GEORGE AND ELIZABETH SPANGLER had worked hard to cultivate their farm south of Gettysburg. When they purchased the property in 1848, seven years after they married, it consisted of only 80 acres. By 1863, however, the farm had expanded to 166 acres. Their prosperity—the real estate was valued at $5,000 in 1860—kept the elder Spanglers and their four children (two girls and two boys, ranging in age from 14 to 21) busy with innumerable chores.

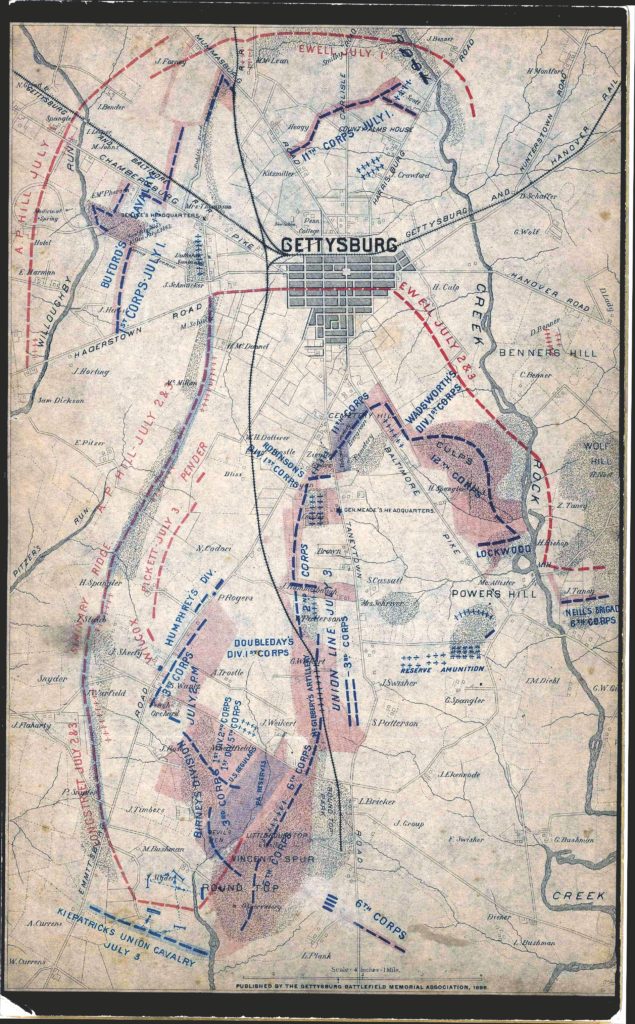

Part of that prosperity was also due to the farm’s location. Good roads such as the Baltimore Pike, Blacksmith Shop Road, and Granite Schoolhouse Lane gave the Spanglers easy access to other areas of their community and the nearby agricultural hub of Gettysburg. But in July 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg, that same location made the farm a target.

Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill to the north, Cemetery Ridge to the due west, and Little Round Top to the southwest went from pleasant local landmarks to blood-soaked battlefields in the blink of an eye. And then horrible war came calling at the Spanglers’ front door on July 1 when surgeons from the Army of the Potomac rode down the lane and told the shocked family their farm was now the 11th Corps hospital.

The Spanglers’ world shrank to one upstairs room where they lived from that day until August 6 as moaning, wounded men replaced the lowing cattle in their barn, and troops and artillery pieces crushed their wheat and battered their fruit trees. By July 3, the mass of confusion and agony on the farm was overwhelming surgeons desperately sorting through the wounded in an attempt to find those who could be saved with immediate attention. Since the first day’s fight, the 11th Corps wounded had been joined by shot-up men who had drifted to the property or had been brought from other areas of the battlefield.

And then Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Armistead arrived in an ambulance. Despite the chaos, heads turned. Hospital workers and a few of the wounded who could walk crowded quickly in a circle around the ambulance. Although they likely had no idea what Armistead had accomplished during the charge that day—the way he had placed his hat on his sword and rallied his brigade of Virginians over a stone wall at the center of the Union line before being struck down—they were drawn to the general’s presence.

