Al Swearengen is the vile-tempered proprietor of the Gem Theater, an entertainment hotspot where drink, sex and gambling are served up like flapjacks in an all-night greasy spoon. Seth Bullock is the Canadian hardware entrepreneur who journeys west and becomes a sheriff in a lawless mining camp. Solomon (‘Sol’) Star, Bullock’s unassuming partner, is the voice of reason when trouble erupts. Charlie Utter, plainsman, scout and merchant, is sidekick to the legendary Wild Bill Hickok. E.B. Farnum, owner of the Grand Central Hotel, is never averse to a scheme, legitimate or otherwise, that will earn him a quick dollar. The Reverend Henry Weston Smith cares for plague victims and officiates at town funerals, and sadly is driven to dementia by a brain tumor. Dan Dority and Johnny Burns manage the saloon at the Gem and keep Swearengen’s working girls in line.

Many Wild West readers will recognize these characters from the electrifying HBO (Home Box Office) television series Deadwood. The cast of regulars in the second season (which became available on DVD in May 2006) includes Ian McShane as Swearengen, Timothy Olyphant as Bullock, John Hawkes as Star, Dayton Callie as Utter, William Sanderson as Farnum, W. Earl Brown as Dority and Sean Bridgers as Burns. These characters were all flesh-and-blood folks who inhabited the real Dakota Territory (present-day South Dakota) town of Deadwood during the Black Hills gold rush. Aficionados of the HBO drama, now in its third season, may find it hard to believe that the true accounts of these men’s lives sometimes rival those played out on the screen. Nonetheless, their stories, packed with daring, determination, greed and treachery, transcend legend and anchor them in Deadwood’s history.

