In World War II, the U.S. Army’s 79th Infantry Division slugged its way through one Nazi stronghold after another

At the end of World War I, the U.S. Army directed its various divisions to pick a distinctive shoulder patch (formally known as a shoulder sleeve insignia) that reflected the unit’s history. The relatively new 79th Infantry Division chose the blue-and-white Cross of Lorraine, a well-known two-barred cross that dates back to the 12th century in Europe. Ever since René II, the Duke of Lorraine, had placed the cross on his flag before winning the Battle of Nancy in 1477, it had been the symbol of the often-disputed region of northeastern France. After France lost the province to Germany in 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, the Cross of Lorraine became a symbol of France’s never-ending determination to reclaim the lost territory.

During the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1917, the 79th Division spearheaded the American Expeditionary Forces’ assault on the German-held strongpoint at Montfaucon (Mount Falcon), the strategic key to the vital Meuse-Argonne sector of the Western Front. So strong were Montfaucon’s defenses that the Germans boastfully called it their “Little Gibraltar.” French generals said it would take three months to break the enemy line there. It took the untried, undertrained 79th Division just two days to take Montfaucon, at a cost of 1,200 men. The new shoulder patch, a white Cross of Lorraine on a deep-blue background, honored the division’s sacrifice.

A quarter of a century later, a newly reconstituted 79th Division would return to France to help that nation once again win back the territories it had lost to Germany—this time from the Nazi forces of Adolf Hitler. And its famous shoulder patch would stand for much more than the men in the 79th Division: the Free French forces under exiled general Charles de Gaulle and the underground Resistance forces inside occupied France would adopt the Cross of Lorraine as their symbol as well. Resistance leader Jean Moulin was wearing a scarf bearing the cross when he was captured and later tortured to death by Gestapo commander Nicolas (Klaus) Barbie—the infamous “Butcher of Lyon”—in 1943.

Few if any of the American servicemen and draftees in the 79th Division were aware of Moulin’s ultimate sacrifice when they joined the division, but they were all keenly aware of the difficult task they and other Allied forces faced in liberating France and the rest of Europe from the Nazis, much as the first 79th Division had done at Montfaucon in 1918. It would be an unwelcome but necessary homecoming.

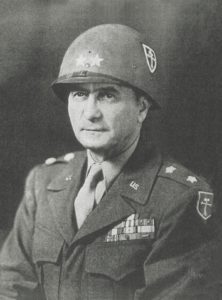

The 79th Division was reactivated on June 15, 1942, at Camp Pickett, a former Civilian Conservation Corps facility near Blackstone, Virginia, with a core group of Regular Army troops drawn from the 4th Division, which had served alongside the 79th at the Battle of Montfaucon. Taking command of the division was Major General Ira T. Wyche of Okracoke Island, North Carolina, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point (Class of 1911) and a career army officer. Wyche, the son of a Methodist pastor, had served on the Texas border and then gone to France as a member of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, seeing action with the 60th Field Artillery. After the war Wyche had primarily been employed as an artillery commander and instructor before graduating from the U.S. Army and General Staff College and being promoted to major general in March 1942. Wyche, whose secondary concentrations were supply and transportation, was determined not to make the same mistake that the AEF had: throwing the 79th Division into action at Montfaucon in 1918 without proper training or unit cohesion. After the newly constituted division was activated at Camp Pickett, Wyche saw to it that his men were drilled in field operations at the Tennessee Maneuver Area, desert warfare at Camp Laguna in Arizona, and winter combat at Camp Phillips in Kansas. The training lasted for 22 months.

The first members of the 79th Division to go overseas were part of a military police platoon sent to Africa following the American landings in Tunisia during Operation Torch. The MPs were assigned to escort German prisoners from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps back to stateside prison camps. One future member of the 79th Division, Private Roy Morris of Nashville, Tennessee, got a firsthand look at some of the German POWs while he was in basic training at Fort Hood, Texas, in late 1943. Morris had been drafted earlier that year while living in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, with his wife and infant daughter. At Fort Hood, Morris and his fellow GIs watched the tall, blond, suntanned Afrika Korps prisoners doing strenuous calisthenics all day in the Texas sun. “We’re supposed to fight those guys?” they wondered aloud. Of course, it was not the Afrika Korps that the 79th Division would encounter after landing on the beaches of Normandy eight days after D-Day, but the equally battle-hardened members of the Wehrmacht, the German regular army. Either task would be daunting.

As Allied planners worked through late 1943 and early 1944 on Operation Overlord, the plan to invade and liberate Nazi-held France, elements of the 79th Division from Camp Myles Standish near Staunton, Massachusetts, sailed for Great Britain aboard RMS Queen Mary, the requisitioned luxury liner turned troopship, in late March and early April 1944. The division landed separately at Glasgow, Scotland, and Liverpool, England. Billeted near Cheshire, England, the division underwent rigorous training in amphibious landing and assaulting fortified positions, both of which would soon be required in Normandy, on France’s extreme western coast.

As D-Day approached, the 79th Division moved from northern to southern England, concentrating in the area around Tiverton in Devonshire. There, Wyche and his key officers took advantage of their comprehensive experience in training, logistics, and supply to prepare the division—as much as possible—for the landings. Assisting Wyche were Brigadier Generals Frank U. Greer, George D. Wahl, and John S. Winn Jr.; Colonel Kramer Thomas, Wyche’s chief of staff; and Lieutenant Colonels Adolph C. Dohrmann, John A. Gloriod, Charles F. O’Riordan, Harry L. Sievers, and Herbert Sponholz. There was a lot to do and not much time to do it.

Shortly after D-Day, June 6, the 79th Division moved to embarkation ports at Plymouth, Falmouth, and Southampton. Wyche released a memorandum to be read aloud to every member of the division:

This division is now headed for the battlefield. After two years of training, I consider the division adequately trained for battle and feel perfectly confident it will accomplish its missions with distinction. In order to add to your effectiveness, I desire each of you to get yourself in a state of hatred against the Hun so that you will approach the battlefield mad as hell. Your state of mind should be that of the hunter who is bent on exterminating vermin and predators. There is one resolution that I want each of you to make and that is, to so conduct yourself in the first fight that the Boche and all our Allies will be impressed with the veteran performance of the 79th Division. May each of you have good crossing. I shall be on the beach to welcome you.

Officially, the 79th Division was one of four divisions in the American VII Corps commanded by Major General J. Lawton Collins. The advance party of the division landed at Utah Beach six days after D-Day, with the main body landing two days later. As Private Morris remembered, the beach was still “hot,” with German holdouts still shelling and bombing the Americans as they landed. During one of the bombings, Technician Harry Ribiski of Morris’s own 315th Infantry Regiment was wounded by a stray piece of shrapnel while he was still aboard a landing craft, making him the division’s first casualty in World War II. True to his word, Wyche was on hand to meet his men on Utah Beach, an unexceptional nine-mile stretch of sand dunes and sea oats centered on the Nazi strongpoint at Les-Dunes-de-Varreville. This landing point was at the far western end of the Allied line extending southwest from Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

Despite heavy casualties, the Allied landings on D-Day were successful, in large part because they were made where the Germans least expected them. The beaches at Normandy were a good deal farther from England than the traditional trans-Channel crossing between Dover and Calais. Nevertheless, the landings might have been repelled had Hitler listened to Rommel, his commander at Normandy. A tank commander by profession, Rommel had wanted to station his elite panzer tank divisions in Normandy, but Hitler overruled him. The weather, too, played a large part in the D-Day successes, since a terrible storm the night before had lulled German commanders, including Rommel, into a false sense of security. Allied weather forecasters had correctly predicted a break in the storm at dawn on June 6.

