A soldier’s diary preserves the only known text of an Emory Upton speech

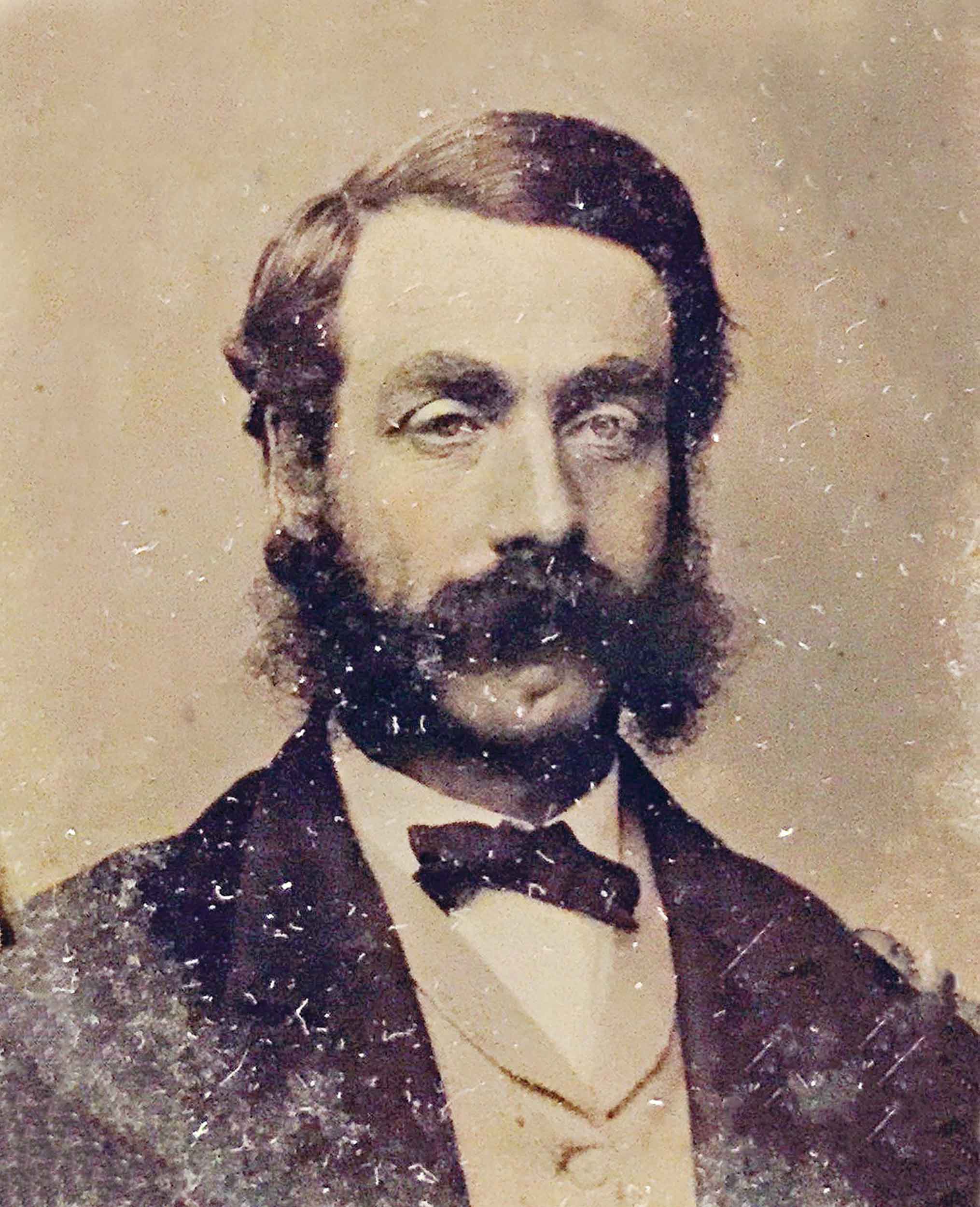

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]n entry in the 121st New York’s regimental books describes Private Albert N. Jennings as a “good soldier but lacks constitution,” which doesn’t quite seem to suit a man who served the Union cause throughout the war and survived wounding at the Battle of the Wilderness. Born October 15, 1837, the only son of Samuel and Catherine Jennings in the tiny hamlet of Salisbury, N.Y., he left at age 24 to join the Army, perhaps inspired by a desire to impress 18-year-old Martha “Mattie” Woolever, a local girl to whom he had taken a shine.

The regiment mustered in on August 23, 1862, for three-years service with 946 men and 36 officers. Recruited mainly from Otsego and Herkimer Counties in Upstate New York by Richard Franchot, who became the 121st’s first colonel, the regiment left for Washington City after only one week of drill.

Arriving at Fort Lincoln in Washington’s northwest defenses on September 3, the men finally received English-made Enfield rifle muskets and began learning the manual of arms. Only four days later, the regiment left Fort Lincoln in the middle of the night without most of its equipment, expecting to return after a brief skirmish. The regiment never made it back to the fort or recovered its original gear, a disaster the men blamed on their green commander, Colonel Franchot.

Joining Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s 6th Corps—assigned to Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s 1st Division and Colonel Joseph Bartlett’s 3rd Brigade—the 121st chased General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army into Maryland, witnessing but not participating in the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam. The 121st men nevertheless suffered for weeks with nothing but their uniforms to shield them from the night’s chills and drenching rains, a condition that fostered growing resentment of their leader.

Perhaps knowing he was in over his head, Colonel Franchot resigned his commission after only one month. Determined to leave his regiment in the capable hands of a professional officer, Franchot used his friendship with General Slocum to ensure his hand-picked replacement was Captain Emory Upton, who would prove to be one of the most remarkable young commanders of the war.

Upton took command of the 121st on October 25, 1862, and immediately began to transform the volunteers into a crack fighting unit. He established Regular Army routines and established certification tests for officers. Upton forbade spitting, demanded attention during formations, and instituted new hygiene and medical practices to repair the physical toll from the Maryland Campaign. Other regiments in Bartlett’s brigade began referring to the 121st New York as “Upton’s Regulars.”

