They say history is written by the victors, and the 1938 German loss to a French-born Jew René Dreyfus, and his female boss, heiress and speed queen Lucy Schell, had to be destroyed from the annals of history.

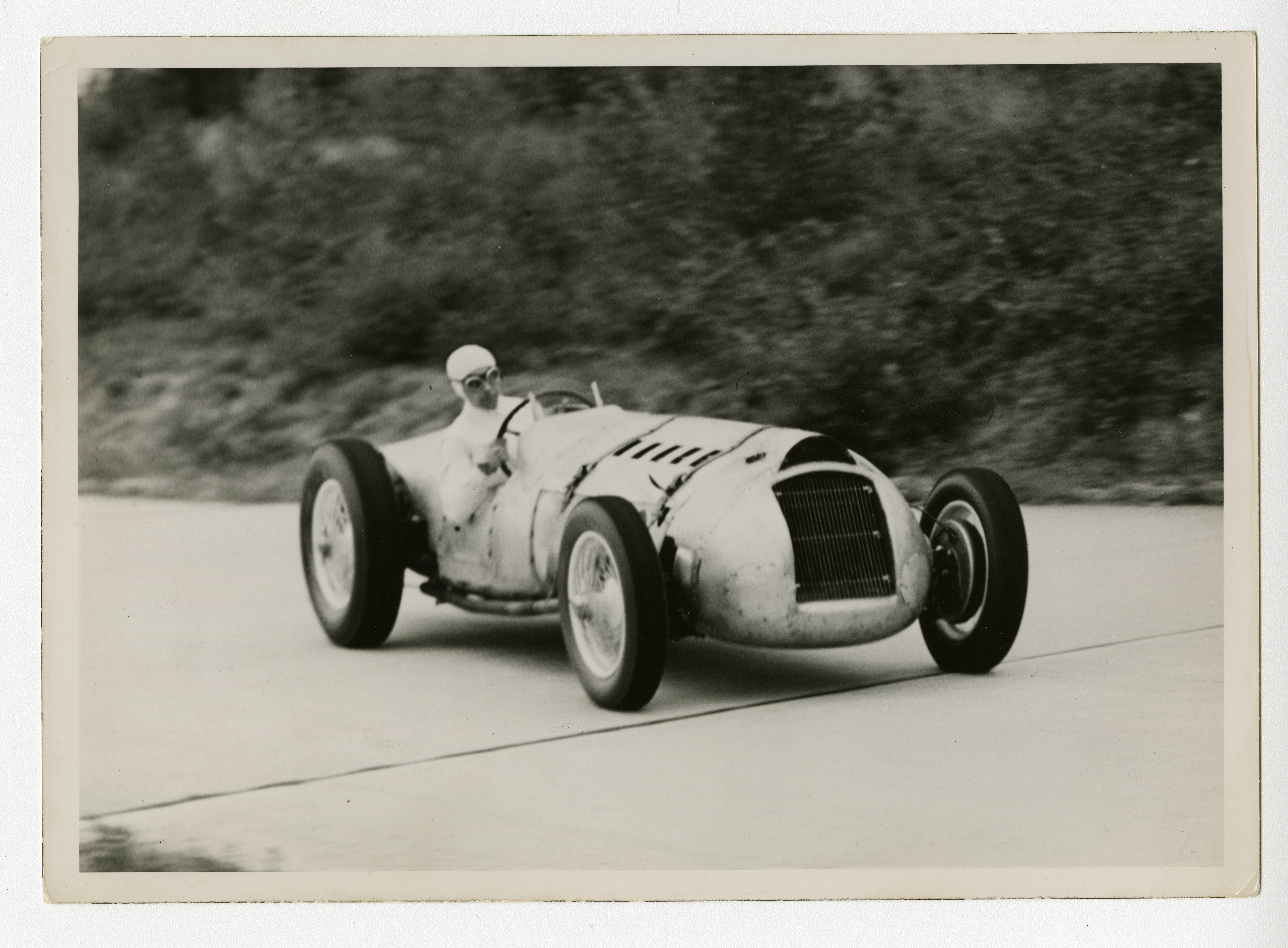

They say history is written by the victors, and the 1938 German loss to a French-born Jew René Dreyfus, and his female boss, heiress and speed queen Lucy Schell, had to be destroyed from the annals of history. The Nazis could not stand what the latter had achieved in defeating Hitler’s Silver Arrow race cars in Pau, France in 1938. With its invasion of France two years later, Germany intended to shred any evidence of its epic loss at the hands of Lucy’s Grand Prix race team—the first and only woman to launch and run such in motor sport. It is an improbable tale, one that barely survived World War II, but Lucy, the pre-war titan of motor sport, always found a way to win.

Born into a wealthy American family, Lucy (née) O’Reilly might have been spoiled into laziness. After all, as an only child, whatever she wanted, she got. But this doting rather instilled in her a confidence to pursue her ambitions brashly—and unapologetically. After the outbreak of World War I, Lucy served in a military hospital in Paris treating the wounds of soldiers from the trenches. The experience steeled her spine.

Afterward, she wed American bon vivant, Laury Schell; enjoyed the party in post-war Paris; and had two boys. Instead of settling her down, motherhood had the effect of revving her up. Laury always had a passion for motor sport, and Lucy caught the bug as well. Thanks to her family money, she could afford to buy the latest, and best, cars—Bugatti, Alfa Romeo, and Talbot.

By the 1930s, she was one of the top female drivers in Europe, but despite her wealth and success Lucy, like other female racers, fought waves of sexism. Organizers spent an inordinate amount of time thinking about what these pioneers should wear (lest, ridiculously, their skirts blow up over their heads), rather than how well they were competing. Editorialists considered them too “weak and delicate by definition” to even brake or steer. Male race-car drivers joked, “They chase after us on the track; we chase after them off it.” Many events continued to forbid women outright. Others only allowed them as co-drivers. They were a rarity in Grand Prix events, and factory teams refused to let them join their ranks.

Lucy played the game—to a point. The press wanted her to drive fast and to be ready for the runway an hour later. Fine, as long as she could race. As for silver-spoon airs or a lack of toughness, she suffered from neither. Before one race, she broke her arm in several places and her doctor advised her to forfeit. Lucy refused, and despite participating with a thick plaster cast on her arm, she almost came in first.

Her favorite event was the Monte Carlo Rally, an endurance challenge that, as one chronicler remarked, appealed to those “looking for trouble.” Blizzards, washed away roads, boar attacks, seized engines, and sleepless nights—all came with the territory. Partnered with Laury, the two flew the Stars and Stripes, and year after year they were the rally’s highest-placed Americans. One journalist, who hitched a ride in the 2,300-mile journey from the tip of Norway to Monaco, noted that the tougher conditions became, the wider the smile on Lucy’s face.

Everything changed when Hitler launched the Third Reich. In one of his first speeches as the leader of Germany, he made clear his intentions to support his country’s auto industry and rule motor sport. Success there would revitalize the economy, raise the prestige of the Reich, and also ready it for war. Millions of marks poured into the coffers of Mercedes, and its rival Auto Union, to field revolutionary new Grand Prix race cars. Nicknamed Silver Arrows, they came to rule every race, and the Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels did not hesitate to make use of their drivers as Reich heroes, who were “swift as greyhounds, tough as leather, strong as Krupp steel.”

By the mid-thirties, Lucy had seen enough. Not the French, nor Italian, nor British, nor Americans, could field race cars to compete. The Nazis were running roughshod over motor sport, just as they were in foreign affairs. Something, Lucy determined, must be done so she decided to hang up her racing overalls and launch her own Grand Prix team from scratch. It was a daring, revolutionary move in the world of motor sport.

First, she needed a race car, one that could stand a chance against the Silver Arrows. For that, she enlisted the most unlikely of manufacturers: Delahaye. At the start of the decade, the stolid, reliably conservative French company was in dire straits, their vehicles known for durability, but by no means speed. One critic concluded that Delahaye built, “the perfect car to drive in a funeral procession.”

To fight off bankruptcy, its board decided to promote the brand by building lighter, faster cars that could compete in sports car competition. It was no matter. In 1936, Lucy stormed into the office of Delahaye’s production chief Charles Weiffenbach and declared that she would be running a crew of drivers in the next Grand Prix. They would be called Team Blue, and she needed race cars. “I will finance the project from top to bottom: design, construction, development, the racing itself. I’m offering you an opportunity which I’m sure isn’t available to any other firm…Now what do you say?”

With Lucy as their foremost champion, they had achieved some impressive success. But building a Grand Prix car was a whole different kettle of fish. Designs often took years and the inevitable growing pains of building such a race car were often perilous to their first drivers.

And while no expenses were spared, Lucy needed a champion driver. Such were few in number, and fewer still were those not already committed to established teams. Lucy was an inspiring force, but even if one of the great could stomach taking orders from a woman, they would never take the leap to drive for an untested, independent operation whose cars were still in development.

She needed someone desperate, someone eager to prove or reestablish himself. One name, and one name alone, came to mind: René Dreyfus.

Dreyfus had once been a top Grand Prix driver, but with the rise of fascism, he was banned from competing with the best teams and the fastest cars because of his Jewish heritage. Lucy knew he was skilled enough to win any race — if he still had the fire to do it — and she was nothing if not a fire-starter. René was brought over to Team Blue by the sheer force of her will.

Drawing on the resolve, dogged preparation, and will to win, Team Blue began their journey. When the Delahaye engineers faltered in their design, she pressed them to continue. When their race car needed to be tested, she unfailingly showed up on the track to take it for a drive. When Dreyfus questioned in his ability, she never faltered in her belief in him.

Few took her team seriously, fewer still that she was anything more than a deep pocket with a vainglorious ambition.

When Team Blue first triumphed in claiming the Million Franc Prize, a 1937 contest to build the fastest French Grand Prix car, people took notice but gave all the credit to Dreyfus and Delahaye. Lucy was all but forgotten.

Team Blue’s greatest battle stood ahead: to beat the Silver Arrows in the opening race of the new formula for the 1938 Grand Prix season. It was a bold gambit since the Germans had reigned supreme in motorsport since the Nazis had determined to invest in Mercedes and Auto Union. Every bookmaker gave Team Blue distant odds. Mercedes barely counted them a challenge. Journalists thought Dreyfus stood no chance at all.

Lucy remained convinced they would win and emboldened Dreyfus to strike a symbolic blow against the Nazis by conquering them on the round-the-houses circuit in Pau, France. David met Goliath and won in the most dramatic fashion. The embarrassing defeat was not one the Third Reich would forget—and Lucy knew it.

As the German army swept across Western Europe in 1940, Lucy sent Dreyfus to America to compete in the Indianapolis 500. It was the only way to keep him safe. Dismantling and secreting away the four Delahaye race cars came next. By June, Lucy and her family had fled the capital as well, first to Monaco, then the United States.

In Paris, the Nazis stole the race records of the Automobile Club de France, including, pointedly, the Silver Arrow loss at the hands of Team Blue.

The attempts to erase the Nazi defeat, however, were unsuccessful. Today, the Delahaye race cars have been restored to their former glory, and the triumph of Lucy Schell and her Team Blue is remembered well.

[hr]

Neal Bascomb is the national award-winning and New York Times best-selling author of The Winter Fortress, Hunting Eichmann, The Perfect Mile, Higher, The Nazi Hunters, and Red Mutiny, among others. His latest book, Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best, is on shelves now.