Hundreds of American fliers ended up stranded in Siberia—creating a conundrum for the Soviets, who were not at war with nearby Japan.

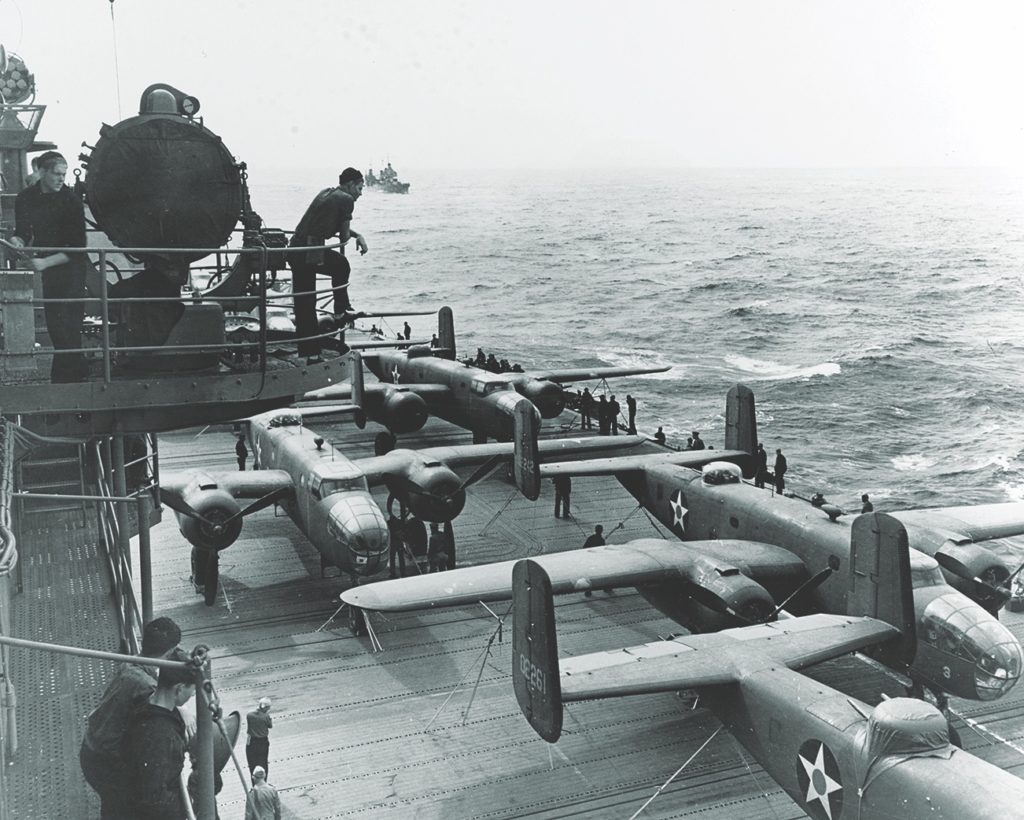

CAPTAIN ED YORK watched the fuel gauges nervously. His bomber hadn’t even reached the Japanese coast before he’d had to switch from the depleted auxiliary fuel tanks to the main tanks. He was burning gas too fast and knew he wouldn’t make it to friendly Chinese territory. It was April 18, 1942, and York’s B-25 was one of the 16 bombers on the Doolittle Raid—America’s first blow against Japan, four months after Pearl Harbor. After his bomb run against a factory near Tokyo, York turned north toward the allied Soviet Union—even though he knew Moscow had denied the United States’ request to use its territory in operations against Japan.

Soviet air defense mistook the B-25 for a similar-looking Soviet Yak-4 bomber. York bypassed Vladivostok and landed at a naval air base 40 miles north of the city. The astonished Soviets greeted the five Americans warmly. Vodka flowed. The base commander asked if they had been part of the Tokyo raid. “I admitted that we had been,” said York, and if he could get some gasoline, “we would take off early the next morning and proceed to China.” To York’s delight, the commander agreed. However, someone up the Soviet chain of command said, “Nyet.”