Once the 79th Division had made landfall at Utah Beach, it linked up with the other three infantry divisions in VII Corps: the 4th, 9th, and 90th. VII Corps was given the crucial assignment of seizing the Cherbourg Peninsula (also called the Cotentin Peninsula) and the deepwater port city of Cherbourg. It was absolutely vital that the Allies control the port, which would be the chief resupply and reinforcement point for Allied ships crossing the Atlantic from the United States. Wyche, at the head of the 79th, linked up with the deputy divisional commander of the 4th Division, a man with a famous name and face: Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. Like his legendary father, the younger Roosevelt was a hard-charging soldier. At 56, he would be the oldest Allied soldier to land on D-Day, splashing ashore at Utah Beach and personally repositioning troops that had been dropped off mistakenly 2,000 yards south of the planned landing zone. It was a vital battlefield decision, memorialized by Roosevelt’s terse directive: “We’ll start the war here.” He would later be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Utah Beach on June 6.

The 79th was initially held in reserve while the 4th, 9th, and 90th divisions drove west from the beach onto the peninsula proper. The 101st Airborne Division’s seizure of the crossroads village of Carentan on June 9 allowed the Allies to form a continuous front from west to east and freed VII Corps to move onto the peninsula without fear of a German counterattack in its rear. The 4th Division, operationally led by Roosevelt, moved up the beach road from Quineville toward Montebourg. The 90th Division took the 4th’s left and the 9th Division moved toward Barneville on the western shore of the peninsula. On June 18, the 9th Division captured Barneville. The American forces had essentially drawn a line across the peninsula, isolating Cherbourg from reinforcements. Hitler, bumbling as usual when he played general, overruled Rommel’s recommendation that the German forces be allowed to withdraw into the walled fortifications of Cherbourg. Instead, Hitler ordered the defenders to form a new line south of the city. Rommel, disgusted by Hitler’s interference and looking perhaps for a scapegoat, sacked General Wilhelm Fahrmbacher, the new commander of the LXXXIV Corps, for moving too slowly into the new defenses. Fahrmbacher had held his command for only three days.

That same day, the 79th Division received orders to relieve the 90th Division in the center of the American line and spearhead a three-pronged assault on Cherbourg. It was the division’s first combat assignment—and a tough one at that. The terrain facing them was uniquely difficult: north of the Valognes–Barneville line the ground was primarily hilly, but south of the line it was flat and marshy, crisscrossed by small streams and divided into countless farm fields and orchards by centuries-old mounds of earth, stone, and underbrush that Morris remembered simply as “those damn hedgerows.” The Germans, long skilled in the art of defense, had reinforced the natural earthworks with scores of concrete pillboxes and well-placed antitank guns. They had also flooded the flatlands, forcing the attackers to splash through knee-deep water and mud on their approach.

Each hedgerow represented an individual miniature battle that the division’s official historian later likened to “a game of checkers—one square at a time.” As thoroughly as Wyche had trained his men, he had not prepared them to surmount such obstacles, and new tactics of enfilading fire and over-the-head shooting plus an improvised weapon called the tankdozer—a Sherman M4A1 medium tank modified with a flat, shovel-like bulldozer attachment to plow through the hedgerows—had to be adopted on the spot. Thrashing through French hedgerows to dislodge German defenders crouched in them like so many rodents was “decidedly un-American,” one GI complained.

The 79th Division’s initial objective was the high ground west and northwest of the village of Valognes, which commanded the Valognes–Cherbourg highway and blocked access from the feeder roads on that side of Valognes. Zero hour was set for 5 a.m. on June 19. The 313th and 315th Regiments would go over to the attack, with the 314th Regiment held in reserve. The 313th jumped off first, accompanied by tank and chemical companies and supported by the 310th and 311th Field Artillery battalions. “It’s just like Tennessee maneuvers—only with live ammo,” one GI joked. No one laughed. Enemy resistance, sporadic at first, soon swelled into fierce, concentrated fire, but by 2 p.m. the 1st Battalion had reached its objective a few miles northwest of Valognes in the heavily forested Bois de la Brique.

The going was tougher for the 315th Regiment. It made first contact with the enemy near Flottenanville. A German counterattack at 3 p.m. held up the advance for four hours before it was repelled with heavy losses. Farther to the right, at Lieusaint, enemy snipers also slowed the advance, and all three of the regiment’s battalions were brought into action to clear the area. By nightfall, all the units had reached their first-day objectives, most of them ahead of schedule. Meanwhile, Wyche rethought his decision to hold the 314th Regiment in reserve and ordered it to assemble as well. The regiment’s 2nd Battalion was motorized and sent racing toward the flyspeck village of Croix Jacob, two miles north of Negreville, which it reached at 4:15 the next morning.

At 6 o’clock the same morning the 313th Regiment left the Bois de la Brique, where it had bivouacked for the night, and began advancing in echelon north along the Valognes–Cherbourg highway. The regiment’s progress was so rapid that it overran German positions at Hau de Long and captured four tanks and an 88mm gun before the retreating enemy forces could demolish them. The regiment continued to advance until heavy artillery fire halted it at Delasse.

The 314th Regiment began advancing at the same time, moving parallel to the main highway and capturing an additional eight German tanks. By 6 p.m. the lead forces had made it all the way to Tollevast, where they ran into a string of enemy pillboxes and stopped for the night. Meanwhile, the 315th Regiment spent the day mopping up the area west of Valognes that the lead regiments had bypassed, overrunning two German strongpoints and seizing several prisoners and a number of 4-inch guns. The regiment made camp for the night at an assembly area near Hau de Long.

In two days all three American divisions were within striking distance of Cherbourg. Lieutenant General Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, the German garrison’s new commander, had 21,000 troops on hand, but many of them were sailors hastily drafted from docked vessels or grudging conscriptees from labor units. The defenders were running out of food, fuel, and ammunition, and what few supplies the Luftwaffe was able to drop into the city were mostly useless items such as Iron Crosses intended to boost the garrison’s morale. Schlieben rejected calls to surrender and began carrying out demolitions inside the city.

By that point in the war, Schlieben had a nearly unbroken record of failures on his command résumé, having lost entire tank divisions on the Eastern Front at Stalingrad and Kursk. He had been sent to western France and given charge of the 709th Static Infantry Division, a poor-quality unit made up of previously wounded soldiers, older men with existing medical conditions, conscripted laborers, and Russian POWs who had agreed to fight for the Germans to escape the horrific conditions in eastern prison camps. The division had initially confronted American troops landing at Utah Beach and airborne forces farther west on the peninsula before withdrawing into Cherbourg. The defenders did have the advantage—and at first it was a large one—of having spent the last four months strengthening defenses around the port city.

On the night of June 20–21, Wyche ordered scouts from the 79th to make a thorough reconnaissance of the outer defenses at Cherbourg. Lee McCardell, a war correspondent for the Baltimore Sun, accompanied the troops and described what they discovered:

So-called pillboxes in the first line of German defenses which the 79th Division assaulted in the attack on Cherbourg were actually inland forts with steel and reinforced concrete walls four or five feet thick. Built into the hills of Normandy so their parapets were level with surrounding ground, the forts were heavily armed with mortars, machine guns, and 88mm rifles—this last, the Germans’ most formidable piece of artillery.

Around the forts lay a pattern of smaller defenses, pillboxes, redoubts, rifle pits, sunken well-like mortar emplacements permitting 360-degree traverse, observation posts and other works enabling the defenders to deliver deadly crossfire from all directions.

Approaches were further protected by minefields, barbed wire and antitank ditches at least 20 feet wide at the top and 20 feet deep. Each strongpoint was connected to the other and all were linked to the mother fort by a system of deep, camouflaged trenches and underground tunnels. The forts and pillboxes were fitted with periscopes. Telephones tied in all defenses.

Entrance to these forts was from the rear, below ground level, through double doors of steel armorplate which defending garrisons clamped shut behind them. The forts were electrically lighted and automatically ventilated.

The Germans responded to the scouts’ probes with heavy small-arms and artillery fire, shelling the assembly area of the 314th Regiment and causing some casualties. The 315th moved up through the night to the outskirts of St. Martin le Guard, with a covering force moving into place north of Le Bourg. Plans were formalized for the next day’s attack, and the troops were issued extra demolition equipment they would need when striking Cherbourg’s outer defenses. Repeated radio broadcasts were beamed into the city, urging the Germans to surrender and setting an ultimatum of noon on June 22. Schlieben again ignored all offers, and 40 minutes after the ultimatum expired the U.S. Army Air Forces began a tremendous 80-minute aerial bombardment of the enemy positions at Cherbourg. The men of the 79th had pulled back 1,000 yards or so to keep clear of the American bombing and machine-gun fire from strafing planes, but inevitably they took some friendly fire. As soon as the aerial bombardment ended at 2 p.m., the 304th Engineer Battalion went to work under fire, blasting entrances through hedgerows and building new roads alongside existing routes.

