The colonel headed a clandestine operations program that required brute force, innovation, and a strange-looking semi-submersible.

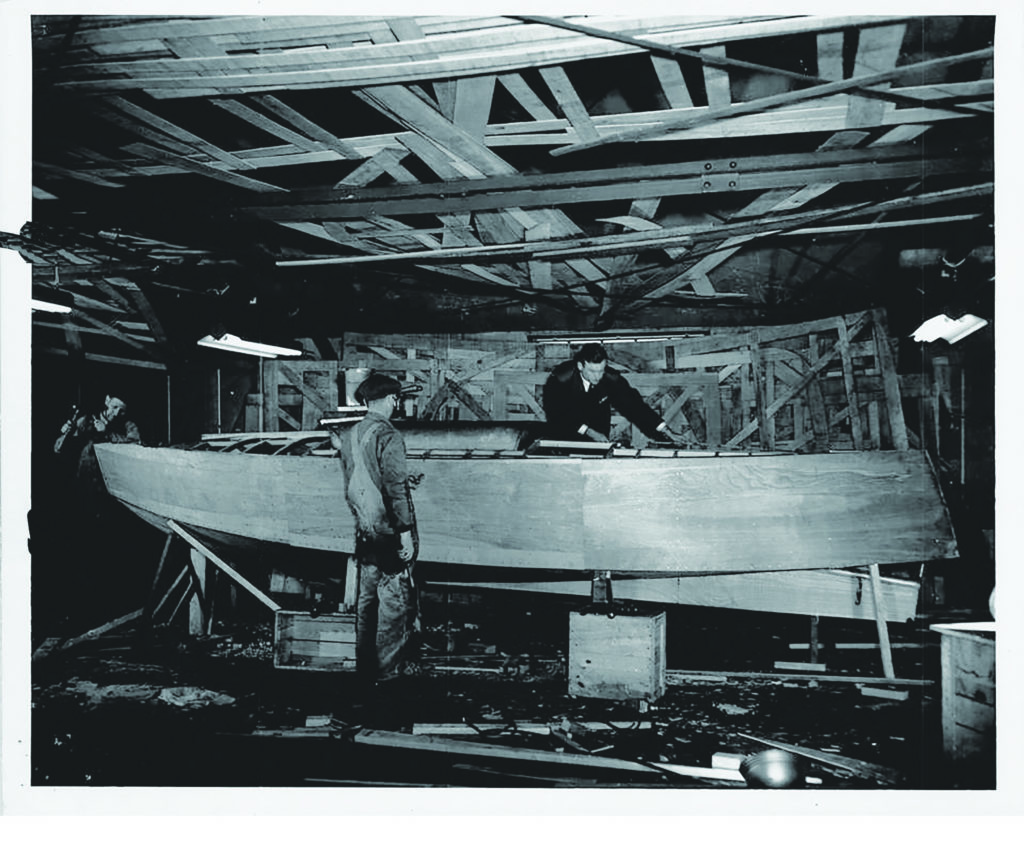

PERHAPS THE MOST PECULIAR CRAFT ever to ease its way into the Port of Los Angeles was “Gimik.” The 19-foot-long, 3,650-pound vessel looked like a design failure—something that had started as a closed lifeboat before the designer lost his mind. Gimik (a code name) had odd pipes sticking out of its foredeck and aft of a small plexiglass cube just big enough for one man’s head and shoulders. Made of plywood to reduce its signature on radar, it could run half-submerged, decks awash with little more than a foot of its “superstructure”—the cubular cockpit—showing above water. Gimik made little noise and created almost no wake; its 16-horsepower inboard gasoline engine could push it along at a top speed of about 4.5 knots.

Now, on a warm night during the fourth year of America’s great Pacific War, water lapped gently along the craft’s hull as it chugged through L.A.’s expansive harbor. No one—not a lookout on one of the many ships alongside the quays, or a mobile patrol boat, or even one of the so-called “tattletale” buoys designed to detect an intruder—reported Gimik on its test run. This victory led its patron, an army officer named Carl F. Eifler, to assert that the vessel was ready for its mission: to secretly transport men and equipment to enemy shores and wreak havoc on the Japanese Empire.

