In May 1915 Arthur Guy Empey, a 31-year-old recruiting sergeant with the New Jersey National Guard, was sitting in his office in Jersey City. It was a warm, pleasant spring day, and through his window, Empey—a sturdy man with an animated, energetic manner—could hear a street musician turning the crank on a hurdy-gurdy and playing a popular melody of the time, “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier.”

For Empey, the tune clashed discordantly with the top headline in the newspaper on his desk: lusitania sunk! american lives lost! He looked to a massive wall map of Europe; small flags pinned to it showed the positions of the German and Allied armies along the Western Front in France. A National Guard lieutenant silently went over to his desk, took an American flag from his drawer, and solemnly draped it over the map. “How about it, Sergeant?” the lieutenant said to Empey. “You had better get out the muster roll of the Mounted Scouts, as I think they will be needed in the course of a few days.” The two men worked into the evening, preparing telegrams telling guard members to report for duty so that the messages could be sent as soon as word came from Washington, D.C.

But the orders they were waiting for didn’t come. After a few months, Empey’s lieutenant, sighing with disgust, took the American flag and put it back in his desk. Empey took the dusty stack of telegrams and pitched them in the trash. He felt depressed and uneasy.

A native of Ogden, Utah, whose family had moved back East, Empey had spent most of his adult life in uniform. After high school, he started out as a sailor in the U.S. Navy, where he’d nearly been killed in a turret explosion. He’d then enlisted in the U.S. Cavalry, where he’d attained the rank of sergeant major, become an expert marksman and equestrian, and patrolled the border during the Mexican Revolution. Now, he was spoiling for a fight with the Germans. One day, he abruptly decided that if President Woodrow Wilson wasn’t going to send him to fight, he’d go on his own. He booked passage on a ship to England and showed up at a British Army recruiting station on Tottenham Court Road in London, wearing an American flag pin on his lapel. Initially, he was turned down because he was from a neutral country, but a recruiting sergeant followed Empey outside and said he could take him to a lieutenant at another office who would be willing to bend the rules for him.

Soon Empey was serving in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, as the British Army’s City of London Regiment was known. Fully outfitted—hobnail steel-toed boots, puttees, bayonet, entrenching tool, felt-covered canteen, waterproof sheet, heavy woolen “trench cap”—Empey shipped out for France. He was about to experience the horrors of trench warfare, but that harrowing experience would, on his return home, help to make Empey one of the most famous people in America: a best-selling author, a lecturer who filled theaters, and a silent movie star and early Hollywood celebrity. But Empey’s meteoric ascent, fueled by his own talent for self-promotion, would be followed by an even steeper decline into controversy and, finally, obscurity. It’s a quintessentially American story of a man who struggled to live up to the legend he had created.

Empey arrived at Rouen, France, carrying the Lee-Enfield rifle he’d been issued. He was soon given a steel helmet, two “gas helmets,” a couple of blankets, and a tin of antifrostbite grease. He plunged into 10 days of intensive training on the rudiments of trench warfare, from putting up and repairing barbed wire to the procedures that should be followed during enemy poison-gas attacks. Then he and his British comrades headed off to the Western Front.

Empey soon found that life in the trenches was a mix of squalor and unnerving experiences—from the ever-present rats and lice to the continual German shelling to the ubiquitous mud. “The men slept in mud, washed in mud, ate mud, and dreamed mud,” he would later write. “I had never before realized that so much discomfort and misery could be contained in those three little letters, MUD.”

But worst of all was when Empey and the others climbed out of the trenches and rushed into no man’s land to confront the Germans at close range. Empey later recalled one such foray, in which he was enveloped in a wave of carnage: “Tommy about 15 feet to my right front turned around and looking in my direction, put his hand to his mouth and yelled something which I could not make out on account of the noise from the bursting shells,” he wrote. “Then he coughed, stumbled, pitched forward, and lay still. His body seemed to float to the rear of me.” Empey tried to remember his bayonet instructor’s admonitions as he shut his eyes and plunged forward. He felt his rifle torn from his grip, as his bayonet sliced into a German soldier. “I must have gotten the German, because he had disappeared,” Empey recalled. He watched a towering German battle three British soldiers, smashing one’s skull like an eggshell with the butt of his rifle before another got behind him and slammed a bayonet into his neck, so that the point came out through his throat. Empey saw the look of astonishment on the German soldier’s face as he fell.