Meanwhile, the 313th Regiment jumped off on the division’s right, but it quickly ran into active enemy pillboxes. One battalion circled the enemy position and attacked it from the rear. A second battalion, spearheaded by a heavy machine gun platoon, advanced toward the primary objective, Crossroads 177, arriving at 2:05 a.m. On the left, the 314th Regiment advanced to the fortified village of Tollevast, while the 315th operated on the far left flank, maintaining contact with the 9th Infantry Division and eliminating enemy strongpoints as it went.

For the next two days the 79th proceeded toward Cherbourg, an exhausting stop-and-start advance that necessarily slowed each time the various regiments encountered German resistance. Even in late June the nights were cold, and the men dropped into foxholes and slept when they could, which was not often since enemy artillery incessantly split the night. Correspondent McCardell painted a vivid picture of the men:

The Joes looked like they could stand a Saturday night bath anywhere—not necessarily Cherbourg. Those with beards looked like burlesque tramps. All were beginning to tire a little. Many a Joe hadn’t had his shoes off for a week. His feet were killing him. He would have given ten bucks for a clean pair of 10-cent socks. Aside from canned rations and hand grenades which filled all the pockets of his grimy, mud-stained fatigues, he carried only what he wore plus his canteen, a shovel, an ammunition belt, an extra bandolier, a knife, bayonet and his rifle.

The last key to the German defense before Cherbourg was Fort du Roule, situated on a ridge running northwest to southeast in front of the city. The fort dated back to the late 18th century and had been greatly expanded by French emperor Napoleon III from 1853 to 1857. The French had strengthened the fortification before the Germans occupied it, and the Germans’ own crack Todt engineering organization had modernized it. Organisation Todt was a quasi-civilian operation led by Albert Speer, the Nazi minister of armaments and munitions. It was notorious for using forced labor, and along with constructing much of Germany’s autobahn system of highways, it also undertook construction of all concentration camps during the war.

On the morning of June 25, Allied planes dive-bombed the fort before the men of the 79th Division launched their attack. The 313th Regiment led the way to the outskirts of the city, while the 314th stormed the fort itself. Companies E and F of the 2nd Battalion attacked the eastern face of the stronghold before being pinned down by heavy machine-gun fire from the slope beneath the peak. Corporal John D. Kelly of Company E volunteered to blow the strongpoint with 15 pounds of TNT attached to a 10-foot pole charge. Advancing up the slope, Kelly placed the first charge, which was ineffective. He returned with a second charge, which blew off the ends of the enemy machine guns, and then climbed the slope a third time to place a charge against the rear entrance. He then tossed hand grenades into the ruins, forcing the survivors to surrender. For his gallantry, Kelly was awarded the division’s first World War II Medal of Honor—sadly posthumously, as he was fatally wounded in France that November.

A second member of the 314th, First Lieutenant Carlos C. Ogden of Company K, 3rd Battalion, performed feats at Fort du Roule for which he also received a Medal of Honor. When the company was pinned down by an 88mm gun emplacement and its company commander wounded, Ogden attached a grenade launcher to his rifle and started up the slope toward the stronghold. “We were tied down and were going to get killed,” Ogden would later recall, “and I thought I might as well get killed going forward as back.” Two bullets went through his helmet, grazing his head and knocking him down. He was holding a grenade with the pin pulled, and despite suffering a broken wrist in the fall, he managed to hold the grenade handle in place. He knocked out the 88 with a rifle grenade and silenced two machine guns with hand grenades. Despite being wounded in the leg as well as the head and suffering a concussion and damaged eardrums from the explosions, Ogden refused medical treatment, rallied the company, and led it forward.

Fort du Roule’s defenders surrendered at 9:48 that night. Schlieben; his second in command, Rear Admiral Walter Hennecke; and 800 other officers and enlisted men put up their hands, although the German general refused to issue a blanket cease-fire order. His stubbornness resulted in another day of unnecessary street fighting inside Cherbourg before the 313th and 315th Regiments, with minor last-minute assistance from the British No. 30 Commando unit in the eastern suburbs, secured the city on June 26, capturing a total of 6,000 German soldiers, along with a large amount of matériel. A British post-surrender intelligence report gave a less than flattering image of Schlieben: “With his pink complexion, round boyish face, huge bulk and lumbering gait he gives the appearance of an overgrown, mentally under-developed school-boy type who will bully his inferiors and toady to his superiors.…Has more bluff than guts.” The British were particularly insulted that Schlieben didn’t know whether Scotland was hilly or flat. A final humiliation for the general came when a truck loaded with his personal trunks and belongings collided with another truck, and gleeful GIs helped themselves to his gold braid and decorated dress uniforms strewn along the side of the road.

“We took that rock pile step by step,” one GI said of Fort du Roule, “and every step was a grunt.” Colonel Bernard B. McMahon, the 315th’s multilingual commanding officer, took to a mobile public-address system to urge the remaining Germans to surrender. Scores did, but others, concealed in secondary underground bunkers beneath the forts, were inadvertently blown up by American engineers demolishing the structures. Meanwhile, Cherbourg’s citizens thronged the litter-strewn streets to kiss and embrace les liberateurs. Cherbourg was the first French city of any size liberated by the Allies in the war, and the overwhelming greeting extended to the men with the Cross of Lorraine shoulder patch on their campaign jackets would be repeated often as they made their way across France. But in Cherbourg the celebration was short lived. On June 27, the 4th Division moved into Cherbourg to garrison the city, and the 79th headed south. General Ted Roosevelt would become temporary military governor of the city before rejoining his division on its drive across Normandy. Roosevelt would die in his sleep of a heart attack on July 11. Two months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented the general’s widow with a posthumous Medal of Honor in recognition of his service at Utah Beach.

Navy Seabees and salvage teams immediately went to work clearing and rebuilding Cherbourg’s damaged harbor. On July 16, the first new shipment of supplies—some 17,000 tons of rations and equipment—was offloaded. By the end of the war, nearly three million tons of cargo had entered via Cherbourg, along with 130,210 fresh combat troops.

In its first battle, the 79th Division had performed superbly. Against numerically superior (if sometimes qualitatively inferior) enemy forces holding an intensely fortified city situated on commanding heights, the division had smashed through to victory, after fighting its way across the flooded countryside. It was, Wyche said, “a brilliant beginning,” but he, better than anyone, knew that it was only the beginning. Ahead lay 240 more days of combat and thousands more casualties. For the 79th, in the words of the traditional hymn, there were still literally “many rivers to cross.”

The 79th Division had taken Cherbourg, but the Germans still had forces spread across the Carentin Peninsula, from Denneville on the extreme western flank east through St. Lô to Carentan. To link up with other advancing Allied troops—and to avoid being trapped in a bottleneck on the peninsula itself—Wyche set the division in motion on July 3. Plans called for the 314th Regiment to cross a tributary of the Douve River and capture an enemy strongpoint designated Hill 121. At the same time, the 315th would attack farther west in the direction of Hill 84 near Montgardon. The 313th was held in reserve.

Once again the GIs in the division faced a tenacious, desperate enemy holding the hedgerows and contesting all the roads leading south. Ubiquitous 88mm artillery pieces were augmented by dug-in panzers and deadly snipers. At zero hour, 5:30 a.m. on July 3, the regiments set out in a cold drizzle toward their objectives. Both regiments took their initial targets by midafternoon, supported by artillery and tanks, though resistance was heavy. Hitler himself had ordered the Germans in the hedgerows, many of whom had been bypassed on the lightning drive toward Cherbourg, to fight to the last man. Not all did so, but these “suicide units” grimly contested the Americans’ progress. By day’s end, both regiments were halfway toward their ultimate objectives. The advance was halted for a day to allow General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe, and his second in command, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, to visit the division command post at Les Fosse while American artillery “serenaded” the enemy in a gala Fourth of July commemoration.

