Editor’s note: In March, MHQ contributing editor Geoffrey Parker was awarded the 2012 Dr. A. H. Heineken Prize "for his outstanding scholarship on the social, political, and military history of Europe between 1500 and 1650, in particular Spain, Philip II, and the Dutch Revolt; for his contribution to military history in general; and for his research on the role of climate in world history." Parker traveled to the Netherlands to receive the award ($150,000 USD) on September 27. In celebration, we’re posting an article he wrote for MHQ in 2005, which describes another momentous trek to the Netherlands.

In November 2012, Parker’s colleagues will publish a collection of essays in his honor, The Limits of Empire: European Imperial Formations in Early Modern World History (Ashgate). Parker’s newest book, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (Yale), comes out in January 2013.

* * * *

The duke of Alba’s 700-mile march to the Netherlands at the head of 10,000 veteran Spanish troops in 1567 marked a turning point in European history. It established a Rubicon for Spanish imperialism: a barrier that, once crossed, transformed the political situation in northern Europe and, with it, the prospects of Hapsburg hegemony on the Continent. It also constituted one of the most remarkable logistical feats in European military history, celebrated in art, prose, verse, and proverb.

King Philip’s royal council warned him: ‘If the Netherlands situation is not remedied, it will bring about the loss of Spain and of all the rest’ of the monarchy

The decision to march arose from the combination of two separate developments: the spread of Protestant ideas—Lutheran, Anabaptist, and above all Calvinist—throughout the Spanish Netherlands despite savage persecution by the central government in Brussels, and the mounting opposition of some noble members of that central government to the policies decreed by their absentee sovereign, Philip II. Until 1559 the Hapsburg king had ruled his vast empire from Brussels, but in that year he departed for Spain, leaving his half sister, Margaret of Parma, as his regent. In his absence, since Philip refused to heed their political advice, a group of Netherlands nobles led by Count Lamoral of Egmont and Prince William of Orange searched for an issue that would broaden their local support and force the king to listen. They chose religious toleration. Although at this time none of the aristocratic leaders was Protestant, they refused to enforce the laws against heresy, and the number and daring of the Protestants in the Netherlands rapidly increased.

On July 19, 1566, Margaret of Parma reported that the Calvinists were meeting in ever greater numbers, their emotions stirred up by ever more inflammatory sermons, which she lacked the troops, the money, and the supporters to prevent. She portrayed the whole country as poised on the brink of rebellion and warned the king that he had only two possible courses of action: Take up arms against the Calvinists or make concessions to them.

Everyone in the Netherlands—whether they supported or opposed the Calvinists—knew that Philip would find it hard to take up arms because the Turkish battle fleet, consisting of more than one hundred war galleys, had left Constantinople that spring. With extensive possessions in Italy, Spain’s king needed to concentrate all his resources on the defense of the Mediterranean until the Turks’ target became known. Under the circumstances he could only buy time. On July 31, confessing weakly that “in truth I cannot understand how such a great evil could have arisen and spread in such a short time,” Philip agreed to abolish the Inquisition in the Netherlands, to suspend the laws against heresy, and to pardon the opposition leaders. A few days later, however, he made a declaration before a notary that the concessions had only been made under duress and were therefore not binding. He also dispatched orders to recruit 13,000 German troops for service in the Netherlands and sent Margaret money to pay for them.

Read More About Parker’s Prize:

Parker’s Prize Citation

Acceptance Speech

Before news of these decisions could arrive in the Netherlands (even the fastest courier took two weeks to cover the 800 miles that separated it from Spain) the situation changed dramatically. In the absence of forceful leadership from the king and his demoralized regent, Calvinist preachers began to urge their congregations to enter Catholic churches and smash all religious images—stained glass, statues, paintings—to “purify” the edifices for Reformed worship. When the first few outbreaks of iconoclasm went unpunished, the movement gathered momentum until by the end of the month some 400 churches and countless lesser shrines all over the Netherlands had been desecrated. Although the perpetrators of the “Iconoclastic Fury” numbered fewer than one thousand, Margaret of Parma hysterically assured the king that “almost half the population over here practices or sympathizes with heresy” and that the number of people in arms “now exceeds 200,000.”