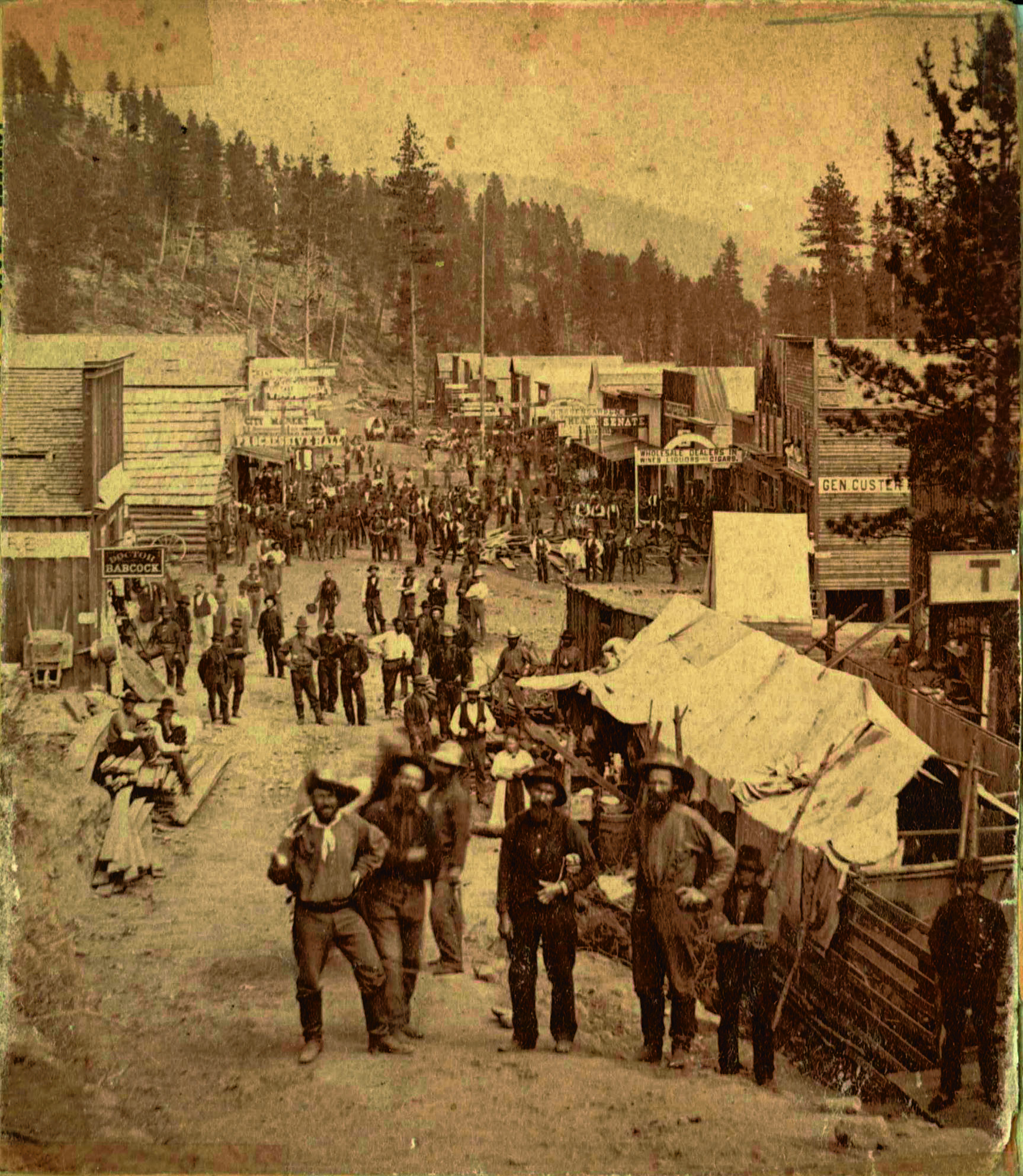

Deadwood grew from the promise of wealth. During the summer of 1874, a band of U.S. cavalrymen led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer discovered traces of gold in the Black Hills. Custer encouraged exploration there, although the Black Hills belonged to the Sioux Reservation and were off-limits to white civilians. Government officials could do little to stop the rapid influx of fortune seekers, and eventually they stopped trying. Between 1874 and 1877, some 20,000 prospectors made the trek to Deadwood Gulch. In 1875 the fledgling settlement — Deadwood City became the commercial district in the gulch — was given its official name, when a tract of surrounding pine forest was destroyed by fire. Deadwood didn’t have an organized government until October 1876.

In its earliest days Deadwood was little more than a rough-and-tumble mining camp, where men, livestock and the elements coexisted, in a sprawl of ramshackle buildings and tents, knee-deep in mud, rats and garbage. Because the town was located illegally on Indian land, no government or law existed to keep trouble in check. Most of the town’s residents frequented the saloons and brothels that sprang up on nearly every street, occupying their time with drinking, gambling and fighting. Violence was common, lending credence to the oft-repeated observation that Deadwood hosted a murder a day. Nonetheless, over time the town obtained a measure of respectability as merchants and other professional men took up residence, established businesses and hammered out the first vestiges of government. By the end of 1876, Deadwood had more than 3,000 residents and nearly 200 businesses.

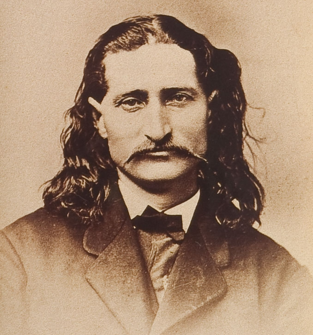

Two of Deadwood’s most famous characters, if not illustrious citizens, were Martha Calamity Jane Canary and Wild Bill Hickok. Naturally, they have made appearances in the HBO series. Hickok, true to life, died during the first season; Keith Carradine portrayed him. Although Calamity Jane was known to dress like a man and swear like a muleskinner in real life, she (played by Robin Weigert in Deadwood) only sometimes resembled a real man. She was a woman of contradiction—one who reportedly nursed the sick during a smallpox epidemic, drank most anytime and worked as a prostitute in several of Deadwood’s brothels. Although her relationship with Hickok has been blown out of proportion, she did pose in front of his grave in Deadwood’s Mount Moriah Cemetery about a month before her death in 1903 at age 47, and she allegedly requested that she be buried beside Hickok’s remains.

Wild Bill Hickok was one of the West’s real men—a sharp-dressing sharpshooter who could be both tough and tender. It is said he may have killed as many as 36 men, but more likely his total was less than 10. In any case, he became legendary in his own time, mostly for his deeds as a peace officer, even if he was generally more interested in gambling than enforcing the law. His place in Deadwood’s history, of course, stems from the fact that he was last seen alive in a local establishment, the Lewis and Mann No. 10 Saloon. On August 2, 1876, Hickok was immersed in a hand of poker when a lowlife named Jack McCall shot him in the back of the head. Wild Bill’s name and his final poker hand (Dead Man’s Hand, featuring aces and eights) have lived on in the annals of the West. Hickok was first buried at Deadwood’s Ingleside Cemetery, and then in 1879 his remains were reburied at Mount Moriah Cemetery. That a man of Hickok’s reputation was shot down in Deadwood certainly added to the town’s reputation for lawlessness. Still, like the other communities that survived in the West, Deadwood was eventually tamed.

Many men were responsible for transforming Deadwood from a lawless frontier settlement to a prosperous mining town, but no one was more instrumental in the taming than Seth Bullock. Estelline Bennett, daughter of federal Judge Granville G. Bennett and author of the memoir Old Deadwood Days, recalled the words of a local railroad official: It was the Bennetts and Bullocks that brought law and order into the Black Hills.

Seth Bullock was born in Ontario, Canada, in 1847, the son of a British military officer. At odds with his strict father, Bullock left home at age 18 for Montana Territory, where he was drawn to politics and was elected state senator in 1871. In the summer of 1876, Bullock and his longtime friend Sol Star went looking for opportunity. After a harrowing monthlong wagon trek (during which their horses bolted, dumping them and their belongings into a stream), the pair arrived in Deadwood on August 1, where they wasted no time appraising the needs of the sprawling camp. Soon they were peddling tools, china, mining gear, cigars, tea and chamber pots to the town’s residents, from a building the partners constructed at the corner of Main and Wall streets.

Less than a day after Bullock and Star arrived in the goldcamp, McCall shot Wild Bill Hickok to death in the No. 10 Saloon. The next morning, an impromptu court of prospectors acquitted McCall, an apparent move to ensure that Deadwood remained lawless. At the same time, Indians were massing in the Black Hills in preparation for an attack on the settlement. The escalating violence did not sit well with Bullock’s decorous sensibility, and the sight of a Mexican bandit riding through the streets brandishing a severed Indian head just hours after Hickok’s murder was enough to convince Bullock to address the town’s crucial need for law and order. By the end of the month he had become de facto sheriff of the camp. When Lawrence County was formed in April 1877, Bullock became its first sheriff, appointed by territorial Governor John L. Pennington.

Bullock established a reputation as a tough but fair lawman. In contrast to the trigger-happy outlaws he policed, Bullock rarely used a gun. Tall and charismatic, the sheriff was able to maintain order through quick thinking and the sheer force of his personality. Bullock’s grandson once said of him: He could outstare a mad cobra or a rogue elephant.

During his tenure as sheriff, Bullock settled disputes over mining claims; rounded up horse thieves, road agents and stagecoach robbers; investigated murders; presided over trials; oversaw the transport and lodging of prisoners; organized militias to combat Indian attacks; and broke up countless fistfights. Bullock was concerned about the reputation of Deadwood, and thus diligent in his efforts to regulate gambling and prostitution. He had numerous run-ins with Al Swearengen, proprietor of the notorious Gem Theater, and reportedly drew a line across Main Street, separating the respectable areas of Deadwood from the seedier neighborhoods, or Badlands, controlled by Swearengen.

Bullock, who served as sheriff into 1878 and then continued to uphold the law as a deputy U.S. marshal for a time, had little tolerance for disruption of the public peace, and once crushed a mining strike by dumping canisters of sulfurous gas into the Keets Mine, where the boycotting miners were entrenched. Not a single shot was fired as the humbled miners emerged from the mining shaft, choking and bleary-eyed.

Bullock helped establish the Deadwood Board of Health and Street Commissioners, which authorized the building of a pest house for the care of smallpox victims, issued sanitation and fire safety codes, set up police and fire departments and founded the town’s first cemetery. He did not limit his formidable will and intellect to law enforcement and civic matters. He was an ardent conservationist who understood the necessity of preserving the wilderness. In 1872, while serving as senator in Montana Territory, he drafted the Yellowstone Act, which paved the way for the creation of Yellowstone National Park. Bullock is credited with planting the region’s first alfalfa crop, now a mainstay of South Dakota agriculture. He raised cattle and Thoroughbred horses, experimented with irrigation and established the area’s first fish hatchery. The introduction of rail service to the Black Hills in 1890 made the region one of the country’s busiest livestock shipping centers, and its arrival was attributed to Bullock’s tireless negotiation with the Fremont, Elkhorn & Missouri Valley Railroad.

In 1894, Bullock spent $40,000 to build the Bullock Hotel, a three-story 64-room lodging with steam heat and indoor plumbing. The hotel, which operates today and is one of Deadwood’s most popular tourist attractions, was known for its luxurious accommodations and fine dining.

Bullock became a confidant to Theodore Roosevelt, whom he met while patrolling the range in 1884. Roosevelt, a deputy sheriff from northern Dakota, had just captured a horse thief, Crazy Steve, whom Bullock was also pursuing. From that moment on, the two were fast friends. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt appointed Bullock leader of the Black Hills Rough Riders, earning him the lifelong nickname of captain. When Roosevelt was re-elected president in 1904, Bullock and 50 cowboys, including the legendary Tom Mix, marched in the inaugural parade. In 1905 Roosevelt appointed Bullock U.S. marshal for South Dakota. It was dangerous work; during Bullock’s 10 years in office, more than a dozen other marshals were killed in the line of duty. Roosevelt acknowledged Bullock’s courage and integrity by renaming Scruton Peak, in the Black Hills, Seth Bullock Lookout, and describing his friend as the ideal American.

A devoted family man, Bullock married his childhood sweetheart, Martha Eccles, in 1874. She was an accomplished musician and president of the Round Table Club, Deadwood’s literary society. The couple lived at a ranch outside of town in the Belle Fourche Valley, where they raised two daughters, Florence and Margaret, and a son, Stanley, and also cared for Bullock’s orphaned nephew.

Bullock wrote of his early experiences in the Black Hills in The Founding of a County, published in 1876. The book provides a fascinating glimpse of life in early Deadwood, as well as an insight into the determination, courage and vision of its author. Bullock died of cancer on September 23, 1919, at age 70, at the Bullock Hotel, and was buried near a trail he loved in Mount Moriah Cemetery. According to local lore, the ghost of Seth Bullock roams the hallways of the hotel.

Sol Star is remembered as Bullock’s business partner and right-hand man. However, he was accomplished in his own right: a respected and beloved public servant, politician and entrepreneur who helped bring civility and prosperity to early Deadwood.

Born in Bavaria in 1840, Star was 10 years old when he was sent to live with his uncle, Abraham Frielander, a garment merchant in Ohio. After working in his uncle’s business and finishing his schooling, Star traveled to Montana Territory, where he met and began a lifelong friendship with Bullock.

Bullock and Star were astute business partners who invested in agriculture and cattle ranching. In 1880 they joined forces with businessman Harris Franklin to establish the town’s first grain mill, the Deadwood Flouring Mill Co. Star served as general manager of the mill, overseeing its daily operation with a perfectionist’s eye. He even took to naming the types of flours they produced; a customer favorite was SSS, or Senator Sol Star, a sly reference to Star’s political aspirations.