In a moment, Empey felt something hit his left shoulder, and his side went numb. “It felt as if a hot poker was being driven through me,” he later recalled. “I felt no pain—just a sort of nervous shock. A bayonet had pierced me from the rear. I fell backward on the ground, but was not unconscious, because I could see dim objects moving around me. Then a flash of light in front of my eyes and unconsciousness.” When he woke up, he was back in the trenches, being carried on a stretcher.

After spending six weeks in the hospital recovering from his injuries, Empey rejoined his outfit. Along with several other soldiers, he was sent to a school for “bomb throwing.” The so-called Mills bombs were early iterations of fragmentation grenades, and before long Empey qualified as a “bomber.”

In July 1916, in the opening days of the Battle of the Somme—the “Big Push,” British soldiers called it—enemy machine guns opened up as Empey and his mates charged the German trenches. Taking cover in the darkness, he reached over and touched the body of one of his comrades and discovered that the top of the man’s head had been blown off. He got up again, and a bullet hit him in the shoulder. The fear was gone, replaced by rage. He pulled the pin from a grenade and threw it blindly at the German trench just 10 feet away. He saw two German soldiers fall backward and crumple. He turned and ran back through the barbed wire as the surviving Germans opened fire on him. He was hit in the shoulder and in the face. Then everything went black.

The doctor who treated Empey told him that he had lain unconscious in no man’s land for a day and a half and that it was a wonder he was alive. Of the 20 men in his raiding party, 17 had been killed. Empey had lasted a year in the British Army, but now, for him, the war was over. It was time for him to start creating his legend.

At the American Women’s War Hospital near Paignton, England, a Harvard-trained surgeon rebuilt Empey’s battered face, grafting a piece of bone from a cadaver rib to fill the hole that a bullet had left in his cheek. After a lengthy recovery, Empey returned to America. He tried to enlist in the U.S. Army but was rejected because of his injuries.

Having been declared unfit for military service, Empey decided to bring the war home to Americans. He began giving lectures at clubs in New York, describing his experiences on the Western Front. He turned out to be a surprisingly riveting speaker. He had a trick of standing with one foot on the seat of a chair in the middle of a stage, as if he were on the edge of a frontline trench, while he described combat to his listeners. The jagged red scar on his cheek, faint but still perceptible, was evidence of what he had experienced.

Robert Gordon Anderson, a sales manager and occasional writer for the publishing house of G. P. Putnam’s Sons, went to one of Empey’s lectures and came away thinking that the ex-soldier’s adventures would make a best-selling book. Empey agreed to collaborate with Anderson, and the two men produced a memoir, Over the Top.

The book reached stores in 1917, shortly after the United States entered the war, which turned out to be perfect timing. Over the Top was an immediate success, selling nearly a million copies.

While depicting the hardships and gory mass slaughter of modern combat in vivid detail, Over the Top was also a clever piece of propaganda, aimed at shaming Americans into enlisting. “War is not a pink tea,” the book warns, but the hardships and peril endured by soldiers “are far outweighed by the deep sense of satisfaction felt by the man who does his bit.”

Though Empey had served only briefly in combat, Over the Top made him into one of the war’s most famous heroes and an instant celebrity. Shortly after publication, he embarked on a nationwide promotional tour that doubled as an opportunity to recruit soldiers for the war effort. Variously reading passages from his book, boosting the sale of Liberty Bonds, and speaking about America’s need for volunteers, Empey became one of the nation’s most effective and charismatic purveyors of government war propaganda. According to one newspaper account he sold more than $1 million in war bonds.

