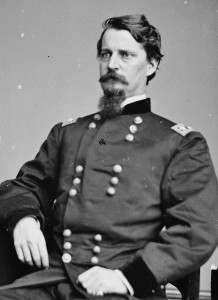

The 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th Vermont Volunteer Infantry regiments comprised the so-called “Second Vermont Brigade.” All regiments were nine month enlistments, and went into service in October, 1862. The brigade came into existence on 27 October 1862. Through most of its existence, it was part of the vast defenses of Washington, D.C.. But with General Robert E. Lee’s army invading Pennsylvania, the brigade joined the Army of the Potomac as the 3rd Brigade in the 3rd Division of the 1st Corps on 25 June 1863. Its commander was Brigadier General George Stannard.

The 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th and 16th Vermont Volunteer Infantry regiments comprised the so-called “Second Vermont Brigade.” All regiments were nine month enlistments, and went into service in October, 1862. The brigade came into existence on 27 October 1862. Through most of its existence, it was part of the vast defenses of Washington, D.C.. But with General Robert E. Lee’s army invading Pennsylvania, the brigade joined the Army of the Potomac as the 3rd Brigade in the 3rd Division of the 1st Corps on 25 June 1863. Its commander was Brigadier General George Stannard.

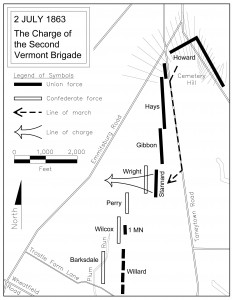

The 12th and 15th regiments had taken an assignment to guard trains at Westminster, Maryland when the battle of Gettysburg broke out on 1 July. The 13th, 14th and 16th Vermont Regiments arrived on the battlefield late that night. They stayed in reserve on the south side of Cemetery Hill. First Sergeant George H. Scott of the 13th Vermont explained how the brigade received the call to action in the late afternoon of 2 July:

Col. Randall [commanding the 13th Vermont] saw that Sickles and Hancock were being worsted and felt that his regiments would soon be needed. He mounted his horse and stood ready for action.

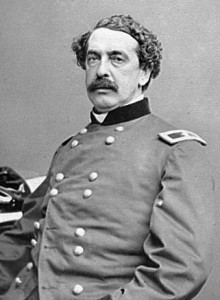

He soon saw an officer mounted and coming with all speed towards him. On seeing the regiment, he halted and thus addressed Randall. “Colonel what regiment do you command”? “The 13th Vermont, Sir,” said Randall. “Where is General Stannard”? Randall replied, pointing to a clump of oaks some 70 rods away. He then said “Colonel will your regiment fight”? “I believe they will sir.” Said Randall “Have you ever been in a battle, Colonel”? Randall replied “I have personally been in most of the engagements of the Army of the Potomac since the war began, but my regiment being a new organization has seen but little fighting, but I have unbounded confidence in them.” The officer then said “I am General Doubleday. Introduce me to your regiment. I command your corps.” Randall rode with him close up to the regiment, and said “Boys, this is General Doubleday, our Corps commander.” He addressed us substantially as follows:

“Men of Vermont: The troops from your state have done nobly and well on the battle fields of this war. The praises of the old Vermont brigade are on every lip. We expect you to sustain the honor of your state. Today will decide whether Jefferson Davis or Abraham Lincoln rules this country. Your Colonel is about to lead you into battle where you will have hard fighting and much will be expected of you.” – –

The Vermont boys gave three cheers for Doubleday. Doubleday then requested Randall to take his regiment… and report to Hancock; at the same time requesting him to make all speed as Hancock was hard pressed and was losing his artillery. This order Randall at once obeyed. Doubleday then directed Stannard to report to Hancock.

Major General Winfield Scott Hancock normally commanded the 2nd Corps, but presently was taking Major General Dan Sickles’ place, who was badly wounded, in command of the 3rd Corps. He had been scrambling most of the late afternoon to keep Cemetery Ridge out of Confederate hands. It was a very tall order, as Sickles had previously moved his corps almost a mile in front of its assigned position. The Confederates had taken advantage of Sickles’ isolation, charging through it and advancing to Cemetery Ridge in its rear. Hancock had desperately pieced together reinforcements from various parts of the field to save the ridge. As the Vermonters arrived, Hancock was facing Wright’s and Perry’s Confederate brigades, making off with three of his artillery pieces. Sergeant Scott’s description continued:

The 14th Regiment under Col. Nichols led the way under a sharp fire to the rear of a battery, from which our men had been driven in confusion. The enemy fell back as they advanced. The 16th under Col. Veazey also advanced and came on a body of rebels, as they were rushing upon a battery. They fled as the 16th approached and formed behind the battery, which they found without supports, and this the 16th supported until dark. Agreeably to Doubleday’s order Randall spoke a few words of cheer to the left wing of his regiment, told them that we had met with a disaster and the 13th must go out and retrieve it. And then at the command “Attention; by the left flank, march”! We started toward the southwest, up the hill at a quick step.

