Disillusioned Private Robert Beckwith longed for home and warned a friend not to enlist. He would die at 2nd Bull Run

THOUGH BORN IN CONNECTICUT and living in Pennsylvania when the war began, Robert S. Beckwith answered the call by enlisting as a private in Company D of the 1st New Jersey Infantry on May 22, 1861. The 1st was teamed with the 2nd and 3rd New Jersey, and in August joined by the 4th New Jersey to form the 1st New Jersey Brigade, which would eventually do most of its fighting with the Army of the Potomac’s 6th Corps. The son of Thomas and Sally Beckwith of Windham, Conn., Private Beckwith was 27 years old in 1861—just a tick over the average age of 26 for a Civil War soldier. He chronicled the beginning of his service in letters home to John P. Billings and his wife, Mary, who lived in what was then known as South Easton, Pa. That town is now incorporated into the larger city of Easton, just across the Delaware River from New Jersey. John Billings was a cousin of Beckwith’s sister-in-law, Minerva, married to Robert’s brother, Chester H. Beckwith. According to census records, Billings was employed as a blacksmith and “tin plate maker,” and it is possible Robert Beckwith was learning those trades from Billings when the war began. The series of letters that follow chronicle Beckwith’s early excitement about entering the Army, and his quick disillusionment with the service. Though he sees action in several battles, his letters focus on his desire to see family and friends again. He also urges Billings not to rejoin the Army when his initial three-month enlistment expires. In August 1862, Beckwith was wounded at the Second Battle of Bull Run. He died of his injuries the same day.

[hr]

New soldier Beckwith wrote this letter from Camp Olden, named for New Jersey Governor Charles Smith Olden. The camp was located south of Trenton, near the Delaware and Raritan Canal, opposite the state prison. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd New Jersey Regiments were all organized there. The regiments were soon ordered to protect vulnerable Washington, D.C. This letter was written the day before the 1st New Jersey, commanded by Colonel William R. Montgomery, took the railroad from Trenton to Washington. A comrade of Beckwith’s remembered “women screeching and screeming, waving of hankerchiefs, throwing hats and everything” as the regiments boarded their railcars. The regiments arrived in Washington at 3 a.m. on June 29, and eventually established a camp on Capitol Hill they named “Camp Monmouth,” after the state’s largest Revolutionary War battle. In the letter, Beckwith mentions his desire to see John Billings, who had enlisted in the three-month 1st Pennsylvania.

Camp Olden, June 27, 1861

Dear Friend Mary,

I now write to you a few lines for the last time on this ground for we are going away tomorrow morning. That was what news was last night. We are a going to Harpers Ferry, I suppose, by what I can hear. If I do, I shall see John P. Billings. If I do, shan’t I be happy. I shall jump ten feet into the air.

We have got our uniform. It is a blue overcoat and a blue dress coat, blue pants. Our hat is a black one about ten inches high with the brim turned up on one side with a bugle in front and a big eagle on the side and a black feather on the side—a blue cord goes around it twice with two tassels in front. It looks gay, I tell you. We are to have ten rounds of cartridges. We have got all of our equipments now [and] we are ready to fight.

I have not heard anything Emily yet. I should like to very much but as it is, I shall have to go without it. Give my love to her and tell her that I shall cat howl her when I come home.

I can’t think of much more to write. Give my love to all. I think of sending my clothes home. I don’t know whether I can or not. I will tell you before night. I shall send it to South Easton in care of E. Kline. If I send it, I shall tell you. I am going to stop now.

Now it is afternoon. We have had a Battalion drill. I am going to send my carpetbag up by Major [Lieutenant Charles] Sitgreaves. He said that he would take it up for me. I shall put 25 cents in this letter to pay the Express on it. If you get it, let me know in the next letter you write to me. I expect to see John soon. We start in the morning at 5 o’clock. Tell John if I don’t see him that he may wear the clothes that I send up. I thought that I should sell them but [then] I thought that they would do John more good than the money would me.

I have been downhearted and sick for the last week.

Our equipments is a knapsack, a haversack, a cap box, a cartridge box, a bayonet, scabbard, a canteen, a gun.

