A daring bondsman turned double agent confounds Cornwallis—and helps the Americans win

The summer of 1781 was crucial for King George III’s military in America and for the colonial forces opposing the British. Earlier that year, in March, General George Washington had ordered Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, to depart Philadelphia and lead Continental forces in Virginia. Lafayette was to help counter a British invasion of the American South, as well as confront the traitor Benedict Arnold and his marauders, then ranging around Virginia. In addition, the French officer was to gather intelligence on British troop strength, positions, and strategies.

That August, upon arriving in Virginia, British General Charles Lord Cornwallis, commander of British forces in the South, sent Arnold and his troops north to New York. Cornwallis then sparred with Lafayette across the Virginia Tidewater in actions at the North and South Anna, Rapidan, and James Rivers. From New York, British commander in chief General Henry Clinton ordered Cornwallis to secure a locale on the Virginia coast with a harbor sufficient to accommodate a fleet of warships that would be reinforcing British ground troops. Cornwallis drew his forces back from Portsmouth to Yorktown to meet the enemy, but American and French forces, always seeming to know his movements, steadily dogged the British general and his troops. By October 1781, the rebels and their French enablers were besieging Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown, where circumstance forced the Briton to surrender.

Unknown to Cornwallis, for months his camp had been harboring a secret agent—and not merely a spy informing the Americans but a double agent who had been feeding Cornwallis disinformation about the colonials. That little-known figure, whom a Time writer described as “arguably, the most important Revolutionary War spy,” was James Armistead, an enslaved African American.

Born into bondage around 1748, James Armistead was the property of William Armistead, a New Kent County, Virginia, farmer. Among other activities during the Revolutionary War, William Armistead sold supplies to the American army. Hearing that slaves who served the rebel cause could apply for their freedom once the war ended—assuming an American victory—James Armistead asked his owner for permission to serve with Lafayette’s Virginia campaign. The planter, who regarded James Armistead as trustworthy and resourceful, assented.

An advocate for equality—long after the Revolution, he would write to Washington, “I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America if I could have conceived that thereby I was founding a land of slavery!”—Lafayette took on the black man as a forager, laborer, and courier. Observing James Armistead’s aptitude, Lafayette offered him far more dangerous work: Posing as a runaway slave, Armistead would present himself at Benedict Arnold’s camp, ostensibly to seek work but on the sly gathering and passing on intelligence about British operations and troop strength. Understanding that if he were found out he would be hanged, James Armistead accepted the job. Suitably clad, the “runaway” trekked to the enemy camp, which was in the Virginia Tidewater. Armistead explained to Arnold’s men he knew the vicinity and would be able to guide them, obtain food, and help in whatever way he could. The British took in the ostensible runaway. Cornwallis, planning to sally against Lafayette, sent Arnold and company north and ensconced himself at Yorktown with 5,000 infantry and 800 cavalrymen. James Armistead joined the British general’s camp at Portsmouth, working overtly as a scout and forager and covertly as a secret rebel agent.

Cornwallis made Armistead an orderly, assigned to wait on the officers’ table—a prime position for eavesdropping as the British general talked strategy, going over maps and planned actions. The illiterate Armistead memorized what he overheard and almost daily whispered that information to a fellow operative who was part of a relay team of spies who sneaked through British lines to pass intelligence to Lafayette. Constantly forewarned, the Frenchman, whose forces numbered only 3,000, was able to avoid confrontations and to monitor and report on the British undetected. James also carried instructions from the marquis to other American operatives behind British lines.

Noting his orderly’s acuity, Cornwallis asked the supposed runaway to spy on the enemy. Armistead said yes, informing his Continental Army contacts, who arranged to supply him with fake intelligence. Armistead, now a double agent, began passing along falsehoods provided by handlers on the rebel side about American strength and movements. He fed Cornwallis a steady stream of disinformation, augmented by touches like a bogus letter, supposedly from Lafayette to another rebel general. The crumpled communique, which James claimed to have found on the road, discussed a large number of troops coming to reinforce Lafayette. Reading this discouraged Cornwallis from attacking the American forces.

As the summer of 1781 was ending, the American army was closing in on Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown. In early September, Cornwallis began receiving legitimate reports from trusted sources that a French fleet would be arriving off the Chesapeake Capes to reinforce the Americans. In addition, Washington and his army, marching out of locations in the mid-Atlantic from New York to Pennsylvania, had arrived at Williamsburg. Writing to Clinton, his supposed rescuer, Cornwallis said he feared he could not hold out. In the September 5-9 Battle of the Chesapeake Capes, which proved to be the decisive battle of the war, Admiral Francois Joseph Paul de Grasse’s fleet held off arriving British ships and chased them from the Chesapeake. By closing off British sea approaches to Yorktown, de Grasse deprived Cornwallis of his needed reinforcements.