Army of the Potomac surgeon Henry Van Aernam of the 11th Corps’ 154th New York Infantry estimated Armistead’s arrival at the Spangler Farm at about dusk—roughly 8 p.m., more than four hours after the general had been mortally wounded near Gettysburg’s famous Copse of Trees. Lying on a stretcher, he was placed on the ground near the Spanglers’ large bank barn. According to Privates Emory Sweetland and Edson Ames, hospital workers from the 154th New York, Armistead was, respectively, “pretty bloody” and “covered with blood.” Sweetland added that Armistead announced, “You have a man here that is not afraid to die.”

Dr. Van Aernam broke up the crowd of gawkers and had General Armistead carried away for treatment. The general would die the morning of July 5, however, in the Spanglers’ summer kitchen.

Ambulances spent July 4-5 picking up Union wounded who had been trapped behind Confederate lines or in Confederate hospitals, and the crowd at the 11th Corps hospital would grow to about 1,900 wounded or dying soldiers, including between 50 and 100 Confederates. The Granite Schoolhouse, on the Spanglers’ property about a quarter-mile from the barn, would become the home of a 1st Division, 2nd Corps hospital.

Located behind the center of the Army of the Potomac’s line, the 166-acre Spangler Farm had plenty of land and buildings to accommodate the demand that had suddenly been placed on it. There was a kitchen, plenty of wood, and adequate streams and wells for water. The farm was located between the Taneytown Road and the Baltimore Pike, and combined with the aforementioned Blacksmith Shop Road and Granite Schoolhouse Lane, that meant wounded could be transported to the hospital quickly.

Also crucial was the Spanglers’ bank barn, a common feature of the farmland around Gettysburg and elsewhere in Pennsylvania—what one wartime newspaper reporter called “great horse palaces” for their size and beauty. Every inch of the bank barn would be needed during the battle and afterward, with one doctor estimating that 500 men were crammed onto both floors of the building at one point.

Medical staffers of the 11th Corps took control of the property during the mid-afternoon of July 1 and restricted George, Elizabeth, and their children to an upstairs bedroom in their house. That first day, 11th Corps wounded began to arrive by 4 p.m. from heavy fighting both north of Gettysburg and in the town.

rom the 1st of July till the afternoon of the fifth, I was not absent from the hospital more than once and then but for an hour or two,” wrote Daniel G. Brinton, the 11th Corps, 2nd Division surgeon-in-chief. “Very hard work it was, too, & little sleep fell to our share. Four operating tables were going night and day. Many of them were hurt in the most shocking manner by shells. My experience at Chancellorsville was nothing compared to this…I never wish to see such another sight. For myself, I think I never was more exhausted.”

A fellow surgeon, excessively fatigued as well, called the commitment “too much for human endurance.”

“At the doorway I saw a huge stack of amputated arms and legs, a stack as high as my head!” said Private William Southerton of the 75th Ohio Infantry. “The most horrible thing I ever saw in my life! I wish I had never seen it! I sickened.”

Lamented Private Justus Silliman, 17th Connecticut: “The barn more resembled a butcher shop than any other institution. One citizen on going near it fainted away and had to be carried off.”

Most amputations and surgeries took place under the Spangler barn’s forebay. Under the 7-foot extension built for added storage, doctors had more light and fresh air away from the smells of infections and crowds inside the barn. It also was safer for flammable anesthesia use at night, when lanterns were burning. The surgeons worked under the forebay with their backs to the barn. A surgeon would finish one amputation or operation in 5–15 minutes and then move immediately to the next one. No washing was done of bloody or germ-infested hands or bloody equipment, because the physicians did not understand how proper sanitation could prevent infection and reduce the spread of disease. Sometimes, a Spangler surgeon with germ-covered hands would put his hands in a soldier and infect that soldier with a disease. The almost shoulder-to-shoulder crowding of the barn also encouraged the spread of such deadly infectious diseases as gangrene and typhoid fever. Many men died at the 11th Corps hospital not of their battle wound but from a disease contracted at the farm.

Major Generals George G. Meade and Winfield Scott Hancock had a battle and war to win so they banned all hospital wagons from Gettysburg except those carrying supplies for surgeries in order to keep the roads clear for fast troop movement. That had a direct, dramatic impact on the 11th Corps hospital during and immediately after the battle, leaving it without food, tents, hospital clothing, bedding, bedpans, blankets, and more. Men were placed outside in the open once the Spangler buildings filled.

