One became the first victory of the war by an American ground commander. The other was far more personal.

The call came into U.S. I Corps headquarters in the Australian city of Rockhampton on a sleepy Sunday afternoon. It was late November 1942 and General Douglas MacArthur, Allied supreme commander for the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), needed the corps commander to stave off a debacle.

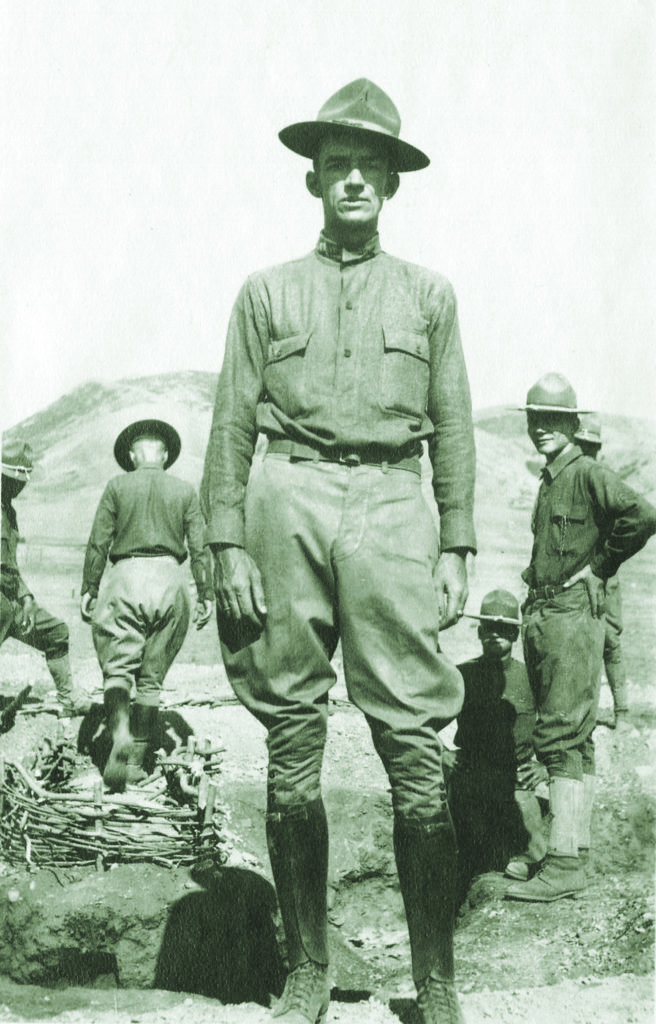

Newly promoted to lieutenant general, Robert L. Eichelberger, 56, had spent his entire life preparing for this sort of summons. The son of a prosperous Urbana, Ohio, lawyer who had pitted his children—especially the four boys—against one another in competition, Robert grew up thin-skinned, overly sensitive to criticism and personal slights. He was also an average, if not uninterested, student. But following an appointment to West Point, he found in himself a latent talent for soldiering. He also saw in a military career an opportunity to earn fame and status—a drive that stayed with him following the death of his father in 1906 when Eichelberger was a cadet.

By the time the United States entered World War II, Eichelberger, then a brigadier general, was serving as West Point superintendent, a job he referred to as “my Number One assignment from the standpoint of desirability.” Once, during a visit to his father’s grave, a friend heard Robert whisper to the tombstone: “You said I wouldn’t be appointed to West Point. You said I wouldn’t make the grade at West Point, and now I’m running the place.”

His ultimate goal, though, was to command troops in battle. With the war on, he requested a combat assignment and was placed in charge of the newly activated 77th Infantry Division, where he did such a fine job training the yet-to-ship-out troops that he was immediately slated for corps command and three-star rank. In August of 1942, he assumed command of I Corps, composed of the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions—the first two sizable U.S. Army combat units sent to Australia. But for the first several months, Eichelberger—finding himself consigned mainly to training troops in northern Australia—felt as though he was being treated “more like a lieutenant than a lieutenant general.”

When the call from SWPA headquarters, at last, came on that listless Sunday afternoon, he understood exactly what it meant. From I Corps headquarters, Eichelberger had been monitoring events on Papua—the eastern portion of New Guinea—where on its east coast, the 32nd “Red Arrow” Division was locked in a life-and-death struggle against Japanese invaders to capture a perimeter of interlocking fortifications and stinking swamps ringing the village of Buna.

