Union line on Dogan Ridge. On August 30, the 6th Wisconsin and Gibbon’s brigade formed a supporting line of an attacking column under Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter hurled against Stonewall’s Confederates occupying an unfinished railroad bed.

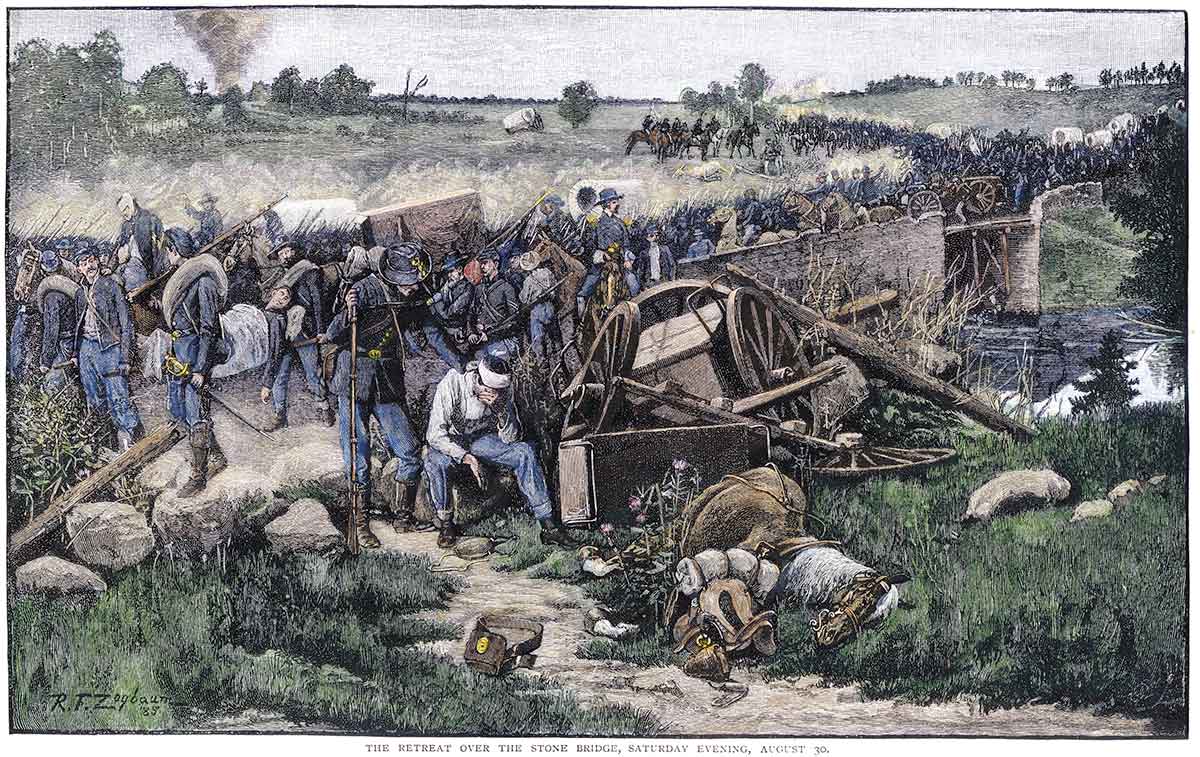

Hutchins describes the retreat of Union regiments in the front lines of Porter’s attack after they had been decimated in close fighting along the Railroad Cut. The 6th Wisconsin formed part of the rear guard following Porter’s failed attack. The Badgers’ division commander, Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday, claimed that the regiment was the “very last to retire,” marching “slowly and steadily to the rear.” Gibbon’s brigade retreated that evening from the battlefield with the balance of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s defeated Army of Virginia. “Stars for the Yankees were few” at Second Manassas, writes John Hennessy in his superb study Return to Bull Run, but among those commanders and units that performed well were John Gibbon and his Iron Brigade. Paragraph breaks have been added to Hutchins’ account to enhance readability.

Brandon Monitor, October 10, 1862

Below we have some extracts from a letter received in this village from Willie W. Hutchins, formerly of this town, now a member of the 6th Wisconsin Regiment. Though old, they are full of interest. After describing several sharp skirmishes he had engaged in (under McDowell) and which he mentions as “the harmless operation of a game of ball,” he says:

Retreating before [Stonewall] Jackson’s whole force we arrived on the 28th of August at Gain[e]sville, where signs of rebels were apparent. McDowell ordered the 2d Wisconsin and 19th Indiana forward to take a battery, our regiment and the 7th lying in the road as reserve. While here the artillery on both sides opened, and for the first time we felt the REAL thunder of battle. Shell and solid shot fell all around us or burst in the air over our heads. My own feelings were hard to express. It was the grandest sight I ever saw. Soon the rattle of musketry was heard, and the cheers of the men. Word soon came for us to go to the support of the 2d and 19th. Over the fence we sprang, and on a double quick we went in.

It was now dark, but a perfect sheet of fire could be seen from both our lines and those of the rebels. Riderless horses dashed by. Wounded men passed us, but still on we went until only a few yards intervened between us, when the rebels opened the ball with two pieces of artillery, throwing grape and canister, and our ranks commenced thinning. Our rifles spoke, and gradually their fire slackened. Pretty soon we heard the order given by the rebel officers ‘Charge bayonet– forward– double quick– march.’ We withheld (as if by instinct) our fire for a few seconds, and then gave them one volley. They had started yelling like demons, but our boys gave yell for yell, and they broke.

