Had Hans-Joachim Marseille lived and fought today rather than in 1941 and ’42, there’s not a saloon in the country that would serve him a Bud Lite without carding this scrawny, baby-faced boy. And then they probably would reject the ID as fake. It is impossible to imagine that someone so young, and who looked even younger, could be arguably the finest stick-and-rudder fighter pilot the world will ever know. Jochen, as he was less formally known, shot down 26 airplanes while he was 21 and a further 132 at age 22. Only 18 months elapsed from first boy-pilot shoot-down to his own death as a weary, prematurely aged warrior.

Yes, there were German pilots who racked up higher scores, though no Allied aviator came within a country kilometer of Marseille’s 158 kills. But the victims of Luftwaffe pilots such as 352-victory Erich Hartmann were largely Soviet farmboys flying outmatched Yaks and clumsy Ilyushin bombers on the Eastern Front, easy meat for Germans who’d been flying since the Spanish Civil War aboard far better airplanes.

Hans-Joachim Marseille’s victories were entirely against capable Western pilots, for the most part flying airplanes reasonably matched against his Messerschmitt Me-109E, F and ultimately G. He was the highest-scoring Luftwaffe pilot on the Western Front, and to this day many Germans insist that despite his often having to force-land or bail out as the result of incidental battle damage, he was never beaten by an Allied pilot in a one-on-one dogfight. However, in his book Aces of the Reich, Luftwaffe historian Mike Spick writes, “…in April 1941…the Gruppe deployed to Libya. An area with a distinct lack of women helped Marseille keep his mind on his work. Not that his arrival was auspicious; within days he was shot down by a Hawker Hurricane flown by an elderly Free French pilot [James Denis of No. 73 Squadron, RAF].” Marseille’s record against Hurricanes, Super marine Spitfires and Curtiss P-40s flown by British, Australian and South African pilots, first during the Battle of Britain and then in the North African desert campaign, was nevertheless unrivaled.

Marseille may have flown once or twice against American pilots attached to a British squadron, and possibly even shot down one. But had he met full U.S. Army Air Forces units, it would at least initially have been a horrible mismatch, with the Luftwaffe running roughshod over the Yanks. Marseille died little more than a month before U.S. forces landed in North Africa. When they did, the Luftwaffe easily continued to maintain near-total air superiority. It wasn’t difficult. Early on, American pilots in North Africa lost almost twice as many planes to crashes and accidents as they did to combat.

Marseille…what a strange name for a German. Former French Huguenots in fact made up a considerable portion of Germany’s population, having fled religious persecution by Catholics in 18th-century France. This was particularly true in Berlin, where Jochen was born. Still, some Germans pronounced his name phonetically, “Mar-SAIL,” rather than the more common “Mar-SAY.”

Tomayto tomahto, Marseille came from a military family, as did many Huguenots. So he enthusiastically started flight training in November 1938 but quickly proved to be a screw-up: He did a show-off first solo in a Focke Wulf Fw-44 Stieglitz (the Luftwaffe’s Stearman) by tossing the biplane around as though he was on the tail of an imaginary foe. Bad idea. For this and many other transgressions, Marseille remained a noncom until well into his combat career, while virtually every other pilot in his class, squadron and generation had been promoted to officership and was climbing in rank.

It didn’t help that while still a student pilot he landed on an empty stretch of autobahn during his second cross-country solo in order to take a pee. Some farmers working in a nearby field, being “good Germans,” got his tail number and reported him.

That Marseille wasn’t simply washed out probably could be attributed to the fact that his father was in line for promotion to flag rank, but apparently little of the family’s military tradition rubbed off on the prodigal son. Marseille was lazy, a skirt-chaser, a good drinker, a fan of American Negro jazz, and he abhorred what he considered pointless regulations. Being a Berliner didn’t help—that was like being a Manhattanite among rural Southerners. And that’s not an entirely unlikely metaphor. When Marseille was a high-scorer in Africa and had a privileged multi-tent compound, he somehow managed to get a handsome black South African POW named Mathias as his valet to reinforce his image of himself as a cool Jazz Age dude.