It was midafternoon on November 30 by the time Eichelberger and members of his staff arrived at Government House—the rambling four-bedroom, one-story house in Port Moresby, on Papua’s western shore—where MacArthur had located his headquarters. Even before Eichelberger and his deeply trusted chief of staff, Brigadier General Clovis Byers, could settle into their rooms, they received a summons to meet with MacArthur and were ushered onto the veranda. MacArthur’s chief of staff, Major General Richard K. Sutherland—freshly returned from a meeting with the commander of the 32nd Division, Major General Edwin F. Harding, an old West Point classmate of Eichelberger’s—sat grim-faced at a desk, catching up on paperwork.

MacArthur paced around the veranda, lecturing rather than conversing, as was typical of him. “Bob, I’m putting you in command at Buna,” he told Eichelberger. “Harding has failed miserably. I want you to relieve Harding, Bob. Send him back to America, or I’ll do it for you. Relieve every regimental and battalion commander. If necessary, put sergeants in charge of battalions and corporals in charge of companies. Anyone who will fight. If you don’t relieve them, I’ll relieve you. Time is of the essence. The Japs may land reinforcements any night.”

While MacArthur was right to be concerned about the possibility of new Japanese landings, his consternation and impatience stemmed at least partially from personal reasons. He had already lost the Philippines. He had barely hung on to Port Moresby. Now his first offensive in the war was careening toward disaster. How much longer could he maintain the confidence of his superiors in Washington and the veneer of greatness among the American people? He felt enormous pressure to produce a victory and begin his long journey back to the Philippines.

MacArthur continued pacing and railing against the situation at Buna, then paused, looked at Eichelberger, and uttered fateful words: “That is the job I’m giving you. Bob, I want you to take Buna or not come back alive.” He pointed at Byers. “And that goes for your chief of staff, too, Clovis.”

It was a depressing order, one that stemmed from the dreariness and uncertainty of the situation. Eichelberger understood that Buna represented the golden opportunity of his career, the long-awaited chance to distinguish himself as a great battle captain and satisfy his lifelong yearning for notable achievement. In this personal sense, he and MacArthur were in the same boat—Buna was going to make or break both of their careers.

By the time General Eichelberger’s plane taxied to a stop later the next morning at the Allied airfield and supply depot at Dobodura, a few miles southwest of Buna, the putrid, moldy stench of Buna’s swamps had already assaulted his nostrils. Like any good commander, Eichelberger was determined to check out the front for himself. Dictated by the swampy terrain, Harding had divided his command into two main, noncontinuous regimental-size fronts. The Urbana sector, which he named for Eichelberger’s hometown, was on the western flank, in front of Buna village, where the Japanese had anchored their perimeter; the Warren front, named after the Ohio county Harding was from, was on the eastern flank.

At 9:30 the following morning Eichelberger, accompanied by Harding, set off for the Urbana front; he sent Colonel Gordon Rogers, his intelligence officer, and Colonel Clarence Martin, his operations officer, to inspect the Warren front. What Eichelberger saw stunned and angered him. There was no actual line, just confused clumps of frightened soldiers scattered around the jungle. While small groups manned forward fighting positions, scores more drifted to the rear. The few soldiers actually at the front would not go forward. Leaders were practically invisible. Weapons were corroding or unattended in the tropical climate. Patrols were almost nonexistent; men were even more afraid of the jungle than the Japanese. A sense of lethargy hung over them like a veil.

And the troops were in poor condition. They “complained of being hungry…and rightly, for they were not getting enough food,” one of Eichelberger’s aides recorded in a report that evening. “They were living among their own unburied dead.” The stench of corpses was overwhelming. “You could smell that for twenty-four hours, seven days a week, and you could taste it,” Tech 5 Claire Ehle later recalled.

As night settled over Dobodura, Harding visited Eichelberger’s tent and began to brief him on new attack plans. Eichelberger was polite but distracted. Instead of commenting on the plan, he mentioned the troubling nature of what he had seen that day. At last Harding blurted, “You were probably sent here to get heads. Maybe mine is one of them. If so, it is on the block.”

Eichelberger sighed and nodded, “You are right.” He pointed at Brigadier General Albert “Doc” Waldron, the thin, wiry division artillery commander who had moved heaven and earth just to get a few guns in place to support the push for Buna. “I am putting this man in command of the division.”

“I take it I am to return to Moresby,” Harding said.

“Yes.”

