Bad roads and mountains made ditches and locks the most modern mode of transportation—for a while

UNDER THE 1783 TREATY OF PARIS, Britain relinquished to the United States of America claim to all land in North America east of the Mississippi River and roughly south of the 49th parallel. That cession made the upstart country one of the world’s largest. For Britain, America had embodied such seemingly endless opportunity that in colonial charters English monarchs granted recipients parcels extending “from sea to sea.” This appetite for land colored the former colonials’ outlook just as, during two-plus centuries of European rule, they had absorbed and modified so many continental institutions and customs to fit their expansive setting.

Consider transportation. In England, conveyance of goods and passengers was often a money-making proposition. Creating roads on so small an island, long inhabited and densely populated, required getting easements and rights of way from property owners, as well as permission from Parliament. Road builders made money charging tolls, a model adapted to waterways in the 1700s, when investors moved from building roads to building canals. Thanks to nascent industrialization, canals, previously unprofitable risks, almost overnight became practical necessities. These conduits—relatively short, narrow, shallow, and plied by capacious boats built for shallow-draft commerce—evolved into a network linking industrial centers in the Midlands to mining districts in the southwest. To tow canal boats, crews worked teams of animals trudging paths alongside waterways. Aqueducts carried canals over rivers and sometimes entire valleys, but British canal builders faced few natural obstacles. A scant change in elevation made it relatively easy to connect the Midlands to the southwest and London. Vertiginous Wales and Scotland got fewer canals.

Britons’ proprietary approach to canal building underwent an early trial in the New World, where roads were so bad that to get from the Northeast to the Southeast merchandise and passengers went by sea. Rivers navigable at their mouths soon became impassable upstream through a quirk of geology. Hardly a river flowing into the Atlantic did not collide with the fall line, the transition, marked by waterfalls, between the ancient hard rock of the Appalachian Mountains and the young sediment of the coastal plain. At those white-water zones, goods came off the boats to travel by wagon and even teams of porters who rolled, trudged, and eventually climbed over peaks higher than any in Britain using horses, donkeys, and shoe leather.

The alternative to portage, ambitious but expensive, was the canal. Mimicking the British model, investors including George Washington bankrolled the Dismal Swamp Canal. Built in the 1790s and early 1800s, this project connected the Chesapeake Bay via Julian Creek, near Hampton Roads, Virginia, to the Pasquotank River in North Carolina north of Elizabeth City on Albemarle Sound. Completed in 1805, the 22-mile canal, described as “a ditch filled with muddy water,” was making money by 1810.

Adjoining the canal and straddling the North Carolina/Virginia border stood the Lake Drummond Hotel, run by the canal company. The state line bisected the hotel’s interior; should a Virginia marshal arrive to bust a game of chance, players scuttled to the North Carolina side and kept dealing, and vice versa.

Over the next 15 years, profits from the canal and the hotel funded expansion of the ditch into a 40-foot channel eight feet deep, with five locks. Locks, or pound locks, enable lock keepers to float canal boats up or down a steep passage. The Chinese built the first pound locks in 984, but in the West these mechanisms were unknown until 1396, when Belgian engineers independently invented them. The technique involves controlling the water flow in and out of a series of canal compartments. A pound lock has watertight gates, one upstream, the other down, enclosing enough canal to float a boat or more. Each gate has sluices to let water in or out. At least one gate is always closed. Upon admitting a boat, the other gate closes, impounding water. If the boat needs to ascend, the sluice allows water into the compartment to raise the vessel. If the boat needs to descend, the sluice is opened to drain water, lowering the craft.

Other canal projects sought to open the American interior, but private money generally evaded such undertakings. The British model, which worked so well on that small, densely populated island, was a non-starter in vast, unsettled North America. Investors had to absorb years of construction expenses before seeing a return, and profitability was chancy. Boosters dreamed of canal-connected cities thriving along the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, but reality was deflating. When Ohio joined the Union in 1803, Cincinnati counted about 2,500 residents; the hamlet that became Cleveland had 10.