“Marseille’s love of jazz was a significant thing in Nazi Germany,” says Robert Tate, a 15-year U.S. Air Force KC-135 and AWACS pilot and currently a Delta first officer flying 757s and 767s. Tate’s book Hans-Joachim Marseille: An Illustrated Tribute to the Luftwaffe’s Star of Africa was released in July. “It was more than that he just liked the music. There were counterculture groups inside Germany like the Swing Kids [who were the antithesis of the Hitler Youth]. I can’t prove that Marseille was a member of the Swing Kids, but his hair, his dress, his scarf, the shag pipe he often had, the music, his mannerisms, his sexual promiscuity…if he was not a member of the German Swing Kids, he was at least sympathetic. Which was a big statement for a German officer. And Marseille’s friendship with Mathias flies counter to Nazi doctrine toward blacks.”

Marseille’s idea of a uniform was to add whatever seemed hip and Berlin-fashionable at the moment. Even after he was assigned as a squadron pilot he was derided for wearing colorful civvie scarves. Until he became an ace many times over, that is, when wearing scarves suddenly seemed the thing for other pilots to do as well.

Whatever gunnery training Luftwaffe pilots got, it seemed to have little effect on Marseille, who had his own ideas about how to attack and shoot. It took awhile, but he ultimately became a master of deflection shooting—the concept of leading a target and letting it fly into one’s bullets rather than simply hosing it from behind or even dead ahead. In fact he eventually learned that the optimum time to pull the trigger was just as the target disappeared under his Messerschmitt’s nose, if both airplanes were pulling Gs in a turning battle (which was normally the case among fighter pilots who knew what they were doing). Marseille understood that if he fired while turning hard, the course of his bullets was actually downward relative to the path of his own airplane; they in effect “fell” somewhat from the gun barrel.

Interestingly, the only WWII air forces that seriously trained pilots in deflection shooting were those of the U.S. and Japanese navies. Both flew radial engine fighters with short noses and better over-the-cowling views. “With a long nose [like an Me-109’s], particularly if you’re sitting low in the cockpit, you can only see a degree or so below the longitudinal axis of the airplane,” says Robert Shaw, a former F-4 and F-14 pilot and author of the authoritative textbook Fighter Combat: Tactics and Maneuvering. “So you couldn’t pull a lot of lead in a turn, because if the target is turning, you have to turn too, to keep your nose out in front of him, and that puts him underneath your nose so you can’t see him.

“Marseille would most likely have established himself in the plane of his target’s turn and then dragged the pipper through and out in front of him,” Shaw opines, “and when the target disappeared below his nose, he knew he had about the right amount of lead and would start shooting. That worked as long as the target kept turning at the same rate, which apparently they mostly did.”

Unlike pilots who adhered to Manfred von Richthofen’s doctrine, which held that the best attacks were those the enemy never saw coming, Marseille preferred to mix it up with his opponents. He was like a boxer who jumped in and flailed away, a windmill of punches, the instant the round started. When attacked, groups of RAF airplanes often went into Lufbery circles, everybody orbiting so that each airplane had a buddy covering its tail while it covered the airplane ahead. Marseille dived right into the Lufberys, sometimes even joining them for several minutes at a time. (An Me-109 a quarter-mile ahead, seen from behind, doesn’t look all that different from a Hurricane.)