In early October, the rebels and their French allies began besieging Yorktown. A French fleet arrived at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, crushing Cornwallis’s hopes of aid from the Royal Navy. His back to the sea, with no way of escape, Cornwallis sent an aide to Washington’s camp seeking terms. On the warm morning of Friday, October 19, 1781, Cornwallis signed two copies of the Articles of Capitulation for return to Washington’s headquarters. Noting the scene of victory, the American general wrote at the end of the articles, “Done in the trenches before York, October 19th, 1781.”

A few days after capitulating, Cornwallis, in a gesture typical of the day, visited Lafayette. Entering the Frenchman’s tent, the British leader saw standing near the Frenchman his former orderly, personal servant, and loyal spy, James Armistead. Although fighting continued sporadically until the 1783 signing of the Treaty of Paris, the Revolutionary War effectively ended at “the trenches before York,” as did James Armistead’s career as an American spy.

Armistead returned to New Kent County to resume life in bondage. He expected to obtain his freedom, but under Virginia law only a special act of the Assembly could free a slave. In autumn 1784, James traveled with William Armistead, now a member of the House of Delegates, to Richmond. In the state capital, James encountered Lafayette, who was about to leave for his homeland.

The French noble gave his former secret agent a letter. “This is to Certify that the Bearer By the Name of James has done Essential Services to me While I had the Honour to Command in this State,” Lafayette wrote. “His intelligences from the Enemy’s Camp were Industriously Collected and More faithfully deliver’d. He properly Acquitted Himself with Some important Commissions I gave Him and Appears to me Entitled to Every Reward his Situation Can Admit of. Done Under my Hand, Richmond November 21st, 1784—Lafayette.”

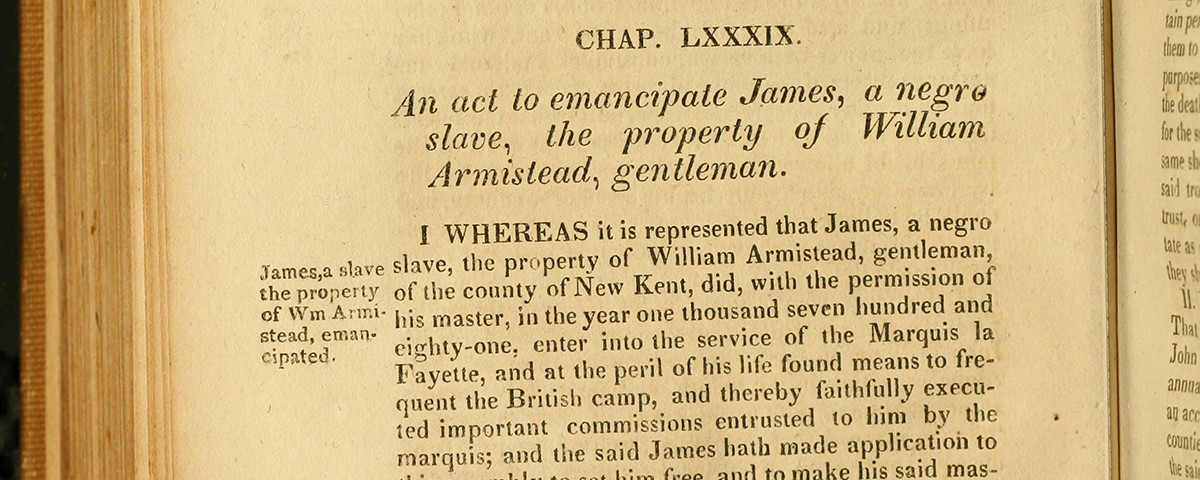

That December, a sickly William Armistead petitioned the General Assembly for James’s freedom, officially known as manumission, from the Latin for “to release control.” Armistead’s petition, inexplicably not sent with Lafayette’s letter of praise, described the enslaved man’s efforts at Yorktown, asking for “that liberty which is so dear to all mankind. . . . [and] praying that an act may pass for his emancipation.” The petition died in committee—the law freeing slaves for serving in the Revolution applied only to soldiers-at-arms, not spies.