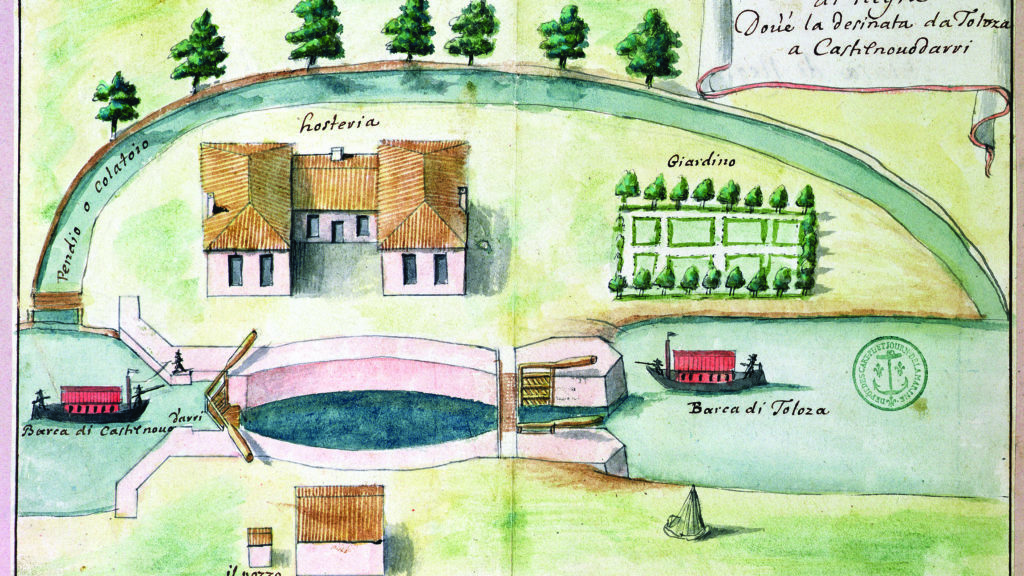

The French had pioneered a solution that would work in America. The Garonne River starts near the Mediterranean, north of the Pyrenees, and flows northwest to the Atlantic at Bordeaux. The dream of connecting the Garonne at Toulouse via a 150-mile canal with a Mediterranean lagoon called the Etang de thau, avoiding an 1,800-mile-plus sail around the Iberian Peninsula, was not new in 1661, the year King Louis XIV authorized such a project. Augustus Caesar, Nero, and Charlemagne all had envisioned a canal between the Garonne and the Mediterranean, but none figured out how to get boats over a summit between them. The lock’s arrival made that possible—at a cost so high only a government could fully fund it. To build the Canal du Midi, its wealthy designer, engineer Pierre-Paul Riquet, personally advanced 20 percent of the expense. The French crown and the regional government of southern France covered the other 80 percent. The 14-year project, completed in 1682 at a cost of about 17.5 million livres, or around £1.3 million, sped goods between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic on a route safe from pirates and less vulnerable to bad weather. The Canal du Midi, with its 63 locks, was the Western world’s longest artificial waterway—until 1825, when the Erie Canal, emulating the French model of private/public financing, came along.

