South Vietnam’s treatment of its largest minority after a 1964 uprising weakened an alliance crucial to defeating the communists

Little good news came out of South Vietnam in the early 1960s. Military reverses in the fight against communist troops, the November 1963 assassination of President Ngo Dinh Diem, coup plotting and inept juntas paralyzed the country’s government. The performance of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN, was lackluster despite increasing numbers of U.S advisers and the influx of modern equipment. One bright light was the recruitment of ethnic minority Montagnards, a French phrase for “mountain people,” into militias supported by U.S Army Special Forces. Together, they protected villages and thwarted attempts by the Viet Cong to expand their control in the Central Highlands.

The alliance between Montagnard tribes and the South Vietnamese government, however, was fraught with upheaval. Among the Montagnard militiamen were dissidents who wanted the tribes to have complete autonomy from the government, and in September 1964 they revolted against the South Vietnamese units in charge of them. Negotiations brought the rebellion to an end after 10 days. But tensions remained, and a strong united force of the ARVN and Montagnards, who had a reputation as tough fighters, never materialized—another missed opportunity during the long war.

U.S. aspirations for a closely woven ARVN-Montagnard force emerged in 1961, when Col. Gilbert B. Layton, an Army officer at the CIA office in Saigon, conducted an in-depth study of the 1946-54 Indochina War that gave Vietnam its independence from France. Layton noted that French colonial administrators cultivated good relations with minorities, about 20 percent of the citizenry. Some indigenous groups saw an alliance with France as a way to nurture their own nationalistic hopes, while others sought protection from their traditional lowland enemies, the Vietnamese.

In 1951, Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, the senior French officer in Indochina, used those affiliations as weapons against the Viet Minh, the organization created by Ho Chi Minh to lead the fight for independence. De Lattre formed French-led guerrilla battalions that established viable insurgencies in territories Ho Chi Minh’s army had considered secure, including the Central Highlands, and were active until the 1954 Geneva peace agreement, which created the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and the Republic of Vietnam in the south.

Using the French experience, U.S. officials believed organizing minorities into self-defense forces would be more effective in controlling South Vietnam’s growing Viet Cong insurgency than forming guerrilla battalions. Those local defense forces were part of a larger counterinsurgency program that became known as “pacification,” a mix of village security, civic improvement projects, economic development and improved governance.

Nearly a million strong, the Montagnards (pronounced mon-ton-yards) were a logical counterforce to the Viet Cong, but their distrust of the Saigon regime threatened to quash any government-related program before it began. It was a resentment that went back centuries.

Montagnard is not the name of one specific ethnic group, but rather is a term used to encompass dozens of distinct tribes living in the mountainous regions stretching from the central part of South Vietnam to the Demilitarized Zone at the border with North Vietnam. Prominent Montagnard tribes included the Rhade, Jarai and Mnong in the Central Highlands. It is believed that the Montagnards, who have no written history, occupied Vietnam’s hill country since the third century after being forced out of the more fertile coastal regions by the Annamese, ethnic Vietnamese who eventually grew into an overwhelming majority.

The Montagnard’s traditional hostility toward the Vietnamese-dominated government increased in 1955 when Diem terminated the semi-autonomous status the tribes enjoyed under the French and brought them under Saigon’s direct rule.

Montagnard grievances were numerous: encroachment on tribal lands; no legislative representation; shabby treatment by local magistrates; refusal to allow their languages to be taught in schools; and promises of aid that never materialized. Government officials regularly referred to them as moi, a pejorative term meaning barbarians or savages.

Two smaller sects, the Cham and Khmers, also had strained ties with the government. The Cham people, whose population was estimated at 35,000 in 1955, were Hindu migrants of ancient origins who inhabited isolated settlements on the coastal plains near Phan Rang, 160 miles north of Saigon. Large enclaves of Khmers, 400,000 native Cambodians, lived in the western border regions. The Khmers did not consider their lands part of Vietnam, so the government treated them as troublemakers. The Cham were simply ignored.

The CIA, however, believed that Yankee ingenuity would bridge the abyss separating the ethnic minorities and South Vietnamese officials. It decided to start with Rhade villages.

About 100,000 Rhade were concentrated near Ban Me Thuot, the Central Highlands capital of Darlac province. The Rhade lived in small villages where they subsisted on hunting and “slash and burn” farming, cutting and burning forestland to create fields. When the land was no longer productive, they moved on.

U.S. Ambassador Frederick Nolting gained approval in 1961 to organize selected Rhade villages into self-defense forces. The agreement signed by one of Diem’s ministers stated the program would be administered by the CIA, separate from the ARVN and the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group created in 1955 to oversee improvement of the South Vietnamese army. That setup generated hostility from the outset because CIA operatives would be overseeing armed troops, albeit paramilitary forces, an arrangement that did not sit well with the military advisory group’s commander.

