The galley—a large seagoing vessel propelled primarily by rows of oarsmen but supplemented by sails—dates from the third millennium BC. The war galley was fitted with a projecting beak at its prow, used for ramming. Rounding out its armament were archers, catapults and incendiary devices. If one couldn’t ram and sink or set afire an enemy ship, a last resort was boarding and capture.

By the 16th century gunpowder had been added to the galley’s arsenal, though its design initially permitted only bow-mounted cannons. A later hybrid, the galleass, provided dedicated gun decks on which to carry more cannons, though it too relied primarily on its ram.

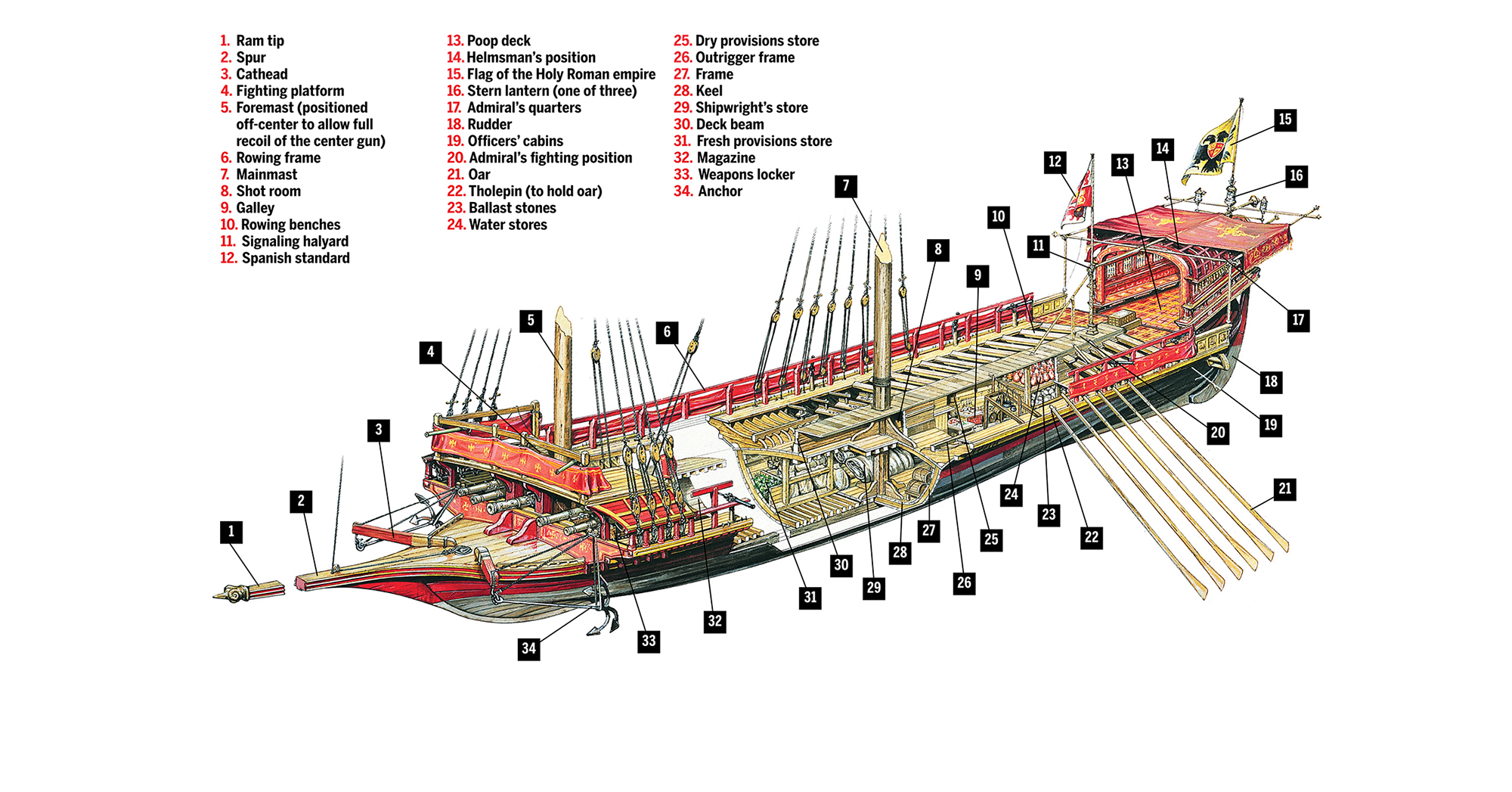

The great galley fleets that gained fame at the 480 bc Battle of Salamis and amid the 264–41 BC First Punic War reached their zenith during the pivotal collision of the Holy League and Ottoman empire off Lepanto, Greece, in 1571 (see related feature). The example shown here is a Spanish galley of the Holy League fleet. By then, however, Henry VIII had ordered the construction of sail-powered warships fitted with rows of cannons as the backbone of the English fleet. Galleys, whose shallow draft and crew logistics limited their oceangoing capabilities, occasionally turned up in combat as late as the 18th century, but almost always as coastal or riverine warships.

The use of naval rams saw an unexpected revival amid the American Civil War when the Confederate navy introduced steam-powered casemate ironclads fitted with bow rams and rows of cannons. The modest success of these ironclads prompted the Western powers to roll out a generation of warships sporting such rams—that is, until the 1894–95 First Sino-Japanese War made it clear even steam-powered armored rams were no match for high-explosive armor-piercing shells. With that, the ram concept went down for the last time. MH

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Military History. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.