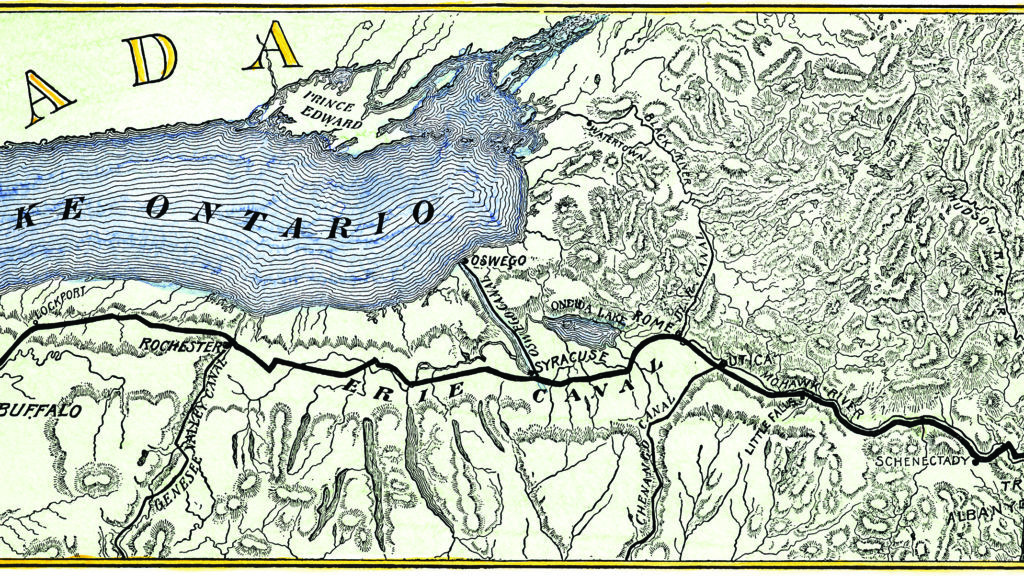

As early as 1724, boosters in what is now upstate New Yorkwere floating the idea of a canal linking Lake Erie to the Atlantic using the only eastern river that could allow ocean-going vessels past the fall line. Between Peekskill and Cornwall-on-Hudson, where the Appalachian Mountains descend to their lowest, the Hudson River zigs and zags through the fall line—a narrow and tricky route, but not impassable. However, the geology of New York’s western tier did pose daunting barriers. To carry shipborne commerce between Lake Erie and the Hudson required a 360-mile canal linking Buffalo and Albany. The river town stood nearly 600 feet lower than the lake port—a forbidding elevation change demanding 50-plus locks and more labor than seemed feasible.

The first concrete endeavor to open a water route across upstate New York came in 1792, when Gouverneur Morris, Philip Schuyler, and Elkanah Watson chartered the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company. Their modest goal was to make the Mohawk River, a Hudson tributary that rises tantalizingly close to Lake Ontario, entirely navigable. Using private capital, they proposed to build lengths of canal bypassing rapids and other obstacles on the Mohawk using locks.

When construction began, upstate flour merchant Jesse Hawley saw an opportunity to profit. Hawley prepared to ship flour milled near Seneca Falls, on the Mohawk, for sale in New York City, 270 miles south, and other coastal locations. The Morris plan did not pan out—the canalized Mohawk never reached Seneca Falls—and Hawley lost his shirt. He spent nearly two years in debtor’s prison. In stir, under the pseudonym “Hercules,” Hawley wrote editorials calling for a canal connecting Lake Erie and the Hudson. His essays are remarkable in their detail and their predictions. A canal linking Lake Erie to the Hudson would be such a boon to the city of New York, he wrote, that “in a century its island would be covered with the buildings and population of its city.”

As Hawley was proselytizing, the federal government was amassing budget surpluses that President Thomas Jefferson said should go for infrastructure. Backers thought the Erie Canal embodied Jefferson’s notion. However, in 1809, as a lame duck after James Madison’s election, Jefferson tarred the canal as “nothing short of madness.” If a canal was to be built to Lake Erie, it would have to be built with private funds, or by the state of New York.

In 1810, Thomas Eddy and Jonas Platt took up the cause. Eddy was a director of the Morris/Schuyler outfit trying to canalize the Mohawk. Platt was a state senator who saw that the canal would have to be a state project and that success lay in shooting for the moon—half-measures like the Mohawk River would not open the door for trade with the west. Together the partners pitched a largely artificial waterway from Buffalo to Albany and sold DeWitt Clinton on it. Clinton, nephew of nine-time New York governor George Clinton, was a seasoned politician—variously mayor of New York City, New York’s governor and lieutenant governor, and U.S. senator representing the Empire State. The canny Clinton, convinced a canal was feasible, went all in behind the notion.

In the boom years uncorked by the conclusion of the War of 1812, even hardened skeptics like Martin Van Buren, a longtime adversary of DeWitt Clinton, had to admit that an Erie Canal was achievable. After much legislative wrangling, including another failed attempt to get Washington to back the project, by 1817 all was set to go.