Without a word, Harding left the tent. Waldron followed and expressed his regrets, as did Eichelberger. Harding made no reply. Though the two old classmates ate breakfast together the next day, their relationship never recovered; in fact, it was the last time they ever spoke. Word of Harding’s relief spread through the division like a shock wave. “They can’t do this to you!” Major Chet Beaver, an aide, roared defiantly. “They can, and they did,” Harding replied matter-of-factly.

Eichelberger did the best he could to tamp down resentment among the Red Arrow soldiers for axing their leader. “There was some talk that I would be shot in the back by some of [Harding’s] men,” he later wrote. For two days he called a halt to all operations while he installed new leaders, restored unit integrity, planned a new offensive, fed the troops, clothed them properly, got them medical care, and restored their shaken morale.

Eichelberger discovered that there were huge quantities of food, ammunition, and medicine at Dobodura, in crates that had piled up uselessly at the airfield. He quickly alleviated this problem, setting up a more efficient supply system. Planes were unloaded with more reliability. Work parties were better organized. On December 3, the troops ate their first hot meal in nearly two weeks. Drinking water was fairly plentiful, though it had to be chlorinated by medics or engineers or with purification tablets before consumption.

All of this represented improvement for the Allied situation at Buna. But there was still the little matter of overrunning the Japanese defenders. At 10:30 a.m. on December 5, 1942, Eichelberger launched a new attack on both fronts. There was nothing subtle about the offensive. Air strikes by nine B-25 medium bombers, plus some artillery and mortar fire served as the softening-up bombardment—a paltry mix by the army’s later pre-attack standards. Like the struggle for Buna as a whole, it was really an infantryman’s small-unit fight, a frontal assault—but not in masses, since the thick jungle made this impossible.

“Our troops could not fight as units,” one operations officer later wrote, “but rather as individuals or in twos and threes.” At dozens of miserable places, small groups of American infantrymen went forward on the same trails and into the same swamps where previous attacks had failed. “There are Japs up ahead, but there also may be Japs behind me, and I’m sure as hell there’s a couple of them a few yards over to the side,” a rifleman at the front told a war correspondent. “We just keep looking for Japs, killing them, and pushing ahead.”

The troops still had few weapons beyond grenades and rifles with which to assault the well-camouflaged Japanese bunkers. Often the Americans did not see the bunkers until they were among them, pinned down by machine-gun and rifle fire, trapped like bugs on a spider web. “Realistically we found bunkers by losing men,” one survivor said. Another remembered, “The only place we could attack was in their line of fire.”

Japanese riflemen tied themselves to the tops of coconut trees and acted in a dual role as observers for their comrades in nearby bunkers and as snipers who picked off men as they tried to advance. Their exploding bullets scythed through helmets, throats, or abdomens. “If there was an opening in the jungle,” Sergeant Henry Dearchs, another infantry soldier, recalled, “the Japs didn’t shoot at the first guy. They’d let you all come in before firing.”