After that we held our ground and gave them a perfect shower of bullets for some time and retired (taking our killed and wounded with us) to the timber, a short distance in our rear, where we laid down for an hour or two, and started for Manassas, which place we reached by day-light the next day. McDowell complimented us highly for our good conduct, saying that considering the great disparity of forces engaged, it was the hardest fought engagement of the war. We fought one hour and ten minutes, and our Brigade lost nearly or quite 800 men. The 56th Pa. and 76th N.Y. regiments fought with us, and their loss was about 200 men, making the whole loss about 1000 men.

A rebel Captain who was taken prisoner asserted that they lost 1500 or 2000 men; and also said that we were opposed to the old Stonewall Brigade that never before shown their backs to the enemy. The fight, unproductive of results as it may seem; was really our salvation, as had it not occurred we should have been ignorant of the presence of so large a force of the enemy, and should inevitably have been cut off. However that may be, it taught us how to fight, and in the battles of the 29th and 30th we were shining lights. On the 29th we laid on our arms supporting a battery and dodging shell and solid shot. We supported it till noon of the 30th.

Our Division was ordered into the timber on the center for the purpose of clearing it and forcing the rebels back, and driving them from the R.R. track, behind which they had taken refuge, and poured into us a perfect hail storm of bullets. Here the N.Y. Regiments of our Division, or some of them (they all deny the soft impeachment, one N.Y. regiment laying it on another from the same State) broke and skedaddled, crying out our regiment is cut to hell, we are cut to pieces, etc. Our General who was with us ordered us to shoot the first one who attempted to break through our ranks, and even strode amongst them with a drawn sword and cocked pistol, swearing he would kill them if they did not face the music.

A few, to their credit be it spoken, fell into our ranks and stood up like men, while others contented themselves with lying down amongst us (we were lying down, while our skirmishers were feeling for the rebels) and when our attention was drawn off by another squad of cowards, they left. The skirmishers drove in the rebel sharpshooters on their reserves, and drove the reserve back on their main body, and then fell back. They reported the rebels in force behind the railroad, and in three lines (one lying down, on their knees, and one standing) of rebels waiting to receive us; and also reported the entire rout of N.Y. troops and the withdrawal of the balance of our Brigade. Our General Gibbon, who had staid [sic] with the 6th, then ordered us to fall back with our face to the enemy until we got out of the timber, and then about faced us, and we started home double-quick.

Our General rode in front of us, and when we got out of the timber he turned round saying ‘Good for the 6th. Boys, you never did better on drill,’ and proposed three cheers, which were given with a will, the shot and shell whistling about our ears funny. Our ranks were never any straighter, and the men had step perfectly. All the order we heard occasionally was ‘Guide colors,’ and ‘steady.’ We had got not more than a quarter of a mile when two rebel regiments filed around the timber and deployed into the timber to nab the whole batch of us, but ‘we wont thar.’ When we reached our battery (B of 4th Art.) we were greeted with a perfect ovation in the shape of cheers and congratulations. We then fell into position in rear of the battery as a support, where we staid amidst a perfect shower of lead till the battle dried up. Our Regt’s loss was about 50 killed and wounded, the most of which we left behind in the woods, having no means to carry them away with us.

While we were supporting the battery we laid in a splendid place to see the whole operation of the left wing of our army and the disgraceful cowardice of the N.Y. and Pa. troops. Men scared to death, fleeing in every direction, having thrown away their arms and accoutrements, and in some instances the officers throwed away their swords to expedite them in getting away. One or two lost their colors, and it got to be a common sight to see a set of colors coming out with not more than one or two men around them. As a contrast, one Brigade of Gen. [Jesse] Reno’s Division went in and came out broken up. When they got to the edge of the field the color bearers waved their colors, and almost by magic a Brigade was formed (and a good sized one, too) and went in again, and the next time they came out they came out in order.

Well, Charlie, I have been in battle and now know what a man’s feelings are. I cannot describe it. At first there was a touch of anxiety as to the result, then an unnatural feeling. I don’t know what, like to a man who has a long time thirsted for something and sees it within his reach. After that the sight of my comrades falling around me made me like to a perfect devil. Two of them were my tent mates, one shot through the head, probably mortally wounded; and the other a flesh wound in the leg. One poor fellow had his face stove up with a bullet, and two were shot through the left breast. Some in arms, and more in legs. I had one bullet go through my pants, and one landed on the bayonet of my gun. One passed between my legs and into another man’s leg; one near my head and cut the whiskers off our Captain, and my right hand man had a ramrod knocked out of his hand. I don’t thirst for more fight, although if there is to be one I am in.

Your Brother, Willie.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n the last day of February 1864, Hutchins, now a sergeant, reenlisted as a veteran volunteer and enjoyed a furlough of 35 days in his Vermont hometown. By the spring, Hutchins had fought in nine battles. During some of those engagements, he could have been excused from fighting given his assignment as a clerk, but he still served on the battle line. By the end of May, Hutchins had fought in the bloody Overland Campaign and, although only a sergeant, had command of his company.

Following actions at Petersburg in late June, Willie Hutchins received a promotion to captain on July 28, to replace Captain Rollin P. Converse, killed at the Wilderness. Rufus Dawes noted in his memoir Service With the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers that Hutchins went into battle below Petersburg in August “full of the satisfaction of his new commission.” Tragically, Hutchins died in his first engagement as captain at the Weldon Railroad on August 19, 1864. A memorial inscription to Hutchins appears on the grave of Vermont Governor Ebenezer J. Ormsbee in Pine Hill Cemetery in Brandon, Vt.

Keith S. Bohannon is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia.