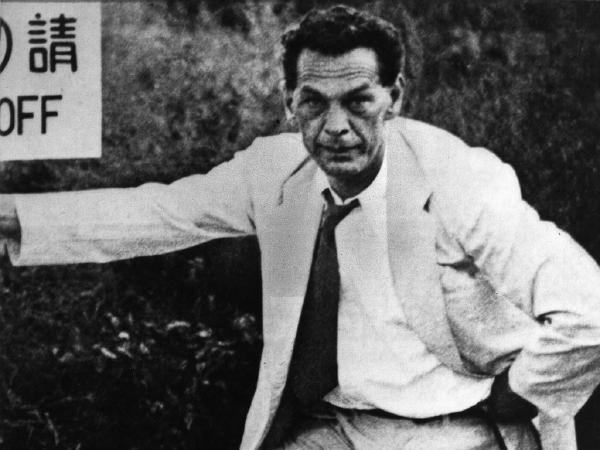

Richard Sorge had just returned to Tokyo on June 22, 1941, when he heard the report, being shouted by newsboys in the street, that Germany had invaded the Soviet Union. Sorge, a prominent German journalist, notorious womanizer, and heavy drinker, had earlier been driving through the countryside with his latest paramour, a beautiful German pianist. Now, sitting at the bar at the Imperial Hotel, he sank into a black mood and became belligerently drunk.

“Hitler’s a f – – -ing criminal,” he shouted in English. “A murderer. But Stalin will teach the bastard a lesson. You just wait and see!” Neither the Japanese barman nor Sorge’s drinking companion could calm him. From a public telephone in the lobby he dialed the German embassy. “This war is lost!” he shouted to the startled ambassador Eugen Ott, a longtime friend.

Sorge’s rage was fueled in part by hatred of war (he had served in the German army in the First World War and was grievously wounded) and by his belief that Hitler’s attack would lead to disaster. But there was another, more potent, reason for his anger. For Richard Sorge—the German journalist, Nazi Party member, and part-time press officer in the German embassy—was in fact an officer in the Soviet foreign military intelligence service, the GRU, and the most important Soviet spy in Asia. And just weeks earlier, his warnings to Moscow of the imminent German attack had been ignored.

On a dispatch he sent the GRU on June 1, which read, “Expected start of German-Soviet war around June 15 is based on information Lt. Colonel Scholl brought with him from Berlin…for Ambassador Ott,” Sorge’s superiors in Moscow had written, “Suspicious. To be listed with telegrams intended as provocations.” An earlier warning from Sorge was contemptuously dismissed by Stalin as coming from “a shit who has set himself up with some little factories and brothels in Japan.”

Sorge nonetheless continued his espionage work—and after the shock of the German attack proved him right, Moscow began heeding his reports. Within a few months, the activities of this man, who many regard as the most important spy of World War II, would provide information that enabled the Soviets to halt the Nazi blitzkrieg at the gates of Moscow, and altered the course of the war.

He seemed custom-made for the role. Richard Sorge was born in 1895 in southern Russia. His mother was Russian, his father a German engineer. The family moved to Germany a few years later, where the boy was raised in an upper-middle-class home. But his Russian origins exerted a lifelong influence. In 1914, Sorge enlisted in the German army. While recuperating from shrapnel wounds that shattered his legs and left him with a lifelong limp, he seduced—and was seduced by—a nurse. She and her father, a physician and a Marxist, introduced Sorge to radical ideas. He spent the next few years studying economics and political science, and Marxist ideology.

At the end of the war, radicalism of all stripes was rampant in Germany, and Sorge veered leftward. He earned a PhD in 1919 and in the same year joined the German Communist Party. Sorge plunged into leftist propaganda work among some German coal miners with whom he had taken a job. He also plunged into an affair with the wife of one of his former professors.

Sorge was both handsome and charismatic, irresistible to women and admired by men. Such was the case with the Gerlach household. Years later Christiane Gerlach described her first sight of Sorge: “It was as if a stroke of lightning ran through me. In this one second something awoke in me that had slumbered until now, something dangerous, dark, inescapable….” Sorge also charmed the professor, Christiane’s husband, who agreed to an amicable divorce, and Sorge and Christiane married in 1922. It lasted only a few years.

Sorge’s leftist agitation got him in trouble with the police, and in 1924 he fled Germany for the new Promised Land—Soviet Russia. There he joined the Soviets’ new international arm, the Comintern (short for Communist International), working as a liaison with foreign communist parties. In 1929, he began work as a military intelligence officer, and the GRU assigned him to work in China. He was instructed in the political and military aspects of his new position as well as the fundamentals of clandestine trade craft. Ever a magnet for women, he took as a lover an attractive drama student, Katya Maximova. After three productive years of espionage work in China, Sorge returned to Moscow in 1933, where he married Maximova, a decision that would bring her grief.

After Japan’s conquest of Manchuria in 1931–32, Moscow feared that Japanese aggression might turn toward the Soviet Far East. Sorge’s assignment was to set up a network in Japan and reveal Japan’s intent toward the Soviet Union. To establish his cover as a journalist, he traveled there via Germany, where a newspaper editor who agreed to accept his articles gave him a letter of introduction to a German army officer, Col. Eugen Ott, the new military attaché in Tokyo.

Sorge arrived in Tokyo in September 1933. His newspaper articles helped establish his credentials as an expert on Japan. He also joined the Nazi Party. In this way, he gained access to the German embassy, where diplomats—including the ambassador to Japan at the time, Herbert von Dirksen—came to value his opinions and analysis.

Sorge did not pretend to be an ardent Nazi. He often voiced scorn for Nazi excesses and the stupidity of some party leaders. Curiously, this enhanced, rather than undermined, his credibility. Surely someone who dared speak his mind so freely could be only what he appeared to be—a serious scholar and patriot whose blunt words and war wounds attested to his authenticity. Another aspect of Sorge’s “cover” was equally genuine: his penchant for heavy drinking and chasing women. An American journalist and bar-hopping companion wrote later that Sorge “created the impression of being a playboy, almost a wastrel, the very antithesis of a keen and dangerous spy.”

In October 1934, Colonel Ott invited Sorge to accompany him on a tour of Manchuria. Sorge wrote a trip report, which Ott forwarded to the high command in Berlin, where it won praise. Sorge became Ott’s most trusted adviser on Japanese politics and was welcomed in Ott’s home—and before long, into the bed of Helma Ott, the colonel’s wife. That Sorge would choose to jeopardize his relationship with the military attaché was surpassed in improbability only by the fact that when Ott learned of the affair, he chose to overlook it, believing, correctly, that it would soon blow over. Ott valued Sorge’s insights into Japan too highly to allow this indiscretion to ruin their relationship. One of Ott’s favorite epithets for Sorge was “der Unwiderstehliche”—the Irresistible. The colonel, too, had fallen under Sorge’s spell.

Sorge’s Tokyo network included two other agents sent by Moscow. Branko Vukelic, a Yugoslav communist, worked as a journalist for a French news agency and handled microfilm work for Sorge. Max Clausen, a German communist, was the ring’s radio operator. Clausen sent dispatches in a numerical code using a one-time pad, a cumbersome but virtually unbreakable code system that relied on a secret, random key. Japanese authorities discovered the unauthorized radio transmissions, but were unable to pinpoint the source or decipher the code.

The ring’s most important member, after Sorge himself, was Hotsumi Ozaki, a left-leaning Japanese journalist. Ozaki was a highly respected expert on China, with influential political contacts. One of his friends was the chief cabinet secretary to the prime minister, Prince Fumimaro Konoye; Konoye later hired Ozaki as a cabinet consultant. Ozaki moved into an office in the prime minister’s official residence, where he had access to classified documents and worked on foreign policy reports and recommendations for the government. Ozaki’s information and assessments became key elements of Sorge’s reports to Moscow. In Sorge’s discussions with German embassy officials, he presented Ozaki’s opinions as his own, which further enhanced his stature as a trusted expert.

Sorge lived in a small rented house in a quiet residential neighborhood, within sight of the local police station. This may have been part of Sorge’s unorthodox method, to “hide in plain sight.” He certainly did not give the appearance of hiding. He raced through Tokyo’s crowded streets on a motorcycle at breakneck speed, sober or drunk. In the summer of 1936, he wooed a pretty 26-year-old named Hanako Iishi, a waitress at one of his regular haunts. Before long, Iishi moved into Sorge’s house. It would be the most enduring relationship of his life.

