The Confederate president’s trial was bungled from beginning to end

Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez is both a Civil War historian and a trial attorney in Austin, Texas. That background helped him delve into the details of each side of Jefferson Davis’ treason trial. Although the political head of the Confederacy was captured in 1865 and charged with treason in 1866, he spent only two years in captivity, and the charges were ultimately dropped. Icenhauer-Ramirez tracks the case at every turn in his recent book Treason on Trial, discovering shocking irregularities in the prosecution of Davis and the complicity of Chief Justice Salmon Chase in impeding the progress of the case.

CWT: What was Jefferson Davis imprisoned for?

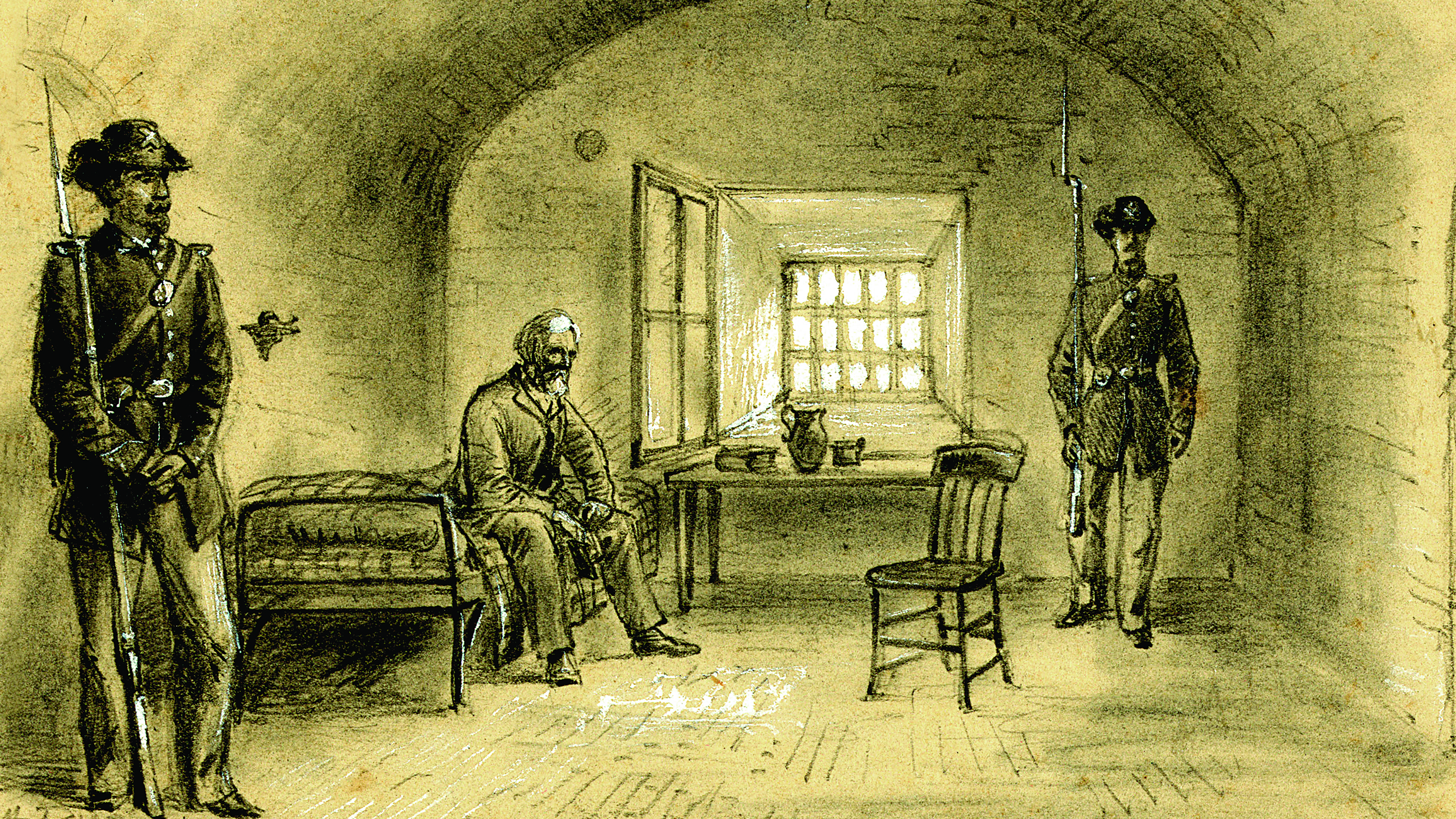

RIR: Once Lincoln was murdered, the people that were closest to Lincoln believed that Davis had a hand in it. I think if they had come up with a strong link to the assassination, he would have been tried for the murder by a military tribunal, but they couldn’t establish it conclusively. He was placed in prison and indicted for treason, something that was obvious as a charge.

