Happy birthday, Mr. President…

Marilyn Monroe’s intimate 1962 rendition of the “Happy Birthday” song to President John F. Kennedy was about as subtle as a bull in a china shop.

No history of U.S. presidential scandals would be complete without a glimpse into the many affairs that fueled them.

In fact, it’s hard to find a president who was untouched and above the salacious fray.

So in honor of Cupid’s annual day, in which we show our romantic partners—married or not—how special they are, here are some of the lesser-known presidential love affairs and scandals you may not have read about.

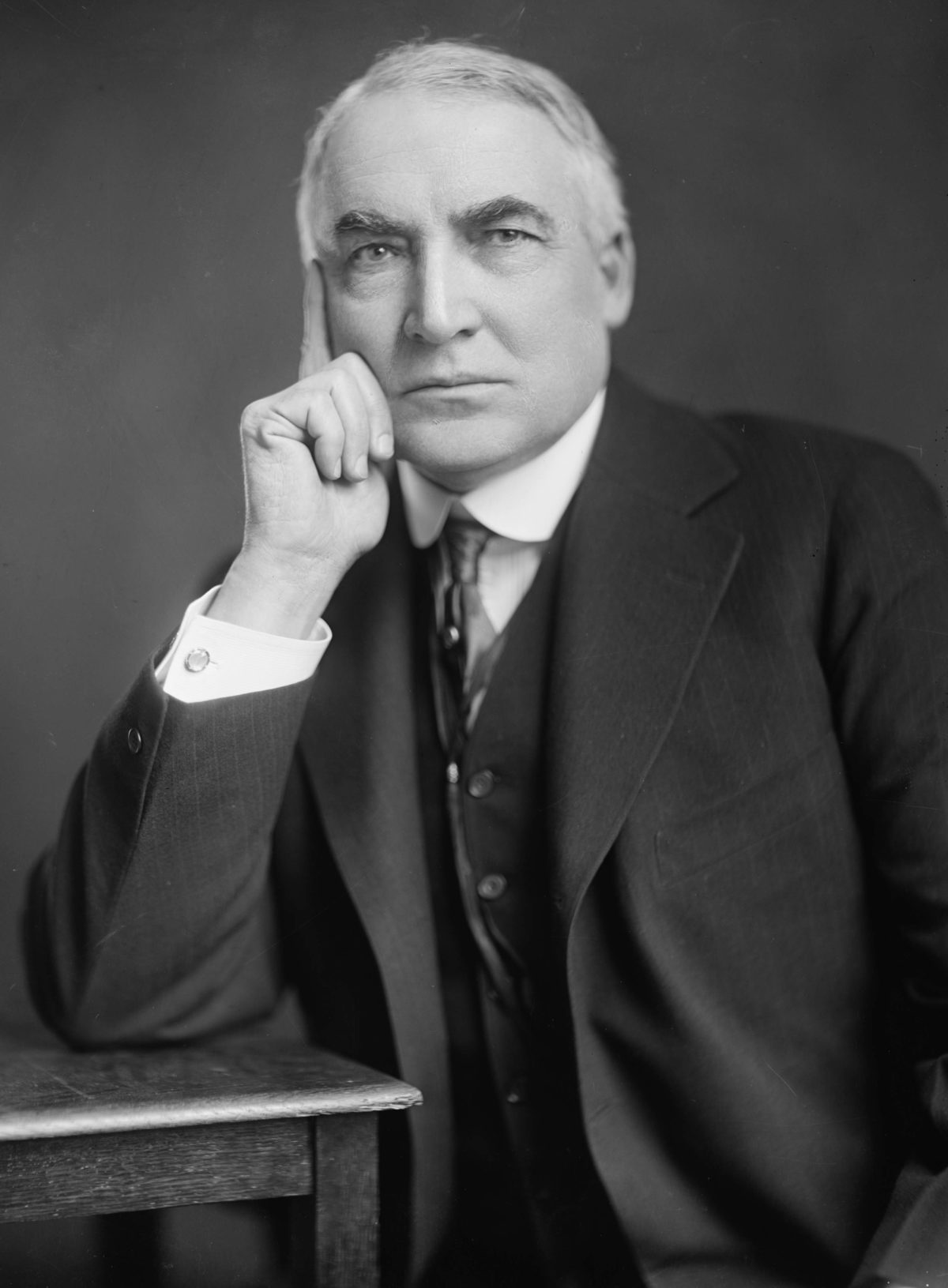

Warren G. Harding

Harding’s presidential reputation has not aged well. While generally regarded as one of the worst presidents in U.S. history, Harding is largely remembered (although if ever) for his extramarital affairs.