According to international law, when a combatant enters a neutral country, he is to be interned throughout the duration of hostilities. Although America and Russia were allies in the war against Germany, Russia and Japan were at peace, both upholding their April 1941 Neutrality Pact. When York’s B-25 landed, the Red Army was in a life-or-death struggle against Germany, with the outcome in doubt. Meanwhile, Japan was racking up victory after victory in Asia. Moscow dared not antagonize Tokyo by breaching international law and releasing the fliers, who could again attack Japan. On the other hand, U.S. Lend-Lease aid to Russia was vital, and Stalin was desperate for the Americans to open a second front against Hitler. Washington wanted its airmen back. What was Moscow to do? The solution was an ingenious covert scheme that operated throughout the war and remained classified for years afterward.

THE SOVIET FOREIGN MINISTRY made a formal protest to U.S. Ambassador Admiral William Standley and announced publicly that the Americans would be interned. Tokyo got the message: Moscow would follow international law and honor their neutrality pact. Privately, Joseph Stalin assured Ambassador Standley that the airmen were in good condition and would be treated well. Japanese archives reveal that Tokyo closely monitored the situation. It took Soviet authorities a year to devise a plan that would placate their American allies without risking a crisis with Japan.

The Americans traveled by train across Eurasia to a village 300 miles southeast of Moscow, accompanied by an English-speaking escort, Lieutenant Mikhail (“Mike”) Schmaring. They were housed in a large, relatively clean, walled compound. Conditions were decent, and a housekeeping staff took care of all chores. The Americans played volleyball and watched Soviet movies. Some studied Russian and learned chess. “Mike,” their constant companion, translated war reports from Pravda, from which they gleaned that the Red Army was retreating. In August, they began hearing Soviet antiaircraft fire. The fighting was getting closer.

The German offensive that would die in the rubble of Stalingrad that winter led to the internees being moved eastward to the foothills of the Ural Mountains. Their log house had a kitchen, a dining room, four small bedrooms, wood-burning stoves, and a toilet—an “indoor outhouse” with a hole in the floor. This would be their home for the next seven months. Mike remained their daily supervisor and interpreter. Four local women were recruited for housekeeping and cooking, but conditions began deteriorating. October 7 brought the first snowfall; soon, the weather turned bitterly cold. The food supply grew critical in November. The men subsisted mainly on frozen potatoes, barley, black bread, and tea—as did most locals. By mid-December, the daytime temperature was below zero, sometimes dropping to 50 degrees below at night.

York’s despondent crew decided to appeal to the Soviet High Command. In early January 1943, with Mike’s help, they drafted a letter to the Head of the General Staff asking to be released or given meaningful work in a more moderate climate. Mike promised to mail it. Two weeks later he disappeared, his fate unknown. More discouraged than ever, the airmen’s thoughts turned to vague notions of escape. In late March, however, a Red Army major arrived with the surprising news that their letter had achieved results. They would be transferred south and given work assignments.

The major accompanied them on a long train journey. York’s four crewmen shared two compartments; York shared a compartment with an English-speaking passenger in civilian dress they called “Kolya,” who befriended the Americans. Kolya had several bottles of vodka, which cemented the friendship. It turned out they were all headed to the city of Ashkhabad in Soviet Central Asia, near the border with Iran. Kolya stayed in touch upon their arrival.

The Americans’ new duties involved maintaining small military training planes at Ashkhabad’s airport. Kolya, housed conveniently nearby, spent most evenings with them. York and the others stressed how eager they were to get home; Kolya listened sympathetically. York believed he was enlisting Kolya’s help to escape, and the Russian seemed ready, willing, and able.

Kolya introduced York to a man he claimed was a smuggler who said that for $250 (almost the exact amount the five Americans had among them), he could get them across the border into Iran, then occupied by British and Soviet troops. Kolya told the Americans they should head for the British consulate in Soviet-occupied Meshed. He helpfully provided a hand-drawn map.

On the evening of May 10, 1943, the Americans climbed into the back of a truck for a 150-mile drive toward Meshed—and freedom. Kolya tearfully saw them off. After a bumpy but uneventful ride, the driver ordered them out near the border. The airmen had to crawl several hundred yards and under barbed wire. Despite a bright moon, border guards took no notice. The truck crossed the border, met the Americans on the other side, and drove them to the outskirts of Meshed. Within hours, the airmen were safely in the British Consulate.