When a courier arrived at court with this stunning news, even before Philip had read the letters in full he went down with a fever. The king had seven seizures in the following fortnight; no important business of state could be transacted. Not until September 22, 1566, did the royal council meet to discuss the Netherlands problem. Everyone present agreed that only force could now restore royal authority, and they appreciated that a failure to act decisively would jeopardize the king’s authority not only in the Netherlands but elsewhere. The council had received urgent warnings from colleagues that “all Italy is plainly saying that if the troubles in the Netherlands continue, Milan and Naples will follow,” and so it advised Philip that “if the Netherlands situation is not remedied, it will bring about the loss of Spain and of all the rest” of the monarchy. Accordingly, they reviewed possible solutions to the Netherlands situation in the context of Spain’s overall military position.

First, they noted a significant improvement in the crown’s finances. The annual “treasure fleet” from Spanish America had just arrived at Seville with more than four million ducats, the highest total recorded to that date. On the political front, too, they saw cause for optimism. For more than a decade, the Turkish fleet had attacked the territories of Spain and its allies in the central Mediterranean, culminating in the 1565 siege of Malta, which the king’s forces had relieved with difficulty. In 1566, however, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent led an invasion of Hungary in person. It seemed unlikely that he would also attack any Spanish possessions that year. The councilors also noted that the governments of France and England, both of which might object to the use of force just across their borders in the Netherlands, were too weak to cause serious trouble.

The council therefore recommended that the king should move 10,000 of the Spanish veterans stationed in Spain’s four main Italian possessions—Milan, Sardinia, Naples, and Sicily—to the Netherlands and that he should raise new recruits in Spain to replace them. The council intended the veterans to assemble in the duchy of Milan by November, ready to march overland to the still-loyal province of Luxembourg, where they would join 60,000 other troops raised locally.

This was a tight timetable, and it depended upon finding a safe itinerary between Milan and Luxemburg for the Spanish troops. Luckily, the council could draw on the experience of Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, an experienced minister of both Philip II and his father, Charles V, who reviewed the various routes available. Granvelle ruled out a passage to the Netherlands through Germany, a route that Philip himself had followed two decades before, because the risk of an attack by Protestants who sympathized with the Dutch rebels now made a repetition too dangerous. For the same reason, Granvelle advised against a march from Milan via Innsbruck to Alsace (ruled by a Hapsburg archduke favorable to Spain) and then to Franche-Comté (ruled by Philip II). Instead, he argued: “The shortest route would be from Genoa through Piedmont and Savoy, crossing the Mont Cenis [Pass]. In fact, it would be more than one-third shorter. The route runs between the mountains between Piedmont and Franche-Comté, which borders on Savoy [on one side] and Lorraine on the other. You can cross Lorraine in four days and reach the duchy of Luxembourg.”

Granvelle added helpfully: “I recall that King Francis [of France] traveled this way with his army and court when he went to relieve Turin in 1527. It is not as hard a road as people claim: I traveled it myself thirty years ago.” Contemporaries would call this route, which would eventually be used by more than 100,000 soldiers in the service of Philip II and his descendants, the “Spanish Road.” On October 29, 1566, the king reconvened his council to make the final decisions on how to deal with the continuing disorder in the Netherlands. Those present restated their conviction that to permit the troubles to continue would “hazard Spain’s prestige” and might be taken as “an example of weakness that would encourage other provinces to rebel.” They therefore concentrated on the question of how much force should be used and who should control it.

Some argued that only a small number of troops would be required, provided that the king went to the Netherlands in person to supervise the repression. No one else, they insisted, could command sufficient respect to make the right concessions from a position of natural strength. To this, however, others raised an unanswerable objection: It was unsafe for the king to go. The maritime provinces of the Netherlands were in ferment and under the control of the most suspect noblemen—the prince of Orange governed Holland and Zealand, and the count of Egmont governed Flanders—which made the sea route to the Netherlands totally impractical. Any attempt by Philip to pass through France, as his father, Charles V, had done during a similar emergency in 1540, meant that he ran the risk of assassination at the hands of the Protestant allies of the Dutch rebels.