Between 1877 and 1917, Star served as Deadwood’s mayor, postmaster and town councilman, as well as state auditor, county clerk of courts and chairman of the first state Republican convention. He held the office of mayor for five terms, prompting a local tobacco producer to name a cigar after him. Unfortunately, a scandal involving misappropriation of government money while he was serving as postmaster marred his reputation and forced him to resign. Although Star was ultimately acquitted of any wrongdoing, the incident troubled him, and he worked hard to restore his image as an honest public servant.

Star was also an officer of the Masonic Temple, a Knight of Pythias (a group devoted to peace) and a member of both the Order of Red Men and the Ancient Order of United Workmen, organizations that espoused the principles of American liberty and equality for all workingmen. A prominent member of Deadwood’s large Jewish community, Star was active in the local synagogue and gave generously to needy Jewish families in Russia and Europe. He worked hard to win the trust of the town’s Chinese residents, at a time when nonwhites were viewed as second-class citizens. Moved by the plight of the town’s downtrodden prostitutes, Star often tried to come to their aid.

Although it is reported that Star made at least one trip back East in search of a wife, he never married, and lived alone at his ranch until his death in 1917. His funeral was reportedly the largest and most extravagant ever held in Deadwood. Star’s body was transported to St. Louis, where he was laid to rest in Mount Sinai Cemetery. Colorado Charlie Utter was among the most intriguing men in Deadwood history. A rugged frontiersman with an eye for fine attire, he was at ease tracking wild game alone in the wilderness or placing bets at a crowded poker table.

Born in New York in 1838, Utter spent most of his boyhood on his father’s farm in Illinois. Sometime around 1858 Utter went west with his brother Steve, and the pair explored the mountains of what would become Colorado. Taken with the beauty and abundant wildlife of an area known as North Park, Colorado Charlie settled there, building a cabin on the Troublesome River. The region was home to the Ute Indians, whom Utter befriended. He was most likely the only white man living in the area at the time.

Utter wore many hats in his working life. When gold rush fever moved through the area, he became a prospector, filing more than 60 mining claims. In 1861 (when Colorado Territory was formed) he was appointed the recorder of mining claims in the region, a position that made him responsible for monitoring all claims, and entitled him to collect and keep filing fees. During this time he also acted as an assistant translator for the Office of Indian Affairs, and began to assemble a herd of horses and pack mules, with an eye toward establishing the area’s first freight service. By 1867 Charlie Utter’s Mule Pack Train was advertised in the Colorado Miner as an efficient means of hauling both ore and people through the mountains, offering service from the towns of Georgetown, Central and Brownville. Utter displayed a knack for engineering when he devised a means of using his mule train to transport a 3-mile-long wire cable needed for the construction of an aerial tramway up 15 miles of mountain range. Utter also earned a handsome living as a fur trapper and hunter.

In 1866 Utter married Tilly Nash, the 15-year-old daughter of a baker from nearby Empire. No doubt his striking appearance worked to his advantage in attracting a bride. Although short, Utter was boyishly handsome and exuded charisma. Obsessed with cleanliness, he indulged in a daily bath at a time when personal hygiene was nearly unknown among frontiersmen. Each morning Utter spent an hour in the local barber shop, having his cascading blonde hair washed and curled, and was probably the only man in Colorado to own a mirror and set of brushes and combs. In contrast to the drab and dirty clothing worn by miners, Utter favored the flamboyant garb of a trapper; hand-stitched leggings trimmed with fringe and otter fur, elaborate beaded moccasins and a deerskin vest with bear claws for buttons. His pistols were inlaid with pearl and gold and inscribed with his name. In later years Utter often traded his frontier attire for tailored overcoats, silk shirts and top hats, and he sported a gold watch studded with diamonds and rubies. He was, in the words of an admiring observer, a figure well worth looking at.