The Brits arranged for York’s crew to be driven surreptitiously through Iran into British India. From there, they flew across the Middle East, North Africa, and the South Atlantic to Miami and, on May 24, 1943—nearly 400 days after bombing Japan—to Washington, D.C. The crew was ordered to treat their time in, and departure from, the Soviet Union as top secret.

Their escape had gone according to plan. But whose plan was it? The fact that York was assigned to a railway compartment with a friendly, English-speaking Kolya—who lived within walking distance of their hut, cultivated their friendship, introduced them to a “smuggler,” and gave them a map for their escape—was too much for mere coincidence in Stalin’s Russia, where consorting with foreigners, not to mention aiding their escape, would ordinarily be suicidal. At the time, the Americans may have taken it all at face value. Within a year, however, it became clear to military insiders that the airmen’s “escape” had been arranged by Soviet authorities, although this was kept secret at the time and for years thereafter. Military historian Otis Hays Jr.’s excellent 1990 book, Home from Siberia, brought some of this to light. Materials released in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union helped reveal the full story.

“Kolya” was Major Vladimir Boyarsky, an NKVD (Soviet secret police) counterintelligence officer. In an interview published in Russia in 2004, Boyarsky stated that in March 1943, “I was urgently summoned to Moscow…and ordered to implement an operation to transport to Iran the crew of an American plane that had made an emergency landing in our country. This was a personal order from Stalin himself. The operation was to be carried out in the strictest secrecy…. The most important thing was for them to believe that they themselves had prepared their escape from the U.S.S.R.”

The local border troops (part of the NKVD) constructed a fake section of the border in a remote area, complete with barbed wire. “We skillfully created the simulation of an illegal border crossing,” recalled Boyarsky. “You should have seen the Americans, in the moonlight, looking around and kneeling in order to crawl under the wire barriers as they fled to freedom.”

Although the charade was very realistic, most of the Americans eventually wised up. Tail gunner David W. Pohl wrote years later, “I now believe that our whole escape was engineered by the General Staff and the NKVD.” Copilot Robert G. Emmens, however, disagreed. “Our escape was too real,” he wrote. “It cost us every cent we had…. [Kolya] kissed each of us when we left him…. He had tears in his eyes.”

Why did Moscow decide to release the Americans after holding them for a year? Perhaps the victory at Stalingrad in February 1943 and Japan’s defeats in the Pacific had reduced Soviet fear of a violent Japanese reaction. Perhaps repeated requests from the U.S. government had some effect. Perhaps the decision was triggered in part by the airmen’s letter to Moscow. Soviet sources claim that York’s wife managed to get through to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who personally interceded with Stalin. In any case, the Americans’ “escape” established a pattern that would be repeated.

IN 1943, U.S. AIR OPERATIONS against Japan intensified. More U.S. aircraft began coming down in the Soviet Far East, adding to Moscow’s problem of interned Americans.

Five days after York’s crew arrived in Washington, U.S. forces recaptured the Aleutian island of Attu, seized by Japan in June 1942. U.S. bombers were soon operating from Attu against enemy bases in the Kuril Islands, the northernmost part of the Japanese homeland. From the northern Kurils one can see the tip of the Soviet Kamchatka Peninsula jutting south from Siberia into the North Pacific like a huge frozen version of Florida.

American pilots recalled Soviet coastal artillery firing safely behind U.S. planes in a “display of neutrality.” Soviet fighters sometimes appeared “to drive off any Japanese fighters that might have followed us.” Still, from August 1943 to July 1945, 32 damaged U.S. bombers carrying 242 crewmen landed or crashed in Kamchatka or ditched at sea nearby. Russian archives reveal that at one point, 34 American fliers were housed in Kamchatka near 17 Japanese seamen rescued from a shipwreck—a delicate problem for Moscow.

The Soviets responded to this influx of American airmen by establishing a permanent internment camp near the village of Vrevsky, 35 miles southwest of Tashkent, the largest city in Soviet Central Asia. Tashkent could provide superior logistical support, there would be no sub-zero weather, and there were road and rail lines leading toward Iran.