LSU Press, 2019, $55

CWT: Talk about Virginia attorney Lucius Chandler, who wrote the treason indictment.

RIR: Chandler was the U.S. district attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, an appointed attorney. But the reason he was appointed had nothing to do with his skill level and everything to do with the fact that he was one of the few attorneys in the Eastern District who had been loyal to the North. Chandler, a transplanted Yankee, had remained loyal to the North, but he had no trial skills and really did not have the temperament or even the interest in being a trial lawyer.

CWT: You found something astounding in the Davis indictment.

RIR: A book about Aaron Burr had a copy of his indictment for treason and I saw that the language was exactly the same as the Davis indictment. Chandler just substitutes Davis’ name for Burr’s and that indictment stands for a couple of years in the case. When Attorney General William Evarts finds out that Chandler has not redrafted the indictment, he is livid. It is inconceivable that a well-trained prosecutor would think he could go to trial with that indictment.

CWT: Talk about the challenge of trying Davis in Virginia.

RIR: The U.S. Constitution says that treason will be tried in the location where it was committed. To be true to the Constitution, they’ve got to try him in Richmond. That’s a terrible spot for the federal government to try the president of the Confederacy. Not only because the jury pool is going to be tainted against the federal government but if you find people who are loyal to the Union, to try the Confederate president, there’s going to be the intimidation factor, especially for African Americans. That’s very real in the South after the Civil War.

CWT: There was also resistance from Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon Chase.

RIR: As Lincoln said, Chase got the presidential bug, and once you get it, you don’t lose it. His circuit happened to include Virginia, where he could go down and try cases. The last thing he wanted to do was alienate the people in the returning states. He knew this was going to be very divisive and kept it from being tried for a good long while and undermined the prosecution once it looked like it might actually go to trial. He privately insinuated to one of the defense lawyers that the 14th amendment would shield Davis from prosecution. There are signs that everybody knows what Chase is doing is improper, but he’s doing it anyway.

CWT: Would losing a treason trial against Davis bolster the legitimacy of secession?

RIR: I do not think so. But Richard Henry Dana Jr., one of the prosecution’s lawyers, is convinced that Davis’ attorney, Charles O’Conor, is going to say secession is legal, and, if secession was legal, Davis could not have committed treason. Occasionally, lawyers lose faith in their ability to win a case and begin to pitch ideas against trying it, in the hopes that their client will agree in its futility. Their client of course, was Andrew Johnson.

CWT: Andrew Johnson had made a campaign pledge to prosecute Davis.

RIR: Johnson never forgave Davis for slights toward him in the Senate, and he goes into the 1864 election campaigning that treason needs to be made odious. He thought the South’s leadership had led the good people of the South into a horrendous war. He thought the aristocratic leadership of the South had committed treason and he wanted people hanged for that. After the war, the Radical Republicans think Johnson is going to be more likely to hang people than Lincoln would have been. But when they began butting heads over how Reconstruction should proceed, Johnson is faced with the choice of either losing the support of the Radical Republicans and having no real political support, or moving over to the Democrats and working with them, and that’s what he chooses to do. The Democrats had no interest in trying Davis. For several years after the war, Johnson was interested in trying Davis. But I think by the time he gets impeached, he has bigger fish to fry.

CWT: In February 1869, the case is dismissed. What happened?

RIR: The prosecution was convinced that it’s going to be useless to try Davis. If they lose, it will look really bad for the feds. If they convict him, it will look like retribution rather than a just punishment. Attorney General Evarts solicits a letter from Richard Henry Dana recommending that the case be dismissed. When he finally presents it to the president, Johnson allows the case to be dismissed. Davis is in Europe and the case just fizzles. The people driving the case early on were the people that loved Lincoln like Edwin Stanton and Joseph Holt. But they begin to leave the government, and more people take office who have no interest in prosecuting Davis.

CWT: The delay in prosecution allowed the case to wither on the vine.

RIR: Davis’ reputation seemed to rise the longer he remained in jail. He became a martyr, and his embracing of the role of martyr was something that played into the Lost Cause myth. Early on, with the right prosecutor and the right judges, I think that the federal government likely could have gone to trial. Johnson would have wanted them to go to trial. But it just lingers and lingers and lingers. And Davis, charged with a capital offense, is out on bond. That’s an acknowledgement that you’re not really very dangerous. It was really the individuals who had their hands on the case who put it in a spot where it just didn’t make sense to try it.

This story appeared in the December 2019 issue of Civil War Times.