I can’t think of anything more to write at present. Be sure and tell Em that she will catch it when I come home. So goodbye from your true friend,

–Robert S. Beckwith

[hr]

The 1st did not head to Harpers Ferry, however, remaining in Washington. The New Jerseyians would eventually cross the Long Bridge on July 12 and march to Alexandria, Va., where they encamped at Roache’s Mills, renaming it Camp Trenton. The brigade consisting of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd New Jersey was commanded by Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyan and designated part of the 4th Division of the Department of Northeast Virginia under Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. On August 4, the 1st New Jersey Brigade was officially formed with the addition of the 4th Infantry, and Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny took command of it.

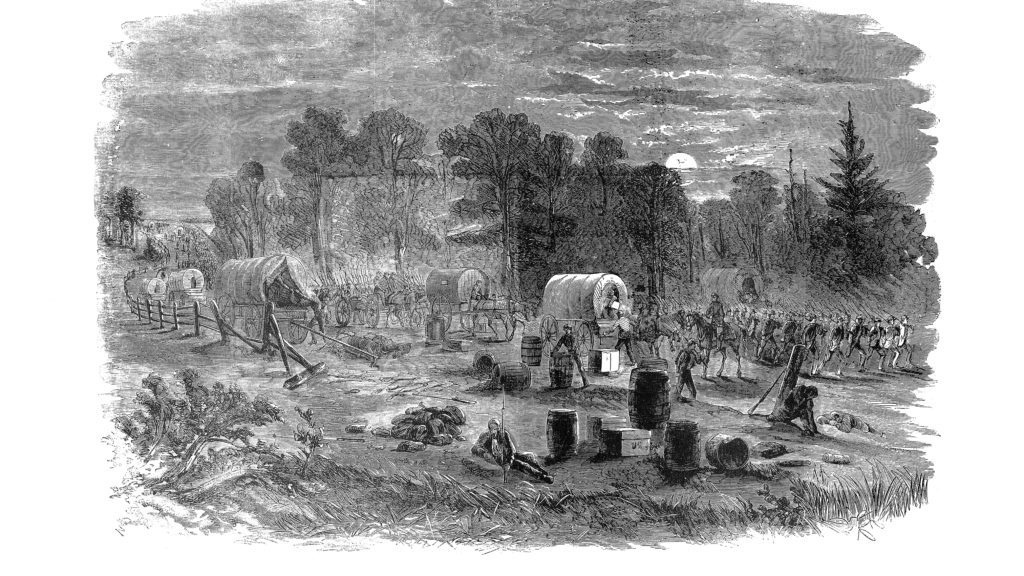

Beckwith wrote the following letter three weeks after the First Battle of Bull Run, which occurred on July 21. The 1st New Jersey did not fight that day, but it was ordered to the front to cover the retreat of the Union forces that had been engaged, and then fell back to the defensive works near Centreville, Va., where they tried to stem a flood, according to regimental Major David Hatfield, of “United States regulars, mounted civilians, soldiers and baggage wagons coming thundering down the hills.” Beckwith, however, did not mention Kearny’s ascension to command or offer details about Bull Run. Instead, after just a few weeks in the military, perhaps prompted by observing the aftermath of the Union defeat, Beckwith grumbled about his life as a soldier and longed to go home. He was also jealous because John Billings’ three-month enlistment with the 1st Pennsylvania had ended and his good friend was back home.

[hr]

1st New Jersey Infantry, August 14, 1861

Dear Friend John and Mary

I just received your letter and am a going to answer it. I am well at present and I hope these few lines will find you the same. We have been almost starving to death for the last month but now they give us a plenty and I hope they will continue to do as long as I am in the service. There is a good deal of talk about going home when our three months is up. They say that they can’t keep us after the 27th of August and if they can’t, you will see one fellow up there that looks like Old Bob.

We have been marched all over the whole South and I am about tired of such fun for too much fun is too much. As the old woman said, “Too much rum is too much, but too much cider is just enough.”

We went to Bull Run to that battle but we did not get any fun so we marched back again. We have had two men wounded. Them [was] W. Mutchler and the other was R[alph R.] Slack. Mutchler was shot through the hand and Slack was shot through the arm and it was taken off above his elbow.

Oh how I wish that story was true. [About the 1st being sent home.] I’d shout for joy, you had better believe, but I don’t expect that it is true for there is now such good news for the New Jersey 1st Regiment as that it is the meanest regiment in the whole brigade. I should like to see you all very much but I don’t ever expect to.