The CIA selected Buon Enao, a village of 400 just east of Ban Me Thuot, as a test site. In mid-1961 the agency approached Rhade tribal elders with a proposal: If they pledged fealty to the Saigon government, the United States would provide weapons, organize village defenses and bring in Special Forces medics to offer basic health care. American zeal and a genuine concern for the villagers overcame the Rhade’s initial negativity, rooted in a deep mistrust of the South Vietnamese government. The test program flourished, and word spread. Soon nearby villages also joined what was called the Village Defense Program and later became the Civilian Irregular Defense Group, essentially U.S. armed and trained militias.

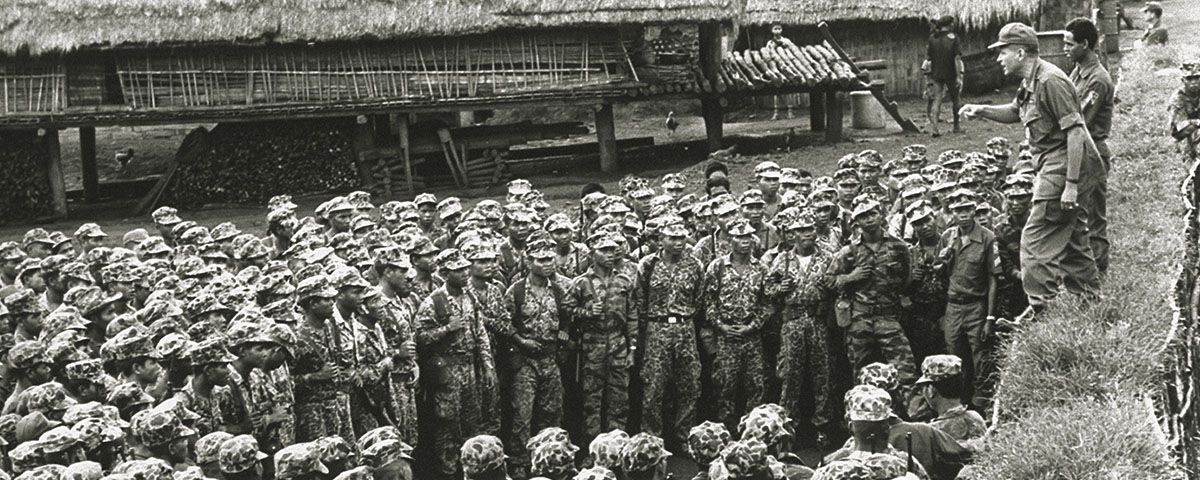

By early 1962, about 14,000 people resided in 40 protected villages. Those settlements were defended by 1,300 trained militiamen. About 1,000 were local security personnel, apportioned among the 40 villages based on size and location. The other 300 were organized into three Mobile Strike Force companies (dubbed Mike Forces or strikers), consisting of exceptionally well-trained men available to quickly reinforce villages under attack. Each of the three approximately 100-man striker companies was responsible for villages in an assigned sector.

As the Civilian Irregular Defense Group program grew, U.S. Special Forces troops became more involved with the CIA operation. The CIDG expansion was led by Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha, an “A Team,” normally consisting of 12 soldiers led by a captain. The first detachment of Green Berets, configured to eight men, was ordered to South Vietnam in February 1962. Capt. Ronald A. Shackleton and seven noncommissioned officers from the 1st Special Forces Group on Okinawa, Japan, were joined by 10 members of the Vietnamese Special Forces, Luc Luong Dac Biet. The 10 LLDB soldiers were of Rhade ancestry, a rarity in an organization that normally barred Montagnard enlistment.

The Americans served only as advisers, in accordance with the U.S. policy of assisting, not commanding. Within six months, more than 200 Darlac villages were protected by 10,000 defenders and 1,500 strikers. The province was declared secure, and a delighted Diem requested similar training for neighboring Jarai and Mnong tribes. Unfortunately, there were no more Rhade men in the LLDB to support the CIDG expansion with South Vietnamese units that included Montagnards.

Coinciding with the arrival of Shackleton’s team, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, was established in February 1962 to oversee the dramatically increasing number of advisers and logistics support for the ARVN. The Military Assistance Advisory Group was integrated into the new MACV headquarters.

The success in Darlac opened a flood gate of money and equipment flowing from Washington to the CIDG program. National Security Action Memorandum 57, published in the summer of 1962, transferred all Special Forces activities from the CIA to MACV, and before long A Teams spread from Khe Sanh near the DMZ to the southernmost tip of the Mekong Delta.

But nothing was simple or easy. In 1962 the LLDB was not part of South Vietnam’s army. It was under the separate command of Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu. His LLDB troops were much more adept at subduing anti-government rallies and raiding political opponents’ homes than in leading soldiers in battles with the VC. They gravitated toward the “creature comforts” of the cities, while the Americans embraced the living standards and the hardships of the Montagnard forces. Age-old enmities between Montagnards and Vietnamese were exacerbated by the blatant racism of some LLDB troops.

