When astronauts experience technical difficulties in the vastness of outer space, they radio mission control for help. Witness Apollo 13 commander Jim Lovell’s oft-misquoted 1970 plea, “Houston, we’ve had a problem.” By contrast, men in the Age of Sail who crossed vast oceans in wooden ships lived in utter isolation. While at sea they had no communication with the outside world aside from chance encounters with friendly ships. When trust broke down among such men, the threat of catastrophe loomed. Consider the 1842 Somers affair.

By all accounts U.S. Navy Midshipman Philip Spencer was a daydreaming, hard-drinking nuisance from a distinguished family. His father, John Canfield Spencer, was New York’s secretary of state in the spring of 1841 when teenage Philip bolted from Schenectady’s Union College to sign on to a Nantucket whaler. His father caught him before the ship set sail and instead arranged a naval officer’s commission for the boy. If Philip was determined to go to sea, his father reasoned, he would do so as a gentleman. In the ensuing months the elder Spencer was appointed President John Tyler’s secretary of war, while his wayward son drank and brawled his way to dismissal from three successive shipboard assignments. Philip avoided courts-martial due to his father’s standing, and he was fortunate to obtain a post aboard the brig USS Somers.

Or perhaps not so fortunate, as that assignment put Spencer on a collision course with Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, the ship’s captain, who on Dec. 1, 1842, executed the young man as the ringleader of a plot to commit mutiny. A naval historian and best-selling author, Mackenzie enjoyed a reputation in his native New York as a genial military celebrity. When commanding a ship, however, he used harsh methods to enforce strict discipline. His decision to hang Spencer and two others without trial sparked the biggest American military controversy in the decades before the Civil War and helped prompt the 1845 founding of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md.

The Navy saw the outcome as fair punishment for three bad apples who tried to spoil others. Members of the public, however, decried it as tyrannical act by a paranoid captain and a lesson in the pitfalls of rushed judgment.

Trouble erupted during the return passage across the mid-Atlantic. It had been brewing since before Somers left Brooklyn

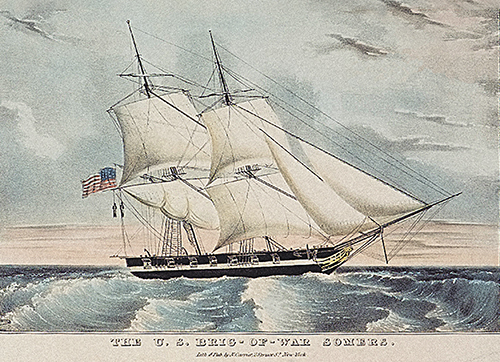

Launched in April 1842, the 10-gun Somers measured 100 feet long and displaced 259 tons. The compact ship was packed with men and supplies when it sailed from the Brooklyn Navy Yard that September 13 on its maiden transatlantic voyage. Somers was tasked with a twofold mission. First, it would deliver dispatches to USS Vandalia, an 18-gun sloop of war expected to be on station off the West African coast. Somers would also act as an experimental school ship. Most of its 120 crewmen were apprentices, both enlisted and officer recruits, who would learn on the job—a new twist on the old practice of training recruits aboard active warships. (Officer cadets were called “midshipmen,” a term still in use, as they berthed and/or worked amidships.) Navy brass thought grouping such students aboard one warship would prove more efficient than distributing them throughout the fleet.

Somers arrived off Monrovia, Liberia, on November 10 only to learn Vandalia had already departed for the United States. After delivering the dispatches to a local American agent, the brig sailed the next day, shaping a westward course for St. Thomas, in the Danish West Indies (present-day U.S. Virgin Islands), where Mackenzie intended to resupply before returning to New York.

Trouble erupted during the return passage across the mid-Atlantic. It had been brewing since before Somers left Brooklyn. In his official report of the voyage Mackenzie recalled having met Spencer around August 20 as the crew prepared to get the ship underway. The midshipman had just been dismissed from a stint with the U.S. Navy’s Brazil Squadron for drunkenness and disgraceful conduct. Mackenzie wanted none of that aboard his ship, particularly since he’d been personally entrusted with the welfare of four embarking sailors, two related to him.