We have moved more than a dozen times from one camp to another and marched more than 800 miles. I hope that if John ever goes as a soldier again, that he will get shot because if I was clear, I am sure I never would go again for they don’t treat their men good enough. They treat them like dogs more than like men. Don’t ever let me see you down here, John. If I do I shall whip you for I say when you get clear, keep clear. Don’t come back again.

We get 15 dollars a month from the government and 4 from the State. That makes 19 dollars a month. 100 would not keep me if I could get away for I have seen the elephant. [unsigned, possibly missing a sheet]

[hr]

By October, the 1st New Jersey had been detailed to build some of the forts that protected Washington. Once again, Beckwith urges his friend John to stay home.

Camp Bushes, October 1861

Dear Friends John and Mary,

I received you letter yesterday and was very glad to hear from you. I thought you had forgot me for I wrote to you so long ago and received no answer, but it has come at last So I know that you have not forgot me nor never will. I know you never will. You are the only one that I have got to think of as a friend or friends. I know you are my friends.

I have not got much new to write at present but I shall have more time after we get through working on the fort. We are building two forts here about three miles from Alexandria, Va. All the New Jersey troops are here together in the woods. We have to work on trenches 6 hours a day for 40 cents extra. That helps some.

Oh, as you said about coming back again to the war, I can tell you [that] you had better stay at home at present for I think that his war will not last very long so you had better stay at home. There is Rebels coming in every day and giving themselves up to us as prisoners of war. I shall be at home some time. We got paid off today the sum of $23.65. I am going to send $15 to [father] T.S.B. of North Windham, Conn. I shall send some next time we get paid.

I see you rewarded for your kindness towards me when I was there with you. I owe a great deal to you for that. You must excuse me for the shortness of this letter. I must close now so goodbye at present from yours &c.

–Robert S. Beckwith

N.B. We are in the Light Battalion now and have got Springfield rifles now. The Battalion is made up from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd Regiment; two companies out of each regiment. We are commanded by Lieut. Col. [I. M.] Tucker. Direct your letter to R.S B., Care of Capt. Mutchler, Co. D, Light Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, Washington[.]

Give my love to all the folks. My respects to Lo Winters of South Easton, Pa. I don’t know when I shall write again so you must not expect me to write very soon for I don’t have much time. So goodbye John & Mary &c.

[hr]

Beckwith and the 1st New Jersey Brigade spent the winter of 1861–62 camped near Washington, and were shipped out to join Virginia regiments after they were assigned to take part in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Spring 1862 Peninsula Campaign. The brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. George W. Taylor, left Washington on April 17 and joined Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s 1st Division in what became the Army of the Potomac’s 6th Corps (Provisional) on May 18. Beckwith’s letter mentions the Battle of West Point, better known as the Battle of Eltham’s Landing, which took place on May 7, 1862, in New Kent County. In this affair, General Franklin’s division disembarked from boats at Eltham’s Landing, where the Pamunkey and the Mattaponi rivers meet to form the York River. They were attacked by enemy troops—far less than the number claimed by Beckwith in the following letter—who were protecting Confederate wagon trains retreating toward Richmond and fighting at Williamsburg on May 5. The 1st New Jersey was only lightly engaged, serving as reserves in this engagement. This letter was written during the Seven Days’ Campaign, and Beckwith mentions the fighting of the previous day in what is commonly called the Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks).

Battlefield Fair Oaks, June 26, 1862

Friend Mary & John,

As I haven’t wrote to you for a long time, I will tell you the reason. I can’t get any stamps & I don’t like to send a letter without a stamp on it but as we are situated, I can’t get them at any price. But you must not wait for me to write. You must write.

I have witnessed some hard fighting. Since I wrote you before, I have been in one fight—the Battle of West Point. Our Division was against 80,000 & held them until we got reinforcements. Then they retreated. I have been sick for some time but am better now.

Yesterday we had a hard fight on the old field. We were in reserve. Them engaged were the 7th Maine, 19th Massachusetts, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th New Jersey, & the Irish Brigade. We drove them 1¼ miles & now we are in sight of Richmond. I can’t write much this time so you must excuse me for so short a letter. But you must write & don’t wait for me for I can’t write as though I was at home.