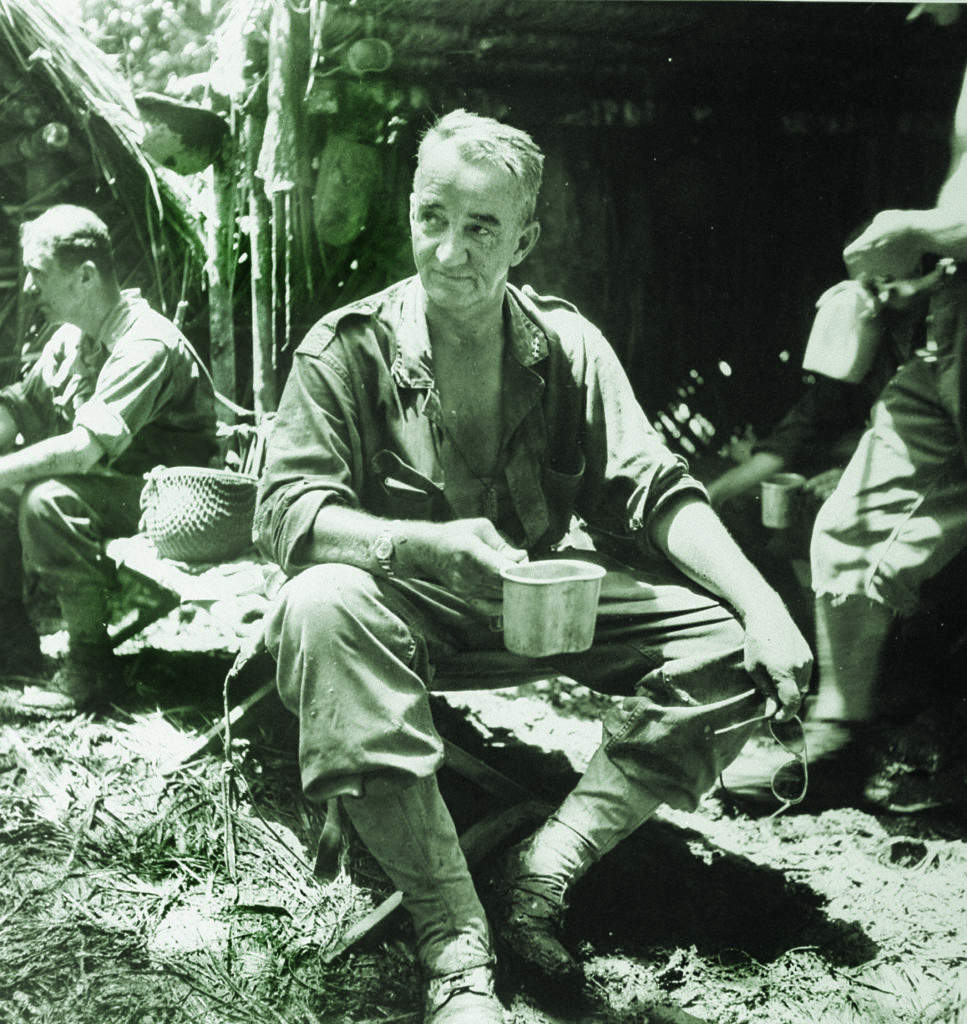

Like nearly everyone else, General Eichelberger experienced the horror of the sniper fire. True to form, he was right up front, leading the attack—all three of his stars displayed on the collar of his sweat-soaked fatigues. His entourage included Colonel Rogers and four others. Several carried Thompson submachine guns. At the Urbana front, they saw a group of soldiers take some fire within a few yards of their jump-off point and go to ground. Eichelberger, entourage in tow, strolled over to them and said, “Boys, we are going forward. Come with us.” They got up and followed, though undoubtedly some wondered if this old man with the stars was out of his mind. As long as Eichelberger led, the troops were willing to keep going.

The same was true when he later encountered members of three attacking rifle companies. While he led and cajoled, they slowly worked forward. Within a few minutes, they all became enmeshed in confusing, intimate duels with the unseen snipers. At one point, Eichelberger was pinned down for a quarter of an hour, bullets zipping by about four inches overhead, spattering everywhere around him. “Fifteen minutes, with imminent death blowing coolly on your sweat-wet shirt, can seem like a long time!” he later wrote.

Eichelberger’s run-in with the snipers was typical of what was happening all over the Buna perimeter. The Americans were putting pressure on the Japanese, inflicting damage on them, but significant forward movement was negligible. Lieutenant Robert H. Odell, in command of F Company, 126th Infantry, received a personal briefing from Eichelberger to take Buna village only a couple of hundred yards away, but, because of the Japanese bunkers and the terrain, the proximity to the objective did not matter as much as it otherwise might have. They had only 10 minutes to recon the area. “Well, off we went, and within minutes our forward rush had definitely and completely halted,” Odell wrote. “Of the 40 men who started with me, four had been…killed and 18 were laying wounded. We never had a chance, and that is all there was to it. Infantry can’t advance past pillboxes.”

There was one bright spot, though. A platoon from H Company, 126th Infantry, under the command of Staff Sergeant Herman J. F. Bottcher, 33, infiltrated past several enemy bunkers and made it to the beach between Buna village and Buna Government Station, a prewar Australian colonial outpost a few hundred yards farther east along the coast. For the first time, the Americans had breached the Japanese defensive line.

Soldiers of the Urbana front dubbed the narrow salient “Bottcher’s Corner.” In that perilous spot Bottcher’s platoon remained for nearly a week, periodically joined by other infiltrators, including Eichelberger on one occasion, with Bottcher patrolling back and forth to the American lines to bring up more supplies and reinforcements. A German-born anti-Nazi who had emigrated to the United States before the war, Bottcher performed like a man possessed—partly, according to Colonel Rogers, because Eichelberger had promised him American citizenship in exchange for honorable service. Thanks to Bottcher and his men, Buna village was cut off from the Government Station (and Bottcher earned not only his citizenship but also a field commission and the Distinguished Service Cross). The battlefield gain wasn’t much, but it did signify a more aggressive spirit in the American troops at Buna, and it created a serious wedge in the Japanese perimeter.