In the spring of 1936, Sorge’s three years of groundwork in Tokyo began to pay off. Eugen Ott learned from Japanese army contacts of secret negotiations between Germany and Japan for what would be known as the Anti-Comintern Pact, a de facto anti-Soviet treaty. The negotiations were conducted in Berlin, and the German embassy in Tokyo was kept in the dark. Ott shared this intelligence only with Ambassador Dirksen, and with Sorge. As a result, Sorge—and the GRU—were kept abreast of the negotiations, which heightened Moscow’s concern that the alliance could threaten the Soviet Union with a two-front war.

In 1938, Ott, who had been promoted to major general, became Germany’s ambassador to Japan. This further enhanced Sorge’s standing in the German embassy. Ott showed him drafts of his cables and reports and asked his opinion before transmitting them to Berlin. The embassy staff took their cue from Ott. As Sorge himself wrote, “They would come to me and say, ‘we have found out such and such a thing, have you heard about it and what do you think?’” The embassy’s police attaché, Gestapo Col. Joseph Meisinger, confirmed that the relationship between Ott and Sorge “was now so close that all normal reports from attachés to Berlin became mere appendages to the overall report written by Sorge and signed by the Ambassador.”

One of Ott’s favorite epithets for Sorge was “der Unwiderstehliche”—the Irresistible. The colonel, too, had fallen under Sorge’s spell.

That June, Gen. Genrikh Lyushkov, head of the NKVD (predecessor of the KGB) in the Soviet Far East, crossed the border into Manchuria and sought political asylum in Japan to avoid Stalin’s bloody purge of the Red Army’s leadership. Moscow was desperate to know what he was telling the Japanese. Berlin had sent an intelligence officer to Tokyo to help debrief Lyushkov; Sorge got the embassy’s copy of the top-secret report. It said that according to Lyushkov, there was strong dissatisfaction and opposition to Stalin in the Soviet Union, and that if Japan struck, the Red Army “may collapse in a day.” Lyushkov had also apparently disclosed Soviet military deployments and codes. Naturally, Moscow changed the codes.

Six weeks later, a Soviet-Japanese border clash erupted at the site of Lyushkov’s defection, sparked by over-aggressive Soviet efforts to seal the border there. Intelligence from the Sorge ring shaped the Soviets’ tough response. Hotsumi Ozaki had learned that Japan’s leaders, preoccupied with their war in China, were determined to prevent this from becoming a large-scale conflict. So Moscow threw thousands of men, with armor and air support, into the battle. After two weeks of fighting, the Battle of Lake Khasan ended with Japan accepting Moscow’s terms.

The same dynamic played out one year later during an undeclared war on the Mongolia-Manchuria frontier. The stakes and the scope of the fighting were far greater this time, but the result was similar. Again, Sorge was able to report authoritatively that the Japanese government was determined that the conflict not grow into a general war. That emboldened Stalin to deal a crushing blow to the Japanese in August 1939 at the Battle of Khalkhin Gol.

At the same time, Sorge kept Moscow informed about Japan’s attempts to draw Germany into an anti-Soviet military alliance. That information contributed to Stalin’s decision to counter the threat by himself aligning late that August with Hitler in the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact—triggering the outbreak of the Second World War one week later. In one stroke, Stalin helped instigate war between Germany, Britain, and France, leaving the Soviet Union safely on the sidelines, and cut Japan off from its Anti-Comintern ally, Germany, allowing him to deal with the Japanese military threat in isolation. Sorge’s reports to Moscow helped shape this strategy. But his greatest service to the USSR was yet to come.

By late 1940, Sorge began to pick up indications of a large-scale German military buildup near the Soviet borders. On December 28, he sent his first serious warning to Moscow about a possible German attack. More would follow.

By early May 1941, Sorge became convinced that war was imminent. He summed up his concerns in a dispatch transmitted on May 6: “Possibility of outbreak of war at any moment is very high…. German generals estimate the Red Army’s fighting capacity is so low…[it] will be destroyed in the course of a few weeks.”

A May 30 dispatch to the GRU began: “Berlin informed Ott that German attack will commence in the latter part of June. Ott 95 percent certain war will commence.”

