It was perhaps the slowest heist in history.

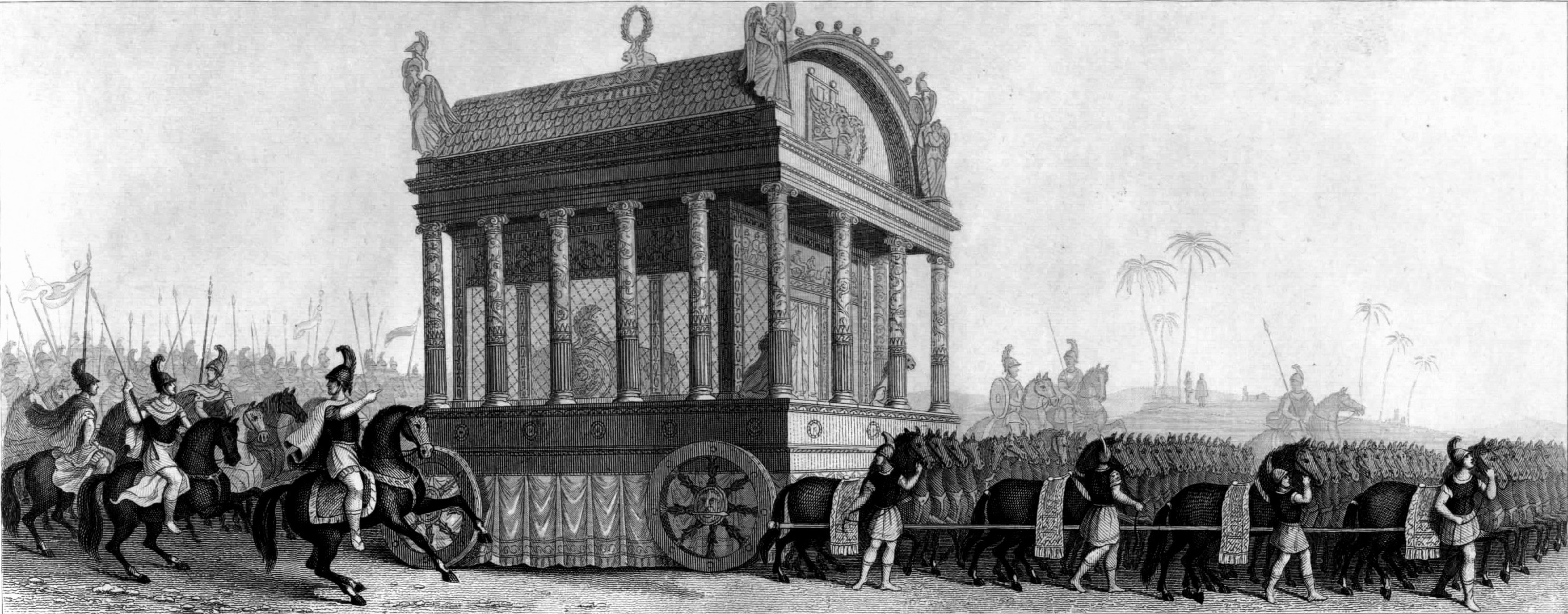

After being held in Babylon for two years, the body of Alexander the Great, entombed in what amounted to a temple on wheels, began its labored procession west for his final burial.

Yet the fight for exactly where that burial would take place had just begun.

The demise of Alexander in 323 B.C. left a power vacuum across his empire. With no successor named, a mad scramble for control of the vast territories ensued.

“His body becomes the heritage of the empire,” historian Tristan Hughes told Dan Snow on the latter’s podcast, History Hit. “Whoever control[ed] possession of Alexander’s body h[eld] great sway in this new post-Alexander world.”

Perdiccas, a general within Alexander’s army and regent of the Macedonian empire after Alexander’s death, sought to cement his own power and ordered for Alexander’s funeral procession to make its way to Central Anatolia, where Perdiccas was then stationed.

Thus, the game was afoot.

Warring factions, namely Perdiccas’ archrival Ptolemy — the governor of Egypt — had no intention of ceding power so easily and hatched the audacious plan of stealing the gold-plated sarcophagus right out from under Perdiccas.

In contact with General Arrhidaeus, the head escort of the funeral carriage, Ptolemy colluded with the general to have the procession turn south towards Memphis, Egypt, once it reached eastern Syria — most likely near modern-day Aleppo.

The body of Alexander the Great had officially been hijacked.

However, what originally aided the kidnappers — the slow-moving funeral procession pulled by 64 mules — also hindered them.

“It was not long before Perdiccas received word of the cart’s new course and sent a special light-armed task force in pursuit,” writes Hughes. “It’s purpose: to retrieve the carriage and its precious cargo — by force if necessary.”

The task force managed to intercept the procession south of Damascus, but Ptolemy had already foreseen this happening and marches with a large, heavily armed force to meet the funeral carriage when it reached the Syrian city to give Alexander the Great’s body the heavily PR’ed spin of giving it the “welcome it was worthy of.”

Perdiccas’ smaller army, unable to force the carriage to go back north, eventually returned to the general corpse-less.

Alexander’s body was ultimately interred in Memphis, yet the battle for the body had just begun — sparking the First War of Successors.