Private Henry Blakeman of the 17th Connecticut, a patient at the barn, said: “We saw pretty hard times lying on the ground.…I was wet through and had not half enough to eat. I wore the same shirt that I was wounded in all bloody for nine days and half that time it was full of maggots & I wore the same pants.…”

Corporal William R. Kiefer, a hospital steward from the 153rd Pennsylvania, said of July 4: “Hundreds were lying with but feeble, or in most cases with no shelter, exposed to a cold incessant rain against the sides of the barn, and in an orchard adjoining the sheds. Their moans were heard in every direction, and with a lantern I moved about from one to another during the long hours of the night. I searched in vain for blankets to cover the suffering and dying.”

Unpaid nurses Marilla Hovey of Dansville, N.Y., and Rebecca Lane Pennypacker Price of Phoenixville, Pa., played important roles at the 11th Corps hospital. Hovey and her 17-year-old son, Frank, traveled with her husband, Dr. Bleecker Lansing Hovey of the 136th New York, and she nursed the wounded and wrote home to family members of the dead and dying.

In one letter from the Spangler hospital, Hovey informed a family of their son’s death and told them: “I have had a good deal of care of him and called him my Soldier Boy and tried to take the place of Mother Sister & Friend. I think I never had such a trial parting with one that I had no more acquaintance with.” The Hoveys worked at the 11th Corps hospital the entire five weeks it was open before returning to New York for a three-week break.

With donations from Phoenixville’s Ladies Union Relief Society, Nurse Price rode to Gettysburg on a bench in a railroad cattle car shortly after the battle, then went to work at Spangler. “The sad scenes would fill a volume,” she said. “So many times at night I lay on my stretcher weeping instead of sleeping.” She tried to help 21-year-old 1st Lt. Joseph Heeney of the 157th New York. Price held an umbrella to protect him from the July sun as he was taken to the barn for a leg amputation. His wound proved mortal.

For a month, she helped to nurse 1st Lt. Thomas Wheeler of the 75th Ohio, before he died of wounds in his right side, right leg, left groin, and left arm. His parents were at his side and Nurse Price sang “Rock of Ages” to him as he passed away. Years after the war, she wrote that her Spangler Farm memories still “filled her heart with sadness.”

Assistant Surgeon William S. Moore of the 61st Ohio Infantry also died there—the only Army of the Potomac surgeon or assistant surgeon to be killed at Gettysburg. During the Confederate bombardment preceding Pickett’s Charge, Moore was mortally wounded by a shell fragment that struck his leg. He left behind a young widow, Sarah, and two children, ages 1 and 2. Sarah was so torn by grief that she mourned for the remainder of her life and never remarried.

It’s not surprising that in a battle the size of Gettysburg, many wounded men did not reach their appropriate corps or division hospital. Sergeant Nelson W. Jones of the 3rd Maine, 20 or 21 years of age, was an example of that. The 3rd Corps soldier died at the Spangler Farm after being hit in both legs in the Peach Orchard by a cannonball on July 2. He made and applied tourniquets by himself on the battlefield to prolong his life, but they were not enough to prevent his death at the hospital.

The majority of 11th Corps hospital patients survived, however, including Captain Alfred E. Lee of the 82nd Ohio, who went home from Spangler Farm with a hip wound only to find his obituary printed in his hometown newspaper. He showed up at his funeral as it was taking place. Corporal James Brownlee of the 134th New York survived seven gunshot wounds at the Brickyard on July 1, one breaking four of his ribs. Brownlee had also been shot through the bowels and in the left thigh, right thigh, and lower back.T

Of the estimated 1,900 wounded men treated at the 11th Corps hospital, nearly 140 are known to have died there, and most were buried in the Spangler orchard. They were exhumed in later months and reinterred in the battlefield’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery, where President Abraham Lincoln famously delivered his Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863. The four known Confederates buried at the Spangler Farm, in addition to Armistead, are believed to have been exhumed in 1872 and reburied somewhere in the South.