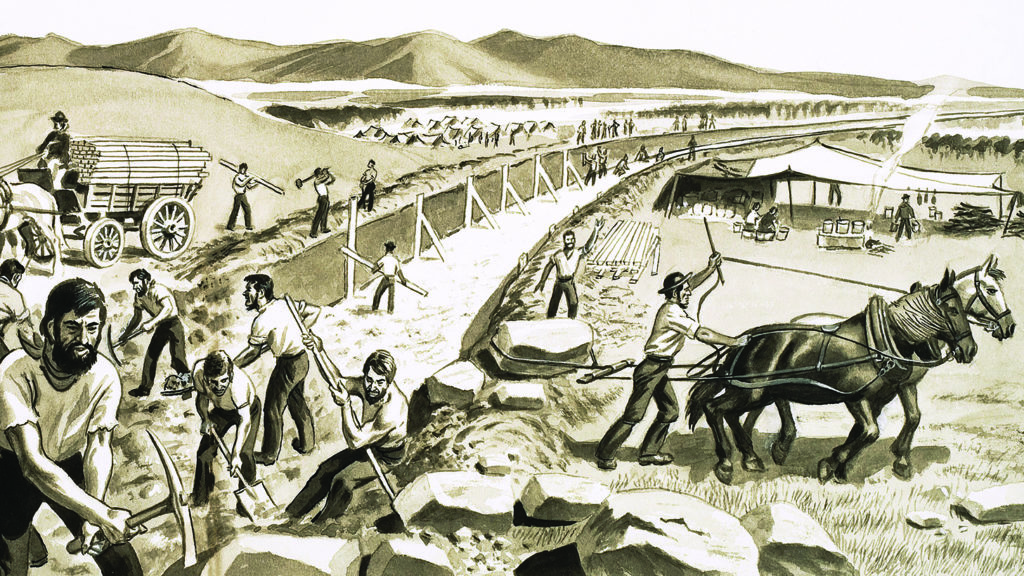

Now the obstacles became geographical. From Albany to Schenectady the proposed canal ran parallel to the Mohawk River until it reached a narrow gorge, where a pair of aqueducts had to be built to get the canal through. The waterway would follow the Mohawk to Rome and cut across to Oneida Lake. To depart the lake the route would take the Seneca River for a brief stretch before traversing western New York’s wilderness. Local crews did much of the digging, which first required clearing a swath 60 feet wide through forests thick with deadfall and understory. Improvised devices helped fell trunks and pull stumps. Men drove horse teams pulling oversize plows to cut overland portions of the canal bed. Discovery of raw materials for cement near Syracuse sped the task. Approaching Rochester, the route crossed a mile-wide valley. Cut by Irondequoit Creek, which in this vicinity was more of a river, the valley was 70 feet deep, its sides too steep for locks and the valley floor too unstable—in spots there was quicksand— to support an aqueduct.

The solution triggered the first great Irish influx to America. The Irondequoit Valley project’s complexity and scale demanded imported expertise and labor. The canal commission awarded the bid to J.J. McShane, a canal builder from Tipperary, Ireland. McShane brought over some 3,000 Irish laborers and set them to building a stone culvert 100’ long, 25’ high, and 30’ wide. The channel, above the Irondequoit Creek, would be the canal’s path, with the valley filled in to support it. To stabilize the result, crews had to sink nearly 1,000 pilings and cover them with timber before they could empty the first load of fill. Despite these challenges, the Irondequoit stretch was completed in a summer. By fall 1822, the Erie Canal was crossing the valley on an embankment 50 to 60 feet above the Irondequoit.