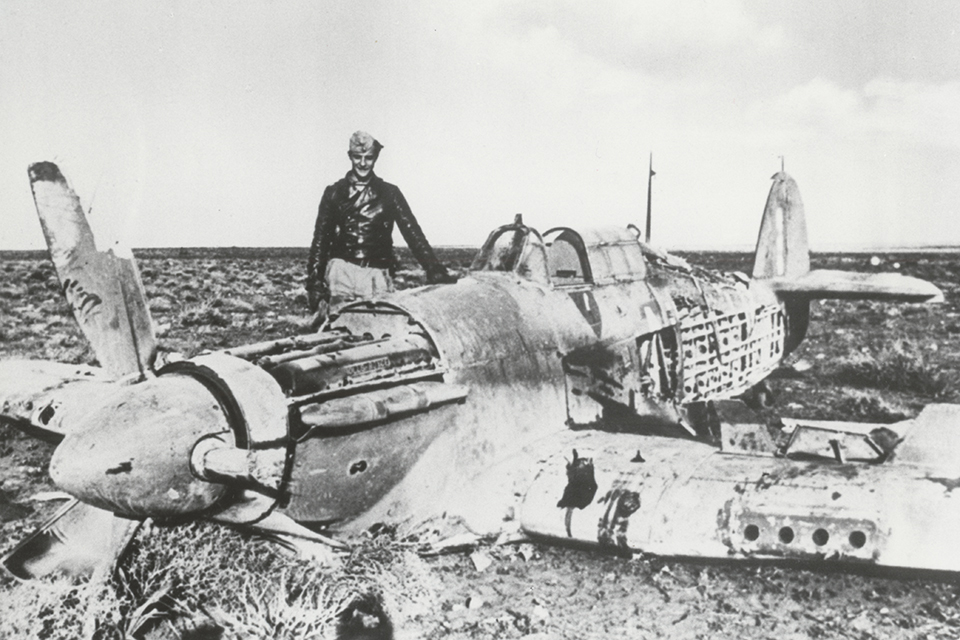

Marseille first saw combat in the Battle of Britain, and he got pummeled, constantly bringing home bullet-filigreed Messerschmitts and sometimes not bringing them home at all. He bailed out over the Channel six times, three of them near the same air-sea rescue base at Cape Griz Nez. The doctor in charge there once told him that next time he needed them, he should make a reservation. Marseille was not amused, seeing the casual joke as a slur on his ability.

His squadron commander wasn’t amused either. Even though Marseille had shot down a Hurricane on his first-ever combat mission and had made five kills by the time he’d flown his fifth mission, he was costing the Luftwaffe valuable planes. He was the aerial equivalent of a Formula 1 driver who is incredibly fast but destroys his cars. In fighter pilot terms, he needed to work on his SA—situational awareness, that priceless eyes-in-the-back-of-your-head ability that allows a good combat pilot to simultaneously assimilate and process the positions and vectors of a variety of threats.

He was also a pain in the ass—disobedient, casual, a goof-off, a braggart who boasted openly of having nailed a well-known actress at a time when his squadron mates must have wondered if he’d ever actually nailed anybody. So what did his squadron commander do? He transferred Marseille to hot, dusty, miserable North Africa, where the pilots lived in tents and baked in the sun.

End of story? Not quite.

Jochen Marseille became a member of a vigorous fighter group, I Gruppe of Jagdgeschwader 27, led by Eduard Neumann, himself so showy and eccentric that he lived in a big circus wagon he’d found in France and shipped to North Africa. Across one side was painted the legend Neumanns bunte Buhne (Neumann’s colorful stage), and here his pilots often gathered to drink and do what carousing North Africa afforded. Neumann was an old hand who had flown in the Spanish Civil War, and he saw in Marseille the bravery and stick-and-rudder talent to mold into a superb fighter pilot, if only he could calm Jochen’s youthful exuberance.

Neumann urged Marseille to slow down, to be patient, to stop simply trying to cheat death on every mission. At one point he even grounded Marseille for three days, exasperated by the endless parade of shot-up Messerschmitts the kid brought home.

Part of the problem seemed to be that in the early stages of his career, Marseille was a Rodney Dangerfield joke: He got no respect. He was a boy, and some of the older hands resented him for his flamboyance and sense of privilege. (The average age of his squadron mates typically was 26, and if you remember your own youth, a five-year age gap was nearly generational.) He really didn’t fit in as a fighter pilot. At least he didn’t think so. Marseille had what parlor psychologists used to call an “inferiority complex.” He wanted to be liked and admired, and he didn’t want to be the object of sarcasm from search-and-rescue medics, the butt of squadron mate practical jokes, the kid who never (at least during the Battle of Britain) got the praise he felt he deserved from his commanders.

