During World War II, the legendary writer sailed the Caribbean aboard the Pilar searching for U-boats

It is eerily quiet the day I arrive at Cayo Guillermo, a small tropical island in the Jardines del Rey archipelago off Cuba’s northern coast. The Covid-19 pandemic has decimated the country’s tourist industry, and most of the hotels are closed and empty. The newly constructed Grand Muthu is the only place in business, its 500 rooms accommodating just 26 guests. I am one of them.

It is my 25th visit to Cuba, but the first time I’ve stayed on Cayo Guillermo. I don’t have much choice. During the first phase of its post-Covid reopening, the rest of the country is still sealed off. Yet, with a copy of Ernest Hemingway’s Islands in the Stream stuffed in my bag, I have an ulterior motive.

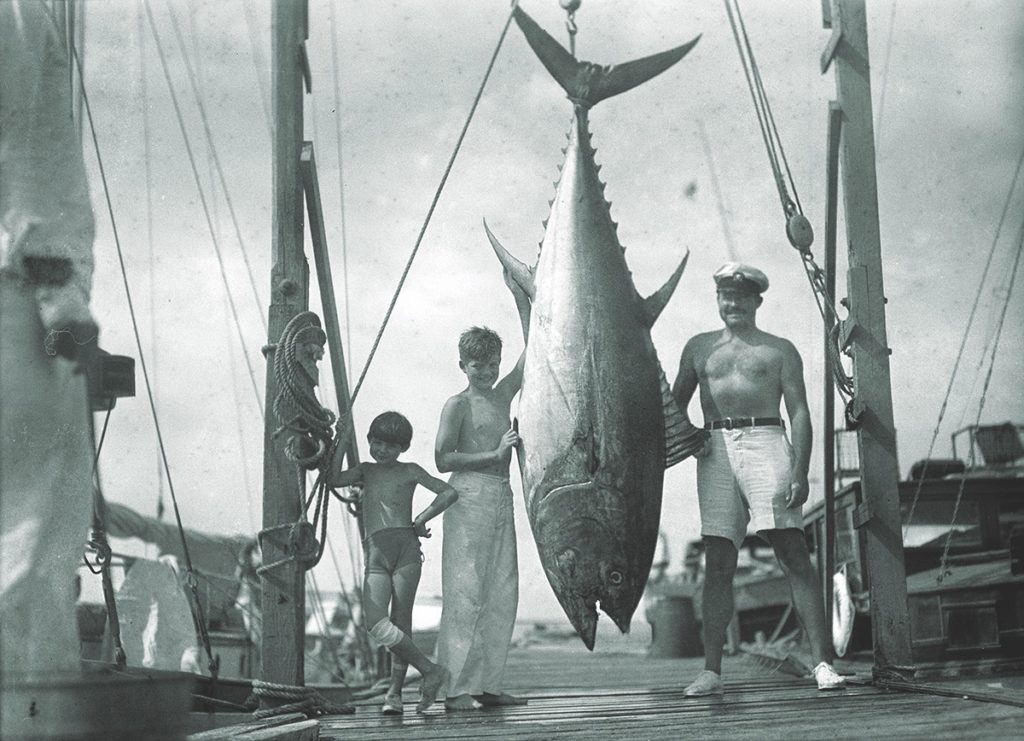

This was where “Papa” Hemingway came to hunt for German U-boats during World War II. Accompanied by a motley crew of fishermen, barflies, and semiretired players of pelota, a Basque court sport, he navigated his boat, Pilar, around Cuba’s wild northern cays. Outwardly a fishing vessel, Pilar secretly carried grenades, machine guns, and rocket launchers. It was an experience Hemingway fictionalized in his posthumously published novel Islands in the Stream. But, like so many Papa stories, the truth often gets confused with the legend.

It’s hard to avoid Hemingway in Cuba. The ghost of the nation’s second-most revered Ernest—after Ernesto “Che” Guevara—is everywhere, from El Floridita, the Havana bar where he allegedly once downed 13 double daiquiris in one sitting, to his book-lined former home, Finca Vigía, where you can look in through the windows at a 1950s freeze-frame of Papa’s life.

Cayo Guillermo is a newer lure. Until the early 1990s, the cay was uninhabited, but a subsequent hotel-building spree designed to draw in sun-deprived tourists has drastically altered its appearance.

Today, the five-square-mile cay with its briny mangrove swamps and resident flamingos supports nine all-inclusive resorts and vigorously markets its Hemingway connections. Among the soft, sandy beaches and limestone headlands, there’s a Hemingway shopping mall and a wooden Hemingway jetty. On the bus from the airport, I spot three statues of the writer adorning the bridge that connects Guillermo to Cayo Coco. Later that afternoon, I stroll across to Guillermo’s main beach, a blonde beauty named Playa Pilar after Papa’s fishing-vessel-turned-spy-boat.

Crowded with tourists in more normal times, the beach is empty. Enjoying the silence, I look out to sea where nearly 80 years ago Hemingway, armed with booze, bait, and bazookas, sailed clandestinely on the Pilar searching for German subs.

The U-boat threat was very real in Cuban waters during World War II. The country had declared war on Germany on December 11, 1941—the same day as the United States—and had quickly been drawn into the Battle of the Atlantic, then going through a protracted spike.

By the spring of 1942, German U-boats were sinking around 15 Allied boats a month in Cuban waters. Short on firepower, the U.S. Navy appealed to local yachters, offering them hard cash to refit their boats with weapons. For Cuba’s most famous resident fisherman, it was an opportunity too good to miss.

Equipping Pilar as an armed spy boat appealed to Hemingway’s sense of adventure. Craving action after returning to Cuba from reporting on the Spanish Civil War, he imagined himself fighting the curse of fascism and contributing positively to the American war effort. By posing as an innocuous fishing vessel, Pilar would dupe German U-boats into an unguarded approach and then—hey presto—unload the heavy ammunition.