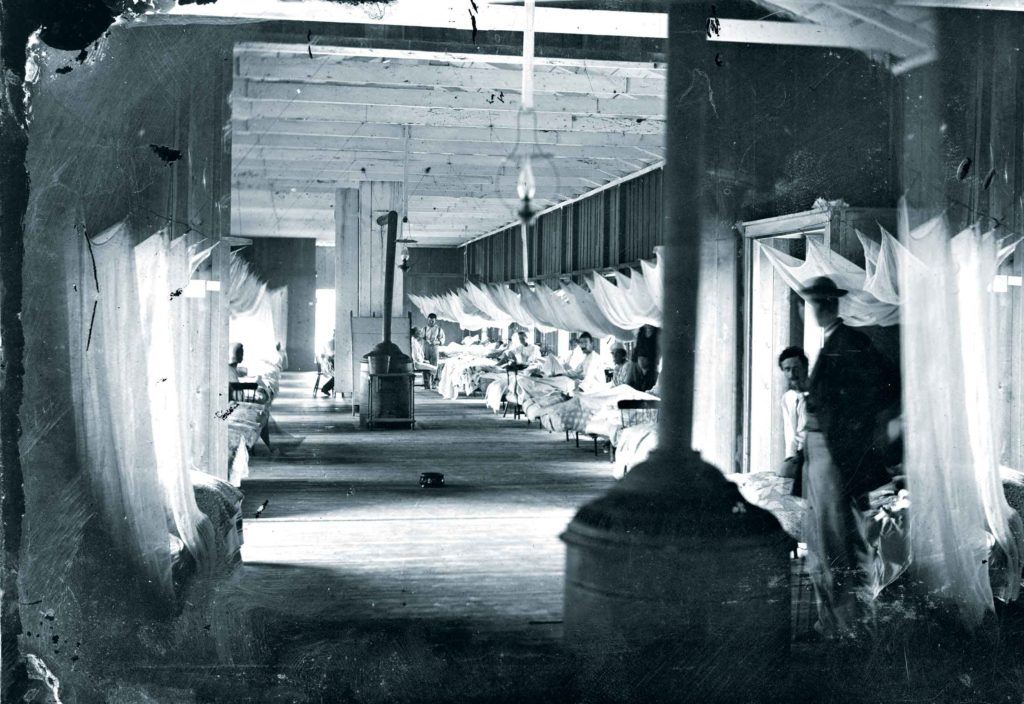

Jennings, however, missed some of that transformation when he found himself at Harewood General Hospital outside Washington, D.C., rather than in the 121st’s winter camp at White Oak Church near Fredericksburg, Va. By early 1863, Albert reported to Alexandria’s Camp Distribution, where men were processed returning to their various units in the field. Once there, Albert for the first time served as Company H’s clerk, and said he “wrote some for the captain.”

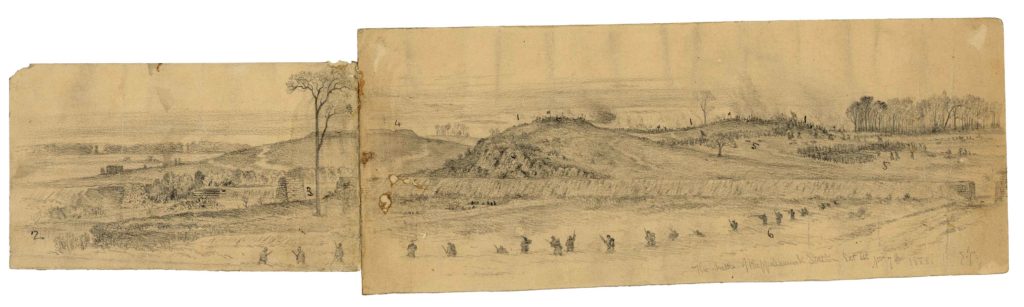

In early May, Jennings’ regiment participated in Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Chancellorsville Campaign. The 121st, part of Brig. Gen. William Brooks’ 1st Division, waited with the 6th Corps in the Union rear, guarding the Rappahannock River crossings while the rest of the Army of the Potomac fought at Chancellorsville.

On the evening of May 2, Hooker ordered Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, then commanding the 6th Corps, to reinforce his battered army at Chancellorsville. After successfully driving Confederate defenders from Marye’s Heights, the 121st ran headlong into a Southern defensive line near Salem Church. In 20 minutes, the regiment lost 137 men killed or wounded, and retreated across the Rappahannock. Jennings’ diary entries track the advance of his regiment.

1863

APRIL 28: Across the Rappahannock. We crossed the river this morning and drove the Rebs back from the river and I have been out on picket today. The Rebs are in plain sight. We crossed [in] pontoon boats. The Rebs fired on the first boats that come over and we had three or four killed.

May 1: Today we laid on [our arms] in line of battle and there is a little skirmishing along the front….

May 2 [Battle of Chancellorsville]: Today we had some shells come over from the Reb batteries and we dug rifle pits to screen us. There is a good deal of skirmishing on our front.

May 3 [Battle of Salem Church]: Today we advanced on the Rebs. We marched through Fredericksburg and out the road toward Gordonsville. We took the heights above Fredericksburg….We drove the Rebs a few rods and had to fall back. We rallied and drove them back again and held our position. We lost almost half our number.

May 4: Today we have been under fire but have not been engaged. To night we retreated across the river. The Rebs came near flanking us. We were the rear guard and covered our army’s retreat.