It would therefore be better to send the veterans from Italy to the Low Countries along the Spanish Road, commanded by some reliable general who could suppress all sedition. When this had been achieved, the king could follow safely by sea. One of those who supported this strategy was Don Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, the duke of Alba, Spain’s most experienced general. He also stressed that the force used should be sufficient to ensure that those who had defied the authority of king and church would never be able to do so again.

AFTER LONG DEBATE, the king chose the policy advocated by Alba. He therefore appointed ambassadors to ask the dukes of Savoy and Lorraine to allow his troops to pass through their territories on the way to the Netherlands. He also ordered the governor of Milan to dispatch surveyors and a “man who can make a good painting to show the nature of the area through which the troops will pass,” in order to chart and construct an itinerary through the Alps suitable for the Spanish army. A few days later an experienced military engineer left Madrid to ensure that the roads and bridges leading to and from the Mont Cenis Pass would be adequate for the great expedition.

At this point there was still no agreement on who should command the army. The duke of Alba, the obvious candidate, ruled himself out because of his advanced age (he was sixty in 1566) and his indifferent health (gout had kept him immobilized for much of the autumn). The king therefore offered supreme command first to the duke of Parma (Margaret’s husband) and then to his cousin, the duke of Savoy, both of them allies who had led large armies for Spain in the 1550s. But both turned him down. At the same time, Alba’s gout abated. Accordingly, on November 29, the duke accepted command of the army to subdue the Low Countries. By then, however, snow had closed the Alpine passes. Although the Spaniards from Sicily, Naples, and Sardinia reached Milan in mid-December, they could no longer cross Mont Cenis in safety. They therefore wintered in Milan, while Alba wintered in Spain.

Preparations for the expedition nevertheless continued relentlessly. In Spain, the treasury earmarked nearly one million ducats for the duke’s march and recruiting agents assembled troops to replace the veterans. In Italy the newly appointed commissary general of Alba’s army, Francisco de Ibarra, sent an engineer and three hundred pioneers to build esplanadas (widened tracks) in the steep valley leading up from Novalesa through Ferreira to the Mont Cenis Pass. Ibarra also began to assemble provisions and equipment for the troops. Finally, on April 17, the king met with Alba in his palace at Aranjuez to finalize arrangements, and promised that he would sail directly from Spain to the Netherlands and take over as soon as it was safe to do so. Ten days later the duke set sail for Italy, accompanied by almost 8,000 new recruits to replace the veterans he would lead to the Netherlands.

IN EARLY JUNE, Alba reached Milan, where he found 1,200 Spanish and Italian light cavalry and 8,652 veteran Spanish infantrymen. He made only one important change to their organization: The duke equipped 15 men in each company with muskets—smoothbore, muzzle-loading firearms about four feet long (and therefore needing forked rests to steady them), weighing about 15 pounds, and firing a two-ounce lead ball. At the time, muskets were relatively new. Spanish garrisons in North Africa had used them for skirmishing since the 1550s, but Alba was the first to deploy them as a field weapon. Their number soon increased: A muster of the same Spanish regiments in the Netherlands in 1571 showed 600 musketeers—more than 10 percent of the total—with almost one-quarter more equipped with the lighter arquebus.

Still Alba hesitated. The Mont Cenis Pass remained deep in snow, and in any case he feared to lead his veterans out of Italy before knowing that the Turks would not launch another attack. But then news arrived from the east that could scarcely have been more reassuring. The death of Sultan Suleiman in Hungary had provoked mutinies in the Ottoman army and revolts in some outlying provinces against his successor. Clearly the Mediterranean would be safe from Turkish aggression for some time to come. On June 15, 1567, the duke led his men out of Milan. The first contingents marched through the Mont Cenis Pass six days later.

Commissary General Ibarra had almost 10,000 troops to feed, a serious logistical challenge in itself, but one made much worse because most men traveled with servants or family members. Ibarra therefore had to cater for 16,000 “mouths” and 3,000 horses as the army passed along its route. Negotiating the Mont Cenis Pass proved particularly challenging. One of the Spaniards recalled:

Four and a half long leagues of very bad road, because there are two and a half leagues ascent to the top of the mountain—a narrow and very stony road—and after reaching the top we marched another league along a ridge of the mountain, and on this level space there are four huts in which the post-horses are kept. After crossing the top of the mountain there is a very bad descent, which lasts another league, the same kind of road as the ascent, and it leads down to Lanslebourg at the foot of the mountain on the other side, and there the army was billeted. It is a miserable hamlet with a hundred small houses. While we crossed the mountain it snowed and the weather was awful.