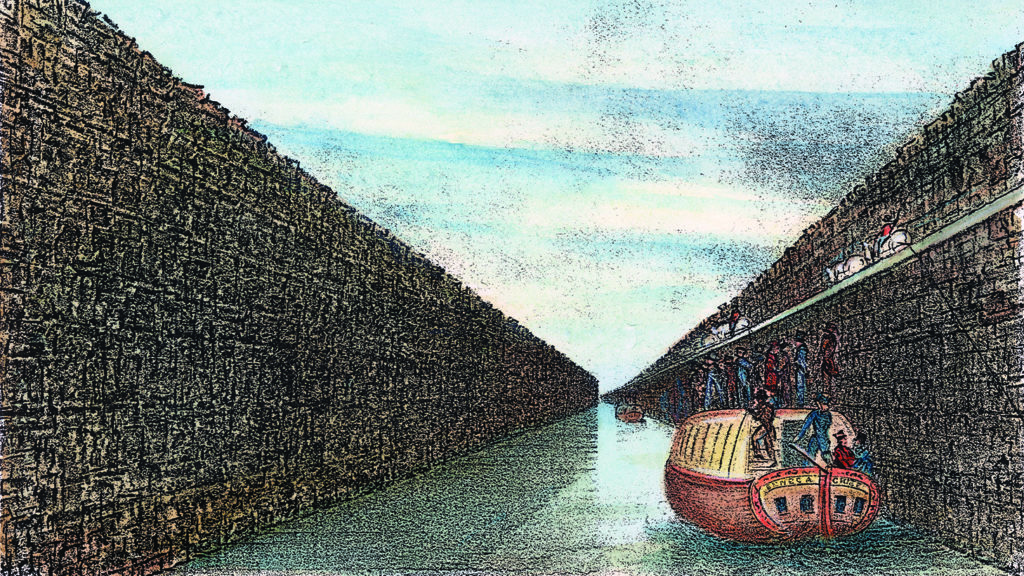

The final obstacle was the Niagara Escarpment, a thick layer of prehistoric seabed forming a line of limestone cliffs across all of western New York, and parts of Ontario and Pennsylvania. At the most favorable location for the canal to vault the cliffs, the escarpment still stood 70 feet above adjacent terrain. Self-taught engineer Nathan Roberts designed two sets of five locks each that would ascend 60 feet of escarpment in 12-foot lifts cut into the limestone. To surmount the remaining ten feet of escarpment Irishmen cut a seven-mile channel by hand. The town that grew and spread alongside the worksite came to be called Lockport.

Good management, labor-saving inventions, luck, and Irish greenhorns ready to sweat got the Erie Canal done on time and about as close to on-budget as possible. The canal, 360 miles long, four feet deep, 40 feet across, and punctuated by 83 locks, opened in 1825, eight years after construction commenced. The enterprise ran up a total cost of about $7.1 million—only about 5 percent over initial estimates.

The impact on trade was immediate and significant. The cost of shipping goods from the interior to the coast fell 90 percent, and in the first full year of operation toll revenues exceeded the construction cost. Passenger travel vastly exceeded expectations—more than 40,000 paying customers in 1825 alone. The canal became a leg on the Underground Railroad. Runaway slaves stowed away on canal boats bound for Buffalo, a short jaunt to Canada and freedom.

A culture and a way of life sprang up around the canal, especially among the loose-knit fraternity responsible for moving freight from the inland sea at Buffalo to Albany and back again.

Canallers—‘canawlers’ as they said—developed their own argot, pecking order, and legends. It was easy to find a job on the canal. Entry-level positions were everywhere. A youngster taken on as a “hoggee” would be thrown untrained into a shift of controlling the mule team. Because mules worked an assigned portion of the towpath, a hoggee didn’t walk the full length of the canal but stuck with his team, trudging the same 15 miles day after day. Most young men who tried being hoggees soon tired of watching the back end of the same mules along the same 15 miles of canal that their teams trod day in and day out. The main idea was to avoid falling in. Working on canals between Cleveland and Pittsburgh, young Ohioan James Garfield dunked himself 16 times in six weeks, sickening him and sending him home. Garfield’s towpath stint propelled him through school and into the law, service in Congress and the Civil War, and Congress again before winning the White House in 1880.

Hoggees who toughed it out stood to move up to boatman, traveling the length of the canal, and at voyage’s end, when they were paid, cutting loose in whatever town they landed in—the rollicking song “Buffalo Gals” suggests the delights available at the canal’s western terminus.

Life on the canal was soon romanticized—and exaggerated. One legend, that of the Empeyville Frog, brought notoriety to a crossroads about 12 miles north of the Erie Canal. Supposedly a giant frog named Joshua, weighing a ton, specialized in straightening roads. The story went that locals chained the oversize croaker to meandering thoroughfares and goaded Joshua into jumping, which pulled out the kinks. Canal lore held that, like Joshua, everything was bigger in the big ditches, including fish, a claim illustrated by the story of a blacksmith who made a crowbar into a hook, tied the result to a towrope, hung a piglet as bait, and cast off from a canal boat loaded with barley. A humongous Lake Erie sturgeon bit, hauling the boat and its mule team backwards for miles until the fisherman looped the towrope around an abutment, with the hoggee barely keeping his animals out of the drink. “For weeks after that,” a canaller swore, “we had to harness those mules with their heads facing the boat, they were so used to going backwards.”

anal legends came closest to reality in characterizing fights among the fellows who manned the boats and tromped the paths. Along routes beyond the reach of anything resembling law enforcement, it made business sense to salt a crew with skilled fighters, because when two boats arrived simultaneously at a lock, the accepted process for deciding which went in first seems to have been a fight between each side’s champion, loosely refereed by the lockkeeper.