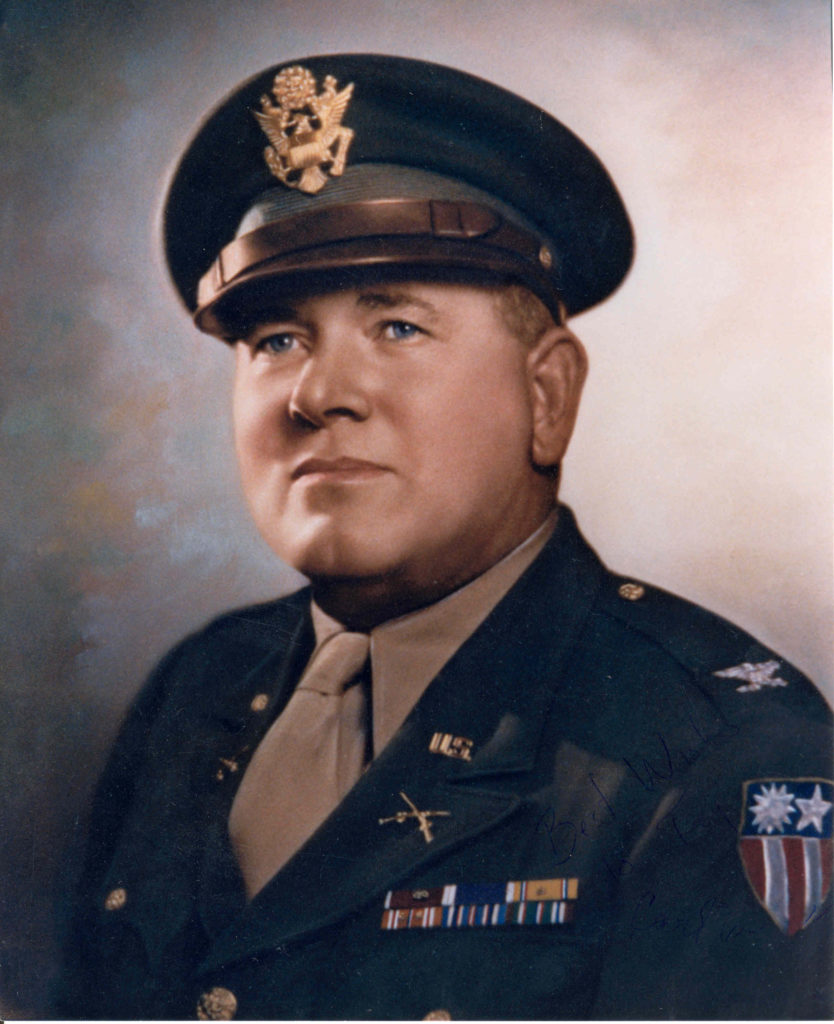

CARL EIFLER WAS one of the most colorful and charismatic members of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—America’s first central intelligence agency—created in 1942 to meet wartime needs. Even in an organization that had more than its share of swashbuckling originals, Eifler stood out.

He is typically remembered as the first commanding officer of OSS Detachment 101 (Det 101) in the China/Burma/India (CBI) Theater, where British, American, and Chinese forces fought the Imperial Japanese Army. But Eifler also played a leading role in two other high-risk, behind-enemy-lines operations that planners believed could affect the war’s outcome. The first, an initiative to kidnap a prominent German atomic scientist in 1944, did not bear fruit. The second, Project Napko, was an ambitious plan to set up agent networks in occupied Korea in 1945. Long-secret information regarding the Korea project has surfaced from vaults over the last few years, but historians have yet to piece together the whole story. Was it the product of Eifler’s fevered mind, a desperate move against an implacable enemy, or a calculated risk worth taking?

A good way to understand Napko is as a follow-on to Eifler’s work in Japanese-occupied Burma, where his mission was to harass invaders, collect intelligence, and rescue downed Allied pilots. The future OSS director, then-Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, created what would become Det 101 on April 22, 1942, for service under the senior American officer in the CBI Theater, Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell. Stilwell was officially chief of staff to the Chinese Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, but the two repeatedly clashed and Stilwell often wound up taking action on his own. Known behind his back as “Vinegar Joe” for his demanding nature and unforgiving words, Stilwell was willing to consider adding a largely independent military unit to his rolls—so long as it was commanded by an officer of his choosing, like then-Captain Eifler, a U.S. Army reservist on active duty in Hawaii.