Then, on May 31, Lt. Col. Edwin Scholl confided to Sorge that 170 to 190 German divisions were massed on the Soviet border and the invasion would begin June 15. On June 1, Sorge sent this momentous news to Moscow. It should have been the most important dispatch of his career. It was this message that was marked “suspicious” and a “provocation” by his bosses.

Aware that his warnings were being disregarded, Sorge tried once more to rouse Stalin from his complacency. On June 20, he drafted this warning: “Ott told me that war between Germany and the USSR is inevitable…. Invest [the code name for Ozaki] told me that the Japanese General Staff is already discussing what position to take in the event of war.” Max Clausen transmitted the dispatch on June 21; the German invasion began the next day, and took the Red Army totally by surprise. The next five months were catastrophic for Russia.

Immediately after the attack, Moscow called on Sorge for urgent help. A curt radio message ordered him to report on the Japanese government’s policy regarding the German-Soviet war. The point was this: if Japan decided to attack the Soviet Far East, a grave situation would become vastly—perhaps fatally—worse. At that moment, Berlin was directing Ambassador Ott to use all possible means to persuade Japan to attack the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union might not survive a two-front war.

Meanwhile, a policy debate arose in Tokyo. Japan was deeply engaged in war in China; but China had vast strategic depth and there was no end in sight. Now, the situation in Europe presented new possibilities. Germany’s victories in Western Europe opened the door for Japan to advance into the resource-rich French, Dutch, and British colonies in Southeast Asia. On the other hand, Hitler’s invasion of Russia invited Japan to strike north into Siberia and the Soviet Far East. Each course entailed risk. Japan, bogged down in China, could not strike south and north. It would have to choose.

Less than a week after the German attack, Sorge accurately summed up the situation for Moscow. He reported that Japan had decided to send troops into French Indochina; that Ozaki believed Japan would wait to see how the German-Soviet war developed; that it would attack north if the Red Army were quickly defeated; but that Ott believed Japan would not attack north for the time being. Stalin’s signature at the bottom of this document indicates that the supreme leader read Sorge’s dispatch, not just a summary of it.

The relationship between Ott and Sorge “was now so close that all normal reports from attachés to Berlin became mere appendages to the overall report written by Sorge and signed by the Ambassador.”

On July 2, an Imperial Conference—a meeting of Japan’s top military and political leaders in the Emperor’s presence—set Japan’s policy. As Sorge informed Moscow, Japan would send its troops into French Indochina, but would also build up its strength in northern Japan and Manchuria to prepare to strike north if the Red Army were defeated.

At the bottom of this document, the Deputy Head of Soviet Army General Staff Intelligence wrote, “In consideration of the high reliability and accuracy of previous information and the competence of the information sources, this information can be trusted.” After Sorge’s warnings of the German attack had proved correct, Moscow, belatedly, believed him.

Later that July, Tokyo’s situation became more complicated when the United States and Britain imposed an oil embargo on Japan. Almost all the oil Japan imported was controlled by the Anglo-American powers and their allies. The oil-rich Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), however, lay within Japan’s reach. That strengthened the arguments of those in Tokyo advocating southward expansion. But the astounding magnitude of Germany’s early victories against the Red Army encouraged those who favored the northward course.

In July, Japanese troops occupied French Indochina. At the same time, Japan sent hundreds of thousands of additional troops into Manchuria, near the Soviet borders. Sorge was unsure in which direction Japan would move, but in the next few weeks he and Ozaki solved the puzzle. On August 25–26, Sorge drafted this message to Moscow: “Invest [Ozaki] was able to learn from circles closest to [Japanese Prime Minister] Konoye…that the High Command…discussed whether they should go to war with the USSR. They decided not to launch the war within this year, repeat, not to launch the war this year.”

On September 6, another Imperial Conference confirmed the decision to expand southward—and prepare for war with the United States and Britain. Ozaki got word of this, and Ott confided to Sorge the total failure of his efforts to persuade the Japanese to attack Russia. On September 14, Sorge reported even more emphatically to Moscow that, “In the careful judgment of all of us here…the possibility of [Japan] launching an attack, which existed until recently, has disappeared….”