Utter sensed that the Black Hills would be the site of the next gold rush (a real lallapaloozer is how he put it), and in the spring of 1876 he and his wife and brother headed a wagon train bound for Deadwood. More than 100 people made the trek, including a large contingent of prostitutes.

Upon his arrival in the town, Utter reestablished his freight service, and also began the operation of a Pony Express-like operation, delivering mail between Deadwood and Fort Laramie, in Wyoming Territory, in 48 hours, at a charge of 25 cents per letter. At peak capacity, the service was delivering 5,000 letters a trip. Although regarded as an upstanding citizen, Utter still occasionally ran afoul of the law. In 1879 he opened a dance hall in the nearby town of Lead. The boisterous music and scandalous cancan dancing that erupted from the nuisance dance hall prompted a local judge to fine Utter $50 for disturbing the peace.

It is not known how Charlie Utter met his pard, Wild Bill Hickok. It is possible that the two crossed paths in 1854-55 in Kansas, where Hickok was working as a bodyguard for a local politician. Utter was fiercely protective of Wild Bill and tried unsuccessfully to dissuade the famed gunslinger from his cavalier drinking and gambling. When Hickok was gunned down in August 1876, Utter organized and paid for his funeral, and mailed a lock of Hickok’s hair to his widow, Agnes Lake.

After Utter and Tilly separated in 1880, he may have moved to Socorro, New Mexico Territory, where he reportedly ran a saloon and gambling hall, and fell in love with a beautiful faro dealer named Minnie Fowler. Upton Lorentz, a friend of Utter’s, maintained that Utter settled in Panama sometime around 1888, where he operated a pharmacy, practiced medicine among the local Indians and even delivered babies. Lorentz told the Frontier Times that he last saw Utter, blind and grizzled, sitting in a rocking chair in front of his pharmacy in 1910. The details of Utter’s final days are unknown.

Today Charlie Utter is best remembered as the devoted friend who inscribed this touching epitaph on Wild Bill’s tombstone:

Pard, we will meet again in the Happy

COLORADO CHARLIE, C.H. UTTER

Hunting Ground. To part no more, Goodbye.

Al Swearengen was a real man of a different sort. His influence on daily life in Deadwood was profound. By all accounts he was a ruthless businessman, feared and hated by many.

Ellis Alfred Swearengen and his twin brother, Samuel, were born in 1845 in the town of Oskaloosa in Mahaska County, Iowa. Their father, Daniel, earned his living as a farmer and butcher, while the boys’ mother, Keziah Montgomery Swearengen, tended to the couple’s large brood, which included either six or seven other children. When Keziah died in 1879, Daniel married Arienta Morrisson, a woman 20 years his junior, and moved to Yankton, Dakota Territory.

Al Swearengen left Iowa around 1870 and settled in Deadwood with his first wife, Nettie, and his brother Winfield sometime afterward. By 1876 Swearengen had already separated from Nettie, who had accused him of abuse. At the time he was managing the Cricket Saloon, where he booked prizefights that went 52 rounds and often provoked fisticuffs among audience members.

In April 1877, Swearengen opened his infamous Gem Theater, which also served as a dance hall, saloon and more. Swearengen outfitted his new establishment with lavish decor and traveled as far as Chicago in search of exotic entertainment. Over the next decade, singers, dancers, comedians, contortionists, trapeze artists and child actors thrilled the Gem’s audiences. Swearengen even staged reenactments of tribal war dances, performed by groups of Sioux Indians wearing war paint and headdresses. The Gem, however, came to be known for activity of a more illicit nature. Swearengen enlisted young women to work as dancers and singers in his theater. Unbeknown to the star-struck ladies who journeyed from as far as the East Coast to seek employment at the Gem, Swearengen’s true intention for his new hires was a sinister one. Forced to work as prostitutes, the women recruited by Swearengen were routinely beaten, humiliated and dosed with the opioid laudanum. Many of his victims were underage girls who did not speak English. Under Swearengen’s iron-fisted rule, the girls plied their trade in curtained cubicles called cribs surrounding the Gem’s stage, and lived in small rooms on the theater’s second floor. As a young girl, Estelline Bennett recalled asking an elder if she could go to the Gem to see a performance. The rebuff was stern: “Nice people like us don’t go to the Gem Theater.”