The army nevertheless survived this ordeal—even Alba’s gouty legs were unaffected—and on June 29, clear of the Alps at last, the troops arrived outside Chambéry, the capital of Savoy, where they rested for three days.

Although no major physical obstacle now lay between him and the Netherlands, the duke could take no risks. He first had to deal with Geneva, the capital of Calvinism. As soon as they heard news of Alba’s approach, Geneva’s magistrates resolved to increase the garrison and augment food reserves “while the enemy is passing through this land” (thus branding the first users of the Spanish Road as “the enemy”). They also resolved to levy new troops from friendly states and to raise a large loan to pay for them.

The magistrates may also have authorized a more controversial step. Rumors circulated over the winter of 15661–1567 that enemies of Spain armed “with ointments to spread the plague” had entered areas through which Alba and his troops would pass. Cardinal Granvelle, who heard and believed those rumors, concluded that such determined and precocious protagonists of biological warfare must have come from that seminary of revolution and heresy, Geneva. The outbreak of plague in other parts of the region at that time added plausibility to the story, and the Spaniards would later have to change their itinerary in order to avoid towns already infected. No evidence, however, survives of a plan to deliberately spread infection (whether by Calvinists or any other enemies of Spain). There is, by contrast, plenty of evidence that many Catholics considered capturing Geneva. The papal nuncio in Spain begged Philip II to agree, but he replied firmly that “this was not the time to involve myself in other things.” Although the city seems to have remained unaware of this threat, it only demobilized its emergency forces after news arrived that Alba had reached the Netherlands.

Even after the army reached the safety of Franche-Comté, Philip’s own possession, Alba could not discount the possibility of an ambush, either by the rebels or by their Protestant allies, and so his troops regrouped into a single column for the rest of the journey. Scouting parties went ahead to reconnoiter the road and make sure all was safe, but apart from a fire in the camp on July 16 that destroyed some baggage, they found no cause for alarm. The biggest headache remained finding sufficient food each day for 16,000 people—a throng larger than almost any community along the route—as they moved northward. Don Fernando de Lannoy, brother-in-law of Cardinal Granvelle, did his best to smooth the way, either paying cash or setting the goods supplied—food, fodder, transport for the baggage, lodgings for the officers (the rank and file now had to sleep in the open)—against each community’s tax liability. His accounts covered 411 closely written folios. Thanks to Lannoy’s efficiency, and thanks to a special map of Franche-Comté that he prepared to help with navigation, the army made good time.

Meanwhile in Paris, the Spanish ambassador passed a difficult hour convincing French King Charles IX that Alba’s march did not mark the prelude to a surprise attack on France. Charles nevertheless rushed troops into the marquisate of Saluzzo, a French enclave in the Alps; hired 6,000 Swiss mercenaries to shadow Alba’s progress; and increased the garrisons of Lyon and other frontier posts. On the other side of the Spanish Road, the lords of Bern (the largest Swiss canton, staunchly Protestant) likewise raised troops, while the independent city of Strasbourg increased its garrison by 4,000 men.

Apparently unaware of these developments, on July 24, the eve of St. James’ Day, the army reached the little town of Ville-sur-Illon in Lorraine, and the duke and all the other Knights of Santiago (St. James) with the expedition donned the cloaks and hoods of their order and went to the local chapel to hear vespers sung by the army’s chaplains. At midnight and again on the following day (the Feast of St. James, Spain’s national day), the whole army fired a salvo in honor of el Señor Santiago.