The next morning the two lead regiments moved forward again, with the 313th joining in. Increasingly, the attack focused on the enemy stronghold at La Haye-du-Puits. The Germans fought bitterly for every inch, but Lieutenant Colonel James B. “Kannonball” Kraft’s 312th Forward Artillery Battalion unleashed what one observer called “the prettiest damned precision artillery in this man’s war,” paving the way for Lieutenant Colonel Olin E. “Tiger” Teague’s 314th Battalion to advance to the very rim of the city. Enemy observers in the bell tower of the village cathedral observed for a bit too long, and Kraft’s gunners sent a burst directly through the steeple. When GIs entered the square afterward, they found the bodies of the bell tower watch sprawled across the cobblestones below.

After taking Hill 84 (and encountering for the first time the vaunted troops of the 2nd Schutzstaffel [SS] Division), the men of the 315th were joined by the 313th, which helped beat back an intense counterattack on the promontory the Germans were calling “Bloody Hill.” Meanwhile, the 28th Infantry Regiment from the 8th Division reinforced the 314th Regiment, along with two tank battalions, for a final push into La Haye-du-Puits. For nearly six hours the Americans fought house to house with the German defenders, who eventually fell back to the town’s railroad station for a last stand. GIs said the paint was still wet on numerous German-language “Off Limits” signs at the station. Finally, Teague reported that the city belonged to the 79th. Tennessee-born Lieutenant Arch B. Hoge Jr. raised a small Confederate flag in the city—the same flag his uncle had raised over a French village in World War I and his grandfather had raised during the Civil War. The 1st Battalion of the 314th was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for its part in the fighting.

Mopping up enemy diehards on Hill 84, the men of the 315th got a firsthand view of their division commander in action. On one of his daily visits to the front, Wyche found a platoon pinned down on the slope of the hill. Repeatedly exposing himself to enemy fire, Wyche helped regroup the men and led them through two hedgerows to knock out the German position on the crest. Wyche even managed to help evacuate a wounded infantry scout from the field.

Small, wiry, and intense, Wyche was popular with the men, who called him “Papa Wyche” for his daily inspections and his obvious attention to their well-being. His headquarters flag, two gold stars on a red background, was usually at or near the front. An accomplished horseman who had begun his career with the mounted service, Wyche now rode into combat in a jeep, his handsome, deeply lined face familiar to all the GIs under his command. They appreciated his willingness to lead from the front, and he repaid their affection by focusing on every detail of his command. This included establishing a special pool of experienced officers, noncoms, and veteran frontline troops to train replacements before they went into action. Other divisions soon adopted Wyche’s innovative training system.

Highways south and east of La Haye-du-Puits were still infested with German defenders and heavily mined. It would take the 79th 11 days to clear the peninsula. In doing so, the division suffered 2,930 casualties. The Germans withdrew to the south bank of the Ay River, while inclement weather grounded Allied planes and allowed the enemy to reinforce positions with 88mm artillery pieces and mortars and blow strategic bridges across the river. At one dynamited bridge, Private Frederick F. Richardson of Company F, 315th Regiment, personally beat back two German counterattacks over two days and nights. Setting up his Browning in a window of a stone house 300 yards from the bridge, Richardson blasted away, killing or wounding 40 attackers. Finally, after allowing the enemy a three-hour ceasefire to remove the wounded from his field of fire, Richardson was amazed to see a German lieutenant approach with 19 men, waving a white flag of surrender. He remained at his post, where a mortar round subsequently blew off one of his legs. Richardson’s only complaint to the medics carrying him to the rear in a stretcher was that he could not “go back and kill more Germans.” He would be awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for his actions on the Ay.

The Germans abandoned their line south of the Ay River and fell back toward the stronghold of Lessay. The 79th Division joined the massive Allied effort known as Operation Cobra, which was designed to break out of the Normandy beachheads and cut off the German forces before they could withdraw to defensive lines farther north and east of the coastal regions. The operation was under the direction of Bradley, with Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery leading the British and Canadian efforts to capture Caen and pin down the Germans there.

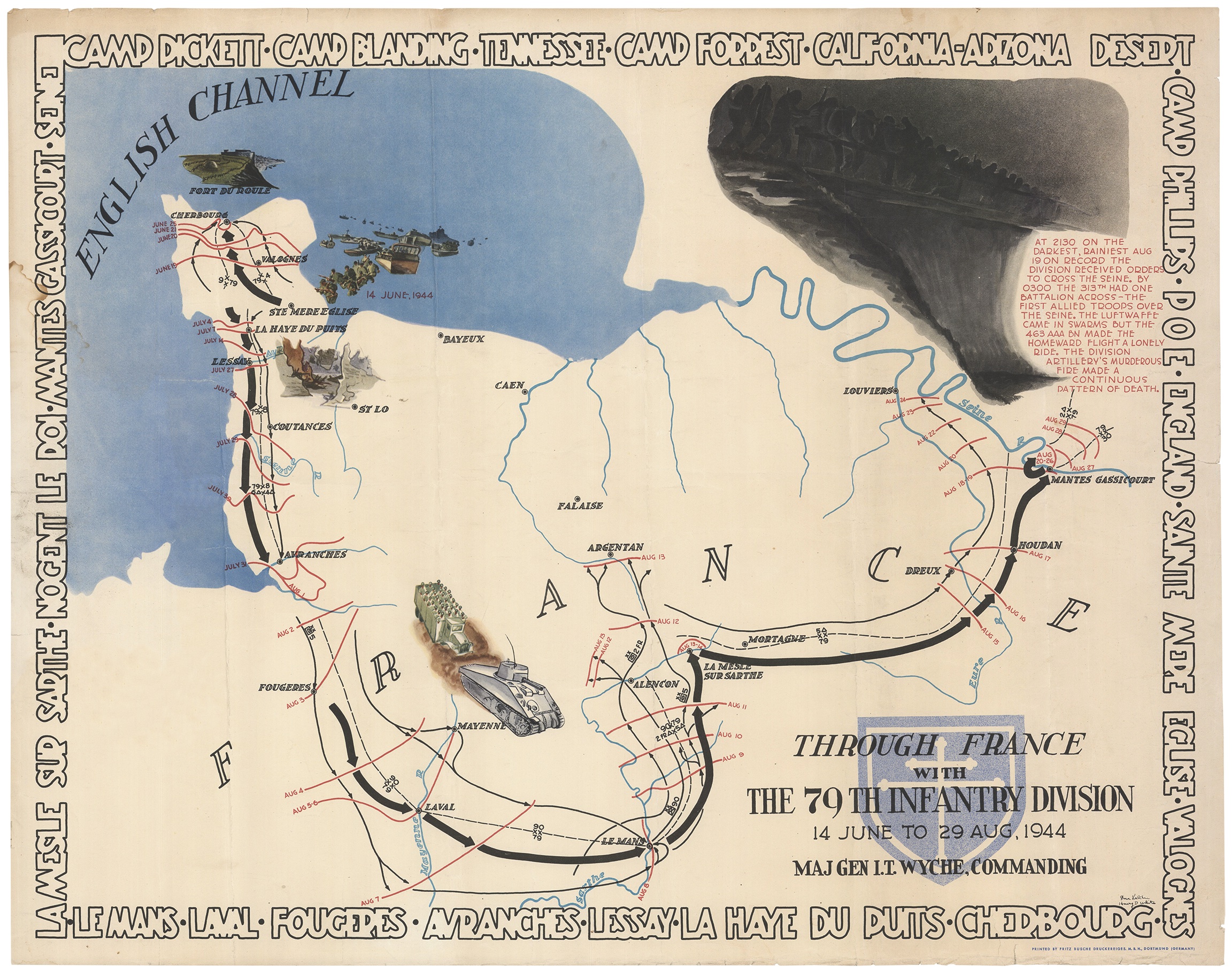

As part of the newly constituted VIII Corps, the 79th Division crossed the Ay River on July 26 and captured Lessay. American armored divisions spearheaded the advance. VIII Corps was attached to Lieutenant General George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army and given the task of protecting its left flank. Transferred to XV Corps and now motorized, the division headed first to the city of Fougères and then drove on to Laval, with elements of the 313th and 314th Regiments crossing the Mayenne River by boat and helping throw up a floating Bailey bridge. The 315th followed, and the division entered Laval on the afternoon of August 6. From Laval the division advanced to the important industrial city of Le Mans. The 315th was motorized and ordered to assist in the capture of Le Mans. The city fell on August 8.