The Gem’s mix of dancing, drinking, sex and gambling proved to be a winning hand for Swearengen, grossing more than $5,000 a night. Not surprisingly, it was also the cause of frequent trouble. Swearengen was arrested numerous times for assault and battery (on staff and patrons alike), disturbing the peace and nonpayment of taxes. In 1878 Sheriff Seth Bullock shuttered the Gem for 48 hours, ordering that it be auctioned as payment for debt; when no one dared to bid against Swearengen, he retained ownership of his theater.

In September 1879, a massive fire swept through Deadwood, burning the Gem to the ground. Swearengen had recently spent considerable money remodeling his theater; nonetheless he spared no time or expense rebuilding, installing his own water hydrant to defend against future fire. The Gem reopened less than a month later, the beams of the unfinished roof draped with a huge tent.

Although the Gem was a rousing success, Swearengen’s theater also made him many enemies. In 1892 members of the Methodist Church, offended by the theater’s disreputable activities, rallied unsuccessfully to have the Gem closed. Neighbors complained constantly about the noise, in a number of instances requesting that the Gem employ men who have some knowledge of music. In 1894 Swearengen survived a second Main Street fire. His personal life was equally chaotic. Married twice more, both marriages ended in divorce with charges of spousal abuse and infidelity.

Perhaps fate could not forgive Swearengen’s misdeeds. In 1899 the Gem was once again destroyed by fire. Mired in debt and abandoned by many of his top entertainers, Swearengen was unable to rebuild his beloved theater. Destitute and alone, he was killed in Denver while attempting to jump a train.

Any discussion of Swearengen’s life would be remiss without mention of the havoc he wreaked upon the lives of his working girls. Many of these soiled doves died early, painful deaths as a result of drug addiction, abuse, disease or suicide. Estelline Bennett’s sad recollection of a teenage prostitute who shot herself in her room at the Gem Theater testifies to Swearengen’s infamous legacy: “She was only a few years older than I—girl who should have been in high school, walking with her best friend at recess, and going to church with her family on Sunday. I couldn’t forget her.”

E.B. Farnum, the Reverend Henry Smith, Dan Dority and Johnny Burns are lesser characters on Deadwood, and not too much is known about their real lives. Farnum was a successful Deadwood businessman and investor, as well as a judge who sentenced many horse thieves and cattle rustlers to hanging. On the HBO drama, Preacher Smith suffers from a brain tumor and is smothered by Swearengen; in real life, however, he was probably murdered by Indians while walking to a neighboring camp to deliver a sermon. Less is known about Dority and Burns. Most likely both men worked as bartenders and managers for Swearengen during the Gem Theater’s heyday. Other real-life personalities have shown up in the third season, such as George Hearst, a nearly illiterate mining tycoon who fathered the future newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst.

Thanks to the seamless craft of Deadwood producer and writer David Milch, the men of Deadwood live once again. Sol Star checks his inventory and readies the hardware store for another day’s customers. Outside on the street, Sheriff Bullock warns a peddler hawking locks of Indian hair to stay away from reputable merchants. Over at the blacksmith shop, Charlie Utter outfits his horse for a trek across the mountains. Back at the Gem, Al Swearengen pours himself another cup of coffee and peruses the latest edition of the Pioneer.

Perhaps Misters Star, Bullock, Utter and Swearengen—possibly Wild Bill Hickok, too—would be puzzled by their newfound celebrity, and find our interest in their gritty lives baffling. Under different circumstances perhaps, they might have faded into obscurity and remained strangers to us, like many other men of the Wild West. But one fact is undeniable: Deadwood would have been a very different place without them.