In November 1786, William Armistead filed a second, more politically astute petition that included Lafayette’s letter of endorsement. In his own remarks, the planter cited James’s “honest desire to serve this country…during the ravages of Lord Cornwallis thro’ this state,” closing with a plea that the legislature grant James “that Freedom, which he flatters himself he has in some degree contributed to establish.” The petition and Lafayette’s letter were referred to the Committee on Propositions and Grievances, which ordered a bill drafted. The resulting measure unanimously passed the House of Delegates on Christmas 1786, and the Virginia Senate on January 1, 1787. Signed eight days later by Governor Edmund Randolph, the legislation freed James Armistead. Two months later, as compensation for freeing his slave, the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts issued warrants to William Armistead in the sum of £250, far exceeding the usual £100 compensation the state paid for executing a bondsman convicted of a capital crime. In gratitude for the support that the marquis lent to his petition for freedom, James Armistead adopted Lafayette as his last name.

James Armistead Lafayette, freedman, slipped into obscurity, making his living farming. He had a wife and at least one son. The 1787 New Kent County personal property tax book lists Lafayette as owning two horses and three slaves. Black freedmen of that era did sometimes own slaves, but it also was not unusual for property and census recorders to characterize any blacks in a freedman’s household, even family members, as slaves. In 1816, James and family acquired two tracts adjoining William Armistead’s estate, one parcel of 10 acres, the other of 30.

To honor surviving soldiers of the Revolution, in the early 1800s many states and the U.S. Congress set about providing liberal pensions for veterans. On December 28, 1818, James Lafayette, 70, petitioned the Virginia General Assembly for pension relief, reporting that his health had declined such that he found it difficult to work. “In tender consideration whereof,” his petition read, “he Humbly prays that your Honorable body will pass a law, allowing a small sum for Emediate relief, and such moderate pension for the remnant of his days as in your wisdom shall seem just.” The Assembly allotted James Armistead Lafayette $60 for “present relief” and a lifetime pension of $40 annually.

Returning to his native France after the war, Lafayette, a staunch foe of slavery, urged American President George Washington to remove the stain of that institution from the new nation. Under the traditional English practice of “free tenancy,” tenant farmers paid low rents and landlords imposed fewer restrictions. As an experiment whose aim would be to emancipate participating slaves, Lafayette proposed that he and the president each purchase land for slaves to work as free tenants rather than as bondsmen. Lafayette hoped the symbolic gesture would catch on in the United States and the West Indies. Lafayette planned to dedicate holdings he had bought in French Guiana in 1785 to this purpose, but Washington proceeded much more slowly and never fully implemented his part of the plan.

The Marquis de Lafayette’s life in France was marked by turmoil. Initially he held prestigious roles: appointment to the Assembly of Governors, election to the Estates-General, a hand in drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. After the storming of the Bastille, Lafayette, as commander in chief of the National Guard, tried to steer a middle course through the revolution. In August 1792, radical factions ordered his arrest. Lafayette fled to a region ruled by Austria and comprising the southern Netherlands, western Belgium, and much of Luxembourg. There, Lafayette was captured, tried, and sentenced to five years in prison. In 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte secured his release, and after the Bourbon Restoration of 1814, Lafayette became a liberal member of the French Chamber of Deputies.

In 1824, President James Monroe invited Lafayette to the United States. The marquis, 66, toured all 24 states, greeted by rapturous crowds and appreciative politicians. At the field in Yorktown where the British surrender had taken place 43 years before, his open carriage was moving slowly through cheering masses when its occupant spied a familiar face. Ordering his driver to halt, the marquis stepped into the crowd to embrace his old friend, secret agent, and now namesake, James Armistead Lafayette. Reported the Richmond Enquirer, “A black man even, who had rendered him services by way of information as a spy, for which he was liberated by the State, was recognized by [the marquis] in the crowd, called to him by name, and [was] taken into his embrace.”

The Marquis de Lafayette was 76 when he died in 1834, having outlived James Armistead Lafayette, who died on August 9, 1830. In February 1865, Virginia ratified the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which outlawed slavery. “By carrying information to Washington and Lafayette during the final days of the American Revolution, James Lafayette had won his own freedom and contributed to the cause of American independence,” John Salmon, head of the state records unit of the Archives and Records Division of the Virginia State Library, wrote in the Autumn 1981 Virginia Cavalcade. “His was a victory that subjected the institution of slavery itself to the relentless ‘contagion of liberty’ that has prodded America to honor the fullest implication of its professed belief that ‘all men are created equal.’”

This article was written by Larry C. Kerpelman and originally published in the October 2018 issue of American History. For more stories, subscribe here.