The plainspoken Stilwell and Eifler were kindred spirits, having trained together in California in the 1930s. There, Stilwell had noted Eifler’s toughness and professionalism—perhaps even his finger-crushing handshake. Having received the nod from Stilwell, Donovan’s office drafted a set of mysterious orders directing Eifler to proceed to Washington.

After a very general orientation and some training in irregular warfare, Eifler headed for India to report to Stilwell, who seemed surprised to find the captain at his doorstep. According to one account, the general thought that his talks with the OSS had been preliminary, even theoretical. Still, he was willing to let Eifler run his own private war so long as he stayed out of the way. Stilwell said he did not want to hear from Eifler again until he had made his first “boom”—the sound of sabotage.

Though few in number, the men in Eifler’s unit leveraged the advantages that the dense jungle and its anti-Japanese Kachin tribesmen offered. By early 1943, Detachment 101 was on its way to organizing thousands of Kachin to fight a modern enemy from hidden bases. It would be rough, primitive work—far from a gentleman’s war. Eifler biographer Tom Moon would refer to it as “this grim and savage game;” at the same time, it was, in the words of Ronald Spector’s landmark history Eagle Against the Sun, “the beginning of one of the most successful guerrilla operations of the war.” Stilwell was pleased, and so was the OSS. Without question, Eifler’s star was rising, and he quickly vaulted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

EIFLER’S LUCK CHANGED on the night of March 7-8, 1943. Never one to hang back, the occasionally overweight yet always-strong 37-year-old—who stood about six foot two and weighed in at around 250 pounds—used his brawn to save a guerrilla operation from disaster on a stretch of Japanese-held coastline near Sandoway, Burma. After a 200-mile trip from British territory on three Royal Indian Navy motor launches, Eifler and his commandoes transitioned to small boats and paddled toward shore. They faced choppy seas; waves as high as 15 feet churned over and among some of what Eifler later described as the “nastiest” rocks he had ever had “the pleasure to behold,” to say nothing of the plumes of sludge—“mud volcanoes”—belching from the seafloor along the coast. Eifler ordered his scout to find a way to shore; when he balked, Eifler unclipped his gun belt and jumped into the water himself.

He swam through the rocks and walked on coral, then secured a long tow line to four rubber boats full of men and about 1,000 pounds of equipment and manhandled the load toward the beach. Forming a human chain from the water’s edge, Eifler and the five or six commandoes quickly unloaded the gear. When they were ready to move inland, Eifler shook hands with each man and told him not to be captured alive.

By now dawn was not far off; Eifler and the boats needed to be gone before a Japanese patrol spotted the telltale signs of a landing. But getting out was as hard as getting in. Once again Eifler manned the ropes, gathering together a fistful of bow lines, then headed out to sea, only to have two of the lines slip from his grasp. Once, twice, three times he jumped into the water—first to round the boats up before the powerful current carried them away, then to free his own craft, a small dinghy, from the rocks that lay between the shore and the open ocean. He regained control but from start to finish was battered against the rocks, hitting his head hard and often enough to leave him dazed and bleeding. That he made it back to the motor launches in the dark with all of the small boats is a testimony to his strength and determination.

The incident marked a turning point for Eifler; he did not bounce back. Headaches, seizures, and blackouts would plague him the rest of his life. Still, there was never a sign of weakness in his wide-set blue eyes or in his voice, said to have been louder than a circus barker’s yell. Having by now advanced to the rank of full colonel, he did not want to go on sick leave, let alone relinquish command. Treating himself with morphine and bourbon, Eifler remained at the helm. Before long, even his supporters had to admit that his behavior was becoming increasingly erratic; in December 1943 Donovan flew out to India to assess the situation for himself. As Donovan told Stilwell, he had decided that Eifler would be going to Washington for a “brief refresher course in our work”—a face-saving way of saying that Eifler was being relieved of command.

DONOVAN SOON SOFTENED the blow by making Eifler a special projects officer, eventually giving him the title of commander of the Field Experimental Unit (FEU)—charged with exploring missions impossible out of OSS Headquarters. Early on came a query about kidnapping Werner Heisenberg, the Third Reich’s leading atomic scientist, at the behest of the Manhattan Project behind America’s own quest for the atom bomb. The dutiful and humorless Eifler accepted the mission without hesitation and was willing to undertake it himself, even though he was a wildly inappropriate choice for the job. Eifler was an intelligent man, but one with an authoritarian streak whose last resort was often brute force. This operation called for a lighter touch; it was likely to play out in a city in neutral Switzerland, not on a jungle battlefield.