Following the Chancellorsville debacle, the 121st New York pursued the Army of Northern Virginia as it headed north. Arriving at Gettysburg, Pa., in the midafternoon on July 2 after a brutal 30-mile nighttime march from Manchester, Md., Bartlett’s brigade deployed on the northern shoulder of Little Round Top to support the 5th Corps (which Jennings mistakenly calls the 12th Corps). On July 3, the 121st remained in reserve and witnessed Pickett’s Charge. Jennings recorded the experience in his diaries, referring often to Martha as “M.”

June 26: Today we got up at 3 AM. Broke camp and marched till 4 o’clock P.M. [W]ere rear guard tonight; went and got some cherries & milked some cows….We came through Gainesville, Loudon Co. Va.

June 27: Today we marched to near Poolesville Md. We crossed the river at Edwards Ferry. We passed though a fine section of country. It is now rather damp. We are now in Montgomery Co. Md.

June 28: Today we marched through Poolesville. It is cool and good marching….We come round Sugar Loaf [Mountain] and we marched about 26 miles through a fine section of country….

June 29: Today we broke camp and marched 26 miles. We come through the village of Monroeville, New Market, & Ridgeville and Simons Creek. It was rather damp, so we had a hard march.

June 30: Today we marched about fifteen miles through the village of Westminster, which is quite a nice little village in Carrol Co. Md. I stood the march much better today than I did yesterday.

July 1: [Battle of Gettysburg]: Today we have lain in camp all day and have only been after water and sent three letters, one to…M….We marched again tonight. It is quite warm and was about used up.

July 2: Today we marched till four o’clock P.M. After marching all night, I was obliged to fall out but caught up soon after they stopped. We marched through Littlestown [Pa]. We came into Penn. in the forenoon. I had just caught up with the Regt. and had to go and support the 12th Corps that was engaged with the Rebs but did not get into the fight & lay on our arms all night but was not disturbed.

July 3: Today we have laid under arms all day and fired at the Rebs, there has been heavy fighting since before noon but none of us are injured. We have thrown up breastworks but have not used it….

July 4: Today we have been out in front but did not get into a fight and we lay where we did yesterday. There has only been a little picket firing. I have written to my Father & M. We had a heavy rainstorm this afternoon.

July 5: Today we followed up the Rebs, who are retreating. They left their wounded all in our possession. We overtook them about sundown and shelled them some and took two wagons. It is very wet and muddy marching….

After chasing Lee’s army back into Virginia, the 121st settled into camp at New Baltimore, and Jennings found himself serving as Colonel Upton’s orderly. By early October, the 121st was on the move again in the Bristoe Station Campaign. On November 7, the regiment played a central role in the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station, Colonel Upton’s first opportunity to command a brigade in battle and in which the 121st helped capture the only Confederate crossing of the Rappahannock. This often-overlooked Union victory became a point of pride for the 121st.

August 10: Today I am the colonel’s orderly and it is very hot. I received two letters tonight, one from L.J. & one from A. E. Cough, Kingsboro….

October 15: We marched about ¼ of a mile and built some rifle pits and we are now waiting for the enemy to make their appearance….Today I am 26 Yrs. Old.

November 7: [Battle of Rappahannock Station]: Today we have broke camp and marched to the Rappahannock Station and where we charged a post and took 308 prisoners and 4 stands of colors….

The 121st spent the winter of 1863-64 near Brandy Station, Va., and in the spring learned that Colonel Upton had received command of the 2nd Brigade. On May 4, the regiment moved south to open Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant’s Overland Campaign, and fought at the Battle of the Wilderness. Early in the battle, Albert was shot in the right arm—becoming one of the regiment’s 73 Wilderness casualties.

1864

May 4: We broke camp at daylight and crossed the Rapidan at Jacobs ford at little after noon….

May 5: We broke camp this morning at five o’clock A.M. and our skirmishers found the Johnnies and there was some heavy fighting all along the line.

May 6: [Battle of the Wilderness]: To day we put up some defenses and in the fore part of the evening we had a fight. They turned our right flank. I was wounded in the fore front part of the action, between the elbow and shoulder of the right arm. I came out of the fight and had the ball taken out and done at the 2nd Div’s hospital.