The war had entered a period of lightning advances, with the 79th and other infantry divisions following the American armored divisions as they swung northeast in an attempt to encircle the German Seventh Army near Mortain. The 79th advanced in its now-familiar three-pronged formation, converging on the village of Nogent-le-Roi on August 15. Enemy resistance was slight, with the exception of three Luftwaffe planes that attempted to dive-bomb the assembly area and were quickly shot down by the 463rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion. Reunited, the division moved onto the ridges overlooking Mantes-Gassicourt, where the Seine looped lazily west-northwest. With the 315th left in reserve, the 313th and 314th Regiments moved quickly north to help trap the enemy in the inland peninsula formed by the looping river.

For five days the desperate Germans counterattacked the two regiments in the vicinity of Dennemont. Lee McCardell of the Baltimore Sun described the American position as “a stubby finger, sticking into enemy territory…a sort of a Bunker Hill proposition.” McCardell said the men had placed machine-guns behind a wall in which they had made embrasures. There the veterans sat, “calmly smoking as they watched the desperate Germans advance,” he wrote. “They held their fire until they could almost see the whites of their eyes.” The 313th and 314th had advanced so quickly that the German press misidentified their advance as an airborne landing. At one place, Colonel Sterling A. Wood, the commanding officer of the 313th, counted 39 enemy dead in a 50-square-yard area. “I’ve never seen anything like it in any other engagement in this war,” he said, “and we’ve had some pretty stiff ones.”

General Bradley pressed the men forward, declaring: “This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once a century. We’re about to destroy an entire hostile army and go all the way from here to the German border.” His ever-aggressive Third Army commander, Patton, who personally visited the 79th’s bridgehead on August 19, was inspired to write a poem about the apparent inevitable tide of the battle: “So let us do real fighting, boring in and gouging, biting. / Let’s take a chance now that we have the ball. / Let’s forget those fine firm bases in the dreary shell raked spaces, / Let’s shoot the works and win! Yes, win it all!”

As it turned out, the generals were overly optimistic. The disciplined German army, despite suffering enormous losses from D-Day onward, managed to hold open the soon-to-be-infamous Falaise Gap, a break in the Allied lines, long enough for 50,000 soldiers to escape the jaws of defeat, death, or capture. Pushing past the valiant but outgunned 1st Polish Artillery Division at Hill 262 near Chambois, the German survivors managed to cross the Seine ahead of their pursuers. Montgomery and his surrogates complained that Patton had not swiftly blocked the German retreat—surely the only time in his career, civilian or military, that Patton had been accused of being too slow or not aggressive enough. In fact, Bradley had held him back: “Although Patton might have spun a line across the narrow neck, I doubted his ability to hold it,” Bradley later wrote. “Nineteen German divisions were now stampeding to escape the trap. Meanwhile, with four divisions George was already blocking three principal escape routes through Alencon, Sees, and Argentan. Had he stretched that line to include Falaise, he would have extended his roadblock a distance of 40 miles. The enemy could not only have broken through, but he might have trapped Patton’s position in the onrush. I much preferred a solid shoulder at Argentan to the possibility of a broken neck at Falaise.”

Historians have long debated whether Bradley, in deciding to leave Falaise Gap open, unwittingly prolonged the war by allowing thousands of battle-tested German soldiers to live to fight another day. In any event, between D-Day and the time the Allied forces closed Falaise Gap on August 22, the Germans lost a staggering 240,000 men. In its portion of fighting around the Seine loop, the 79th alone had inflicted more than 25,000 casualties, taken 12,000 prisoners, and seized or destroyed 200 German tanks, 235 artillery pieces, and 675 armored vehicles. The division’s antiaircraft units had shot down an additional 50 Luftwaffe planes. Three days later, on August 25, Paris was liberated.

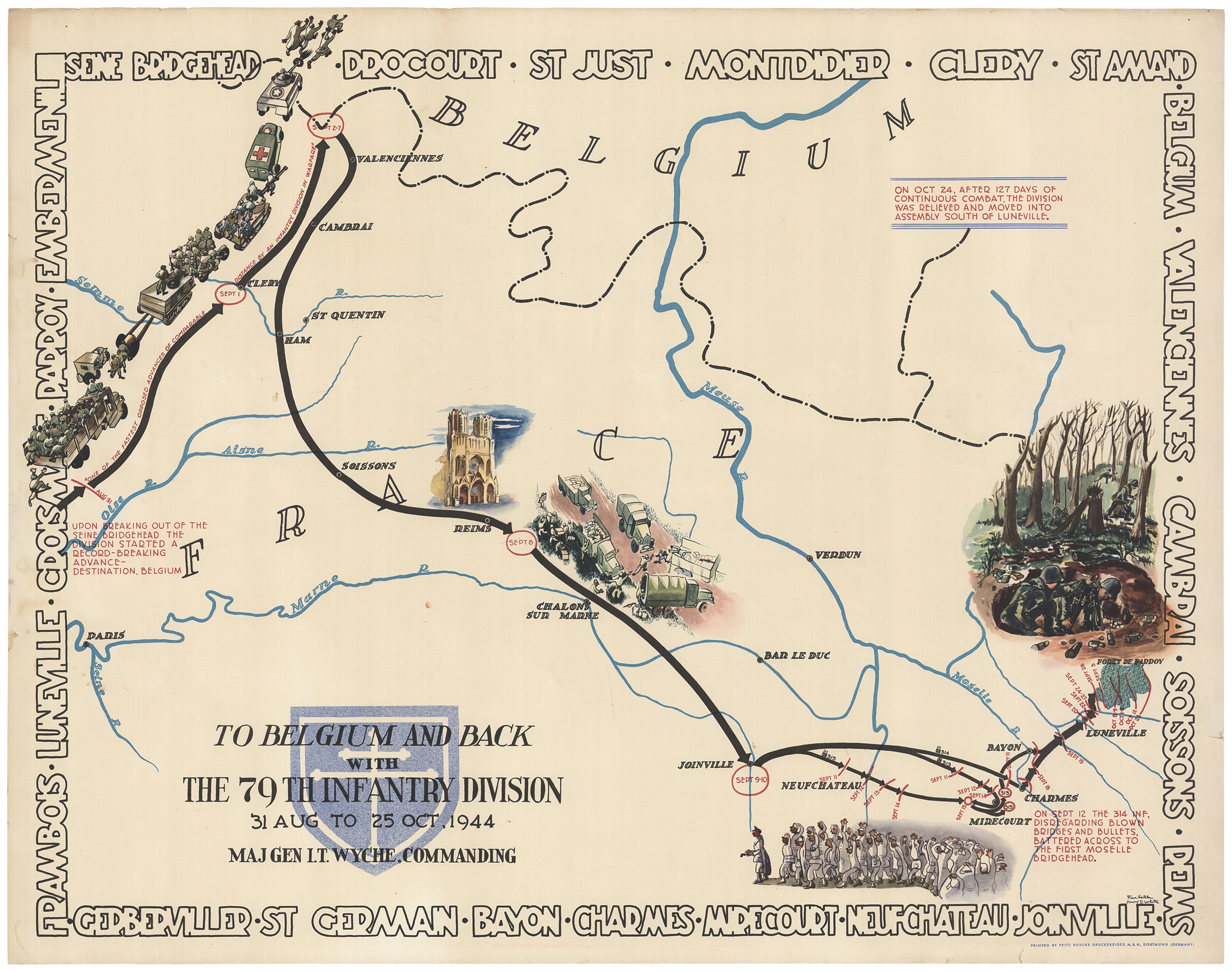

On August 28 the 79th was transferred to XIX Corps. It would bypass Paris altogether—much to the disappointment of the men—and head northeast into Belgium. In just 72 hours the division covered 180 miles, passing over legendary World War I battlegrounds at the Somme and becoming one of the first American divisions to cross into Belgium in World War II. Major General Charles H. Corlett, the commanding officer of XIX Corps, told Wyche it was “believed to be one of the fastest opposed advances of comparable distance by an infantry division in warfare.” Behind the praise lay acknowledgment of the division’s superb performance, particularly in taking and rebridging various rivers and streams the Germans had destroyed as they retreated. Much of the credit went to the men of the 304th Engineer Battalion, who threw up three new bridges over the Somme alone with whatever materials they found at hand—often while under fire from enemy planes.