This fact was not lost on Donovan. The general loved conflict, but not when it came to running the OSS. He found it hard to say no to a fellow combat veteran, especially one who was willing to do what others were not. So throughout the last days of winter and most of spring in 1944, Eifler found himself weighing possible courses of action. One option had him seizing Heisenberg and manhandling him onto an American plane that would land secretly in a quiet alpine valley. The plane would then spirit captive and captor out of the country—reportedly to parachute into the Mediterranean Sea, where an American warship would pick up the two men.

Eifler remained on the Heisenberg operation until OSS management had had enough of his strong-armed approach. In March 1944 he caused a stir at an airbase in Africa. In the words of an official report, he was guilty of “impatience and improper language toward military personnel,” who were angry enough to refer the matter to the OSS inspector general. It was hardly the right sort of behavior for a man on a secret mission in Europe. To make matters worse, Donovan learned in June that a British officer had filed a formal complaint recommending that the OSS discipline Eifler for talking too freely about his work.

Eifler’s personnel file shows that Donovan formally reprimanded the colonel but let him down gently. The two met in person at least once, but probably twice: in Algiers between June 19 and 25, 1944, and then a few days later in Washington. First, Donovan told Eifler that the mission was off. Then, almost as if he feared the consequences of idling Eifler, Donovan allowed the colonel to choose his next mission and, from the summer of 1944 on, channel his prodigious energy in another direction the OSS had briefly considered earlier in the war.

This was Project Napko, in which the FEU would run paramilitary operations in Korea—a country that had been a de facto Japanese colony since 1910 and was, like Japan itself, largely a closed book to American planners even after more than three years of war. In a comprehensive memorandum that he would forward to Donovan on March 7, 1945, Eifler laid out the many details he and his men had considered. He began with an ambitious, even grandiose, statement of purpose that envisioned the possibility of revolution growing from this small-scale operation:

This is a plan…for the immediate penetration of Korea and ultimately of Japan by a small group of agents…for the purpose of espionage, organization, and, finally, sabotage and armed resistance…which will eventually, if directed, embody the support of twenty-three million [Korean] people for an active revolutionary movement.

Though disappointed to be pulled from the Heisenberg operation, Eifler threw his heart into Napko. The concept, after all, was not unlike that for Detachment 101. The OSS would recruit, train, and infiltrate a small number of agents of Korean origin into Korea, much as Det 101 had worked with the Kachins in Burma. Leveraging the population’s supposed hatred for their Japanese overlords, the agents would recruit sub-agents and meld them into networks. With luck, these networks would spread to the Japanese home islands, where communities of Korean laborers could—at least in theory—harbor agents of Korean origin without drawing notice.