That Spencer had a politically connected father only made Mackenzie more eager to be rid of him. “I have no respect for the base son of an honored father,” he wrote. “On the contrary, I consider that he who by misconduct sullies the luster of an honorable name is more culpable than the unfriended individual whose disgrace falls only on himself.” The commander wanted Spencer transferred but was denied permission. So he cautioned his officers and midshipmen to avoid Spencer, who in turn broke Navy regulations by seeking friends among the enlisted men, bribing them with tobacco, money and other gifts.

Tasked with leading a green crew of seasick, homesick boys, Mackenzie often ordered whippings, afterward making grandiose speeches about honor and self-control. Regardless, in retrospect many crewmen were of the opinion the brig suffered a relative lack of discipline. For example, though several men openly cursed the captain and threatened to throw him overboard, officers within hearing failed to report such transgressions to Mackenzie.

On November 26 1st Lt. Guert Gansevoort, Mackenzie’s second-in-command, did report a problem to the captain, sharing a disturbing tale from Purser’s Steward James W. Wales. According to the latter, the previous night Spencer had asked Wales to climb up to the booms, a collection of spare spars suspended above the deck amidships, where they could whisper without being overheard. After swearing Wales to secrecy, Spencer said he and some 20 others planned to seize the ship, kill all the officers—as well as any enlisted men unwilling to join them—and plunder the Caribbean as pirates. While they spoke, Spencer beckoned over Seaman Elisha Small, who spoke briefly with the mutinous midshipman in Spanish, which Wales didn’t understand. Before leaving, Small said in English he was pleased Wales had joined them. Why the steward had waited till daylight to report the incipient uprising is unclear.

Mackenzie ordered Gansevoort to shadow Spencer that day and report any suspicious behaviors. According to the first lieutenant, Spencer scanned a chart of the West Indies in the wardroom and asked the ship’s doctor about the Isle of Pines, a notorious pirate haunt. He also climbed into the rigging to get a tattoo from a seaman apprentice, another violation of the Navy’s line between officers and the enlisted. Word had it Spencer was trying to ascertain the rate of the ship’s chronometer, had once scribbled a picture of a brig with a black flag and had met secretly with Seaman Small and Boatswain’s Mate Samuel Cromwell, both experienced mariners. Was Spencer merely seeking to learn celestial navigation from those with the know-how, as some later suggested, or was he plotting insurrection?

At evening quarters Mackenzie questioned Spencer about the conversation he’d had with Wales the previous night. The midshipman admitted to having spoken mutiny, but in jest. “This, sir, is joking on a forbidden subject,” Mackenzie fired back. “This joke may cost you your life.” At that he had Spencer’s sword confiscated and clapped him in double irons. Even if Spencer had been joking, Mackenzie was justified in his response: Government officials are not permitted to joke about certain topics. An officer cadet whispering about mutiny at sea was like someone yelling “Fire!” in a crowded theater. The statement itself could cause harm, whether intentional or not. When a cryptic document with apparent plans for mutiny was discovered in Spencer’s personal sea chest, Mackenzie and his officers were compelled to act.

An officer cadet whispering about mutiny at sea was like someone yelling ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater. The statement itself could cause harm, whether intentional or not

Known as the “Greek paper,” the document found in Spencer’s possession comprised a list of names written in Greek characters, which Midshipman Henry Rodgers was able to translate. The top four names were marked “certain” and included P. Spencer, E. Andrews, D. McKinley and Wales. Ten more were listed as “doubtful,” with a further 18 grouped under “nolens volens” (to be kept, willing or unwilling). The paper also noted apparent post-mutiny postings: McKee at the wheel, McKinley at the arms chest and so on. While the document made no mention of mutiny, murder or other crimes, it did read in part, “The remainder of the doubtful will probably join when the thing is done; if not, they must be forced. If any not marked down wish to join after the thing is done, we will pick out the best and dispose of the rest.”

As evidence of a conspiracy, however, the document had several problems. For starters, nobody named “E. Andrews” was aboard Somers. Cromwell, a leading suspect, was not listed, while Wales—the man who had brought the story to his superiors’ attention—was listed as a “certain” conspirator. Yet the situation had to be taken seriously. Mutiny was a contagion that if left unchecked could infect the whole crew. At the time Somers was arguably the fastest vessel in the Navy, a potent quick-strike weapon that could become a fearsome pirate ship in the wrong hands. That night the officers on watch armed themselves with cutlasses and pistols and performed extra inspections to ensure crewmen were in their hammocks.