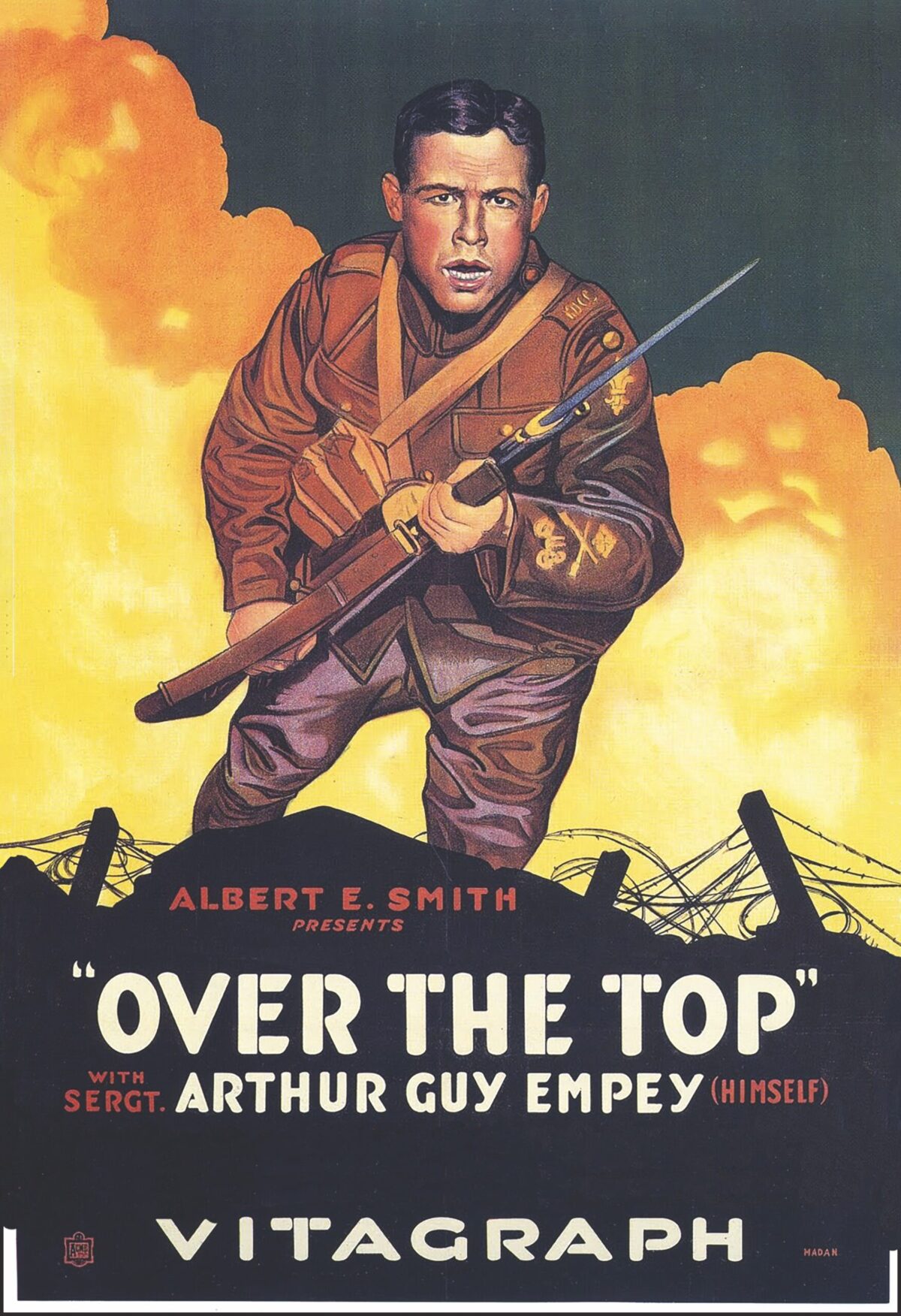

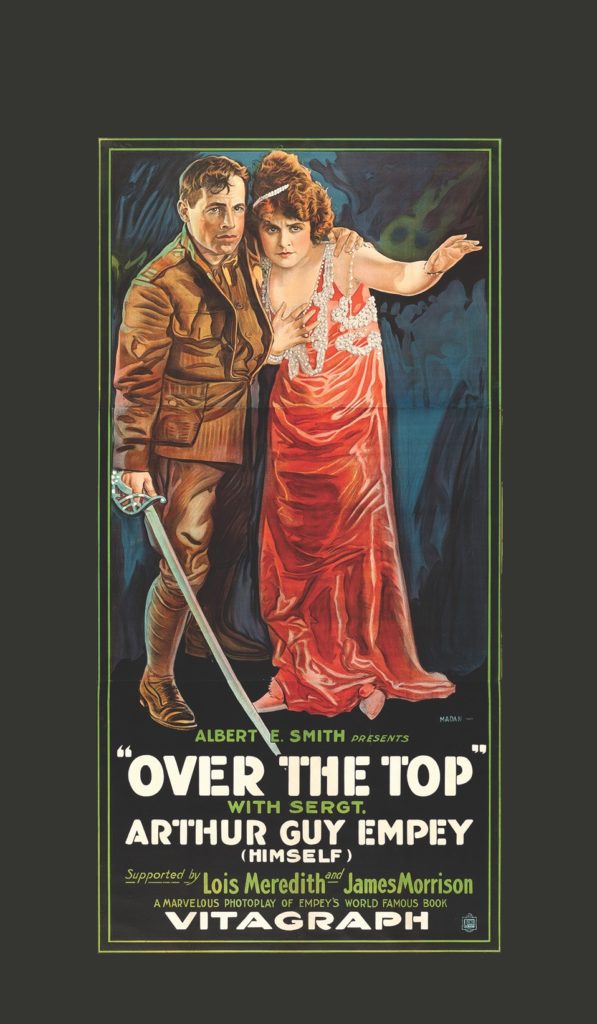

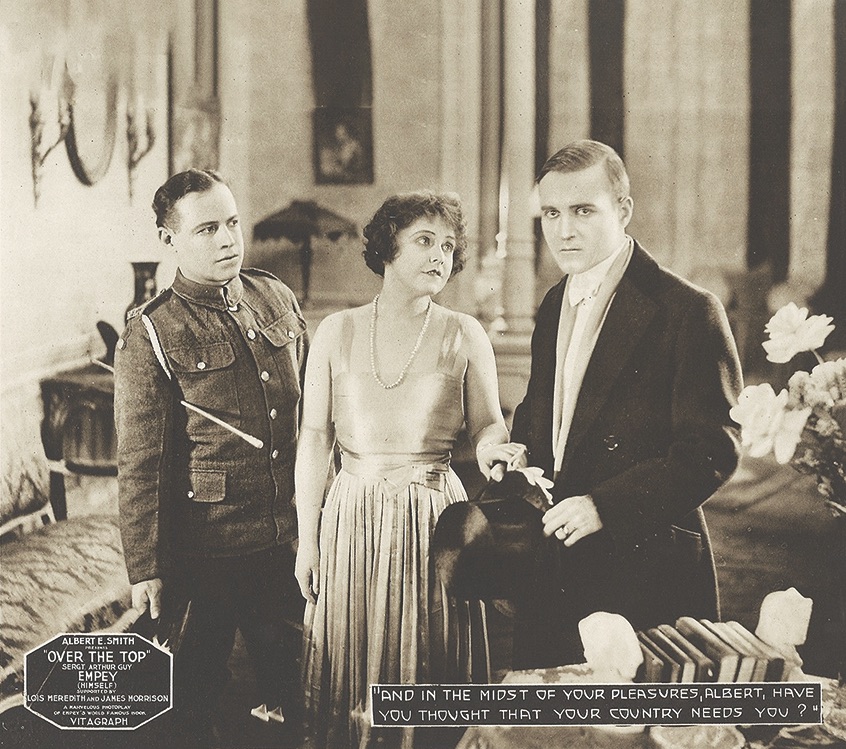

Empey’s skill as a performer apparently caught the attention of Vitagraph, a Brooklyn-based movie studio, which hired Anderson to adapt the book into a screenplay. The studio also offered Empey a chance to portray a version of himself on the screen, and he agreed.

As with many other silent films, no print exists of Over the Top (1918), which oddly bore little resemblance to the book, instead using the war mostly as a backdrop for melodrama. In it, Empey’s character, James Garrison “Garry” Owen, joins the British Army and, after being wounded in combat, returns to the United States. While in New York he falls in love with Helen, and they plan to marry after Owen returns from fighting with the American forces in France. Improbably, a German officer abducts Helen and takes her by submarine to Europe. Amping up the romantic drama, Owen is also captured by the Germans and forced to attend a banquet celebrating the German officer’s marriage to Helen. But after a servant poisons the German wedding guests, Owen kills the officer, and he and Helen escape to Allied territory.

Over the Top opened at the Lyric Theater in New York City on March 31, 1918. Advertisements in local newspapers for the 10-reel film, billed as “Vitagraph’s Stupendous Photo-Play of Empey’s World-Famed Book,” noted that “Sergeant Empey will appear personally tonight and at every performance for the first week.” In June, President Wilson attended the Washington premiere of Over the Top at the Strand Theater—which featured painted scenery, a fabricated trench, and a live orchestra—with his wife and members of his cabinet.