Lockkeepers had small residences at locks and were expected to work around the clock. To augment their monthly salaries some locksmen operated general stores—perhaps the first 24-hour convenience marts—and saloons, always sure of a steady stream of customers. The keeper had a temporary captive market for his wares and refreshments while the water level was raised or lowered in the lock.

The Erie Canal had a four-mile-an-hour speed limit, but horse and mule teams on the towpath could do little more than five mph. Passengers could travel from Albany to Buffalo in five days; most freight shipments took six. Passengers ordering meals en route paid about four and a half cents a mile; skinflints could save a penny a mile bringing their own grub. The 152-mile trip from Utica to Rochester cost $6.25, roughly a week’s pay for a clerk.

The Erie Canal’s success spurred an outbreak of canal fever.Pennsylvania, with its far more challenging terrain, embarked in 1824 on a series of projects that included canals and a railroad between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. By 1840, Pennsylvania had more than 1,200 miles of canals, the longest—the Main Line—ran 391 miles between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, and at the east end incorporated 82 miles of rails. The Keystone State’s canal network mainly improved intrastate transport. Although offering connections to the busy Ohio River, the Pennsylvania canal system was no match for the Erie Canal as a conduit for westbound goods and travelers.

Between 1827 and 1832 Ohio legislators funded and built slightly more than 300 miles of canals connecting the Great Lakes to the Ohio River. Promoters in Maryland pitched a privately funded canal linking the Potomac River at Washington, DC, to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal eventually required significant funding from the state of Maryland and the federal government, and never crossed the Appalachians, as originally intended. Though significantly shorter than the Pennsylvania, Erie, and Ohio canal systems, the C&O transited far more difficult terrain. The Erie Canal had cost $7.1 million; to build the C&O from Washington to Pittsburgh, a run of 341 miles, was estimated at $22 million. The 185 miles that were completed between Washington and Cumberland, Maryland, cost $11 million—per mile the most expensive major canal project 1800-50, and the only one that fell short of its intended goal.

Besides major canal projects, a host of smaller canals spread from New Hampshire to Georgia. Ill-advised, poorly surveyed, and pitched with unrealistic expectations of cost and future traffic, these undertakings rapidly exhausted their private capital and began tapping state budgets. States sold bonds to fund canals, fueling a bubble that burst in 1837. In the ensuing recession several states defaulted on bonds.

The Panic of ’37 did not end the American canal’s brief golden age—the steam engine did. Calamity was baked into progress. On July 4, 1828, the C&O Canal staged an official groundbreaking near Georgetown, the Maryland port adjoining the capital and the eastern terminus of the canal. The same day in Baltimore, 40 miles north, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad broke ground. By the mid-1830s, steam-powered locomotives able to operate year-round, in contrast to frozen canals, were pulling trains of freight cars faster and more heavily loaded than canal boats. Canals that did not freeze over competed favorably with trains for a decade before rail rates undercut those for canals. During this interregnum, the canal was king. Towns grew rapidly along the watery thoroughfares and with them a way of life and a pattern of settlement that would repeat on a grand scale when transcontinental railroads arrived in 1869.

In 1825, the year the Erie Canal was completed, the village, now home to 600, incorporated as Syracuse, New York, and was nameless no more. In 1828, the Oswego Canal, linking the Erie Canal to Lake Ontario, passed Syracuse, and by the 1830 census 11,000 people lived there. A similar narrative unspooled west at Rochester, which also provided a connection between the Erie and Lake Ontario and benefited from the rapids on the Genesee River, whose speed and volume drove multiple mills. The Erie Canal funneled much Midwestern grain to New York—and all along the route, thanks to those rapids, Rochester was best situated to mill that grain. By 1838, the town was known as “Flour City.”

Canals enjoyed a brief American heyday. By 1900 every major canal but the Erie was in disarray. Some waterways were being used for local haulage; others were backfilled and repurposed as railbeds or roadways. Even the Erie, designed to carry 1.5 million tons of freight yearly, eventually staggered, and largely was replaced in 1918 by the New York State Barge Canal. Where canals do survive, their traffic has been largely reduced to recreation and tourism. Even with a boom in shipments since 2010, the entire New York state canal system—which includes both the Barge Canal and the Erie Canal, as well as numerous feeder lines, saw only about 200,000 tons of freight traffic in 2017.