While based in France, he once was ordered to fly a Messerschmitt demonstration for a visiting general, since there was no denying that he was the best aerobat in the squadron. He capped his flight off by picking up a handkerchief from a pole, with his wingtip just a meter above the runway. When he landed, he was not congratulated but instead grounded and confined to base for five days for violating the five-meter minimum altitude restriction. (Though it may well have been the general himself who ordered the punishment, nobody rescinded it after the visitor left.)

And Marseille was still a noncom well after he began mowing down Hurricanes and Bristol Blenheims over North Africa. “I’m the oldest Oberfähnrich [senior cadet, essentially] in the Luftwaffe,” he grimly joked. He was finally promoted to Leutnant [second lieutenant] in June 1941, when he had 11 kills.

One of the talents Marseille developed was the ability to quickly change his focus from one target to the next as soon as he fired. He rapidly developed a sense of situational awareness. When ground crews reloaded his magazines, they found that he’d used as few as 10 shots to down an airplane. He used an average of 15 rounds per kill, as recorded by the armorers who serviced his airplanes after missions, and his ability to avoid fixating on a target and hosing it led to a remarkable record of multiple victories. Marseille often shot down two planes on a single sortie and four in a day. On one mission he dispatched six P-40s in six minutes, and two weeks later he notched six kills within seven minutes. He once got seven kills in a day and another time seven in a single mission, but his most spectacular tally was 17 victories in one day (September 1, 1942) during three flights. Surprisingly, that’s not an all-time record: Focke Wulf Fw-190 ace Emil Lang downed 18 Soviet adversaries on November 3, 1943.

Marseille’s end was sadly prosaic and clumsy. He was flying a new Me-109—the latest G model—on September 30, 1942. He’d been quite happy with his 109F and didn’t much like the Gs, as they had a reputation for engine failures. But Field Marshal Albert Kesselring himself had ordered Marseille to switch to the G after the young ace had ignored his squadron commander’s several requests that he do so.

Returning from a routine Stuka-escort mission that met no opposition, Marseille did indeed experience an engine failure, filling the cockpit with smoke. When the fumes and flames became unbearable, he performed the normal bailout procedure—he’d done it many times—of going inverted, opening the canopy, releasing his harness and falling out. The smoke and his stinging eyes had kept him from realizing, however, that the Messerschmitt was already in a shallow inverted dive, descending far more rapidly than its normal speed. (His wingmen estimated that it was doing a good 400 mph.) Marseille was blown straight back into the vertical stabilizer, which either killed him instantly or wounded him grievously enough that he never opened his parachute.

The first medical officer who reached the facedown body on the desert sand turned the dead German onto his back. The doctor wrote in his report: “The finely cut features of his face below a high forehead were nearly undisturbed. It was the face of a tired child.” Hans-Joachim Marseille was just 2l⁄2 months short of his 23rd birthday.

The elephant in the room during any discussion of Jochen Marseille is the big one asking: “Did the kid really shoot down 158 airplanes in a year and a half? Did he really gun 17 in a single day?” Fair questions, considering the most prolific American ace, Richard Bong, shot down a grand total of 40 Japanese, and when the best that David McCampbell, an experienced American pilot flying a 2,000- hp Grumman F6F, could do in the autumn of 1944 was nine victories in a day over 50-hour Japanese kids in aging Mitsubishi Zeros.

Were the Luftwaffe pilots that much better? Look at a listing of top World War II aerial victories by country—Great Britain, its highest-scoring aces with from 26 to 51 kills, Japan’s best 28 to 87, the U.S. 20 to 40 victories. And Germany? The Luftwaffe’s top 16 pilots shot down 192 to 352 enemy planes.