If the mission sounded far-fetched, it was. It was hard to fancy Pilar’s chances against a torpedo-brandishing German submarine sporting an 88mm deck gun. According to historian Nicholas Reynolds in his 2017 book, Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy, even Hemingway later admitted that the whole operation was “just so improbable” that no one would ever believe it had happened.

Notwithstanding, the U.S. ambassador to Cuba, Spruille Braden, rubber-stamped the seemingly suicidal mission, offering the writer munitions, radio gear, and promises of secrecy. Braden, who had already worked with Hemingway on a short-lived Cuban spying caper called the “Crook Factory,” was supposedly so impressed with Papa’s patriotism and sleuthing abilities that he circumvented normal regulations to back him.

Other observers, including Hemingway’s wife at the time, Martha Gellhorn, weren’t so confident. Gellhorn was a fearless war correspondent anxious to get back to the conflict in Europe after serving in Spain. According to Reynolds, she saw her husband’s over-enthusiastic U-boat tracking as “just a way for Pilar’s skipper to get scarce wartime fuel for his boat so that he could fish and drink with his friends.” Undeterred, an adamant Hemingway gathered his crew and set off on what he christened “Operation Friendless.”

To get a feel for Hemingway’s U- boat adventures, I decide to hit the water myself. I go down to the beach in front of my hotel and persuade an underemployed Cuban boat operator to take me out fishing. Thirty minutes later I am bobbing half a mile offshore on a small sail-powered catamaran feeling distinctly Hemingwayesque as I try to reel in a stubborn barracuda.

As I look back at pancake-flat Guillermo, lined these days with hotels, I recall the dramatic climax of Islands in the Stream. After days spent tracking a stricken German submarine, the American protagonist, Thomas Hudson, and his crew apprehend the abject survivors in a mangrove-choked channel behind Cayo Guillermo. There’s a shootout and Hudson—a typically flawed Hemingway hero—is mortally wounded.

For Hemingway, the reality wasn’t quite as heroic as the fiction. In 1942–43, the writer spent the better part of a year on his so-called war cruises but only ever spotted one potential U-boat—from a distance. Trying to get close enough to dispatch his bazookas, Hemingway gave chase only for the mystery vessel to promptly speed up and disappear.

And that was that. Aside from writing up ship logs and sending coded radio messages back to Havana, Hemingway and his crew spent the remainder of their lengthy patrols playing cards, lobbing grenades at marker buoys, and getting increasingly bored—and drunk.

By the summer of 1943, the war was turning against the Axis and the U-boat threat was waning. A coded message summoned Hemingway back to Havana. Operation Friendless was over.

While the U-boat tracking might have been fruitless, Hemingway had been right about the fishing. During my brief catamaran cruise off Guillermo, I catch four barracudas in less than two hours. After the boat operator drops me back on the beach, I wander past the wooden Hemingway jetty down to Hemingway Bridge to get a closer look at the statues. Two depict him in fishing poses. A third shows him raising a hand in greeting. Fish dart through the shallow channel beneath the bridge while a couple of hopeful fishers stand above, casting lines from cheap-looking rods.

Despite a 60-year U.S. trade embargo, Cubans still love the great American wordsmith. Havana’s main marina is named in his honor, and every state-run travel agency worth its salt offers a definitive Hemingway tour.

Meanwhile, biographers remain split on the usefulness of Hemingway’s Cuban war efforts. Reynolds writes that he “took the work seriously and put his heart into the mission,” while Kenneth Lynn, author of a 1995 Hemingway biography, suggests that the whole thing was more of “a lark.” Ambassador Braden was effusive in his praise at the time, claiming that Papa made a real contribution to the war effort. Captain Ramírez Delgado, the only Cuban to sink a German U-boat during World War II, was less enthusiastic, calling the writer “a playboy who hunted submarines as a whim.”

Personally, I’ve always admired Hemingway for his taut prose and gripping stories, while recognizing the hyperbole surrounding his larger-than-life personality. He might have been a celebrity, but he wasn’t a coward. The writer acted with valor in World War I, operated behind enemy lines in the Spanish Civil War, and would go on to report bravely from Normandy.

For me, Hemingway’s Cuba escapades were more of a hiccup. Naive? Yes. Desperate? Perhaps. But if his luck had gone another way, things might have turned out differently. Rather like that other rugged American scribe, Jack London, who had ventured confidently off to the Klondike 50 years earlier, Hemingway didn’t find any gold, but he uncovered plenty of raw material for his stories. ✯

WHEN YOU GO

U.S. citizens need to apply for a “general license” to travel to Cuba in one of 11 categories listed by the U.S. Treasury Department (use the search function and enter “Cuba”). Independent travelers with no specific affiliations are best off qualifying under the “support for the Cuban people” category.

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

U.S. citizens are currently only allowed to stay in private accommodations; the closest to Cayo Guillermo are in the mainland town of Morón. For non-U.S. citizens, one of the best hotels on Cayo Guillermo is Gran Muthu. Highly recommended in Havana are the privately run Hostal Peregrino and art deco-themed Casa 1932.

Fresh seafood is the star of several beach restaurants. Ranchón Flamenco in Cayo Coco serves lobster, shrimp, and red snapper.

WHAT ELSE TO SEE AND DO

The most famous Heming-way-got-drunk-here bars in Havana are El Floridita (Obispo No. 557) and La Bodeguita del Medio (Empedrado No. 207).

To see all the Hemingway sights, including his home, Finca Vigía, take a day trip through Havana Super Tour.

Fishing trips on Cayo Guillermo can be organized at any of the cay’s hotels. ✯

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.