Nine million square miles. That’s the size of the patrol zone assigned to American submarines in the Pacific Ocean during World War II. From Perth to the Kurile Islands. From the Gulf of Tonkin to Tarawa Atoll. It was an area encompassing coastal littorals, narrow passages, and open ocean. Within that vast region, a force of fewer than 230 subs managed to send to the bottom 55 percent of all Japanese ships sunk during the war: 1,200 merchantmen, 214 men-of-war, 5,600,000 tons in all—more than twice the vessels sunk by all other services combined. The subs helped starve Japan of inbound raw materials and slowed outbound replenishment of bases and garrisons across the empire. By any standard, the U.S. Navy’s undersea achievements in the Pacific were a resounding success.

On the other side of the world, in the more confined waters of the European Theater, it was a different story. American submarines played only a paltry role in the defeat of Germany—though not for want of trying on the part of their crewmen. The force never exceeded the six boats of the single unit operating there, Submarine Squadron 50, and spent only eight months on station patrolling off Western and Northern Europe. The results there were, by any standard, meager.

“Subron 50” got its mission based not so much on some grand strategy but on a personal request by British prime minister Winston Churchill of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Second Washington Conference in June 1942. At that point in the war, German U-boats were still taking a prodigious toll on Allied shipping. Churchill reasoned that intervention by American submarines, with their superior endurance and firepower, would help level the playing field in the North Atlantic by taking on the U-boats, freeing up the smaller British subs for service in the North Sea and Mediterranean. Roosevelt was game, but his commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, strongly disagreed with the proposal, arguing that every sub the United States could build should be sent to the Pacific to help alleviate a shortage of boats in that theater.

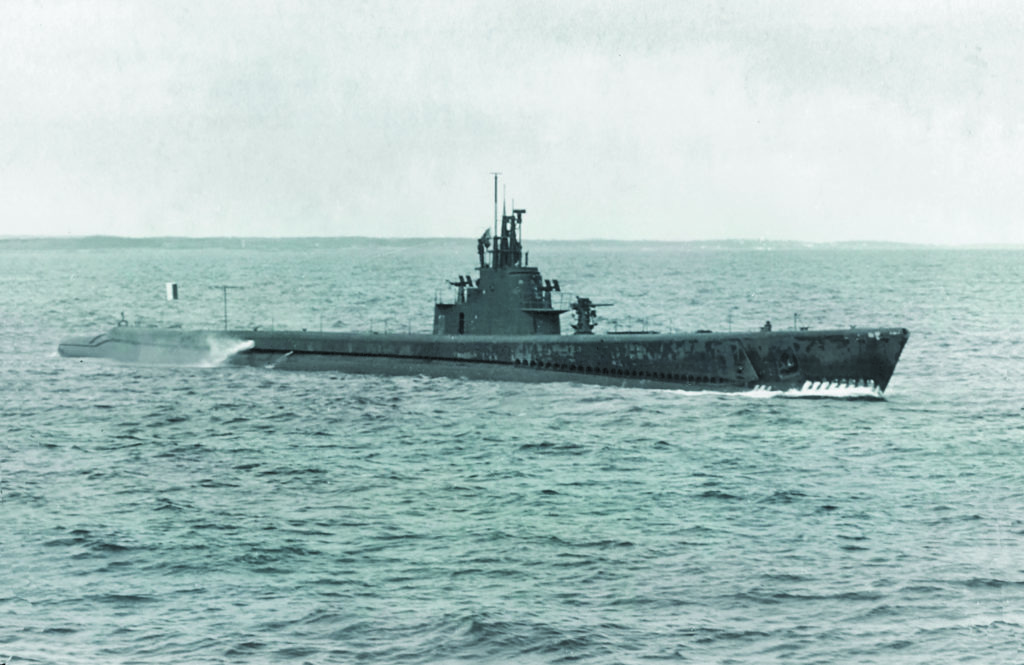

Not surprisingly, President Roosevelt prevailed. On September 3, 1942, Submarine Squadron 50 was established at New London, Connecticut, under the command of veteran submariner Captain Norman S. Ives, 45. American shipyards were only just gearing up for volume production of fleet-type submarines, so Ives had to cobble his unit together as best he could. He managed to source six Gato-class boats already earmarked for Pacific duty. Each was 312 feet long, carried 24 torpedoes, and had a top speed of 21 knots and a range of 11,000 nautical miles. An ancient sub tender, USS Beaver, would supply logistical support. On October 19, the first three—Blackfish, Gunnel, and Shad—set out on their Atlantic crossing. Herring and Barb followed the next day; troublesome engines kept Gurnard two weeks behind them. In the meantime, Beaver had gone ahead to set up housekeeping at U.S. Naval Base II, in Rosneath, Scotland, 24 miles northwest of Glasgow.