On September 5 the division turned south toward Reims and a reunion with Patton’s Third Army. Meanwhile, the German Nineteenth Army was in full retreat toward the wooded hills overlooking the Moselle River. Once again the division’s three regiments advanced separately, with the 313th aiming at Poussay and Ambacourt and the 314th heading for Charmes. The 315th’s objective was Neufchâteau. Although they didn’t realize it at the time, the hard-marching men in the 79th had traversed the entire front of the German 16th Infantry Division—an almost unheard-of feat against the highly trained enemy.

On September 12, in one of its fiercest attacks of the war, the 315th overran Neufchâteau. Led by Lieutenant Colonel John H. McAleer, the regimental combat team spearheaded the assault under cover of darkness at 1 a.m. The 1st Battalion moved in from the northeast, while the 2nd Battalion took up positions south of the town to block any enemy reinforcements from that direction. The regiment’s scouts received valuable assistance from an unlikely source: a 19-year-old British airman, Walter Farmer, whose Lancaster bomber had been shot down near Liège in March. He had joined the French underground while making his way to Switzerland. Farmer ran into the scouts on patrol and agreed to sneak into Neufchâteau to ascertain German strength and locations. He was almost captured by the Germans, but townsfolk managed to lift him onto the roof of a barn in the nick of time. Bitter street fighting went on all day and night, with the Germans making full use of the crumbled buildings to mount a last-ditch defense. Despite the stubborn resistance, the 315th gained control of the town by midnight.

Moving east toward Châtenois, the regiment came upon a German lieutenant carrying a flag of truce. Interrogators learned from the officer that his commander, a colonel named Wetzel, wanted to discuss terms of surrender. The German motorized regiment, headquartered nearby in a château at Bazeilles, had found itself pinned between the 315th and the 2nd French Armored Division. Wetzel was ready to surrender to the Americans, provided they would promise not to hand him and his men over to the French forces in the vicinity, whom he described as “terrorists.” A quartet of regimental officers and a sergeant met with Wetzel, a highly decorated 30-year veteran of the German army who had lost an eye on the Russian front. The official regimental history dryly noted that Wetzel “indicated that this was not one of the happiest moments of his life.” On the morning of September 14, Wetzel surrendered his entire regiment to the assistant 79th Division commander, Brigadier General Frank Greer. Included in the haul were 45 trucks, 29 personnel carriers, five motorcycles, three Red Cross trucks, two 88mm guns, a six-gun battery, and two half-tracks.

The 315th drove on to Châtenois, overcoming stiff resistance there, and then linked up with the 313th at Dombasle, where the two regiments formed a pocket to trap an additional 500 German prisoners. A wild night of fighting at Ramecourt resulted in the destruction of another enemy force. In five days the division captured a total of more than 2,200 prisoners and annihilated the famed German 16th Infantry Division.

On September 18 the division got a well-earned respite when Bing Crosby, the famous singer turned movie star, brought his USO company to the area for two shows. Crosby, singer Dinah Shore, and the rest of the cast had crossed the Atlantic aboard the Queen Mary and performed at the site of the division’s singular triumph at Cherbourg and across eastern France. The troupe planned two performances for the regiments: an afternoon show at Ambacourt and an evening show at Charmes, where a large stage was built in a field and antiaircraft guns were placed at various points to safeguard against dive-bombing Luftwaffe planes. The second show had just begun when loudspeakers blared orders for the troops to return to their units and prepare to move out immediately. Crosby gamely proceeded for 15 minutes, but as the audience continued to dwindle, he finally gave up. The division was headed out for Lunéville and Morville. The men had not even gotten to hear Crosby’s signature closer, “White Christmas.”

Four more days of fighting ensued as the division drove forward to establish a bridgehead on the Meurthe River near Fraimbois. The flat, barren terrain leading to the chest-deep river and the dense woods beyond provided the Germans with a formidable defensive position. The 3rd Battalion of the 314th Regiment would be given a Presidential Unit Citation for its performance at the Meurthe, where it suffered 31 killed and 160 wounded while capturing 46 prisoners and killing or wounding an undetermined number of enemy. “We climbed Fort du Roule, and we crossed the Meurthe River,” said 3rd Battalion commander Lieutenant Colonel Ernest R. Purvis. “If we had to do one of the two over, we’d take Fort du Roule every time. Compared with this operation, Fort du Roule was a picnic.” Division veterans began referring to the Meurthe River crossing as “Little D-Day.”

The battalion’s crossing was aided by an extraordinary act of heroism on the part of Private (later Sergeant) Claude K. Ramsdail of Company L, who volunteered to obtain firsthand intelligence about enemy troop strength and gun positions beyond the river. Armed with his M-1 rifle, Ramsdail started toward the river. Enemy machine-gunners and snipers opened fire as soon as they saw him, but somehow, Ramsdail later recalled, he “managed to walk between the bullets.” Reaching the river’s edge, he snapped off two quick shots at snipers firing from a nearby farmhouse and then began wading across the river with his rifle over his head. He took cover midstream behind a stalled enemy tank destroyer and wigwagged prearranged hand signals to a friendly tank destroyer crew about a camouflaged German tank he had spotted nearby. They took it out. Ramsdail then exchanged fire with an enemy machine-gun nest, suffering .50-caliber bullet wounds to his right leg and left shoulder. Blown off his feet, Ramsdail almost drowned before he regained his footing and dragged himself onto the riverbank. Artillery took out the machine-gunners and the battalion stormed across the river. They found three dead snipers in the nest and two more in the farmhouse, along with 43 Germans ready to surrender.

The division reassembled around Lunéville on September 22 for a difficult new assignment. A salient had opened on the southern flank of Patton’s Third Army near the Forêt de Parroy in northeastern France. The forest, a sentimental favorite of Hitler’s because he had fought there as a corporal in World War I, had been strongly fortified by the crack 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The Germans had been ordered to hold to the last man. Against this fanatical force of defenders the men of the 79th would have to fight hand to hand, tree to tree, and boulder to boulder. It would be a daunting task, considering the enemy’s advantages: The Germans had a commanding view of the terrain, they occupied existing French defenses, and they had implanted tanks and assault guns—difficult to knock out under the heavy covering of trees.

The 314th Regiment was held in reserve, while the 313th and 315th pushed ahead, first to Jolivet and Chanteheux and then to Crion and Sionviller. Poor weather shut down aerial bombardments, hampering the advance for several days. Scout patrols ran into heavy resistance almost immediately. The 312th Field Artillery Battalion and XV Corps Artillery exchanged heavy fire with German batteries. Finally, on September 28, American bombers struck the forest for an hour and a half.

Following the bombing the 313th and 315th Regiments jumped off on the morning of September 29, using the main east–west road through the forest as a boundary line. The 315th reached the edge of the woods without much opposition but later ran into heavy machine-gun and artillery fire and had to bring up tanks and tank destroyers to clear the resistance. The GIs pushed into the shadowy forest, not knowing that they would face 14 days of solid fighting—bluntly described as “hell” by division historians—before emerging from the other side. The 313th, on the right flank, crossed the Vezouze River and beat back a number of German counterattacks with the aid of several bazooka teams. The 314th went back into action at the southwestern edge of the forest and linked up with the 315th.