Albert’s wounding spared him some of the most costly fighting the 121st New York would endure. On May 10, the 121st formed part of Upton’s innovative, concentrated attack on the Mule Shoe at Spotsylvania, which breached the enemy fortifications. A lack of reinforcements, however, undid the Union gains. Still, the assault earned Upton a promotion to brigadier general. On July 10, the regiment boarded steamers heading north toward Washington, D.C., to resist Jubal Early’s advance on the Union capital following his victory at the Battle of Monocacy. The New Yorkers then joined Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley and participated in the fighting at Opequon, the Third Battle of Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek. The regiment eventually bid farewell to General Upton at Harpers Ferry that November when he was assigned a division in Maj. Gen. James Wilson’s Western cavalry force. In early December, the 121st rejoined Grant’s army at Petersburg. Albert Jennings returned to the 121st New York at Petersburg after a month-long furlough and five months at Washington’s Emory Convalescent Hospital. Early February brought Jennings and the 121st a return to fighting at Hatcher’s Run, as Grant moved left to overextend and thin Lee’s lines guarding Petersburg. By the end of March, the regiment took part in repulsing Lee’s last assault, at Fort Stedman, before advancing at long last into Petersburg.

1865

February 6: [Battle of Hatcher’s Run]: We advanced about three miles and got engaged with the Johnnies. Just before sundown W Greggs was very severely wounded…..We were relieved by a portion of the 5 Corps….Received a letter from Mat.

March 22: Today we were reviewed by Genl. Meade, Wright, Wheaton, and Admiral Porter. It is very hot and pleasant….

March 25: [Battle of Fort Stedman]: The Johnnies attacked on our right and we had to go down, but it all was over with when we got there. We come back and went to the left and made a charge on the enemy’s lines and drove them in and took some 400 prisoners. I am feeling well. We only had a few men killed and wounded in our regt. I blistered my feet considerable in the march….

April 2: This morning at 1 o’clock we moved off to the left. We made a charge on the enemy works and then took them and captured thirteen pieces of artillery and 500 prisoners. [We] had one man killed (J. Hendrix) and a few wounded….Were relieved by the 24th Corps and went down to the right. Near the 9th Corps, [the] 24th Corps and our Brigade were sent down to the left to support the 9th Corps. We were under a pretty sharp fire….We remained in the enemy works until four o’clock and then advanced on Petersburg, where we arrived and entered the city at day light. Marched through some of the principal streets and were then sent out to patrol the city for prisoners. We stayed until near noon and then returned to our old camp for our knapsacks and remained there one hour and again marched off to the left. We marched until seven o’clock and went into camp for the night—having marched about 10 miles from Petersburg. I am feeling well but rather sore about the feet.

Lee and his army abandoned Richmond, and the 121st New York joined in pursuing the Confederates. During the Battle of Sailor’s Creek, the 121st accepted the surrender of General Lee’s oldest son, Custis Lee, and General Richard Ewell and his corps. By April 9, the 121st arrived at Appomattox Court House, where the New Yorkers witnessed the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia.

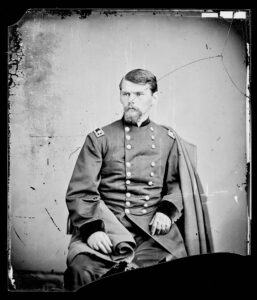

Emory Upton: Military Visionary

The real gem of Albert Jennings’ diary is his transcript of Emory Upton’s farewell address to the 121st New York, given at Harpers Ferry in late November 1864. Jennings was in the hospital at the time and did not hear the address in person, but might have seen the text while working as the regiment’s clerk, which he then copied into his journal. Here is his version of Upton’s words, published for the first time.

