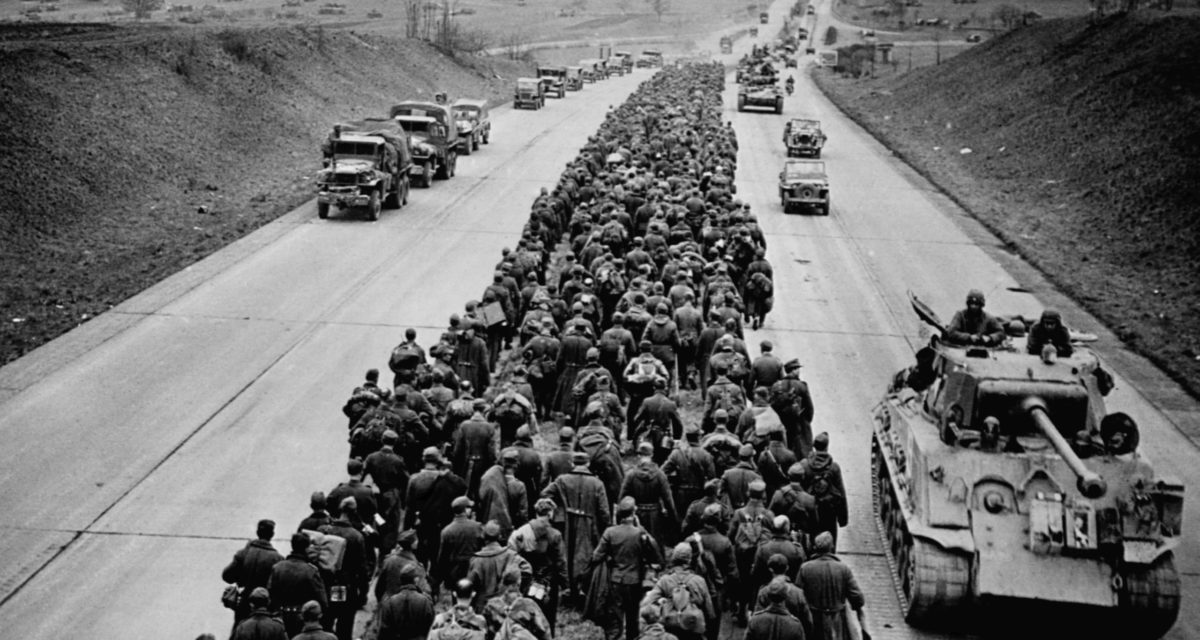

Eighty-five German POWs, identified as dedicated anti-Nazis, worked to reeducate their countrymen interned in nearly five hundred camps across the United States

By early 1944 the reign of terror and intimidation by hard-core Nazis interned in American prisoner-of-war camps had become so widespread that an intrepid woman journalist decided to do something about it. Dorothy Thompson was a widely syndicated newspaper columnist who, in 1934, had been the first American journalist to be kicked out of Nazi Germany. She came home so incensed that she reportedly hauled off and socked a woman who made pro-Nazi remarks in her presence.

Now, hearing reports that Nazis in American camps were beating, murdering, and forcing the suicides of fellow German POWs, Thompson went to the White House to see her good friend Eleanor Roosevelt. She talked to the First Lady about the Nazi terror campaign in the camps and suggested that the United States should be taking the opportunity to reeducate German POWs by teaching them lessons in democracy.

Shocked by what she heard, Eleanor Roosevelt promptly invited an official in the army’s prisoner-of-war administration to dinner at the White House. Maj. Maxwell McKnight was chief of the administrative section of Prisoner of War Camp Operations—a Yale graduate, former United States Attorney, and, most important, member of a prominent New York family who would have moved in the same social circles as the Roosevelts. “I’ve been hearing the most horrible stories about all the killings that are going on in our camps with these Nazi prisoners,” she told McKnight.

As McKnight already knew, a reeducation scheme aimed at countering Nazi domination of the camps had been gathering dust at the War Department for nearly a year. The main obstacles were the lack of qualified personnel to carry out such a

program, and the provision of the Geneva Convention that prohibited indoctrination of prisoners of war. But after Eleanor Roosevelt spoke to McKnight and then her husband, and after President Roosevelt conversed with his secretaries of war and state, the controversial idea was revived.

During the summer of 1944, the government launched an ambitious and secret effort to influence the nearly three hundred eighty thousand Germans imprisoned in the United States. Through newspapers, books, movies, and classroom education, they would be given “the facts, objectively presented,” said a War Department memo, “but so selected and assembled as to correct misinformation and prejudices.” Secretary of War Henry Stimson ordered that the goal “should not be the improbable one of Americanizing the prisoners, but the feasible one of imbuing them with respect for the quality and potency of American institutions.”

The army imposed a tight veil of secrecy over the program. Planners feared that publicity might cause the prisoners to resist reeducation and that Germany might retaliate with its own indoctrination program. There was also the matter of the Geneva Convention. But someone noted a loophole in the document’s Article 17, which read, “So far as possible, belligerents shall encourage intellectual diversions and sports organized by prisoners of war.” Thus originated the official and innocuous cover name for this grand scheme in reeducation—the Intellectual Diversion Program.

[continued on next page]