One explanation often offered is that while Allied pilots attacked in groups whenever possible, the Luftwaffe had specialist shooters—Experten, or what we’d have called aces. Pilots such as Marseille were given the chance to make kills as often as possible while their wingmen watched their backs. Hard to imagine an American pilot saying, “You take him, Chuck, you’re so much better than I am…”

Marseille also operated solo or with a single wingman as often as possible; he didn’t want a Schwarm of bumbling squadron mates getting in his way. When there is just one witness to a shoot-down, or perhaps not even one, it’s fair to question the legitimacy of some confirmations.

“In the heat of combat, you can’t waste time verifying claims,” says Fighter Combat author Shaw. “You see pieces coming off the airplane or at least think you do, you think you see smoke coming out of the airplane…if you follow that airplane and watch him until he crashes, you’re going to get shot down by somebody else. Somebody’s going down and it looks like he’s out of control, you claim it. That was true of both sides.”

What set Luftwaffe pilots in particular apart from their Western Front adversaries, however, was the Germans’ “fly till you die” policy. There were no 100-mission tours for Luftwaffe pilots, no honorable retirement from battle to become instructors. They flew until the war was over, until they were injured too badly to fly any more, until they collapsed psychologically or were killed. Not many survived the war.

“One of the things that hurt the Germans was leaving the Experten to run up their numbers and eventually die,” Shaw points out. “It’s better to have a thousand guys making two or three kills each than to have a handful making a hundred.”

American pilots flew a specific number of missions, and if they survived, they were sent home. (The number varied according to the stage of the war, the area of operation and unit needs.) Pilots could volunteer for multiple tours, and many did, but the serious aces were usually denied this opportunity. The PR downside of having a national hero killed far outweighed the benefits of hoping he might rack up a Marseille-size score. If American aces made it to 20, 30 or Bong’s 40 kills, life for them became war-bond tours, publicity campaigns and serious instructorship.

“The big reason the Germans scored more is that they flew more,” says Shaw. “They stayed in the cockpit forever. A lot of them had started flying before the war, they got good training, they had superior equipment and greater experience. They also fought over their own territory for the most part, and when they got shot down, they’d come back in another aircraft that afternoon.”

“Fly-till-you-die was the biggest single reason so many German aces scored the way they did,” says Marseille authority Robert Tate. “Erich Hartmann flew something like 1,250 combat sorties, and during that time, he engaged the enemy 800 times and fired his guns 500 times. And scored 352 kills. When you look at those numbers, [that kill ratio] is not that far-fetched.”

Apply the same percentages to an American ace who flew 100 combat missions, and he’d have engaged the enemy 64 times, fired his guns 40 times and scored 28 kills. Twenty-seven U.S. pilots scored 20 or more victories during World War II, so the comparative numbers hold even across the spectrum of great-to-superb fighter pilots, whether German or American.

Shaw thinks that the overclaiming rate “was typically between two and three times what was actually true, if you go back and look at the number of losses versus claims. And that was true on both sides.”

“Did Marseille overclaim?” Tate muses. “Yeah, he probably did. He’s been my hero for 30 years, but I can be honest and say he did overclaim. As did probably every fighter pilot in World War II. Marseille was especially susceptible to overclaiming, since he was more interested in using minimum ammunition rather than totally obliterating enemy aircraft.” Some planes that Marseille was convinced he’d finished off almost certainly made it home. “But even if Marseille did overclaim and other pilots did so at similar rates, he still destroyed seven and a half times as many aircraft as the highest-scoring Allied pilot in the desert theater and more than twice as many kills as the next-highest Luftwaffe pilot. Marseille was still the real deal.”

In a world in which air combat will never again experience enormous multi-aircraft dogfights, gunfighter Hans-Joachim Marseille may also have been the last of a unique breed.

For further reading, frequent contributor Stephan Wilkinson recommends: Hans-Joachim Marseille: The Life Story of the Star of Africa, by Franz Kurowski; and Hans-Joachim Marseille: An Illustrated Tribute to the Luftwaffe’s Star of Africa, by Robert Tate.