‘Dangerous’ Federalist Chase’s 1805 trial illustrates pitfalls of Trump ouster drive

DEJA VU

SINCE DONALD TRUMP’S election, his most passionate opponents have been transfixed by the vision of impeaching him. Website ImpeachDonaldTrumpNow.org appeared as the inaugural confetti was being swept up.

Trump’s Russophilia looked for months as if it might supply the legal MacGuffin. Former CIA director John Brennan declared Trump’s performance at a 2018 press conference with Vladimir Putin “imbecilic,” “treasonous,” and beyond the threshold of high crimes and misdemeanors. Once the Mueller report found no collusion, impeachers shifted focus to Trump’s tax returns, said to be as ugly as a yeti; they are certainly as elusive. In March The New Yorker, blue America’s Weekly Reader, ran a think piece titled “The Pros and Cons of Impeaching Trump.” To many New Yorker readers, the big reveal will be that there are cons. (See also: “Impeachable Offenses: How Hight the Crime.”)

Two presidents, Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, have been impeached, but not removed from office (Check out “How Andrew Johnson’s Fiery Campaign Led To Impeachment.”) A third, Richard Nixon, resigned when release of the “smoking gun” tape made it certain he would be both impeached and canned. A look at impeachment history shows its allure—and its pitfalls.

Impeachment is the first step, comparable to indictment, in the trial of a public official by a legislature. Once the alleged perpetrator has been impeached, members of the legislature vote whether to convict and remove from office. After removal, ordinary criminal procedures and penalties may apply.

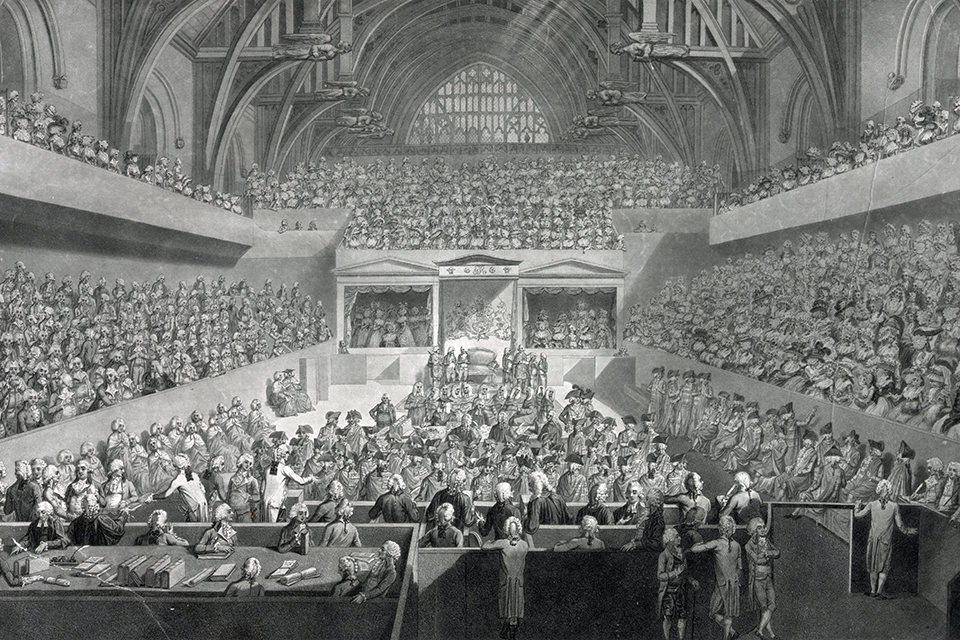

The most famous impeachment in Anglospheric history, which set the tone for all the rest, was the trial late in the 18th century of Warren Hastings. Hastings had built in India an empire to replace the one imperial colleagues were losing in America. He played rough, though, allegedly overtaxing his subjects, waging needless wars, even sanctioning judicial murders. His trial before the House of Lords, with the House of Commons prosecuting, was long—1788-95—and lurid. The greatest orators in the Commons competed to denounce the defendant. Hastings’ deeds, wrote one historian, made Edmund Burke’s blood “boil in his veins.” Irish satirist and Whig MP Richard Brinsley Sheridan delivered a five-hour harangue hailed as the best speech ever delivered.

Despite the onslaught of eloquence, Hastings presented enough character witnesses that the Lords cleared him. Britons remembered not the verdict, but the fireworks. Who would not want to boil and declaim alongside Burke and Sheridan? During Thomas Jefferson’s first term, an American prima donna would have his chance.

The election of 1800, which put Jefferson in office, had been a blue wave, giving both houses of Congress as well as the White House to Jefferson’s Republican Party. Only the judiciary, with the Supreme Court at its summit, remained in the Federalists’ otherwise defeated hands. Impeachment seemed to offer a chance at a clean sweep.

The Constitution gives the House the power to impeach, the Senate the power of trying and, on a two-thirds vote, removing from office. “All civil officers,” including the president, vice president, and federal judges, can be impeached for treason, bribery, or other “high crimes and misdemeanors.” A Jefferson ally, Senator William Branch Giles (R-Virginia), thought impeachment could be a simple matter of good housekeeping—“nothing more,” he told fellow senator John Quincy Adams (F-Massachusetts), than Congress saying, “You hold dangerous opinions….We want your offices, for the purpose of giving them to men who will fill them better.”