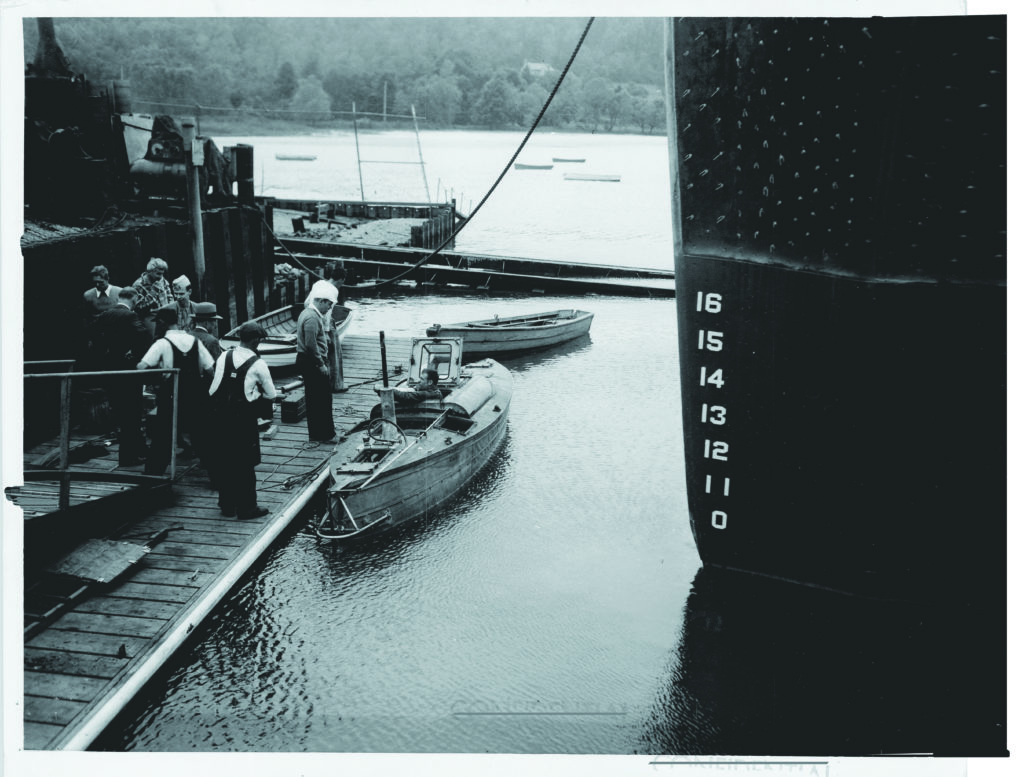

Though the exact origin of the term is no longer part of the record, “Napko” may have been an acronym for “Naval Penetration of Korea.” The operation certainly did have a naval aspect, one remarkable enough to attract the attention of two scholars writing for the CIA in-house journal Studies in Intelligence in 2014: how did the agents plan to get in and out of Korea? There were two options, each of which started with transportation by a full-sized U.S. Navy submarine into Korean waters.

The first called for the agents to exit the submarine while submerged at a shallow depth. Each would have an uninflated nylon boat strapped to his back; after floating to the surface, he would inflate the boat while treading water and trying to keep his gear from drifting away, then get inside and paddle ashore. This was the low-tech plan.

The high-tech option was Gimik, the wooden semi-submersible. The record is silent on the name of the individual to come up with the idea, but Eifler’s subordinates and biographer regarded him as the project’s sponsor. By February 1945, it was under development at a boatyard on the East Coast—almost certainly John Trumpy and Sons of New Jersey, builders of many esteemed wooden vessels including the presidential yacht, USS Sequoia. By June 1945 the boatyard delivered two Gimiks to the OSS, which had recruited two young ensigns, George McCullough and Robert Mullen, to serve as operators.

The first step in a combat deployment would be to carry the boat in a kind of hangar on the deck of the full-size submarine. After surfacing at night as far as 50 miles from the target coast, the crew would load Gimik with about 100 pounds of equipment and up to three men—two agents and an operator—then release it to chug to shore. Upon landing, the agents would unload the gear and proceed inland, leaving the operator to get back out to sea and, with luck, to rendezvous with the submarine.

Eifler wrote that one of the landing sites under consideration was so secluded he would not hesitate to accompany the commandoes ashore, as he had in Burma. He envisioned shoehorning his bulk into Gimik’s tiny cargo space. This was not a good idea. Picture the oversized Eifler, subject to occasional seizures and blackouts, along with two heavily armed men, equipment, and machinery in a dark space about the size of a broom closet—one filled with gasoline fumes—all pitching and rolling in the open ocean, possibly for hours on end.

Gimik was ingenious by World War II standards but would not pass muster by today’s safety-conscious and well-equipped military. On friendly shores and in good weather, Gimik was challenging enough to operate. Especially when running with decks awash, the operator could barely see over the bow to steer. On at least one test run of a Trumpy boat nearly identical to Gimik, the gasoline fumes ignited, shooting the operator out the (mercifully) open front hatch like a rocket. Now factor in the need to operate at night, in cold or rough water, off an enemy coast. The average man’s hands might tremble from the strain; it would take a superhuman effort to stay focused and perform the plan’s many tasks. And if something went wrong and Gimik washed up on a beach, its presence would betray the mission. Years after the war one of the operators, Ensign McCullough, admitted that piloting the boat was a high-risk proposition but added lightly that, at 19, he had been too young to be afraid.

All of this presumes that Korea was enough like Burma for it to make sense for Eifler to try to replicate the success he had enjoyed there. But Korea was not Burma, where Japan had had just a few months to consolidate its control. Generally more open, the Korean countryside did not offer the protection of the Burmese jungle, and the Japanese had had more than 30 years to modernize the country.

The Japanese had superimposed an infrastructure—including roads and communication nets—on the peninsula. There was a large and efficient police force, estimated to be 60,000-strong, in addition to 86,000 soldiers. While many Koreans resented their Japanese overlords—there is no doubt that they were second-class citizens—many others had made peace with their occupiers. It would be difficult to know who would, or would not, report any newcomer, especially a large Caucasian.