By October 1 the division had advanced a third of the way through the forest, on roads that had to be constructed by engineers under fire from uncomfortably close enemy gunners. An engineer sergeant recalled the action in the knee-deep mud: “One rainy, miserable day we got a call to clear a minefield. The first 100 yards of a so-called road were clear. Then we came to a knocked-out jeep and two dead medics, victims of a Regal mine. Bouncing Bettys [S-mines] were all around. We started clearing this quagmire—and somebody stepped on a Betty. There were five casualties in the space of seconds. The rest of us gave them first aid and carried them out on makeshift litters.” The next day three more engineers were similarly injured. It was impossible to get a jeep up to the front to evacuate them.

The fighting continued grimly in the medieval shadows of the forest. Heeding Hitler’s orders, the Germans threw four full divisions into the Parroy, including an old familiar opponent, the 11th Panzer Division, which the 79th had faced at Cherbourg. Each day more and more of the enemy staggered into the American lines, holding up their hands and shouting that they had had enough. Finally, on October 8, plans were set in motion for a full-scale assault the next morning to clear the forest once and for all. The 314th and 315th would attack an enemy strongpoint at a crossroads three-fourths of the way into the forest. The 313th would circle around and link up with the other two divisions there. As proof of the importance the American high command placed on the Parroy, General George C. Marshall, the chief of staff of the U.S. Army, and other ranking group and corps commanders, visited the division’s advance headquarters on the day of the attack and observed the final assault from high ground just behind the lines.

The final assault began at 6:30 a.m. and lasted until 3:30 p.m., when all advancing troops reported that they had cleared the woods and reached the eastern edge of the forest. Five more days of bloody fighting were needed to clear the high ground beyond the Parroy at Emberménil, two miles away. In all, the 79th Division suffered 2,016 casualties in the Battle of the Parroy Forest, and inflicted three times that many, while taking 1,249 prisoners. Elements of nine German divisions took part in the futile defense, including the elite 29th Panzer Regiment, last reported in action on the Russian front. Two companies from the 315th Regiment—A and F—received Presidential Unit Citations for their actions at Emberménil.

The division was relieved by the 44th Infantry Division on October 23, having spent 127 consecutive days in combat. The next 16 days were given over to rest and recuperation at Lunéville, where the men slept in beds for the first time in four months. Wyche, while praising his men, urged each man to perform better in the future “by intelligent rest and recreation and correcting all his deficiencies.” The race to the Rhine was about to begin. They would need all the rest they could get.

The division reassembled near the village of Montigny and moved on to the attack in the early morning hours of November 13. As part of XV Corps, the 79th had been given the key task of seizing the town of Sarrebourg and forcing the legendary Saverne Gap through the Vosges Mountains dividing France from Germany. The ultimate objective was the strategically vital city of Strasbourg, situated just west of the Rhine River and fought over by the French and Germans for centuries. The 314th and 315th Regiments took the lead, with the 313th in reserve. The vaunted 2nd French Armored Division, which had been the first unit to enter Paris during the liberation, stood by to rush through Saverne Gap once it was cleared.

The Vosges was a comparatively low mountain range, but one that had been strategically important since 58 bce, when Julius Caesar led the Romans to victory over the Germanic tribes. In World War I, the Vosges was the site of the only mountain fighting on the Western Front. The mountains changed hands four times in 1914 and 1915, with the Germans gaining control and throwing up lengthy defensive works in the eastern foothills between Réchicourt-le-Château and Blamont in the south and Harbouey to Baccarat in the north. The fortifications included antitank obstacles, pillboxes, fortified gun emplacements, weapons pits, and strongpoints. It was those works that the German defenders reoccupied in the fall of 1944. They considered the Vosges defenses impregnable.

In a week of heavy fighting the 79th Division drove the Germans from their supposedly impregnable positions, clearing the way for the French 2nd Armored Division to take Strasbourg on November 23. The 1st Battalion, 313th Regiment, was the only American unit to accompany the French into the city, giving the men in the division yet another distinction: They were the first Americans to catch sight of the Rhine in World War II. The retreating Germans, embarrassed by their losses, dropped pamphlets into Strasbourg warning citizens: “If General de Gaulle thinks he is now in possession of Strasbourg, he is mistaken. Even if his surprising attack for the benefit of his prestige was successful, that does not mean that there will not be a sad awakening for him very soon. Not for a moment will the German Reich consider giving up German Alsace. Always Remember: The German Army will soon be here again!” It was a boast the Germans would not back up.

The 79th, led by its Reconnaissance Troop, patrolled the Alsace region, rounding up and interrogating captured German soldiers from the 25th Volksgrenadier Division, the 62nd and 109th Infantry Battalions, and 30 members of the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) ranging in age from 14 to 16. Meanwhile, the 315th Regiment seized Schweighausen on the Moder River, a few miles west of the major enemy supply center at Haguenau, forcing a river crossing under heavy infantry, artillery, and Luftwaffe fire. The 315th continued on toward Haguenau, while the 313th attacked Bischwiller on the right. The Germans, desperate to escape, attempted to blow bridges crossing the Moder. One effort was personally thwarted by Captain William McKean of Braintree, Massachusetts, a battalion executive officer in the 313th, who dove into the river under heavy fire and cut the wire leading from dynamite charges under the bridge to a 500-pound bomb atop the structure. “I didn’t know whether handling the wire would set off the TNT,” McKean recalled. “I felt pretty good when nothing happened.” McKean later received a Silver Star for his actions that day.

On December 11, the 314th Regiment stormed into Haguenau. Four days later, the division united at Lauterbourg and Scheinbenhardt on the Lauter River, the boundary between France and Germany. Staff Sergeant Dewey J. White had the honor of being the first division member to set foot on German soil in the war. Two captured enemy documents were particularly illuminating. The first, an intelligence advisory from the 361st Volksgrenadier Division, noted that “the 79th Division is known to have fought particularly well in Normandy, and is considered to be one of the best attack divisions in the United States Army.” Wyche would quote the unnamed German’s assessment in his introduction to the unit history in Stars and Stripes in 1945. The second document was an Order of the Day from the commander of the 356th Volksgrenadier Division, urging his men “to take a close grip on your rifle and hold our old border city of Haguenau for the Fuehrer.” He was not persuasive: Only a handful of snipers resisted the 314th’s entry into the city.