The camp at Vrevsky occupied a former school complex with buildings sufficient to house well over 100 internees and a staff of housekeepers, cooks, administrators, guards, and a doctor. The head interpreter, Nona Solodovinova, an attractive woman in her 40s, sympathized with the men’s problems and became known to many of them as “Mama.” The camp was not a prison. There were no fences or walls. The internees could walk into town, shop at the market, and mingle with the local population. But it was neither free nor comfortable. Internees were required to be back in camp each night. A few individual escape attempts ended with the airmen being quickly caught and returned to camp. The camp commandant and the ranking U.S. officers jointly maintained military discipline and order. Food quality and quantity varied, but at best was monotonous and often far worse. Dysentery and bedbugs were pervasive. The men played baseball, volleyball, and chess; they had a piano and were allowed a shortwave radio; they read magazines, studied Russian, and watched Russian movies. They repeatedly asked, in Russian and English, “When are we going home?” The answer: often a vague “skoro” (soon). The men adopted two mongrel dogs. They named one Skoro. The internees knew nothing of the York crew’s “escape” or of any plans for their own repatriation.

In mid-1944, U.S. B-29s began hitting Japan from Chengdu, China. The big new Superfortresses had enough range for the round trip from central China. Their second mission on August 20 met intense Japanese flak. As Major Richard McGlinn banked his B-29, one of his engines was hit. He feathered the prop and headed across the Yellow Sea toward China. But he and his navigator concluded that the plane was too heavily damaged to limp back to Chengdu, so they flew north across Korea toward Vladivostok. In the darkness and heavy weather, they missed Vladivostok and, fearing they had veered west into Japanese-occupied Manchuria, continued north until they were sure they were over Soviet territory. When their crippled plane ran short of fuel, the crew bailed out. In the darkness, 11 men parachuted into the vast wilderness of eastern Siberia. They landed scattered across the sparsely populated and almost impenetrable taiga—swampy forestland between the Siberian steppe and tundra—ill-prepared for the ordeal that awaited them.

Dawn on August 21 found the airmen in three separate groups. Seven landed close enough to each other that they were able to assemble by shouting and firing their sidearms. Led by Lieutenants Almon Conrath, the engineer, and bombardier Eugene Murphy, they followed a stream they hoped would steer them to an inhabited area.

Navigator Lyle Turner and copilot Ernest Caudle landed deep in the forest, apart from the others. They also started following a small stream they hoped would lead to civilization.

Major McGlinn landed on the other side of the mountains. His parachute snagged in a big tree, and he hung 60 feet off the ground, soaked by rain all night. When he finally got to the ground, he started blowing a signal whistle and eventually got a response from his tail gunner, Charles Robson. They united far from the others. Their ordeal would be the longest.

The airmen’s gear included emergency rations, matches, compasses, knives, and small arms, but little ammunition. Their survival training had focused on India and China, not Siberia. Trudging through the dense swampy forest sapped their energy. Their rations soon gave out, and they faced hunger. One recalled, “We ate anything and everything edible, including angleworms.” Had their mission been a few months later instead of August, they would all quickly have died of exposure. As it was, they were doomed to a slow death unless they could get outside help.

One of the airmen in the group of seven had a small map of Siberia. After bushwhacking downstream for days, the exhausted men decided to build a raft. Construction consumed several days and much energy, but their makeshift raft could only carry three men. They decided that the three strongest, Lieutenant Eugene Murphy and Sergeants John Beckley and Melvin Webb, would proceed downstream through the wilderness in an effort to bring help to the others. Two days after this party left, navigator Turner and copilot Caudle miraculously stumbled upon the remaining four men. The six hunkered down together.

After a few days on the water, the three trailblazers found the stream impassible and abandoned their raft. A week of hacking through the taiga had left them half-starved and exhausted when, on September 10, they saw several collapsed buildings on the far side of a midsize river. A man and a boy appeared in a hand-hewn boat and ferried them across the river to a tiny village. The local woodsmen spoke no English but treated the Americans kindly and fed them.

A few years ago, one of the authors, historian Yaroslav Shulatov, came across an unusual archival document: a short but heartfelt letter from a minor official in an obscure village in the forests of the Soviet Far East to Vyacheslav Molotov, Stalin’s foreign minister. This document triggered the authors’ research into this story and led to the discovery of unpublished Soviet documents that provided details of the Americans’ rescue not previously known in the West.