But before the subs even crossed the Atlantic, the squadron’s original assignment of fighting U-boats was temporarily scrubbed for a more immediate task: supporting the first large-scale amphibious landings in the European Theater. Dubbed Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa was scheduled to kick off on November 8. An eyewitness to it all was Barb’s Brooklyn-born engineering officer, Lieutenant Everett H. Steinmetz, then 29. Of medium height, slim build, and balding pate, “Steiny” was known for his wry sense of humor. Labeling Torch “an ambitious undertaking,” he noted that it “called for night landings by inexperienced troops launched from transports with insufficient training on a coast about which our forces had little intelligence.”

When the Barb departed New London, it carried five U.S. Army Rangers. The crew was puzzled by their presence until their skipper, Lieutenant Commander John R. Waterman, told them about the Allied invasion and the sub’s assignment to drop the GIs off in Morocco—then under Vichy French control—at a small port south of Casablanca. Along with three other subs in the unit, Barb also performed reconnaissance and patrol duties during the assault. It was a fraught enterprise. Amid the confusion of the landings, Gunnel—skippered by Lieutenant Commander John S. McCain Jr., father of late senator John S. McCain III—was strafed and bombed by an Allied plane. Fortunately, the damage was minor. (A fifth sub, Blackfish, had been deployed 1,600 miles south to Dakar, French West Africa, to interdict any Vichy warships sortieing to aid their Morocco-based sisters.)

On November 8 Herring bagged Subron 50’s first confirmed sinking. That morning Lieutenant Commander Ray Johnson was watching through the periscope as an unescorted freighter rounded Cape Mazagan, off Morocco’s northwest coast. Sailing southward, the ship—Ville du Havre, a 5,700-ton Vichy French vessel—hugged the coastline, trying to blend in with the hills beyond to avoid detection. At 10:03 a.m., the skipper called “Battle stations!” His crew responded smartly as he brought the submarine around to a new course, closing the distance to his target. Tensions were high in the sub; it was their first attack. At 10:52 Johnson fired a spread of two torpedoes, knocking a chunk off the freighter’s bow and stopping the vessel dead in the water. A third fish hit near the stern. The ship slowly settled and sank. His morning’s work done, Johnson steered his boat back to its patrol line off the coast of Casablanca.

WITH THEIR NORTH AFRICA TASKS COMPLETE, the squadron’s five boats set course north for Base II in Scotland, there to join the late-arriving Gurnard. Unfortunately, Gunnel’s bad luck persisted during the voyage, when all four of its German-designed diesel engines conked out. That left only a small auxiliary engine to charge the batteries that drove the sub’s motors. Chugging along at 3.5 knots, Gunnel finally showed up at Rosneath on December 7—10 days behind its mates.

Steiny was decidedly unimpressed with the base, bemoaning: “Rosneath was as dreary as the weather and offered nothing in the way of diversions.” About the only cheery place in the neighborhood was the sprawling Ferry Inn, built in the 1890s for Queen Victoria’s daughter Louise, and in 1942 commandeered by the U.S. Navy as a billet for officers. The limited choice of food at the base left something to be desired. The lieutenant rued the daily ration of Brussels sprouts, then bountifully in season: “They came aboard by the ton. I still wince when I see one,” he recalled 55 years later.

Gunnel was at Base II only briefly for temporary repairs before sailing back to New London for a complete overhaul. While Subron 50’s remaining boats were undergoing refit by Beaver’s maintenance crews in preparation for the next round of patrols, operational command of the unit passed to the British Admiralty. It was they, after all, who had requested the services of the American subs.

The mission to battle U-boats in the North Atlantic was once again put on the back burner. The squadron was given the challenge of stopping blockade runners transporting goods from neutral Spain to Vichy France in the Bay of Biscay. The bay, shaped like a backward “C,” is some 320 miles wide both east to west and north to south, splashing up on the shores of western France and northern Spain. The Admiralty believed Spanish coastal waters would be rich with juicy targets; the American subs were expected to attack cargo ships operating under French and German flags that were suspected of carrying war materiel.

On November 28, 1942, Gurnard, which had missed out on the North African fracas, was the first boat to transit down to the bay. But it soon suffered the same catastrophic engine failures as Gunnel and also returned to the States. Subron 50 was down to four ships.

“Our orders were simple,” Steiny later recalled. “Remain submerged during daylight, identify contacts, and attack if hostile. But respect neutral waters and avoid detection.” Respecting neutral waters proved a particularly difficult endeavor. Because Spain was neutral, Barb and the other subs could not conduct their raids inside the 12-mile limit recognized internationally as “territorial waters.” They were also expected to positively identify their quarry before boring in. These strict rules of engagement hampered operations and failed to prevent one costly mistake.