According to James David Robenalt, an Ohio attorney and author, Harding’s affair with the married Carrie Fulton Phillips began in 1905 and spanned nearly 15 years.

Known for his staid public persona, Harding certainly didn’t hold back in expressing his passion for her through the written word:

“My Darling,” he began in a Dec. 24, 1910 letter. “There are no words, at my command, sufficient to say the full extent of my love for you—a mad, tender, devoted, ardent, eager, passion-wild, jealous… hungry… love…”

“It flames like the fire and consumes,” the married Harding continued. “It racks in the tortures of aching hunger, and glows in bliss ineffable—bliss only you can give.”

Perhaps in one of his more emotionally sober moments, Harding implored Phillips to burn his letters to keep them from prying eyes, writing, “I have been thinking about all those letters you have,” he wrote to her on Jan. 2, 1913. “I think you [should] have a fire, chuck ’em! Do. You must. If there is one impassioned one that appeals to you, keep it… [but] please, chuck the extra pictures, letters and verses. They are too inflammable to keep.”

Yet even after that request, following a particularly amorous weekend spent together in New York in September 1913, Harding wrote to Phillips:

“I do not know what inspired you, but you… resurrected me, and set me aflame with the fullness of your beauty and the fire of your desire. … imprisoned me in your embrace and gave me transport—God! My breath quickens to recall it.”

Thankfully for us all, Phillips refused Harding’s request to destroy their correspondence, and their letters are now free for viewing on the Library of Congress website.

But Harding’s amatory exploits weren’t over just yet.

A wife plus a lover just weren’t enough for the insatiable man—while his affair was still ongoing with Phillips, Harding fathered a daughter out of wedlock with Nan Britton. Although the paternity of the child, Elizabeth Ann Blaesing, was disputed for nearly a century, Ancestry.com confirmed in 2015 that DNA testing showed Harding was a familial match.

Harding died in office in 1923, and the news of his sordid affairs quickly spread, tarnishing his reputation forever more.

Grover Cleveland

Perhaps there is some cold comfort in the fact that throughout U.S. history, political campaigns have always been, more often than not, smear campaigns.

The bitter presidential race between Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland and Republican nominee James G. Blaine perhaps reached the zenith in American political lore.

On the morning of July 21, 1884, the Buffalo Evening Telegraph stunned the American public with an exposé, headlined “A Terrible Tale: A Dark Chapter in a Public Man’s History.” The salacious story alleged that Cleveland was the father of an illegitimate 9-year-old child and that he’d been paying the mother for years to keep her quiet.

“Ma, ma, where’s my Pa?” swiftly became a rallying cry for the Republican Party.

The Telegraph wove a sordid tale of paternity and payoffs, detailing Cleveland’s brief one night stand with a 38-year-old widow named Maria Halpin.

Nine months later, Halpin’s son, Oscar Folsom Cleveland, was born and was promptly removed from her custody. Halpin, according to the Smithsonian, “was admitted under murky circumstances to a local asylum for the insane. Doctors from that institution, when interviewed by the press during the 1884 campaign, corroborated Halpin’s insistence that she was not, in fact, in need of committing.”

When asked about Cleveland’s assertion that any number of men could have been Oscar’s father, Halpin was irate: “There is not and never was a doubt as to the paternity of our child, and the attempt of Grover Cleveland or his friends to couple the name of Oscar Folsom or any one else with that of the boy, for that purpose, is simply infamous and false.”

Despite the Telegraph’s story, Cleveland defeated Blain in the poll boxes, and the chant of “Ma, ma, where’s my Pa?” was answered by Democrats: “Gone to the White House, ha ha ha!”

James Garfield

“There are hours when my heart almost breaks with the cruel thought that our marriage is based upon the cold stern word duty,” Lucretia Rudolph wrote on August 19, 1858, expressing her fears about her upcoming nuptials to James Garfield.

And indeed, there was cause for concern. On Nov. 11, 1858, Lucretia and Garfield wed—and if the latter’s diary entry is any indication, with little fanfare and romance.

“Was married to Lucretia Rudolph….” was all Garfield noted of the day.

According to the Library of Congress, separation, “both emotional and physical, characterized the marriage for several years.” After the death of their daughter Trot in December 1863, the distance between the two became even greater, leading Garfield to find “comfort” in the arms of a woman in New York.

Yet this story had a somewhat happy ending—minus the assassination of Garfield in 1881. The affair managed to bring the husband and wife closer, with Garfield later writing in December 1867, “We no longer love because we ought to, but because we do. Were I free to choose out of all the world the sharer of my heart and home and life, I would fly to you and ask you to be mine as you are.”