The three airmen had reached the village of Bira on the Anyuy River, 100 miles northeast of Khabarovsk, the administrative center of the Soviet Far East. After two more days on the river, they were brought to the town of Troitskoye, where they met an NKVD Border Guard officer who spoke a little English. The Americans immediately explained that their buddies upstream desperately needed help. Soviet officials saw this as a life-and-death situation. The local party boss, Leonid Volkovich, met with the local NKVD commander, Captain Pavel Kolachev, to coordinate rescue efforts. That same day, the first of several groups of hunters and NKVD border guards set out looking for the Americans. Captain Kolachev personally led a search party that trekked nearly 200 miles through the taiga for two weeks. Meanwhile, Volkovich reached out to higher authorities in Khabarovsk for help, and Soviet Air Force planes joined the search.

After three days at Troitskoye’s rudimentary hospital, the three fliers traveled via motorboat to the military hospital in Khabarovsk. That same day, a Soviet pilot sighted a signal mirror flashing in the forest. The six U.S. airmen on the ground were overjoyed when the plane circled and signaled it had seen them. The next day, the plane returned and dropped food and a message in English: “Be patient, help is on the way, your three comrades are safe.”

It took four days for the rescuers to reach them, forcing their way upstream against a strong current, logjams, and debris. In another four days, the woodsmen and border guards transported the six Americans by boat and horseback to Troitskoye, where they received the same kind treatment as their three comrades. Lieutenant Turner later recalled that the Soviets “gave us everything they had, and even more—the nurses even brought us food from their own homes.” The Americans also got another piece of wonderful news: Soviet fliers had discovered two men up north. It had to be McGlinn and Robson.

McGlinn and his tail gunner had landed in a particularly remote area and began trekking northward, but this led them deeper into the wilderness. For weeks they struggled against the nearly impenetrable forest, tortured by clouds of gnats day and night, weakened by chronic hunger, and disheartened by the total absence of any sign of human presence. Mc-Glinn recalled, “Anything that we could catch, whether it crawled or flew, was food.” They were losing nearly a pound a day and were in desperate shape.

Soviet Air Force planes were flying long-range searches. On September 22, 32 days after the Americans blundered into the taiga, smoke from a fire they had kindled caught a Soviet pilot’s eye. He banked closer and saw the flash of a signal mirror. The next day, the plane returned and dropped food and a message: “You are in Soviet territory and Soviet pilots are at your service.” McGlinn and Robson attacked the food and ate for hours. Three days later, the plane brought more food and instructions: “Stay where you are. A rescue party will arrive soon.”

The rescue party, led by an engineer working on a railroad construction project, arrived two days later and brought McGlinn and Robson by boat to the village of Tolomo. (The railroad was a strategic project managed by the NKVD. Ironically, the NKVD—the principal instrument of Stalin’s terror—played a positive role throughout this saga.)

McGlinn later wrote, “The treatment received at their hands…could be likened only to the loving care that any close relative would receive from one of their kin.” Two more days of river travel brought the exhausted airmen to the military hospital in Komsomolsk, some 240 miles northeast of Khabarovsk—40 days after their plane went down. In November 1944, they traveled by train to the camp at Vrevsky, where they joined nearly 100 other interned American airmen.

None of these Americans knew that the previous February, a group of 60 U.S. internees, told they were being moved to the Caucasus, had been smoothly transported by train and truck to Tehran, Iran. Their transfer to the trucks was masked by a pretend mechanical breakdown on one of the railroad cars. It was only then that the airmen learned their true destination. This charade was orchestrated flawlessly by the NKVD. The internees were accompanied by Colonel Robert McCabe from the U.S. Embassy, an NKVD officer, and a Red Army staff officer. From Tehran, the airmen followed a circuitous route back to the U.S. to conceal the fact that they had departed from Russia. Like York’s B-25 crew, they were ordered to treat being interned in and released from the U.S.S.R. as top secret.

When McGlinn’s crew reached the camp at Vrevsky on November 26, 1944, Soviet plans for a third escape to Iran were already well advanced, although the Americans knew nothing of it. The intent was to duplicate the scenario employed the previous February. On November 30, the same NKVD, Red Army, and U.S. Embassy trio arrived. Colonel McCabe told the assembled internees that they were being transferred to Tbilisi in the Caucasus. They were to leave on December 3. “Mama” Nona, who had been in the camp in February, confided to the ranking U.S. officer, “You’re not going to the Caucasus, you’re going home!” But events back home fouled up the plan.