So excuse me & write soon to your old friend,

–R.S. Beckwith, Private in U.S. Army

R. S. Beckwith

Co. D, 1st Regiment, N. J. Volunteers

Gen. Slocum’s Division

Washington D.C.

[hr]

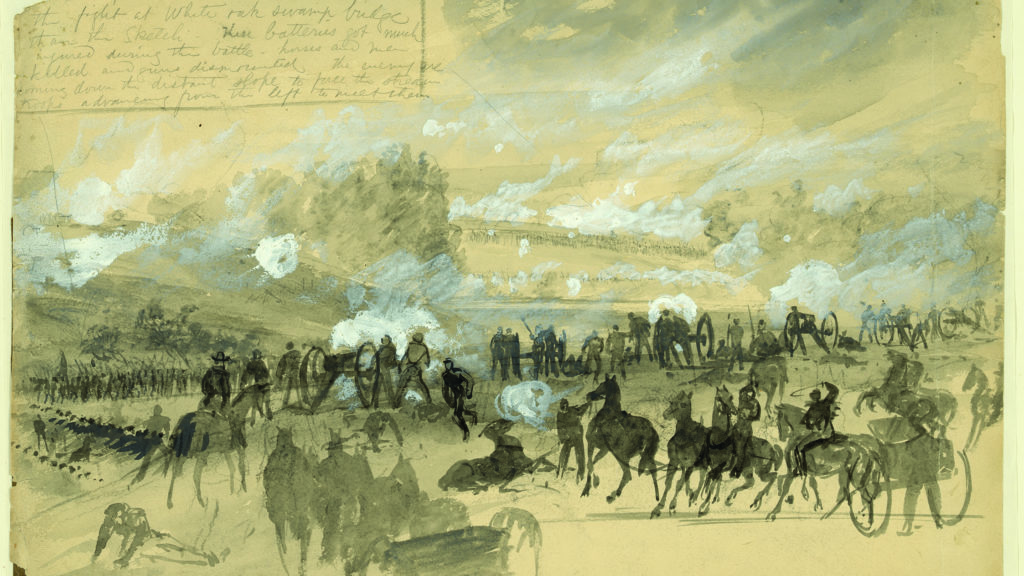

Beckwith was a full-fledged veteran when he penned this letter from the camp of the 1st New Jersey near Alexandria, Va., after returning from the Seven Days’ Campaign, the series of battles during which the Army of Northern Virginia drove McClellan’s force away from Richmond. Beckwith mentions being engaged in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill on June 27, and the Battle of White Oak Swamp on June 30 while on the “retreat” to the James River. His regiment was heavily engaged at Gaines’ Mill, enduring a “leaden hail of an often unseen foe,” according to Brig. Gen. Taylor, and suffered 152 casualties. When Beckwith wrote this letter, he had little more than a month to live.

Headquarters, 1st Brigade, New Jersey Vols., July 25, 1862

Dear friends Mary & John,

I am now out on picket about 5 miles from camp. I am on the outpost. There is 3 of us on the post but the Rebels are not very near so we are not much alarmed about them. I have not got much to write today for I am out on picket but I will tell you about the Battle I was in a few days after I wrote you. It was the Battle of Gaines Mills on the 27th of June. We lost a great many of our brave men in that fight. You have heard all about it, I suppose. The papers tell all about the fight so I can’t find much to write about so you must excuse me for so short a letter but I can tell you the balls flew thick that day’s fight.

You must write as often as you can for you can do so better than I can for we have to go out on picket one day & then go in & then we have to go out on trenches twice a day until we got out on picket again. We go on picket every 3 days & I can tell you we have it pretty hard since we made that retreat. The day after the battle, we started on a retreat & was 3 days coming for we had a fight every [day]. I was in the Battle of White Oak Swamp but did not lose any men.

Oh, tell Susanna that I was surprised the day I was sitting in my tent & who should come & look in but [my brother] Chester. He has been [in] one fight with me but I did not know it at the time. He is in the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery. They lay about one mile from me. We are to go there 2 or 3 times a week. I expect him over tomorrow—Sunday. He was paid off the other day & sent $40 dollars home to Minerva. Chester said he had written to you the other day.

My love to all—also Uncle Peters. He is with us yet.