Cheesy as it may have been, Over the Top was apparently successful enough to launch Empey on a new career as an actor. In the summer of 1918, he appeared in a play, Pack Up Your Troubles. Around that time, the U.S. Army recognized Empey’s contribution to the war effort by commissioning him as a captain in the Adjutant General’s Department.

But Empey’s career as an officer ended before it had even started. According to the New York Times, after performing in Pack Up Your Troubles at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C., he used the curtain call to make a short speech in which he paid tribute to the soldiers in the French and British armies. Empey said those volunteers were the real heroes, because they’d fought willingly—unlike the Americans who’d gone to war because they’d been drafted. The stunned audience—which included President Wilson—didn’t applaud him. A few days later, Empey’s commission was withdrawn, and he was discharged from the army. Wilson’s secretary sent him a letter, explaining that having Empey recruit volunteers would interfere with “the orderly selective process.”

But Empey didn’t let the embarrassment stop him. He had become friends with movie stars such as Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, and he soon moved to Hollywood, where he used the royalties from the book and movie versions of Over the Top to start his own studio, the Guy Empey Pictures Corporation, where he would work as a producer, screenwriter, and actor. Empey churned out a succession of pictures, such as The Undercurrent, Millionaire for a Day, The Midnight Flyer, and Into No Man’s Land, a contrived 1928 drama about a jewel thief and an investigator who reencounter one another in the trenches in France.

Empey continued his career as a writer as well, mostly producing books with a military slant, with titles such as A Helluva War. He even tried his hand as a songwriter, composing the lyrics to such patriotic ballads as “Our Country’s In It Now, We’ve Got to Win It Now,” “Liberty Statue Is Looking Right at You,” and “Your Lips Are No Man’s Land but Mine.”

Empey also continued to be in demand as a public speaker. In 1922, for example, he gave an impassioned address to a meeting of the Daughters of the American Revolution in Washington, D.C., in which he touted “real Americanism.” Among other things, he urged the DAR to pressure Hollywood to feature American heroes and stories rather than European ones—an odd stance for a man who had once extolled the virtues of British and French soldiers.

Empey also began pounding out World War I–themed short stories for magazines such as War Stories, Battle Stories, and War Birds, featuring a hard-drinking, roughneck soldier hero named Terence X. O’Leary.

By the end of the 1920s, however, Empey’s star was rapidly fading. Silent films were on the way out, and the reading public had grown tired of books and stories with World War I themes. Also, Empey apparently wasn’t very good at managing his finances. In March 1929, a front-page story in the Los Angeles Times revealed that the former war hero had declared bankruptcy, with liabilities of $124,417.35 and assets of just $420, including two typewriters.

Empey, like many others in the motion-picture industry, was unable to navigate the transition to talkies. He was involved in one last silent movie, Troopers Three, a 1930 comedy. (Empey was credited with the story.) The film, set in the U.S. Cavalry, was billed as “The Greatest Laugh Hit of the Year.” It wasn’t. The film flopped, and Empey’s movie career was over.

In an effort to keep his writing career going, Empey gradually transformed his O’Leary character, converting him from a lout into an increasingly savvy and sophisticated adventurer—veteran of the French Foreign Legion, secret agent, ace fighter pilot, and commander of the “Black Wings Pursuit Squadron.” He made his villains increasingly fantastical as well, switching from nefarious Germans to outlandish characters like Unuk, the evil 500-year-old immortal high priest of the God of the Depths, and his right bower, Umgoop the Horrible, high priest of the subaquatic kingdom of Neptunia. Instead of machine guns and mustard gas, O’Leary now faced chemical mind control and a flotilla of airships equipped with death rays.

But the science fiction–fantasy approach never caught on, and in 1936 Empey’s publishers dropped his O’Leary series. His career as a pulp novelist was over as well.

Behind Empey’s carefully cultivated image as a patriotic hero, he had a darker, disturbing side. His writing sometimes had anti-Semitic overtones—in Over the Top, for instance, he created a New York “money lender” named Ikey Cohenstein, and Tales from a Dugout includes an anecdote about a recruiting official whom Empey describes as “a little fat, greasy Jew.” By the mid-1930s, with his creative career on the wane and his World War I exploits fading in the public memory, Empey tried to remake himself again—this time as a leader in the nascent far-right, nativist movement seeking to counter President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the labor movement, and the leftist leanings of many in Hollywood.