The next morning, at Sunday services, Mackenzie scrutinized his men’s faces for any sign of guilt. Winds lightened that afternoon, and the captain ordered crewmen aloft to set the topmost sails. Just after the main skysail luffed into place, the main topgallant mast—sails, rigging and all—came crashing down on the deck. Used only in light winds, this topmost rigging was inherently weak and susceptible to collapse in changeable winds, a relatively common occurrence. Yet Mackenzie blamed its collapse on the deliberate “sudden jerk” of a brace line by Small and another sailor. He explained his thinking in his report. “I knew it was an occasion of this sort—the loss of a boy overboard or an accident to a spar, creating confusion and interrupting the regularity of duty—which was likely to be taken advantage of by the conspirators,” he wrote. In his state of heightened alert every incident was tied to the mutiny.

The crew, including Cromwell, rushed to help. They coiled the rigging, bent the sails to the yards, pulled out the spare topgallant mast and prepared to fit it in place. Amid the activity, however, Mackenzie was alarmed to see virtually every suspected conspirator clustered together about the main topmast, though several should have been on duty elsewhere.

Where the captain again perceived conspiracy, however, his critics saw good seamanship. As acting boatswain’s mate and one of the strongest men aboard, Cromwell had a duty to jump into the rigging and help fix the mess, especially on a cruise with a crew of boys who had probably never seen a mast section replaced in an emergency. For his part, Small went up into the rigging as captain of the maintop, among his duties.

Night had fallen by the time repairs were complete. Worried about what might happen under cover of darkness, Mackenzie questioned Cromwell about conversations he’d had with Spencer. Cromwell denied any wrongdoing but implicated Small, so the captain had both men put in irons and further interrogated. While arresting Cromwell, Gansevoort accidentally discharged his pistol—the only shot fired during the six-day affair.

Ordering all his officers to arm themselves, Mackenzie preached vigilance. When the captain confiscated Spencer’s daily ration of tobacco and the latter reacted sullenly, Mackenzie took it as a further sign of guilt, rather than simple addiction.

Mackenzie had Wardroom Steward Henry Waltham flogged on November 28 and 29 for having stolen a bottle of brandy and conspired to steal three bottles of wine. Mackenzie concluded Waltham had wanted the alcohol to fuel insurrection, “his object being, no doubt, to furnish the means of excitement to the conspirators, to induce them to rise…and get possession of the vessel.” A cooler head might have imagined other, more mundane uses for wine.

Truth was becoming entangled in a web of rumor and self-centered motivations. As a purser’s steward, Wales handled such petty duties as weighing tobacco for distribution. Suddenly finding himself one of the captain’s trusted men, he strutted about the deck, imperiously cocking a pistol in shipmates’ faces over real or imaginary transgressions. After initially informing the captain someone had moved to stab him with a marlinespike, he later testified at a subsequent court-martial the sailor in question had merely been retrieving the spike from storage. “What his intentions were, I don’t know,” Wales stated, adding he was 40 feet from the man, thus not in any danger. Unfortunately, Mackenzie would use Wales’ original assertion as justification for the forthcoming executions.

Mutiny, even in the planning stage, was a capital offense at sea and gave a captain wide latitude to do as he saw fit

Mutiny, even in the planning stage, was a capital offense at sea and gave a captain wide latitude to do as he saw fit. With three crewmen on deck in irons, Mackenzie determined he could not safely make port in St. Thomas. He lacked space to safely segregate the prisoners from those they might infect with mutinous intent, and he had only one U.S. Marine aboard to help put down any uprising. Wales further informed the captain he’d seen the prisoners communicating with hand signals. Morale was in free fall. Mackenzie felt compelled to convene a council of officers to debate the prisoners’ guilt.

On November 29 the captain had his officers gather in the wardroom for their council. That same day Mackenzie had four more suspects clapped in irons. Whatever his intention, the arrests drove home the notion of a spreading conspiracy even as his officers met to decide whether there was such a conspiracy. While the sleepless captain stood watch on the quarterdeck, his officers met belowdecks that day and the next, quietly calling witnesses.