Consequently, CIDG soldiers turned to their U.S. advisers for support. With their “can do” and “get it done now” mentality, the Americans sometimes became the de facto leaders. Village defenders and strikers knew their pay, equipment and clinics came from the Americans. They gave their loyalty to their Western benefactors—who reciprocated the feeling. That relationship caused a variety of fissures. The LLDB saw the Montagnard soldiers as disloyal. The South Vietnamese government believed U.S. Special Forces teams were forging ties that encouraged separatist movements. And MACV was concerned that Special Forces officers were often commanding the CIDG, a direct contravention of their charter to only advise.

All the good work almost came to naught on Nov. 1, 1963, when Diem and his brother were assassinated in a coup led by Maj. Gen. Duong Van Minh. The junta wasted no time in bringing the LLBD into the South Vietnamese army and taking direct charge of all paramilitary units. The transition was made in great haste, and conflicting instructions caused confusion.

Complicating the coup disequilibrium was the release of political prisoners, including some who had organized a Montagnard independence movement that became the United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races, called FULRO, from the French phrase, Front Unifié la Libération des Races Opprimées. Return of these committed activists resuscitated the quest for sovereignty and renewed agitation among the Rhade.

Turmoil increased when Maj. Gen. Nguyen Khanh seized power from Minh in a bloodless takeover on Jan. 30, 1964. Khanh issued a flurry of directives to the CIDG forces, changing their mission from pacification to combat operations.

The Montagnard militias, whose training had been defensive in nature, were ill-prepared for offensive missions. That whiplash change also took men away from their villages, limited the numbers available for protecting homes and increased the presence of overbearing LLDB officers. Additionally, Khanh’s government did not follow through on promises Diem and Minh had made to the Montagnards. Supplies earmarked for villagers were skimmed off by corrupt provincial administrators. The U.S. Special Forces logistical system offset the shortfalls but could not transform government attitudes nor placate the CDIG troops.

All elements of dissatisfaction came to a head on the night of Sept. 19-20, 1964. In a carefully orchestrated operation, the Montagnards in five CIDG camps attacked the LLDB and local authorities. Each mutinous camp raised the FULRO flag in an act of defiance.

At Bon Sar Pa, about 25 miles west of provincial capital Ban Me Thuot, three companies of Rhade tribesmen killed 11 LLDB soldiers, took 200 hostages, left them at the camp under heavy guard and boarded trucks headed to the capital, where they planned to link up with other rebels in a coordinated attack on the city. The A-Team commander, Capt. Charles Darnell, tried unsuccessfully to stop them.

More violence occurred at Bu Prang Camp in adjacent Quang Duc province, where 15 LLDB troops were killed and numerous civilians murdered. The Bu Prang rebels planned to seize the provincial capital, Gia Nghia, but were stymied by a lack of vehicles. Instead, they stayed near their camp. The mutiny therefore was confined to Darlac province and centered on Ban Me Thuot.

At the Buon Mi Ga camp, 10 LLDB soldiers were killed, and CIDG troops then moved toward Ban Me Thuot on a mission to seize the radio station and airfield. The U.S. Special Forces personnel at the camp were left alone, and after the CIDG companies departed, helicopters evacuated the Americans.

In another camp, LLDB officers at Ban Don were bound and gagged but otherwise unharmed before several hundred Montagnard began a foot march toward Ban Me Thuot. The Special Forces commander at Ban Don, Capt. Curtis Terry, commandeered a jeep, caught up with the marching column of mutineers and persuaded the men to return to the camp. Terry’s coolness under pressure resulted in the release of the LLDB troops and a degree of normalcy at Ban Don.

The CIDG at Buon Brieng joined in the melee but stopped short of leaving the camp when Capt. Vernon P. Gillespie, the A Team commander, barred the way. His courage and rapport with the CIDG militiamen persuaded them that nothing good would come of joining the rebellion. Gillespie’s peacemaking skills also kept open the main north-south road leading to Ban Me Thuot, Highway 14, allowing additional ARVN units to reinforce the Ban Me Thuot garrison.

The killings could have been far worse and Ban Me Thuot might have fallen had Special Forces detachments in other camps not persuaded the CIDG troops to return to their barracks. When those units failed to show up at Ban Me Thuot, the rebellion’s leaders decided there were insufficient numbers to mount a decisive attack on Darlac’s capital.

News of the revolt reached MACV headquarters the next morning, Sept. 20. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. troops in South Vietnam, feared that battles between the ARVN and Montagnards might spark a countrywide insurrection that could break apart the South Vietnamese government. Tensions were still high after the Aug. 2 North Vietnamese attack on a U.S. Navy destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin. Earlier in September a failed coup attempt in Saigon had destabilized Khanh’s government.