As the fighting petered out on December 5, Eichelberger decided that he would launch no more general attacks on either front. Better, he decided, to bring down his opponent by landing hundreds of little punches. The Buna battle had really boiled down to the stark reality that the Americans now had to annihilate the defenders, bunker by bunker, trench by trench, tree by tree, probably until they were all dead—an extermination duel that was nearly unprecedented in U.S. Army history. Eichelberger dubbed it “a military nightmare.”

But bit by bit, General Eichelberger’s attrition strategy began to work. He launched a series of small, tenacious attacks against the beleaguered enemy garrison at Buna village. While the attacks chewed up the remnants of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry—Lieutenant Odell’s F Company had only 38 soldiers left—they inflicted hundreds of casualties on the Japanese. A new battalion from the 127th Infantry relieved the 126th to finish the job.

Spooked by cryptic reports of reinforcement-laden Japanese convoys and impatient for quick results, MacArthur on December 13 prodded Eichelberger: “However admirable individual acts of courage may be; however splendid and electrical your presence has proven, remember that your mission is to take Buna. All other things are merely subsidiary to this. No alchemy is going to produce this for you; it can only be done in battle and sooner or later this battle must be engaged. Time is working desperately against us.”

Unbeknownst to MacArthur, even as he wrote to Eichelberger, the Japanese were evacuating Buna village. Spurred on by Eichelberger, troops from the 127th claimed the village on the morning of December 14. The place was little more than an odorous mishmash of wrecked huts and shattered coconut trees, strewn with the detritus of discarded clothing, empty food cans, ragged bits of uniform, and bloody bandages.

Five days earlier, Australian troops fighting in the region had taken fortified Gona a few miles up the coast to the west, where they buried 638 Japanese corpses. With the victory at Buna, the Allies had now driven a permanent wedge in the Japanese defensive perimeter. The Japanese defenders were outnumbered, penned into separate areas, and cut off from adequate supply and support. When MacArthur found out that Buna village had fallen, he was jubilant. He sent Eichelberger a laudatory telegram: “My heartiest congratulations. Under your magnificent leadership, the 32nd Division is coming into its own. Well done, Bob.”

When MacArthur thereafter realized that the capture of Buna village did not necessarily mean the imminence of final victory, he urged Eichelberger to mass his forces for one final climactic attack against Buna Government Station and the rest of the Japanese defensive perimeter. Eichelberger knew that the mass offensive MacArthur envisioned was an impossibility. Whether MacArthur liked it or not, Eichelberger’s deliberate approach was appropriate to the circumstances, and probably the only realistic course of action.

But although victory now seemed probable, Eichelberger was well aware that, as he put it, “the fighting was under conditions that are indescribable.” The monotonous 90-degree heat and high humidity sapped energy and made it difficult to stay hydrated. Even with adequate food, men lost weight—usually between 10 and 20 pounds in just a few weeks. One husky 230-pound man lost 70 pounds after a month in the area. Filthy and tired, the men had a shadowy appearance. “They were gaunt and thin, with deep black circles under their sunken eyes,” Sergeant E. J. Kahn wrote. “They were clothed in tattered, stained jackets and pants. Few of them wore socks or underwear. Often the soles had been sucked off their shoes by the tenacious, stinking mud.”

Mosquitoes seemed to breed by the second in the moldy swamps. Leeches preyed on the ankles and legs of anyone who waded through the water. “Our shoes were full of blood, and those sores never went away,” one of the afflicted wrote in his diary. Prodigious rains, usually falling in torrents at night, soaked everyone and everything. One-day totals of six to 10 inches were not uncommon. “No one could remember when he had been dry,” Eichelberger wrote. “The feet, arms, bellies, chests, armpits of my soldiers were hideous with jungle rot.”