Randall rode on and met Hancock, who was rallying his men and encouraging them to hold on to the last. A few hardy fellows were taking advantage of the ground to contest the advance of a rebel brigade in their front. As Hancock saw Randall, he said “Colonel, where is your regiment”? “Close at hand” said Randall. “Good,” said Hancock, “the enemy are pressing me hard – they have just captured that battery yonder (a battery about 20 rods in front) and are dragging it from the field. Can you retake it”? “I can, and damn quick too, if you will let me.”

Colonel Randall was a veteran and an unapologetic self-promoter. His detailed report provides an unusual view into the complexity of maneuvering hundreds of men in an organized manner:

By this time my regiment had come up and I moved them to the front far enough so that when I deployed them in line of battle they would leave Hancock’s men in their rear. They were now in columns by divisions, and I gave the order to deploy in line, instructing each captain as to what they were to do as they came on to the line, and, taking my position to lead them, gave the order to advance.

Sergeant Scott remembered:

We had not gone ten rods ere Randall’s horse fell shot through the neck. His regiment faltered. Randall cried, at the same time pulling vigorously at his foot which had got caught in the stirrup, between the horse and the ground, – “go on boys I’ll be at your head as soon as I get out of this damned saddle.” Several boys stepped up and rolled off his horse. Soon he came running around the side of the regiment to the front, on foot, limping badly, his hat off, his sword swinging in the air, saying, “I am all right. Come on boys, follow me.” He led us into the gap.

According to Randall, Hancock was available to assist the Vermonters though beset with several emergencies along his line:

General Hancock followed up the movement, and told me to press on for the guns and he would take care of the prisoners, which he did, and we continued our pursuit of the guns, which we undertook about half way to the Emmitsburg road, and recaptured them with some prisoners. These guns, I am told, belong to the Fifth U.S. Regulars, Lieutenant Weir. There were four of them.

One of Scott’s accounts incorporated a Hancock quote:

Hancock says “I recollect of telling the officers and men where to leave the pieces or how far back to take them and remained with them for a few moments. I was anxious that they should not delay too long by carrying pieces too far, so that they would not be delayed in advance.”

If one is to believe Scott, Hancock need not have worried about how far these men could carry their expedition:

After leaving the guns, we turned about and pursued the enemy a half mile… We drove the enemy down into the peach orchard until we reached a farm house on the Emmittsburg road, where we halted and fired some 15 rounds into the enemy.

That was only the beginning of Scott’s tale of triumph:

In the meantime Capt. Lonergan, in command of Company “A” approached a house and found it full of rebels. He informed Randall of the fact, who went up and ordered them to throw their guns out the window and surrender, which they did. At which time Col. Randall, ever mindful of his laurels, remarked to them “remember you were captured by Col. Randall of the 13th Vermont.”

“Col. Randall was not the most modest man in the world” explained Scott. “He was fond of his regiment and was determined that the world should recognize every laurel it won.” Night was surely falling as his regiment, along with the rest of the brigade, was returning to Cemetery Ridge. But Sergeant Scott explained that Randall was not yet done:

So on getting within twenty rods of our main lines he ordered us to halt and lie down to rest. Soon an aide from the General came riding down to us whom the Colonel addressed as follows:

“Captain, report to your General what we have done. We have recaptured six guns, taken two from the enemy, driven him half a mile and taken a hundred prisoners. Also tell him we propose staying here until he acknowledges our achievements.”

While waiting for acknowledgement that he was the God of War himself, however, discretion finally got the better part of Randall:

Randall soon discovered the enemy were trying to flank us and take us prisoners, and preferring to lose his laurels than spend the Fall in Libby Prison, he led us back to our original lines.

But Randall would get his praise anyway, according to Scott:

As the 13th approached our troops, cheer after cheer, long and loud, rang along our lines for the gallant Vermont boys in their first action… Gen. Doubleday sent his aides to compliment and thank the 13th for their gallantry. Randall says, “It was dark by this time, and on getting back to our lines my first point was to find the Brigade. I soon met one of Gen. Stannard’s aides. On seeing me he said, ‘Where in Hell have you been? The General has been looking all over the field for your Regiment.’ I inquired where the General was, and he showed me, and I approached the General and he rebuked me for wandering off without orders. I told him I followed General Doubleday’s orders and I supposed that to be right. By this time a half dozen aides from Hancock, Doubleday, and others surrounded me with congratulations from their chiefs.”

The Vermonters had made their charge at a time and place that essentially ended the Confederate assault on the Union left and left center. The attacking wave was finally spent; and it had reached the ground where Gibbon’s 2nd Corps division stood ready and waiting.

For further reference, see Observing Hancock at Gettysburg: The General’s Leadership through Eyewitness Accounts by Paul E. Bretzger, McFarland and Company, 2016.