Now Stalin finally felt free to make the critical decision to move a large part of his Far Eastern reserves westward. In the next two months, 15 infantry divisions, 3 cavalry divisions, 1,700 tanks, and 1,500 aircraft moved from the Soviet Far East to the European front. It was these powerful reinforcements that turned the tide in the Battle of Moscow in the first week of December 1941, at the same time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

The Sorge ring alone, of course, was not solely responsible for this turn of events. But Sorge played an important part. He had scant opportunity to savor his success, however. His spy network had begun to unravel.

In October, Japanese police brought in for questioning a dressmaker who had been recruited by a sub-agent of Ozaki’s named Yotoku Miyagi. The dressmaker gave up Miyagi’s name. When they hauled in Miyagi, he tried to save his colleagues by leaping to his death through an unguarded window. But the fall was not fatal. Dragged back to the interrogation room with broken bones, he named Ozaki and Sorge as communist agents. On October 18, Sorge was arrested.

After resisting for a week, Sorge agreed to give a full account of his activities in Japan, provided that the authorities took no action against his Japanese lover, Hanako Iishi, and the wives of several of his colleagues, whom he insisted were innocent.

Sorge spent the next three years in Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison. Following months of interrogation, he was tried and convicted of being a communist agent whose espionage activities were aimed at overthrowing the emperor system and private property. In September 1943, he was sentenced to death. Sorge was confident, however, that he would not face the gallows; Tokyo would trade him to Moscow in exchange for a Japanese prisoner. His captors had the same idea. The Japanese tried on three separate occasions to arrange a prisoner exchange. Each time, Moscow’s reply was the same: “The man called Richard Sorge is unknown to us.”

Many countries do not acknowledge their spies. But Sorge was probably doomed for a different reason: he was an embarrassing reminder that Stalin had ignored warnings of the impending German attack. Such a reminder, and witness, would be most unwelcome to Stalin and his regime.

Moscow’s apparent indifference to Sorge’s fate persuaded the Japanese that there was no point in further attempts to trade, or for mercy. On November 7, 1944, Richard Sorge was hanged in Sugamo Prison. He had no way of knowing that his wife, Katya Maximova, had died more than a year earlier. After waiting forlornly for him for years in Russia, she was arrested by the NKVD in September 1942 on charges, surely false, of spying for Germany. She died in a Siberian labor camp a year later. Her real crime probably was being the wife of Richard Sorge.

Sorge’s beloved Iishi fared better. Japanese authorities honored their pledge not to prosecute her, and she was allowed to spend the rest of her life quietly in Tokyo. At her expense, Sorge’s remains were moved in 1949 from the prison graveyard to a grassy cemetery in the Tokyo suburbs.

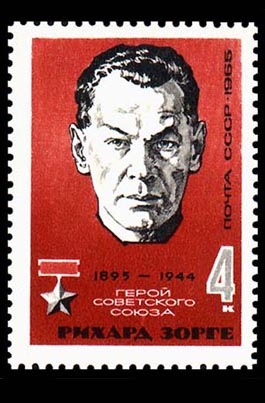

In 1961, a French movie entitled Who Are You, Mr. Sorge? became popular in the Soviet Union. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev saw the film and reportedly asked the KGB whether the story was true. When it was confirmed, Khrushchev awarded Sorge the title Hero of the Soviet Union, its highest honor; Iishi, who died in 2000 at age 89, received a Soviet pension. Today the title is carved into Sorge’s large black marble tombstone, a street in Moscow bears his name, and commemorative stamps were issued in his honor.

In the movie, as in real life, Sorge was no James Bond. Still, he was the person whom Ian Fleming, Bond’s creator and himself a World War II British intelligence officer, judged “the most formidable spy in history.” The intelligence that Sorge provided of Japan’s decision to strike south may literally have saved the Soviet Union from defeat. But ironically, Stalin’s refusal to believe Sorge’s earlier warnings, a decision that so endangered the Soviet Union, doomed its savior to a lonely death.

Stuart D. Goldman is the Scholar in Residence at the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research. Goldman spent a year in Tokyo as a Japan Foundation Fellow researching Soviet-Japanese conflict in the 1930s. His book on the subject will be published by the U.S. Naval Institute Press in 2011. The Russian spy Richard Sorge plays an important part in that story.