In addition to the two hospitals on their property, on July 2, George and Elizabeth Spangler hosted the Artillery Reserve of the Army of the Potomac, which consisted of the 106-cannon, 2,300-man Artillery Reserve and a 100-wagon ammunition train. The 11,000-man 5th Corps arrived on the Spangler Farm and nearby farmsteads at about noon and rested there before rushing through the heart of the Spangler Farm toward the desperate fighting on and around Little Round Top. The 6th Corps rested briefly on and near the farm after the 5th Corps departed and before elements of the 12th Corps passed through from nearby Culp’s Hill. Dozens of 11th Corps ambulances were also on the farm. The 4th New Jersey was there guarding the army’s ammunition train, and there were several other smaller artillery and infantry bivouacs on the property. Powers Hill, a portion of which was on the Spangler Farm, overlooked the Baltimore Pike. It hosted a signal station, 12th Corps and Artillery Reserve cannons, the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, 6th Corps, as well as Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s 12th Corps headquarters July 1-5 and General Meade’s headquarters the night of July 3 and morning of July 4.

Other farms were the sites of more combat than the Spangler Farm, and some were literally destroyed. But no single farm played a more important role during the battle than the Spangler Farm. The family got its farm back on August 7, 1863, after all of the wounded were shipped off to Camp Letterman near Gettysburg and general hospitals in bigger cities, such as York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. They filed three damage claims totaling about $5,000 to the state and federal governments in the 1870s, but received only $90 for six tons of hay.

The U.S. quartermaster’s agent said: “The Government of the United States is no more responsible for bringing on the battle fought there than it would have been had a tornado passed over that country causing as wide spread destruction as did that terrible engagement.…That battle and hospital damage was his misfortune.” All six Spanglers survived their Gettysburg ordeal. They undoubtedly received help from the Sanitary and Christian commissions and other Adams County farmers as they put their farm and lives back together. George said he rebuilt faster than expected, and by 1870 the Spanglers had added on to their house.

The Gettysburg Foundation purchased the 80 acres left of the property in 2008 and restored the barn, summer kitchen, and smokehouse. The Foundation opens the farm for visitors on June, July, and August weekends. The Spangler house has been turned into a modern education center, and the property and buildings have an 1863 “feel.” Visitors can see the farm where Armistead spent his final three days, where two hospitals saved so many lives, and where the Army of the Potomac set up the victory that helped preserve a nation.