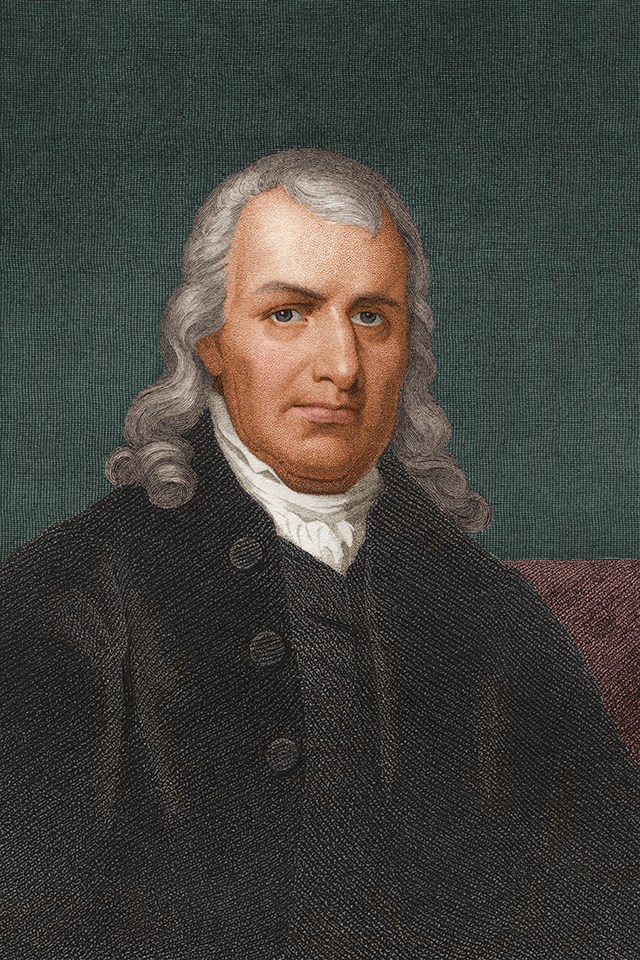

The most dangerous Federalist then on the bench, in Republican eyes, was Justice Samuel Chase of the Supreme Court. Chase, a Maryland patriot, had signed the Declaration of Independence. He also had bullied Quakers for their pacifism and tried to corner the flour

market during a wartime shortage. His record on the high court, where George Washington had deposited him in 1796, was similarly mixed. Chase had a sharp legal mind, but he also waded into political fights. In 1800 he had presided over the trial of journalist James Callender, then raking muck on behalf of the Republicans; later he was to develop an interest in Jefferson’s sex life. Callender was being prosecuted under the Sedition Act for maligning then-President John Adams. When Callender’s lawyers told the jury it could pass judgment on the Sedition Act itself, Chase said it could not—whereupon the defense attorneys stormed out of his courtroom, crying bias.

In May 1803, Chase went further, telling a Maryland grand jury that Republican policies would lead to “a Mobocracy, the worst of all possible governments.” President Jefferson, piqued, wrote a friendly congressman: should Chase’s “extraordinary” remarks “go unpunished?” In the Republican Party, for Jefferson to ask the question was enough. In January 1804 the House formed a committee to consider Chase’s conduct. At year’s end, he was impeached for his conduct of the Callender trial, his comments to the grand jury, and other alleged offenses. If Chase went down, Adams wrote in his diary, “the whole bench of the Supreme Court” would go next.

The House’s lead prosecutor, and America’s answer to Burke and Sheridan, was Representative John Randolph (R-Virginia), 31. Roanoke native Randolph, a cousin of Jefferson, had glimmers of his Brit predecessors’ star power: at his best he could be tart or eloquent, funny or ferocious. At his not-infrequent worst, he waxed obnoxious, overbearing and gassy. His voice had never broken. Fans found its high pitch melodious; critics, grating. A big drawback for his assignment: he was no lawyer.

The trial began February 4, 1805. The Senate chamber was arranged to resemble the House of Lords. Out went senators’ chairs, replaced by benches covered in crimson baize. Members of the House and ordinary spectators sat on benches covered in green. It seemed at first as if Chase, who was turning 64, would be made to stand throughout his ordeal, but he finally was granted a chair.

Once the trial began, Chase’s prospects looked up. As a defense team he had five top-notch lawyers, headed by his home-state attorney general. Some witnesses called to condemn him actually helped his case: a juror from the Callender trial testified that Chase “wished the prisoner to have a full hearing.”

Randolph was assisted by six congressmen. He and his team wasted time on trivialities—had Chase, outside court, called Callender “damned”?—and made mistakes in law. Bogged down, Randolph lost heart. His summation at the end of the month was a mess, punctuated by sobs, groans, apologies for misplacing his notes, and pauses to collect his thoughts. The speech shared with Sheridan’s and Burke’s only length: two and a half hours.

March 1 was the day of decision. The Senate had 25 Republicans and nine Federalists—enough, if everyone toed his party’s line, to remove Chase from office. Uriah Tracy, an ailing Federalist from Connecticut, had himself carried into the Senate chamber on a cot should his vote be needed. It wasn’t: Republicans unpersuaded by Randolph’s antics joined a solid Federalist phalanx to acquit Chase on every charge against him.

Jefferson would continue to quarrel with Federalist judges. But he never again used impeachment as political pest control. So it has remained. Judges have been removed, and Richard Nixon driven from office, for specific crimes. However, impropriety, manufactured offenses, and general I-hate-you do not make the grade. A president’s enemies should spend their time planning to beat him at the polls, not drafting articles of impeachment.