Yours &c., –Robert S. Beckwith, U.S. Army

[hr]

Following the Peninsula Campaign, General Robert E. Lee moved his army west and north to take pressure off Richmond. Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s wing led the way, and by August 27, Jackson’s men had captured the Union supply depot at Manassas Junction. Taylor’s New Jersey brigade was nearby, and was ordered to push out the Rebel intruders. The sharp fight that ensued was the opening salvo of the Second Battle of Bull Run. The 1st New Jersey was heavily engaged, and suffered the most casualties in the brigade, one killed, 46 wounded, and 55 captured, for a total of 132 casualties. Private Beckwith was among those statistics. He was wounded August 27, according to his service record in the National Archives, on the “Plains of Manassas,” and “Died in hospital at Manassas” the same day. The letter below was written by his older brother Thomas, as the administrator of Robert’s estate, after Thomas had become aware that a trunk of Robert’s possessions was still with John and Mary Billings in South Easton.

North Windham, Connecticut, November 5, 1862

Mrs. Mary C. Billings,

I see by Robert S. Beckwith’s papers that you have in your possession a trunk of clothing [and] also a watch which I wish you to send by Express to me—Thomas S. Beckwith, Administer on the Estate of R.S. Beckwith. Please send as soon as you receive this and save my coming after it as you are held responsible for them until I receive them, which must be as soon as you can make it convenient.

Yours respectfully,

–Thomas S. Beckwith, No. Windham, Ct.

William Griffing was profiled in the August 2019 issue of this magazine. He resides in Batavia, Ill., and maintains the Facebook page and website “Spared and Shared,” where he posts transcriptions of Civil War–era soldier and civilian letters.

_____

Brothers in Arms

Robert Beckwith’s older brother, Chester, served in the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, a unit trained to use the largest cannons in the Union arsenal. Chester mustered in for three years on March 15, 1862, at age 35, relatively old for a Civil War soldier. The red-haired, blue-eyed prewar carpenter’s ability to work with his hands was appreciated by his batterymates, and he was appointed an artificer, a soldier skilled in repairing equipment, for his company on January 10, 1864. During the Siege of Petersburg, Va., the heavies were distributed throughout the Union army’s lines, and Chester’s Company C was stationed in Fort Rice, north of Fort Sedgwick in the area held by the 9th Corps.

During the Battle of the Crater on July 30, Company C fired 360 rounds from its 10-inch siege mortars in an effort to suppress Confederate gunfire on the right flank of the attacking Union columns. During the bombardment, Chester suffered a concussive injury that would plague him for the rest of his life. He remembered that he “was stationed at the mouth of [the] Powder Magazine…and employed in sawing [cutting] fuse. While so engaged the concussion produced by the firing of the heavy siege guns and mortars injured both of my ears so that blood came from them…during many months afterward I was troubled with a discharge of matter from both ears….”

On May 29, 1879, Providence, R.I., resident Elisha Jordan, who had served as a sergeant in Company C of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, wrote a letter to the U.S. Pension Office affirming Beckwith’s injuries. During the attack, Brig. Gen. Henry L. Abbot, commander of the siege artillery train, described how his mortarmen were opening up 12-pounder canister rounds and putting the individual iron balls into hollow 10-inch shells to create more shrapnel. Abbot claimed that it was “probably the first [instance] in which spherical case from heavy mortars was used.” Jordan’s letter confirms that expedient practice. Soldiers sometimes used the term “grape shots” in place of canister.

“…I was on duty…near Fort Rice in front of Petersburg Va on July 30th 1864. I know that Chester H. Beckwith was an artificer…and was on duty in the bombproof sawing fuses during the explosion of Burnside’s mine and attack on enemy line….I was ordered to go in the bombproof and direct said Beckwith to put 27 grape shots into a shell which I did and found Beckwith with his ears bleeding badly….I know that ever after this day while in the service Beckwith was excused from roll call because his hearing was bad….”

Beckwith suffered deafness from his injury until he died on November 13, 1909. His second wife, Mary, who he married in 1903, recalled that occasionally “the blood would run out of his ears and head,” and that “he was [in] dretfull suffer as long as he lived….” Herself sick and destitute, Mary applied for a widow’s pension in 1912, but it was denied because the government determined that Chester’s wartime injuries did not cause his death. The information presented here can be found in Chester Beckwith’s pension file at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. –Dana B. Shoaf