_____

Schoolhouse Hospital

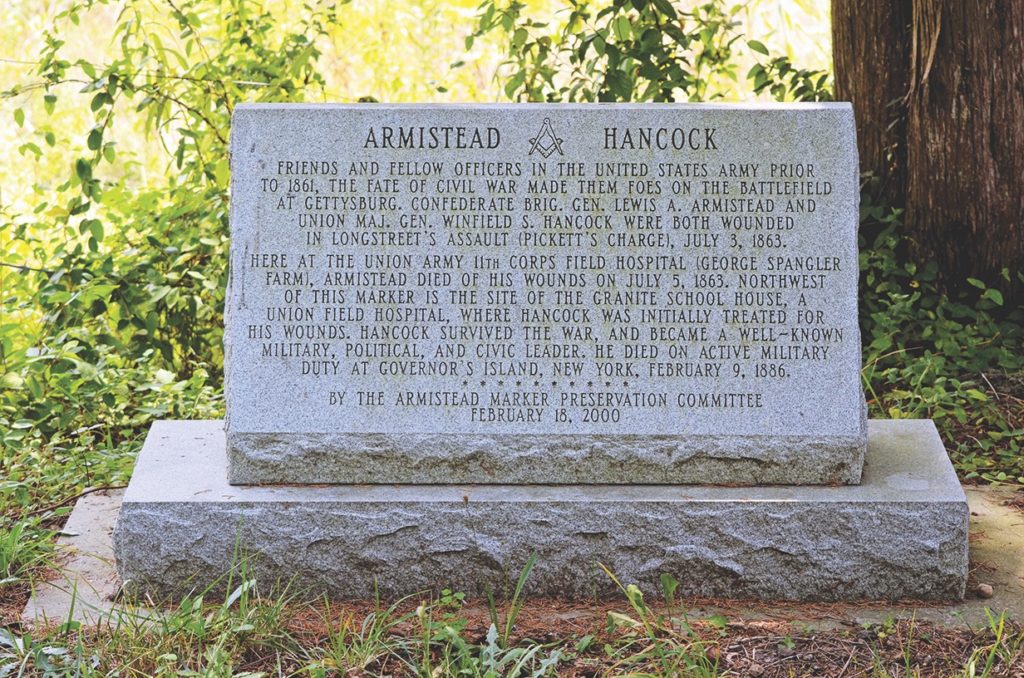

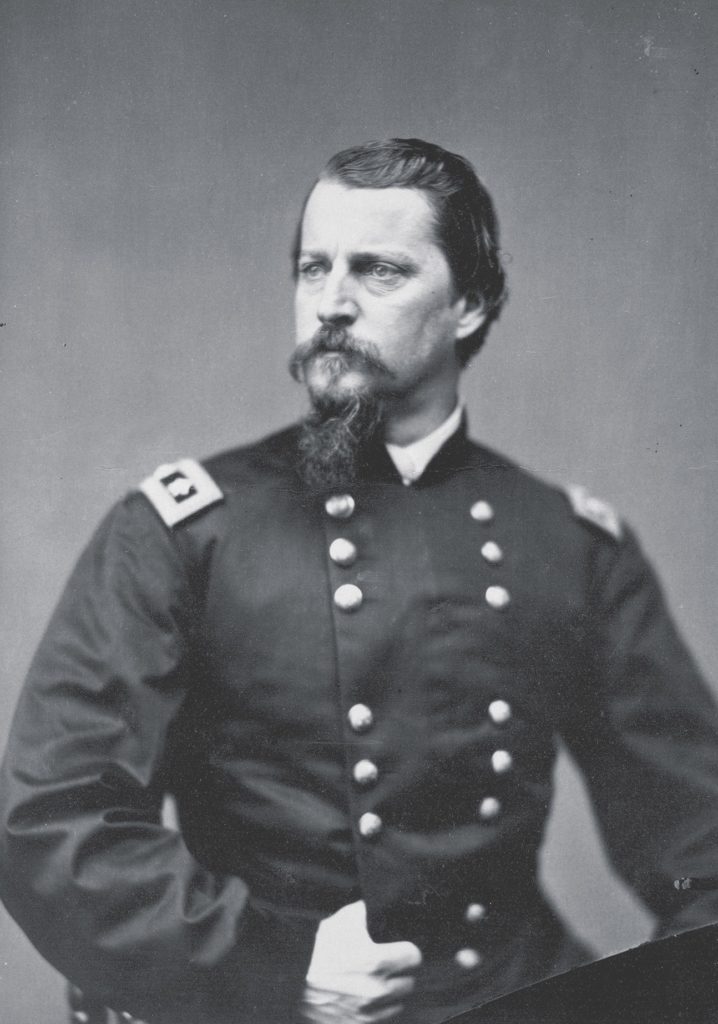

General Lewis A. Armistead’s arrival at the 11th Corps hospital at the Spangler Farm on the evening of July 3 likely coincided with the arrival of decades-long friend Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, commander of the 2nd Corps, at what was left of the 1st Division, 2nd Corps hospital at the Granite Schoolhouse on the Spangler property. Hancock had been wounded by fragments from his saddle when it was struck by a bullet during Pickett’s Charge.