Empey founded an organization called the Hollywood Hussars. Headquartered at the Hollywood Athletic Club, his volunteer paramilitary cavalry militia included signal and medical teams, an intelligence section, a motorcycle dispatch wing, and an MP-style police force. Its members wore natty uniforms, drilled regularly on horseback and on foot, and took firearms instruction. He described it as a “military-social unit, devoted to the advancement of American ideals.” The former sergeant assigned himself the rank of colonel.

While Empey was no longer a film star, his name was still familiar enough—especially in Hollywood—that his organization attracted national attention. Reportedly, publishing mogul William Randolph Hearst was one of its supporters. For his personnel director, Empey chose Edwin C. “Ted” Parsons. Parsons was a man after Arthur Empey’s own heart, having served as a pilot in the famed Lafayette Escadrille (he was an eight-victory ace), a special agent for the FBI, a technical consultant on high-budget war films, and a writer and radio narrator of his own wartime experiences. Parsons would eventually serve in the U.S. Navy during World War II, rising to the rank of rear admiral.

The Hussars soon boasted a roster that included some of Hollywood’s most prominent conservative celebrities, including actors Ward Bond and Gary Cooper. Cooper was America’s highest paid and most popular movie star, and his imprimatur lent further legitimacy to Empey’s organization. Cooper initially described the group as motivated by “Americanism,” which Hollywood political historian Donald T. Critchlow has noted was used by some as a code word for allegiance to the far right.

As Empey explained to the Motion Picture Herald, the Hollywood Hussars were “armed to the teeth and ready to gallop on horseback within an hour to cope with any emergency menacing the safety of the community, fights or strikes, floods or earthquakes, wars, Japanese ‘invasions,’ communistic ‘revolutions,’ or whatnot.” But according to Jimmy Stewart biographer Donald Dewey, Empey had another, even more bizarre ambition: invading the Soviet Republic of Georgia to secure oil drilling rights for an American millionaire who was one of the organization’s chief financial backers.

In May 1935, journalist Carey McWilliams wrote a column for the widely read Nation magazine under the heading, “Hollywood Plays with Fascism.” In it, he pilloried Cooper and others in the Hussars, referring to them as “warriors-in-make-up,” and to Cooper specifically as a “movie-lot Bengal Lancer.” McWilliams accused them of “permit[ting] their names to be used as sponsors for fascist groups in Hollywood.”

Suddenly finding himself in the middle of a red-hot controversy, Cooper hastily announced that he had quit the Hussars. In a statement to the press that was almost certainly written by the Warner Bros. public relations department, he said, “The Hussars are not the social group I had thought….The men behind it are trying to organize a national, semi-military organization of a political nature.”

Meanwhile, the Hollywood Hussars continued to drill under the instruction of active-duty police officials and retired army officers.

Empey’s vitriolic rhetoric aside, the Hollywood Hussars ultimately proved quite harmless, spending their time parading and posturing in uniform, giving speeches, practicing military maneuvers, playing polo, and staging social galas. There were no pall-mall horseback dashes to rescue the community from fights, strikes, floods, “Japanese invasions,” or “communistic revolutions,” nor did the community find the need to call on this band of misguided patriots for anything more challenging than what most of them already provided—entertainment.

In forming the Hollywood Hussars, Empey had attempted to recreate a cavalry unit reminiscent of his first military experience but with an extremist agenda. In the end, despite his goal of taking the Hussars nationwide, the organization lasted less than a year. The fiasco would provide a strange coda to his once promising Hollywood career.

During World War II, Empey resurfaced briefly, when a reporter for the Associated Press found him working the graveyard shift as a plant guard at the Burbank factory of Vega Aircraft Corporation. He told the wire service that it was the “first real job” that he’d ever had and that he was doing it to contribute to the war effort and to gather material for a novel about defense plant workers.

But Empey noted that World War II wasn’t the great adventure that the previous war had been. Warfare had turned into “a grim, cold and deliberate job,” he said.

Empey never published that last novel. Instead, he slipped back into obscurity; his world had vanished. He didn’t show up in the news again until 1963, when he died at the Veterans Hospital in Wadsworth, Kansas, at age 79. The man who’d once been among the most celebrated heroes of World War I left behind little more than his British Army citations—two campaign medals and an honorable discharge badge.

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Self-Made Hero