Of the 10,685 combat soldiers mustered by the 32nd Division’s three infantry regiments, some 8,286 men were treated for diseases—primarily malaria, dengue fever, dysentery, and scrub typhus—a figure that outnumbered combat casualties by a factor of more than three to one. Many other cases went unreported, as fever-ridden soldiers refused evacuation or simply kept going, unaware they were sick. In the midst of it all, General Eichelberger tried to hold together his army and destroy the Japanese through his attrition plan. Often he wrote to Sutherland, or even MacArthur himself, pleading for forbearance. “I know how anxious General MacArthur must be,” he told Sutherland in one typical missive. “Tell him to please be patient.”

Eichelberger continued to spend most of his days at or near the forward positions. Casualties among his retinue inevitably piled up. On December 15, General Byers got shot in the right hand by a Japanese sniper and had to be evacuated to Australia—a tremendous loss, as the two were veritable kindred spirits. Days later, Colonel Rogers took bullets in both legs. Eichelberger breathed a sigh of relief when he found out that both would recover.

For the general, Buna represented a professional crossroads of sorts. He knew that his entire military career had boiled down to whether he succeeded or failed. For someone with Eichelberger’s deep yearning for achievement and distinction, failure was not an option. While he was unwilling to squander lives in pursuit of his military ambitions, there was nonetheless a single-minded ruthlessness about him. Instead of replacing Byers with another division commander, he simply filled the role himself. He continued to fire or reassign commanders without hesitation. He occasionally browbeat officers whom he considered weak or ineffective.

“When his reputation was at stake, as it was at Buna, and his career hung in the balance, he was like a caged lion,” Colonel John E. Grose—who commanded the Urbana force and had a love-hate relationship with Eichelberger—later told an interviewer. Resentful 32nd Division soldiers dubbed him “Eichelbutcher” and called the growing temporary cemetery near Buna village “Eichelberger Square.”

Prodded by Eichelberger, American soldiers day by day attacked and killed tenacious Japanese defenders at such places as the Duropa Plantation, the Triangle, Government Gardens, and Simemi Creek. Each fight was a struggle to the death. In almost all the small-unit actions, the two sides fought within a couple hundred yards of each other. Often they fought at handshake range. In hopes of luring the Americans into an ambush, Japanese soldiers shouted, “Hey, we give up!” or “Hey, we surrender!” only to gun down anyone who left cover. In response, angry American infantrymen refused to take prisoners.

Once the attackers identified the location of a bunker, one group sprayed the surrounding trees with fire to eliminate snipers, while the other attempted to get close enough to kill anyone in the bunker. According to one U.S. Army report, “The fighting frequently resolved itself into distinct small engagements to capture individual bunkers…a very difficult operation…flanking movements were almost impossible.” Even when the Americans overran a bunker, they had to make sure that Japanese survivors did not infiltrate back into them. “It is important for the attacking force to be certain that all enemy personnel in a ‘destroyed’ bunker are dead,” one junior officer advised. The process was bloody, deliberate, and rudimentary.

The prize for each typical advance was usually a couple of hundred yards of stinking swamp, jungle, or coastal coconut palms. Engineers laid down planks or built footbridges to help the attackers ford the noxious waters that protected the Japanese positions at the island and other similar spots. All too often, the lead troops were shot to pieces as they attempted to advance through such fatal funnels. Still, each day the Japanese-held perimeter slowly shrank as the Americans ate away at them, and both sides neared a breaking point.

Eichelberger himself was hardly immune to the ravages of attrition. Weary and frustrated at the deliberate pace of operations, he raged in one letter to Sutherland, “I am trying to kill the little devils in any way possible,” including blanketing their lines with white phosphorus. “I hope the little devils get their tails burned.” When a Christmas Eve attack on the Urbana front failed to eliminate the remnants of Japanese resistance, he admitted the next day to MacArthur, “I think that the all-time low of my life occurred yesterday.”

What Eichelberger did not know was that the “little devils” were nearly finished. Wasted away from starvation and the exhaustion of fighting so desperately for weeks, few Japanese soldiers possessed enough physical endurance to resist as they once had.

At last, on January 3, 1943, Eichelberger’s men took Buna Government Station, effectively ending the battle, though isolated groups of enemy soldiers held out for a few more days. The tired American survivors picked through the ruins of their hard-won objective. “It was a scene of desolation,” F. Tillman Durdin of the New York Times wrote. “The half-dozen buildings were in ruins, and some were still burning. Trees were bedraggled. Shells pitted the area. American troops everywhere. Enemy dead littered the beaches; others lay inside the bunkers.”