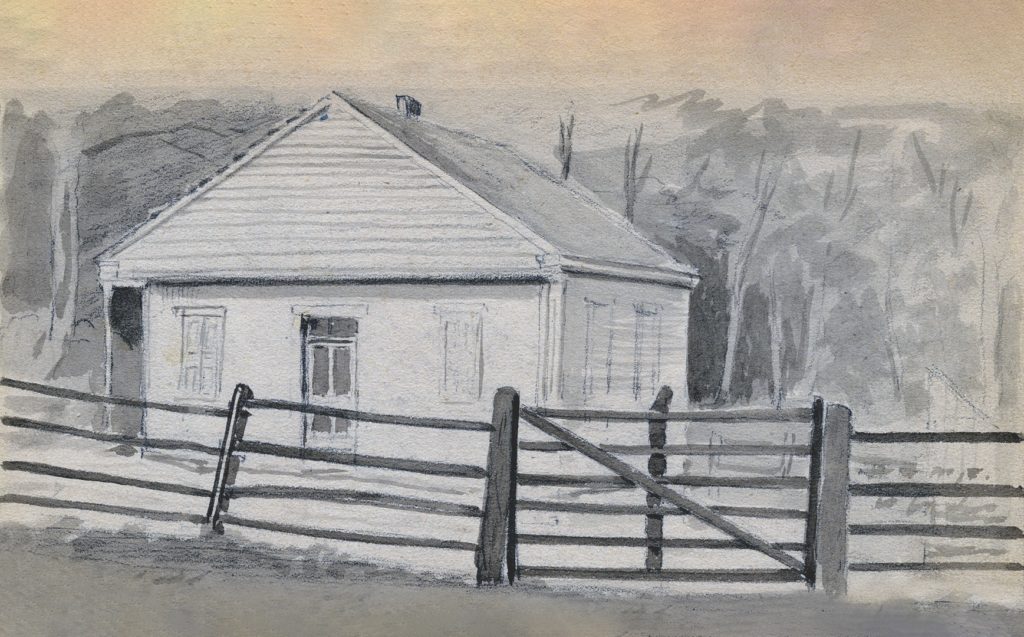

The schoolhouse had just opened in 1862 on a small plot of land the Spanglers had donated for such a purpose, no doubt in part because George Spangler was president of the Cumberland Township School Board

The road that serviced it, Granite Schoolhouse Lane, was also new, and neither it nor the structure were on the maps available to the Army of the Potomac. After the battle, Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams of the 12th Corps remembered that he had moved his men on the lane that he did not find “in the maps….My impressions are that it was a regular formed road.”

Hancock had to wait for an ambulance after he was wounded during Pickett’s Charge, and he wanted to issue orders and communications before being carried from the field. The Union general could have stopped at Granite Schoolhouse for further treatment or observation, even though most of the hospital had been moved farther to the rear by the time he arrived, out of Rebel artillery range. Or he could have halted there to send more communications. A monument at the end of Spangler lane discusses the likelihood these two dear friends were unknowingly on Spangler property at the same time and only a quarter-mile apart.

The schoolhouse was a major hospital for two days for men of the 1st Division of the 2nd Corps, which fought July 2 in the Rose Farm woods and the famous Wheatfield. This was the division commanded by Brig. Gen. John Caldwell that the Rev. Father William Corby granted general absolution to moments before the three brigades, including the Irish Brigade, plunged into deadly action. The division lost about 1,300 casualties in mainly one day of fighting, and many of those injured men were taken to the Granite Schoolhouse.

“The first Division caught the heaviest of the blow, many killed and wounded were the result,” said Granite Schoolhouse hospital Surgeon-in-Charge Dr. William Warren Potter, 57th New York, “many killed and wounded were the result, and the latter were now being brought to the hospital in great numbers.”

In addition to Hancock, another Union general was treated at the Granite Schoolhouse. Brig. Gen. Samuel K. Zook was examined there on July 2 for a massive chest wound. He had been struck on the “Stony Hill” just west of the Wheatfield. A Granite Schoolhouse surgeon quickly deduced Zook’s wound as mortal, the gaping hole in his chest was so large the doctor could see the general’s heart beating, and he was carried to a house farther behind the lines along the Baltimore Pike where he died on July 3. A monument on Wheatfield Road marks where Zook was mortally wounded.

Fifth New Hampshire commander Colonel Edward Cross died July 2 at Granite Schoolhouse after being mortally wounded on the opposite side of the Wheatfield from Zook. Cross Avenue between Devil’s Den and the Wheatfield bears his name.

During the battle, the land east and west of the school were mainly open fields mixed with patches of trees. Union infantry and artillery units used open spaces west of the school for bivouacs. Today, the area is heavily wooded.

The hospital had to be moved to near McAllister’s Mill on the Baltimore Pike on July 3 when Confederate overshots from the massive pre-Pickett’s Charge cannonade began to fall near the one-room schoolhouse.

Patient Lieutenant Charles Fuller of the 61st New York recalled on that afternoon his impending leg amputation was postponed when the “enemy began to drop shells that exploded in and about the locality. It was not a fit place to pursue surgical operations.”

Granite Schoolhouse was closed for health reasons by the commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1921 and torn down the same year. The hospital site is now largely forgotten, and most people likely can’t find the site today along Granite Schoolhouse Lane. No sign marks it like other division hospitals around the battlefield, and it’s on National Park Service land covered in thorns and underbrush. Only a few stones from the foundation of the Granite Schoolhouse remain today, but they are buried by almost 100 years of wear and tear and weather. –R.D.K.

Ronald D. Kirkwood is the author of Too Much for Human Endurance: The George Spangler Farm Hospitals and the Battle of Gettysburg (Savas Beatie, May 2019). His book contains the names, regiment, wound(s) and treatment for more than 1,400 men at the 11th Corps hospital.

This story appeared the April 2020 issue of Civil War Times.