The duke now had to deal with a challenge of a different sort. Despite the fact that at the height of the Iconoclastic Fury the previous year Margaret had pleaded with the king to send troops, she now bitterly opposed Alba’s advance and bombarded both Philip and the duke with requests to halt the march. She argued that her own forces, raised with the money sent from Spain, had defeated most of the rebels, while the rest, including the prince of Orange, had fled. The duke brusquely dismissed this suggestion by quoting Margaret’s own words back to her:

I fail to understand how any person of sound mind can be of the opinion that His Majesty should come here with only the mediocre forces at present mobilized. If any moves were made against him from outside or inside the country (where His Majesty has been told that there are more than 200,000 heretics), he would run the dangers and the risks that one can easily imagine.

The duke therefore pressed on, although he did agree that it was no longer necessary to assemble 60,000 other troops to meet him in Luxembourg.

A French observer who saw Alba’s army on the march at this time compared the ordinary soldiers to captains, so impressive were their clothes and their gilded and engraved breastplates, and the musketeers he likened to princes. On August 3, Alba and his refulgent troops crossed the border into the Netherlands. There they halted for a few days, both to recover from their 700-mile march and to ascertain whether it was safe to proceed farther. Rested and reassured, on August 22 the duke rode into Brussels, just four months after he had taken leave of the king in Spain. After all the hesitation and delays, the duke had made good time—and he had lost scarcely any men since leaving Italy, a fact duly praised in contemporary descriptions of his odyssey.

A FEW DAYS BEFORE, however, Alba had received a rude shock. A letter from the king arrived announcing that, despite his solemn promise at Aranjuez, Philip would not be leaving Spain to take control of the Netherlands. It is probably the most remarkable document that the king ever wrote. The first page, filled with his normal spidery scrawl, seems routine, but the seven subsequent pages include material that the king ciphered in his own hand. Yes, Philip II, ruler of the largest state in the world, toiled for several hours at his desk using a codebook borrowed from the clerks of his state department, personally encrypting parts of his message in order to ensure complete confidentiality. “This letter is sent to you in such secrecy,” he told the duke, “that no one in the whole world will ever find out.”

What could possibly justify such circumspection? What plans did the king fear to confide to his own ministers and cipher clerks toiling in their adjacent offices? Fortunately for us, although no draft or copy of the document survives in the state archives, the duke of Alba lacked either the skill or (more likely) the patience to decode the message himself. He therefore handed the royal letter to one of his clerks, who prepared a fair copy of the ciphered pages.

First, Philip explained that it was now too late for him to sail safely to Flanders in the autumn of 1567. Instead, he would do so in the spring of 1568. He next reviewed the consequences of this change of plan for Alba’s mission. Above all, how and when should those involved in the previous disorders be punished? The king had originally instructed Alba to round up all those designated for punishment before he arrived. Now he wrote, “I do not know if you can do this with the necessary authority and justification; but I believe that in the course of this winter you will possess more of both with regard to Germany, which is where any obstacle or complication in this matter of punishment is most likely to arise.” So it would be wise to wait, Philip argued, before carrying out any arrests—especially since a delay might “lead the prince of Orange to feel secure and want to return to those provinces.” Then “you would be able to deal with him as he deserves.” By contrast, “if you punish the others first, it will make it impossible to deal with [Orange] forever.”

Events would vindicate the king’s insight, but unfortunately for his plans, immediately thereafter he made a crucial concession to Alba: “I remit all this to you, as the person who will be handling the enterprise and will have a better understanding of the obstacles or advantages that may prevail, and of whether it is better to move quickly or slowly in this matter of punishment, on which everything depends.”

Next, the king turned to the problem of who would govern the Netherlands until he arrived the following spring. He had dispatched Alba from Spain with full powers to command the royal army but ordered him to share civil authority with Margaret of Parma. Her subsequent hostility to the duke’s march suggested that she would not be prepared to stay on, and in any case some of Alba’s decisions immediately after his arrival made her position untenable. First, he proposed to garrison his troops close to the capital, remaining deaf to Margaret’s complaint that it was unfair to billet them in towns like Brussels, which had remained loyal, instead of in others that had rebelled. She cited reports that, from the moment they entered the Netherlands, the Spaniards had behaved “as if they were in enemy territory”: They jeered the count of Egmont when he came to pay his respects to Alba, they beat up and robbed local merchants as they marched from Luxembourg to Brussels, and they “said that everyone is a heretic, that they have wealth and ought to lose it.”