The intelligence behind the plan was as thorough as circumstances allowed. Eifler began by inserting an American master sergeant of Korean origin into the POW compound at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, which housed a number of Koreans captured while serving with the Japanese army. The master sergeant posed as a prisoner himself, and for 40 days he simply listened to what the Koreans were saying about conditions at home. This intelligence was folded into the plan along with information from the OSS’s Research and Analysis Branch.

Next came the selection of agents, a more difficult process than anticipated. Though Eifler hoped to recruit about 50 agents, the initial cohort numbered only eight. Most of them had found their way to the United States well before the war. One came from the ranks of the POWs at McCoy, five were in their 40s, and one volunteer was even 50—well past the age of the average Allied commando. Apart from the POW, most had little to no military experience.

Once recruited for Eifler’s operation, the agents shipped off for training at small OSS camps on rugged Catalina Island, 20 miles offshore of greater Los Angeles. The OSS had begun leasing parcels there in late 1943; Eifler’s FEU occupied two isolated locations and a boat ramp.

The training was comprehensive. Starting in February 1945, it covered some 50 topics including standard military subjects (firearms, map reading, tactics, radio procedures) as well as unconventional warfare (invisible inks, boat-handling, dealing with locals), to say nothing of a great deal of physical conditioning. Eifler deemed the teams ready to deploy by early August 1945, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the Napko plan for transmission to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the commander of the Pacific Ocean Areas, where the operation would unfold.

Nimitz’s staff was lukewarm about the idea. But their attitude made no difference after the United States dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Japan surrendered in mid-August. The Napko teams were disbanded—and so, too, was the OSS by the end of September 1945.

WOULD PROJECT NAPKO have succeeded? The prospect seems unlikely. In World War II, no combatants had much success in covertly penetrating an enemy homeland. Sending in the occasional spy was one thing, but a group of armed spies charged with sabotage and revolution was quite another matter. Most Allied commandoes who succeeded did so in occupied territory—in North Africa, for example, where the British emerged from the trackless desert to strike at the Afrika Korps, and in France, where British and American teams took on the German occupiers alongside the French Resistance.

When it came to trying to penetrate Germany in late 1944 and early 1945, British intelligence took a step back, declaring the task too risky. The OSS accepted the challenge and had mixed results after parachuting teams into Germany and, notably, Austria—then part of the Reich. Korea was not unlike Austria: it was part of Japan’s so-called “Inner Zone,” but still distinct from the home islands. So Napko might have enjoyed some success. But given the project’s small size and immense challenges, any triumphs would likely have been offset by failures, as well as the deaths of Eifler’s aging commandoes.

Instead, everyone involved survived the war. Eifler continued to struggle with seizures and memory loss, enduring long periods of hospitalization in 1945 and 1946. Perhaps to atone for wartime guilt (he commented more than once that members of Det 101 had committed war crimes), he eventually received degrees in divinity and psychology from Jackson College, a small missionary school in Hawaii. In the 1950s Eifler went on to earn a PhD in clinical psychology at Chicago’s Illinois Institute of Technology, and then worked for the Department of Health in Monterey County, California, where he developed a reputation for compassion and engagement. He died in April 2002 at the age of 95.

As for Eifler’s Gimiks, they traveled across the Pacific in the summer of 1945 only to be abandoned on a U.S. Navy base in Okinawa and then, many years later, shipped back to the U.S. East Coast as curiosities. One is still the star of a small display at Battleship Cove in Fall River, Massachusetts. Its sister was said to have made it to the U.S. Naval Station in Newport, Rhode Island, where it has since been lost to history.

But American spies would not forget Eifler’s concept. Early in the Cold War, the CIA would ask Trumpy to make two slightly modernized Gimik-like craft, to be known this time around by the code name “Skiff.” Like their predecessors, the semi-submersibles were tested but never deployed on a mission overseas. The CIA has not explained why, leaving the historian to speculate that this project, too, was either overtaken by events or superseded by better technology. Like the Gimik in Fall River, the remaining Skiff’s current mission is to serve as a display, this one in the CIA Museum—another testament to ingenuity and initiative but not, perhaps, to sound judgment. ✯

This story was originally published in the August 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.