Buna ended in the manner of nearly every subsequent Pacific Theater battle: not with a formal surrender or acknowledged conclusion of battle by either side, but mainly by the obvious course of events and a declaration of victory from American commanders. “The Papuan campaign is in its final closing phase,” MacArthur’s headquarters stated triumphantly. “The Sanananda position [the final Japanese-held perimeter in the area] has now been completely enveloped. A remnant of the enemy’s forces is entrenched there and faces certain destruction.” This fact was true. But it took several more hard weeks of fighting by Australian troops and the 41st Infantry Division’s 163rd Infantry Regiment, plus many more agonizing days of frontline-combat command for Eichelberger, before the Allies on January 22 could claim to control Sanananda, thus ending the Papua campaign. Out of about 17,000 Japanese troops in the battle, some 13,000 were dead. Allied gravediggers buried 7,000 of them; the rest had either been interred by their comrades or simply left to rot anonymously in New Guinea’s cruel climate.

The campaign cost the lives of 2,165 Australians and 930 Americans. Roughly one out of every 11 Americans committed to battle at Buna did not survive. Another 2,100 GIs were wounded. The battle casualty rate was nearly one in four. Eichelberger later estimated that half the riflemen were either killed or injured. Many thousands more soldiers were, of course, stricken with disease, bringing the overall casualty rate from battle and disease, factoring in replacement troops, to well over 100 percent.

The 32nd Division was shattered and had to be completely rebuilt. It would be another year before the division was ready to go back into combat. As a result, American ground combat capability in SWPA was substantially limited for most of 1943. The U.S. Army’s official historian quite properly termed the campaign “one of the costliest of the Pacific war.”

Eichelberger returned to Rockhampton on January 26, 1943. Exhausted, weakened by weight loss and stress, he nonetheless felt enormously proud of what he had accomplished. “It is difficult to convey to the reader the immense relief, the feeling of freedom, the outright joy, that came with victory,” he later wrote. Eichelberger was the first American ground combat commander in World War II to consummate a victory, and he had done it under extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

But just as Eichelberger had once looked to his skeptical father for praise and recognition, he now expected grand accolades from MacArthur. Though the SWPA commander did release Eichelberger’s name to the media as I Corps commander and forwarded a note of congratulations, he was otherwise oddly cool to the man who had done more than anyone else to salvage victory at Buna. He awarded Eichelberger the Distinguished Service Cross—but, in the citation, failed to differentiate his actions from several other recipients who had never even visited the front.

The release of Eichelberger’s name generated a worldwide wave of favorable stories with headlines like the Philadelphia Inquirer’s “General Eichelberger Helps Erase Defeat of Bataan.” But his overnight fame did not sit well with his boss. In a bizarre and awkward meeting, MacArthur made a veiled threat to bust Eichelberger to colonel because of the articles and send him home. Chastened but angry, Eichelberger did all he could to limit his exposure to the media. “I would rather have you slip a rattlesnake in my pocket than to have you give me any publicity,” the lieutenant general told an academy classmate who headed up the War Department’s public relations branch.

These slights might have been nothing more than a mere annoyance to a less sensitive and proud man than Eichelberger. The lieutenant general was especially angry at a sentence from a communiqué MacArthur released soon after the conclusion of the Papua campaign: “There was no necessity to hurry the attack because the time element, in this case, was of little importance.” For a commander who had repeatedly risked his life and expended the lives of many other good men because his chief told him that time was of paramount importance, the statement was hard to take. “I was feeling decidedly hurt,” Eichelberger later admitted. He formed the opinion that MacArthur and those around him were far too detached from the real fighting to understand it in any meaningful way. In a letter to his wife, Eichelberger contemptuously referred to MacArthur as “the great hero” who, although not seeing Buna before, during, or after the fight, permitted press articles saying that “he was leading troops in battle.”

The notion that MacArthur personally led soldiers in action at Buna solidified among the American public—a myth that bothered Eichelberger on many levels, especially from the standpoint of personal integrity. More than anything, he felt disappointed in MacArthur and hurt by his actions. Indeed, the aftertaste of Buna had become unpleasant. “The battle of personalities growing out of Buna was almost as important as the actual fighting,” he commented. Buna was the halting first step that launched MacArthur’s drive back to the Philippines and enduring fame; for Eichelberger, Buna marked the start of a remarkable run as a combat commander—one of America’s very best—from New Guinea to the Philippines. Unlike his iconic chief, though, posterity has largely forgotten him. ✯

This story was originally published in the October 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.