_____

Towpath Tune

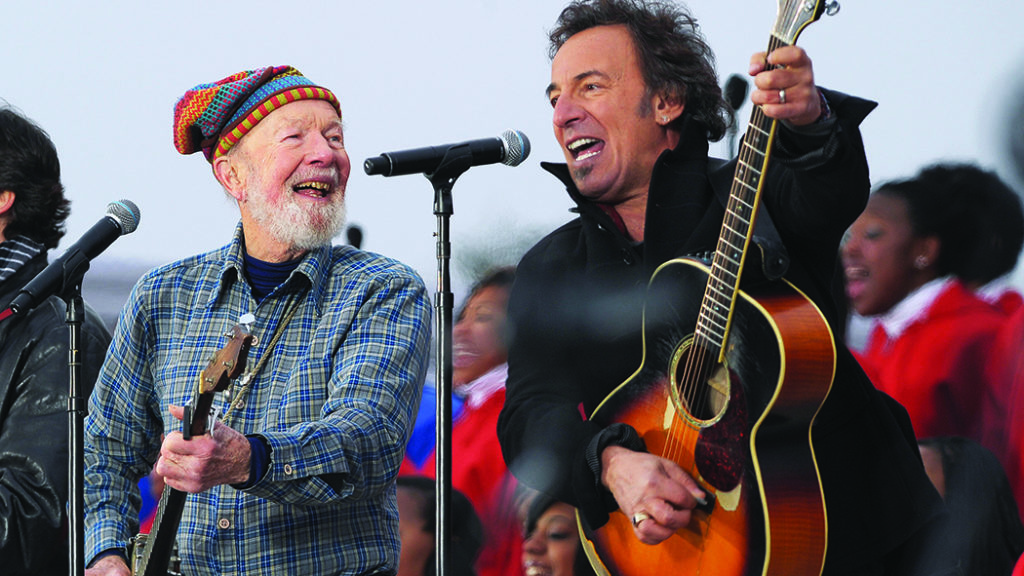

Ask an American to sing a song about a canal and chances are good the response will start with “Low bridge, everybody down!”—the open to the refrain of “Erie Canal,” a campfire anthem that conjures images of barge crews and mule teams. Bruce Springsteen’s embrace of the tune has rekindled debate as to whether “Erie Canal” is folk music or a folky commercial song.

Liner notes to Springsteen’s 2006 LP We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, describe “Erie Canal” as “written in 1905 by Thomas S. Allen as ‘Low Bridge, Everybody Down,’ but now it’s as much a folk song as if it had been written eighty years earlier in the canal’s heyday.” The fact that Allen, a Natick, Massachusetts, vaudevillian, published “Erie Canal” in 1913 is central to the argument that the song came from Tin Pan Alley, not canallers working the big ditch—except that in 1930 a court decided the tune predated Allen’s copyright.

As the LP subtitle indicates, the Boss borrowed his version from folk singer Pete Seeger. A fixture in progressive political entertainment since the 1940s, Seeger presented his 1961 take as the traditional number mid-century revivalists believed “Erie Canal” to be. From Bill Bonyun’s 1950 Smithsonian Folkways LP Who Built America to a 1963 arrangement by the Kingston Trio on the album #16, folk revival recordings ignored Allen not out of malign intent but because these musicians were working from songbooks, many of which failed to list Allen, who died in 1919, as the song’s ostensible composer. “It was not uncommon for the person who first transcribed a song to claim authorship,” writes folklorist Stephanie Hall. “Folk songs and minstrel show songs were often in oral circulation long before they appeared in published form.”

The ’50s folk revival owed much to efforts in the early 20th century to preserve and circulate genuine American folk songs. John Lomax collected an invaluable hoard of songs from across the country; he and later his son Alan produced multiple volumes that codified and popularized American folk music. From his childhood in the 1890s, Louisville, Kentucky-born John Jacob Niles studied the folk songs of the Appalachian Mountains. Philadelphia musicologist Sigmund Spaeth was well known for tracing popular songs’ folkloric roots.

In Read ’Em and Weep, his 1925 book of “songs you forgot to remember,” Spaeth wrote of “Erie Canal,” “This seems to be a real folk song.” Spaeth had acquired the song from George S. Chappell, a Connecticut architect and raconteur who also was Carl Sandburg’s informant for a version Sandburg published in his 1927 book American Songbag, which ranked the tune among those of “vulgar birth.”