Novelist James Fenimore Cooper, himself a former midshipman, wrote a 102-page takedown of Mackenzie after the Somers affair came to light. Like other critics, he floated the idea that the Greek paper may have been a madcap joke, but that Wales saw it spiraling out of control and got himself on the other side to avoid consequences. Cooper deemed Mackenzie a tyrant for having refused to allow the accused to cross-examine witnesses—a breach of basic jurisprudence. Cooper also suggested the council had selected witnesses and altered testimony to fit a preordained outcome. Whether or not that was true, by day’s end on November 30 the council delivered its unanimous opinion: Spencer, Cromwell and Small were “guilty of a full and determined intention to commit a mutiny.”

Mackenzie still had options. At that point Somers was within 250 miles of the Caribbean, experiencing beautiful weather with the trade winds at its back. The brig could make that distance in a day and a half. Cooper argued that rather than executing the accused, Mackenzie could have confined the men belowdecks, making his own cabin into a holding cell, for example. The novelist also noted that in past mutinous circumstances ship captains had safeguarded their command by running a line across the ship, port to starboard, forward of the helm and declaring that no unauthorized crew were permitted aft. Swiveling a couple of deck guns forward would drive home the point.

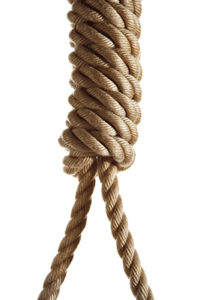

Mackenzie instead determined to mete out justice. Emerging on deck in uniform on Thursday morning, December 1, he ordered three whips sent over the main yardarms. The boatswain’s pipe pierced the air, followed by orders for the crew to assemble and witness punishment. The captain then informed Spencer, Cromwell and Small of their fate, each in turn. It was the first time they’d even learned a council had been convened. Given an opportunity to speak, Spencer sought forgiveness for his role. “As these are the last words I have to say,” he cried out, “I trust they will be believed: Cromwell is innocent!” Shaken with doubt, Mackenzie stopped the execution to poll Somers’ petty officers—men with no knowledge of the council’s proceedings. They affirmed Cromwell’s guilt, regardless.

For maximum disciplinary effect, Mackenzie chose those who had worked closest with the condemned to be their executioners. The afterguard and idlers were entrusted with Spencer’s whip, while Cromwell’s hangmen came from the forecastle and foretop, and Small’s from the maintop. The petty officers—each still armed with a cutlass, pistol and box of cartridges—patrolled the spar deck with instructions to see that every man hauled down on his assigned whip with both hands. They covered the faces of the condemned, while others readied a signal gun. Spencer asked permission to order the execution himself. Minutes passed before word reached Mackenzie the teenager couldn’t go through with it. The captain then calmly passed the order, the gun boomed, and up went the co-conspirators. Afterward Mackenzie gave a speech about “truth, honor and fidelity” and ordered his men to give “three hearty cheers” for the Stars and Stripes. The crew members then went below to eat their evening meal with the three corpses still swinging over the water.

As darkness fell, sailors dressed Spencer in full uniform, minus his sword, and placed the midshipman’s body in a coffin cobbled together from two mess chests. Per tradition, they laid out the bodies of Cromwell and Small in their hammocks and sewed them shut. Next, they lit every lantern on the ship and gathered, many atop the yards and in the rigging, for a solemn burial service. Finally, they committed the bodies to the deep.

Four crewmen remained in irons. On Somers’ arrival in New York on December 15 Mackenzie had an additional eight arrested as conspirators. On hearing the news of the execution, Spencer’s father tried to get the case brought before a civilian court, but even a member of the president’s cabinet was unable to keep the Navy brass from closing ranks around one of their own. They granted Mackenzie both a naval court of inquiry and a court-martial. His defense leaned heavily on the prior testimony by Wales, and the captain of Somers was cleared of any wrongdoing. MH

A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Paul X. Rutz is an artist and freelance writer. For further reading he recommends The Cruise of the Somers: Illustrative of the Despotism of the Quarterdeck and of the Unmanly Conduct of Commander Mackenzie, by James Fenimore Cooper, and Rocks and Shoals: Naval Discipline in the Age of Fighting Sail, by James E. Valle.