Nevertheless, the duke once more dismissed her protests, insisting that Philip wanted the Spaniards to remain together so that they could unite rapidly to protect him the moment he arrived in the Netherlands. He therefore summarily dispatched the veterans to their scheduled quarters. The 19 companies of the Naples regiment, for example, entered Ghent on August 30, marching into the city in ranks of five, followed by a large number of prostitutes decked in flounced Spanish dresses and perched on small nags. A horde of camp followers brought up the rear, with bare feet and bare heads, escorting the regiment’s horses, carts, and baggage. After performing a few maneuvers in the city square and firing a salvo to intimidate the natives, the Spaniards descended on the unfortunate householders designated to lodge and feed them.

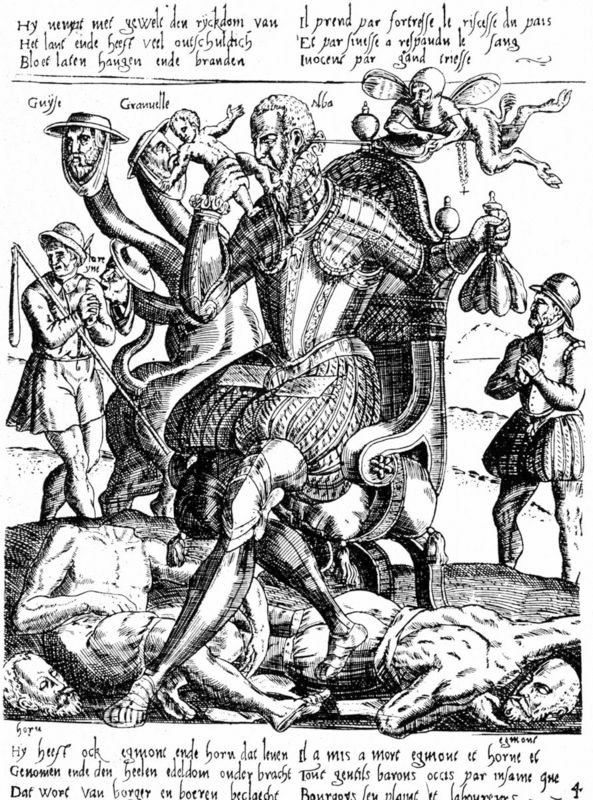

A few days later, without warning Margaret, Alba also disregarded his master’s sage advice and arrested Lamoral of Egmont and other prominent critics of royal policy, accusing them of treason. He also created a special court (popularly known as “the Council of Blood”) to try them. It would eventually judge some 12,000 people, condemn more than 9,000 of them, and execute more than 1,000. “If the Netherlanders see me display a little mildness, they will commit a thousand outrages and difficulties,” Alba told the king. “These people,” he added contemptuously, “are better managed through severity than by any other means.” More arrests soon followed. Embarrassed and disgusted, Margaret resigned and left Alba in sole charge of affairs.

This development, as Philip had feared, led the prince of Orange to remain in Germany, where he raised an army and launched an invasion of the Netherlands the following year. Although Alba mobilized an army of 70,000 men that routed the invaders, the campaign prevented the king from returning to Brussels. The cost of financing these operations and of maintaining the 10,000 Spaniards retained as a permanent garrison forced Alba to impose unpopular new taxes. That fueled far more widespread opposition throughout the Netherlands, so that in 1572, when Orange invaded again, a general revolt broke out that Alba could not crush. Instead, a war began that lasted nearly 80 years, ruined many parts of the Netherlands, drained the resources of Spain, and began its decline as a great power.

In the process of trying to suppress the Dutch Revolt, more than 100,000 troops followed Alba’s itinerary, marching from Italy across the Alps through Franche-Comté to Luxembourg and Brussels. The challenge of organizing such logistical feats year after year gave rise to a Spanish proverb still current: Poner una pica en Flandes (literally, “To get a pikeman to the Netherlands”), which means to do the impossible. It serves as a permanent tribute to the march of the duke of Alba and his 10,000 veterans along the Spanish Road in the summer of 1567. It is a tribute that they would have hated.