Westmoreland dispatched Brig. Gen. William E. DePuy, MACV director of operations, to help restore order. Meeting with Khanh’s emissaries, DePuy counseled restraint and asked for time to allow negotiations with the Montagnards. He carried a letter from Westmoreland expressing strong support for Khanh and a threat to cut off pay and supplies to rebellious CIDG units.

There was only one other incident of open fighting. On the night of Sept. 20, strikers from Buon Mi Ga attacked a 23rd ARVN Division roadblock just east of Ban Me Thuot, but they were repulsed after suffering 10 killed. Subsequent indecision on the part of the Montagnards allowed time for talks to begin—and allowed the Rhade leader of FULRO, who called himself Y Bham, to escape and re-establish his movement in Cambodia.

Col. John F. “Fritz” Freund, the MACV deputy adviser for the Central Highlands region, was the first senior American officer to arrive in Ban Me Thuot and became a key player in bringing the rebellion under control. Freund, a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, had a distinguished record as an artilleryman in World War II. Fluency in French and a flair for melodrama enhanced his stature. French was more common than English in the CIDG forces, and the tribesmen always enjoyed a little panache.

When Freund met with the rebels holding 200 Vietnamese hostages at Bon Sar Pa, he was accompanied by Darnell, the respected A Team commander who knew many of them. While the Americans were negotiating peace with the Montagnards, an ARVN regiment was en route to free the hostages by force. Fortunately, Freund and Darnell persuaded the rebel leaders to release the prisoners, in large part because of a flamboyant speech the colonel gave in French.

Later, Freund claimed that he challenged the leader of the Bon Sar Pa rebels to personally shoot him rather than harm the hostages. Although never verified, the incident became part of Freund’s mystique, one that he frequently cited. Like most war stories, the tale got better with retelling.

At the same time, Khanh agreed to amnesty for all participants and offered to sponsor a conference with Montagnard leaders to address minority issues. This satisfied the CIDG troops, and by Sept. 28 all of them were back in their camps and the mutineer banners were replaced by South Vietnamese flags. However, troublesome fallout soon followed.

Maj. Gen. Nguyen Huu Co, ARVN commander in the 12 provinces of central South Vietnam, was infuriated that Americans, not Vietnamese, were the key intermediaries in defusing the crisis. He perceived Freund’s and Darnell’s visible roles in resolving the Bon Sar Pa standoff as a “loss of face.” Meanwhile, senior Americans in Saigon—including the U.S. ambassador, retired Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor—viewed the Special Forces officers involved in quelling the revolt as advocates for the CIDG units and, at times, their real leaders. Westmoreland, never comfortable with unconventional operators, instructed the top Special Forces commander, Col. John H. Spears, to limit his teams’ activities to advice and assistance and to uphold the LLDB’s authority. Nothing in his guidance was left to interpretation.

An uneasy truce ensued. During a late October conference at Pleiku in the Central Highlands, Montagnard delegates presented commander Co with a long list of grievances. Some minor requests were approved. Others, the most important dealing with ownership of land and restoration of tribal courts, were sent to a committee for further study. But nothing happened.

The camp at Bon Sar Pa, believed to be the epicenter of the dissent, and other camps involved in the revolt were closed and their CIDG garrisons dissolved. This swift action flew in the face of the promise of amnesty. Government duplicity was viewed as being alive and well in the Central Highlands.

When widely publicized concessions were not implemented, incidents of open rebellion flared again in the highlands. Uprisings in September and December of 1965 were ruthlessly suppressed, and the Saigon government never made a serious attempt to assimilate minorities into national life.

Discontent among the Montagnards would continue throughout the war. Strong ties with U.S. Special Forces remained, but those were severed when the CIDG program was terminated and the striker companies were integrated into ARVN units during the final stages of “Vietnamization,” the transfer of all military operations to the South Vietnamese as the Americans began their withdrawal in 1969.

When the 5th Special Forces Group departed in March 1971, the former CIDG troops were at the mercy of the Vietnamese, their historical enemies. After the North Vietnamese took over on April 30, 1975, the Montagnards hoped the new regime—even though communist—might usher in a better era. But the highland tribes suffered even more. Their lands were colonized into New Economic Zones, villages were burned, families were forcibly resettled, and local customs were suppressed. There were credible reports that nearly 200,000 Montagnards were killed during those postwar decades. Regardless of the number, it was a tragic end for a community that just wanted to be left alone.

—John D. Howard served in the U.S. Army for 28 years, retiring as a brigadier general. During his first Vietnam tour with the 101st Airborne Division (1965-1966), his platoon conducted operations with CIDG strikers.

This article was published in the April 2019 issue of Vietnam.