Genl. Upton’s Farewell Address to the 121st Regt NY Vols

In talking of the gallant regt. which I have had the honor so long to command, I cannot refrain from expressing the affection and regard I feel for those brave officers & men with whom I have been so long & pleasantly associated. I thank you everyone for the kindness and courtesy which has ever shown me, and the alacrity with which my orders have been obeyed. Your record is one of honor, and I shall ever with pride claim association with the 121st Regt. The distinguished past—borne by you in the battles of Salem Heights, Rappahannock Station, Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, Cedar Creek and many others—has made for you a history second to no regt. in the Army. But above all that is the present satisfaction of having voluntarily periled your lives in the defense of the noblest governments on earth and by your valor helped to place its flag first among nations. Many of you cannot reap the immediate reward of your service but the time is fast approaching when to have participated in your glorious battles will entitle you to the highest respect among men. Let your future rival them in valor and devotion. I leave you in brave hands and part from you with sincere regret.

Brigadier Gen E. Upton

Upton was born on August 27, 1839, in Batavia, N.Y., to a family of Methodist reformers. He was an ardent abolitionist long before entering Oberlin College and, in 1856, West Point. Graduating eighth in the Class of 1861, he rose quickly through the ranks, first with the 4th and then the 5th U.S. Artillery, before landing a post on Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler’s staff. In this capacity, Upton was wounded during the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford—the day before the First Battle of Bull Run. Returning to the 5th U.S. Battery, Upton led it through the Peninsula Campaign and rose yet again to command the 6th Corps’ 1st Division artillery brigade during the Maryland Campaign, a position that introduced Upton to the 121st’s Colonel Franchot.

After the war, Upton returned to West Point as commandant from 1870-1875, and advocated for the Army reforms his personal study and Civil War experience suggested the United States needed. He favored abandoning line formations in favor of small unit assaults based in part on the operations of Civil War skirmishers—outlined in his 1867 manual Infantry Tactics.

After conducting a detailed survey of military forces around the world in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, he wrote The Armies of Europe and Asia. This work argued for a larger, permanent standing U.S. Army and introduced the first moves toward professionalizing the Army—advocating regular performance reviews and examination-based promotions—as well as proposing creating a Prussian-style General Staff and establishing service-specific military schools. Upton expanded on these ideas in his draft work The Military Policy of the United States from 1775, which was published after his death. Tragically, Upton had for years suffered from tremendous headaches—probably the result of a tumor—which may have caused the 41-year-old to end his life on March 15, 1881.

April 4: To day we broke camp at half past three o’clock A.M. and moved out at five o’clock. We marched about 8 miles and went into camp for the night at a little after dark….

April 6 [Battle of Sailor’s Creek]: …We broke camp at daylight and moved off by the left flank. We got into a fight before night. G. Lampshear was killed and J. Morris. We had several killed in the Regt. and 14 wounded. We captured Gen Ewell and Gen Lee’s son.

April 9: Today we broke camp at day light and…overtook the second Corps. It is pleasant but there is some cannonading in front. 2 pm the Rebel Army was surrendered by Genl Lee. There was considerable noise made in honor of it among the soldiers. There was two hundred guns fired in honor….

The war was over for Albert Jennings and his comrades in the 121st New York. After participating in the Grand Review of the Army of the Potomac in Washington, D.C., on May 23, the regiment mustered out on June 25, 1865.

Jennings returned home to New York, completed high school, and married Martha Woolever on April 19, 1866. Jennings and his wife moved to nearby Dodgeville, where Albert worked as a carpenter in the Albert Dodge Piano and Felt Factory, until moving to Lloyd sometime before 1900. Jennings suffered a heart attack while attending a G.A.R. encampment in Saratoga Springs, and passed away on September 13, 1907.

David A. Welker is the author of Tempest at Ox Hill: The Battle of Chantilly, among other publications on the war. He served as a U.S. government historian and military analyst for 35 years and lives in Centreville, Va., with his wife.

Jeffrey R. Fortais is an avid military historian and collector who frequently gives presentations on the Civil War and World War II. A technology teacher for 23 years, he lives in Camillus, N.Y., with his wife and two daughters.