While cruising off the Spanish port of Vigo on December 26, 1942, Barb spotted a tanker the skipper believed to be German. Commander Waterman ordered a night surface attack, fired four torpedoes, saw two hit, then resumed his patrol. Steiny recalled that “spirits soared” among the crew. But when the sub returned to base in mid-January 1943, the Admiralty immediately called the skipper to London to defend his actions. They told him that his target had not been German, but the 6,700-ton SS Campomanes—a Spanish vessel. The Admiralty ordered Waterman to deny the incident ever happened. Steinmetz learned after the war that the Spaniards had protested vehemently to the British about the egregious breach of neutrality. The British naval attaché in Madrid smoothed things over by telling the Spanish Foreign Ministry—quite truthfully—that the attacking submarine was definitely not British. He suggested the Germans were to blame.

During the first three months of 1943, Subron 50’s submarines each made four patrols in the Bay of Biscay, with little to show for their efforts. Shad sank a barge carrying iron ore bound for the Germans. Blackfish encountered a pair of heavily armed German antisubmarine vessels; the skipper decided to attack both and sank one. But the other counterattacked, damaging Blackfish’s conning tower and main air intake. And Herring identified a German coastal U-boat cruising on the surface some 2,500 yards away. In a matter of seconds, Herring fired two torpedoes. The sound of a heavy explosion followed two minutes later, the victim’s screws stopped, and the soundman on Herring heard “loud crackling noises,” as if the target was breaking up. Alas, intercepts of encrypted German radio messages indicated to the British that no U-boat had been sunk at that place and time. It apparently had been a Spanish trawler.

This Atlantic patrol business was getting downright disappointing. The problem lay not with a dearth of juicy targets but the fact that nearly all were steaming under a neutral flag. Steiny noted that on Barb’s second patrol, the sub’s log recorded 485 fishing vessels and 127 large ships—all nonbelligerents.

IN APRIL 1943 the Admiralty overhauled its Subron 50 strategy by redeploying the American submarines to Norwegian waters 300 miles above the Arctic Circle to augment a British anti-U-boat patrol already on station. Barb and Blackfish were the first to sail. The pair was also to watch for the expected breakout of the German battleship Tirpitz, then anchored in Altafjord near the northern tip of Norway. Had one of the American subs successfully attacked the behemoth it would have been a stunning triumph. As usual, Lady Luck thumbed her nose at the squadron; Tirpitz never sortied from its hiding place deep in the fjords.

On April 28 a lookout on Barb spotted a periscope sticking out of the sea a few hundred feet off—a U-boat. “It was a miracle we didn’t collide,” Steinmetz recalled. “We dove and went to silent running.” He then chuckled when he added that the enemy sub was so close, “his periscope observation [of us] probably consisted of a lens full of black paint.”

But Barb’s commander was in no mood that afternoon to tangle in a fully undersea battle, a fraught enterprise for subs. Otherwise, sightings were few—far fewer than off Spain. As Steiny noted, “Why would anyone in their right mind be there anyway?” The only targets Barb had an opportunity to attack were dozens and dozens of floating mines. “Fired at them with the rifle, machine gun, submachine gun, and 20mm. The mines neither exploded nor sank,” skipper John Waterman reported. But “it helped relieve the monotony of the patrol.”

Two new subs, Hake and Haddo, joined Subron 50 at the end of April 1943, replacing the departed Gurnard and Gunnel, but there was little for them to do. In late spring the Admiralty and the Americans both concluded that the U.S. submarines were only getting in the way of the Allies’ increasingly successful campaign against the U-boats, which was using a combination of new technologies and time-tested tactics. In June 1943 Admiral Harold Stark, chief of United States Naval Forces, Europe, ordered Subron 50’s six boats transferred to the happier hunting grounds on the other side of the world.

“Having taken care of the Atlantic,” Steinmetz wryly recalled, “we were now ready for the challenges of the Pacific.”

IN THAT THEATER the former constituents of Submarine Squadron 50 shined. Barb sank 17 Japanese ships, ending its war in fourth place for most tonnage sunk by a single sub. Gurnard and Gunnel sank a total of 18 ships; replacements Hake and Haddo racked up the same score, and Herring got seven. But the enemy got Herring: the boat was lost to gunfire off northern Japan’s Kurile Islands on June 1, 1944.

The American submariners’ successes in the Pacific can be chalked up to operating within a command environment that diligently learned from its mistakes and continually updated its doctrine and tactics. Subron 50’s time in Europe, on the other hand, yielded few lessons learned. And the tangible tally stemming from Churchill’s 1942 request was negligible at best. Throughout 27 patrols, the confirmed results for Subron 50 were two ships sunk, four damaged.

Nevertheless, there were important intangible benefits of an endeavor the British considered a modest success. “Your submarines’ actual contribution had been very great, far beyond the numbers of ships sunk,” the Royal Navy’s commander of subs, Rear Admiral Claud B. Barry, wrote to squadron commander Ives. While Barry didn’t elaborate, the presence of Subron 50 helped relieve Britain’s beleaguered submarine service. And it provided a show of American support for Britain in its time of need—support that made the “special relationship” long shared by the two allies even stronger. ✯

This story was originally published in the October 2019 issue of World War II magazine.