Berkeley, California, folklorist R.W. Gordon had doubts about Spaeth’s and Sandburg’s claims for “Erie Canal.” Receiving the “Erie Canal” lyric by letter in the mid-’20s, Gordon wrote privately that “certain things about it make me fairly certain that it originated on the vaudeville stage rather than on the canal, and that it is not very old.”

Gordon was not alone. In 1928, Allen’s publisher, F.B. Haviland, sued Doubleday, Page, & Co., publisher of Spaeth’s book, alleging copyright infringement and seeking $25,000 in damages. At trial in 1930 in New York City, Doubleday’s lawyers had two expert witnesses sing the song for the jury and discuss their experiences with it. Erie County, New York, State Surrogate Judge Louis B. Hart, a prolific song collector, said he had learned “Erie Canal” in 1906. John Jacob Niles, by now regarded as “Dean of American Balladeers,” said he had learned the song in 1900. The trial also pointed out a discrepancy between the plaintiff’s version and that published by the defendants. Thomas Allen’s lyric reads “Fifteen years on the Erie Canal; ” Spaeth’s, “fifteen miles.” The variation sets apart versions that claim Allen as a source versus the alleged traditional versions. Jurors rejected Haviland’s infringement claim. “I believe that the song was a folk song in the public domain before plaintiff’s copyright,” Judge F.J. Coleman wrote in his summation. “Allen, who sold it to the plaintiff, is dead and we have no evidence of his authorship…Two witnesses testified to having heard the song many years prior to the date of the copyright and it is impossible to doubt their sincerity.”

Haviland had to pay the defense’s legal fees and the singing witnesses’ travel costs. Alan Lomax’s 1933 American Ballads and Folk Songs includes both Allen’s published version and one similar to Chappell’s that Lomax collected from Reverend Charles A. Richmond. The lyrics disagree, parting ways on Allen’s “fifteen miles” and Richmond’s “fifteen years.” Nonetheless, in 1939, New York folklorist Harold Thompson stated in his exhaustive survey of that state’s folklore, Body, Boots, & Britches, that he never had heard a canal worker sing “Erie Canal,” instead flatly attributing the song to Thomas Allen. Thompson’s endorsement may reflect the fade from the collective memory of the 1930 court decision rejecting Allen’s claim to authorship, perhaps presaging the acceptance of Allen’s dubious authorship reflected in the Seeger Sessions liner notes and countless other publications. —Musician and journalist Tyler Bagwell is writing a folk-music history of Buffalo, New York, from which he adapted this article.

_____

Canal Continuity

From the start, travelers took to America’s canals for business and pleasure. By day, passengers could lounge inside a reasonably capacious cabin stocked with seating and reading material or climb topside to enjoy the scenery—always alert to a cry of “Low bridge!” which demanded a quick leap to a lower spot to avoid a collision with a bridge built just high enough to let a canal boat pass.

Travelers did not complain about meals aboard, but they did gripe about the sleeping arrangements. Daytime congeniality evaporated when stewards unfolded Murphy-style bunks from cabin walls, leaving little navigating room. New York City Mayor Philip Hone described fellow passengers “packed on narrow shelves fastened to the sides of the boat like dead pigs in a Cincinnati pork warehouse.” Of a night on a canal boat, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, “Forgetting that my berth was hardly so wide as a coffin, I turned suddenly over, and fell like an avalanche on the floor, to the disturbance of the whole community of sleepers.”

Railroads and highways made canals impractical but often left their beauty intact. The longest canals have always had recreational users—initially swells on sight-seeing excursions—but now canal recreational traffic dwarfs commercial traffic. Towpaths are now bicycle and pedestrian trails serving cities that grew along the waterways. Passenger vessels are back, albeit way snazzier than their ancestors. Some luxe canal cruises go 16 days.

A landmark moment in this shift occurred in 1954, when Associate U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a noted outdoorsman and conservation advocate, began to fight a plan to make the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal into a federal highway. In a letter to The Washington Post Douglas challenged the paper’s editors to a hike. “Take time off and come with me,” he said. “We would go with packs on our backs and walk the 185 miles to Cumberland.”

The editors accepted. Joined by dozens of other interested individuals, the expedition set out on March 20, 1954, as a party of 58. Only nine hikers—including Douglas—completed the trek, but the publicity torpedoed the highway scheme. Since 1971, the canal has been a national park.

—Richard Jensen