Just before departure, two stories appeared in American newspapers from unknown sources about the Doolittle crew’s release from Soviet internment. The second account was detailed and accurate. When authorities in Moscow learned of these leaks, they halted the operation. By then, the train carrying 100 American airmen was nearing the Iranian border. It pulled onto a siding, and a grim-faced Colonel McCabe told the men that they were going back to Vrevsky. Over the next few hours, separate groups of internees—34 men in all—more or less spontaneously began walking away from the railcars in hopes of reaching the border. None got very far, and they were rounded up by alerted Soviet sentries. By December 13, all 100 men were back in camp. Remarkably, there was no Soviet punishment for the attempted escape.

On January 2, 1945, President Roosevelt assured Moscow that he had ordered strict censorship of any news stories regarding the release of internees from neutral countries. Six days later, the NKVD informed the U.S. Embassy that the “escape” plan could resume.

The internees—this time briefed on the plan in advance—boarded a train on January 26, and two days later transferred to a convoy of Lend-Lease trucks for the two-day drive to Tehran. Greeted by U.S. medical corpsmen, they were deloused, issued fresh clothes, and treated to an American meal. McGlinn recalled that the simple white bread and butter “tasted like angel cake.” Finally, they collapsed in “beautiful, clean, white beds.” The men flew, with many layovers, from Tehran to Naples, Italy, where they boarded a U.S. transport ship that brought them to New York City. They were required to sign pledges swearing them to secrecy about being interned “in a neutral country.” Most men respected the pledges.

Even before this third escape was launched, more American bomber crews were making emergency landings or crashing in Kamchatka. On February 5, 1945, just a week after the 100 internees had left Vrevsky, a fresh batch began arriving. They found ample evidence of the earlier American occupants, but the Russian staff kept mum about what had become of them. By mid-May, there were 43 internees at Vrevsky. Germany had surrendered a week earlier, and the Red Army was secretly preparing to enter the war against Japan. Japan was being crushed by American might, and Moscow was no longer worried about what Tokyo might do in response to the release of American internees. On May 18, Colonel McCabe’s replacement and two Soviet officers flew to Vrevsky to supervise the final “escape.” It followed the same scenario and route as in February, without much drama or a make-believe railcar breakdown. Because of the small number of evacuees and the end of hostilities in Europe, the men flew from Tehran to Washington in four days. Like their predecessors, they were sworn to secrecy.

Over the years, some of the Americans continued to regard their internment bitterly, feeling that they had been treated like POWs. Many more, however, concluded that they were treated as well as could be expected under the extreme conditions in the Soviet Union, which was fighting for survival, suffered 27 million war dead, and had to avoid the risk of a second front against Japan at all costs. “We were treated far better than the average Red Army officer,” Major McGlinn concluded—an opinion shared by many others.

In the fall of 1945, Leonid Volkovich, the man who had helped rescue McGlinn’s crew the previous year, sent the official letter mentioned earlier to Vyacheslav Molotov. Why did an obscure party official from Troitskoye appeal directly to the number-two man in the Soviet hierarchy, over the heads of his innumerable superiors? Volkovich believed he was calling attention to an issue of national importance—the operation that had saved the lives of 11 Americans. Apparently hoping to be recognized and rewarded for his work, Volkovich described the ground and air maneuvers in detail, emphasizing that the “heroic” efforts made to locate and aid the Americans had honored the Soviets’ duty to their U.S. allies. Brimming with emotion, he stressed the successful rescue’s magnitude and value: “We…allowed the airmen to return home and tell their fellow Americans how a large number of ordinary Soviet people, running themselves ragged at great cost and at risk to themselves, rescued them from the arms of certain death…and returned them to the ranks of the United States Army.”

But by late 1945, frigid Cold War winds were already blowing through government offices in Moscow and Washington, chilling the fragile wartime friendship. The Soviet leadership had no sympathy for Volkovich’s glorification of Soviet-U.S. cooperation. The authors could find no reply from Molotov in the archives. ✯

This article was published in the April 2021 issue of World War II.