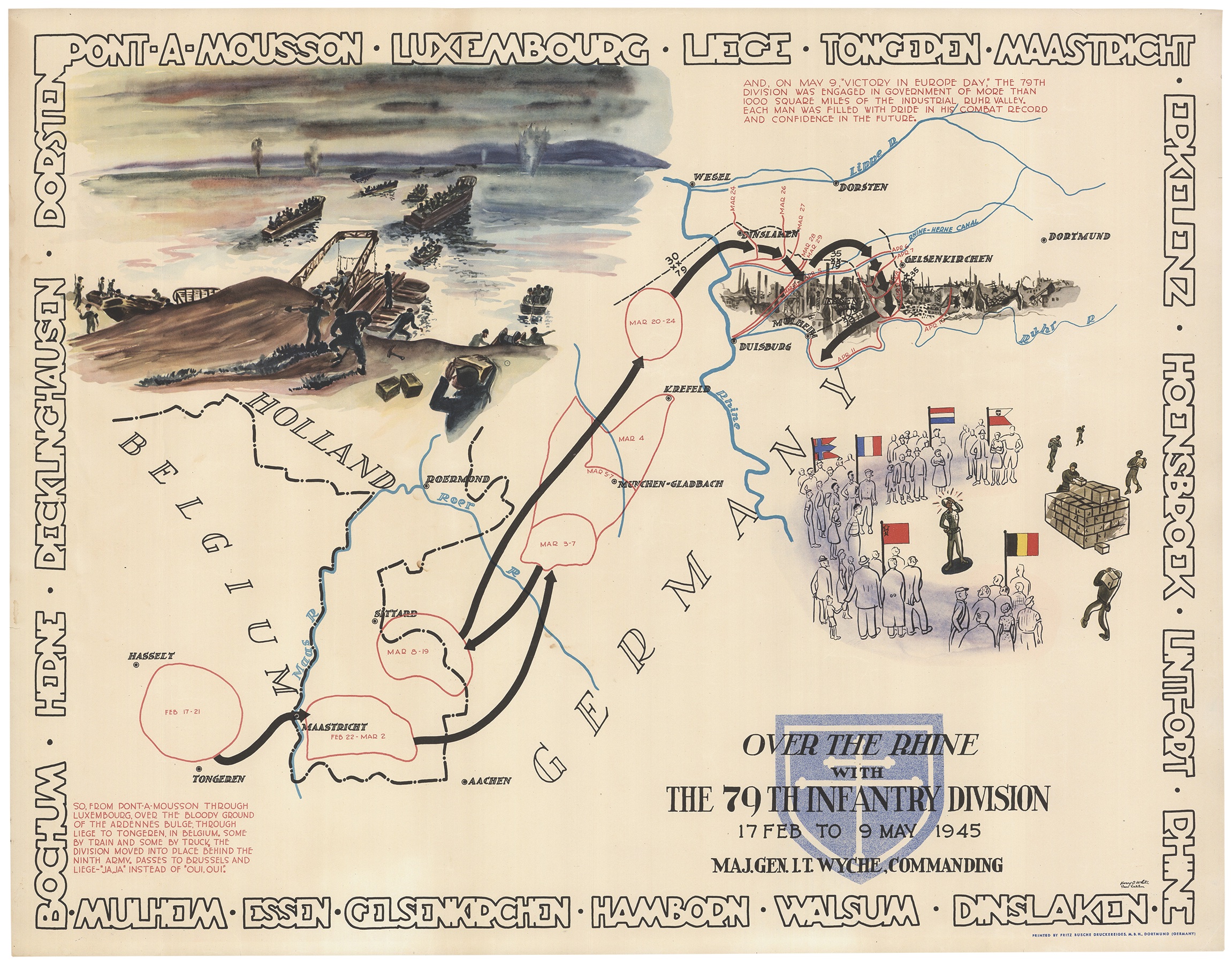

While the Germans launched their surprise offensive through the Ardennes—the soon to be famous Battle of the Bulge—the 79th probed the German defenses northeast of the captured cities of Lauterbourg and Scheibenhardt and then fell back to the Lauter River at Wissembourg, so that the Third Army could detach itself for a lightning dash north to relieve the besieged city of Bastogne. For the first time since landing on Utah Beach starting six days after D-Day, the division went on the defensive. It had captured a total of 21,311 prisoners in the interim.

For the next six weeks, while the Battle of the Bulge raged to the north and west, the 79th Division held its position, which extended roughly from Cleebourg on the left flank through Ingelheim and Aschbach to Hatten, one mile east, and then through the Haguenau Forest to the Rhine River east of Sessenheim. The new year opened with a strong attack on the 79th’s brother division, the 45th Infantry, on the left flank in the vicinity of Reipertswiller. The 79th sent four battalions to counter the threat and on January 2, 1945, withdrew, under orders, to the rebuilt Maginot Line defense, first constructed by France in the 1930s in a futile effort to deter a German attack.

Three days later the Germans attacked across the Rhine north of Gambsheim, seizing that town and occasioning a fierce counterattack by the 314th Regiment and the 3rd Algerian Division, which had been attached to the 79th for support. A second front opened north of Kilstett on January 7. The 79th found itself fighting on two fronts.

For 11 days the division fought fiercely against some of the enemy’s best remaining troops: the 21st Panzer Division, 25th Panzer Grenadier Division, and a full regiment of the 7th Parachute Division. Three battalions of the regiment, the 2nd and 3rd and the 310th Field Artillery, received Presidential Citations for holding off “fanatical” German tank and infantry attacks in the face of their own food, medical, and ammunition shortages. Lieutenant Morris W. Goodwin of Company F, 2nd Battalion, said his men refused an order to fall back, telling him, “We’ve run as far as we’re going to run.”

A backhanded compliment—the only kind the Germans generally handed out—came later from a former Wehrmacht battalion commander who had been captured after the fighting at Hatton. Major Wilhelm Kurz of the 125th Panzer Grenadiers, a veteran of 30 battles on both the Eastern and Western Fronts and a holder of his country’s highest honor, the Knight’s Cross, told his 79th Division captors: “I never thought much of Americans as soldiers until I fought them at Rittershoffen, but there we found an antagonist who defended bitterly and with more determination than we had previously seen Americans demonstrate.”

Under orders from the Seventh Army high command, the 79th Division fell back on January 20 to a new defensive line south of Haguenau on the Moder River. Its men were frustrated, feeling that they could have cleared Hatten and Rittershoffen of all remaining enemy had they been allowed to stay. Instead, for the next three weeks the division beat back repeated sorties and countersorties by more elite German troops, including the 10th SS Panzer Division. The Germans left 300 dead and another 100 captured after an aborted attempt to cross the river on pontoon boats. On February 7 the 36th and 101st Airborne Divisions relieved the 79th, after it had put in another 87 days of continuous combat. Wyche called the division’s performance “masterful.”

After extensive river-crossing training in Holland that the exhausted GIs who took part in it dubbed “the Big Sweat,” the division moved into position south of Linfort, Germany, in preparation for an all-out push across the Rhine. Underscoring the importance given to the assault, General Eisenhower himself visited 79th Division headquarters on March 24. According to a reporter from the division’s newspaper, the Lorraine Cross, the men were eager to get underway: “One doughboy in the 315th Regiment made this statement about the proposed operation: ‘Practice, move, wait. Practice something else, move the other way, then wait some more. Then repeat the process.’” Others warned that the crossing could turn into a debacle, leaving the division with “its heels in the Rhine and fighting between the devil and the drink.”

The attack across the Rhine was preceded by an intense one-hour artillery barrage, the greatest of the war, with Allied artillery firing 300,000 rounds into the German lines from 1,250 guns of all sizes. Sergeant William McBride, No. 1 gun chief for Charley Battery, 311th Field Artillery Battalion, inscribed the last round “300,000” before touching it off.

Following the barrage, it took a mere 29 minutes for 2nd Battalion, 313th Regiment, to motor across the slow-flowing Rhine and seize the village of Overbruch. The 1st Battalion was next to cross, followed by the 2nd Battalion, 315th Regiment. By nightfall all assault teams were across the fabled river. The regiment suffered fewer than 30 casualties in the crossing, most of these coming from men falling overboard in the icy water or slipping on the dike beyond. Captain John E. Potts, S-3 (operations officer) of the 315th, had to be pulled from the water when his overloaded boat shipped water and swamped. Lieutenant Colonel Earl F. Holton, the battalion’s commander, fished him out of the water, joking: “Well, I’ll be damned. What’s my S-3 doing swimming out here when we have work to do?” Clinton Conyer, a United Press correspondent who made the crossing with the division, reported that it had been carried out with “ferryboat precision.”

The division faced sporadic resistance the next several days but managed to capture a factory and take control of the autobahn beyond Dinslaken. On March 28 the division attacked abreast, seizing the Neue Emscher Canal and overrunning Hamborn. By the end of the month, the 79th had achieved its primary objective: seizing the Rhine–Herne Canal.

The division’s last combat push took place April 8–16, when the 313th and 315th Regiments led the efforts to seize control of the north bank of the Ruhr River and close the “Ruhr Pocket” that had developed between the U.S. First and Ninth Armies. The bridgehead effectively cut off more than 18 enemy divisions. One of the last of the 35,466 Germans taken prisoner by the division was industrialist Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, the owner of Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp, a key supplier of weapons and matériel to the Nazi regime and the Wehrmacht.

On April 16, 1945, the 8th Infantry Division linked up with the 3rd Battalion, 313th Regiment, between Kettwig and Steele, relieving the 79th Division and concluding its last physical contact with the enemy after 302 days of combat from Utah Beach to the Ruhr. In the course of its service, the 79th Division suffered a total of 15,203 casualties, including 2,476 killed, 10,971 wounded, 1,186 captured, and 579 missing in action. Among those reported missing was Private Roy Morris, whose wife, Margaret, received the much-dreaded Missing in Action telegram at her parents’ home in Nashville in early January 1945. Such MIA telegrams were known to precede Killed in Action telegrams.

In this case, Morris was missing because his platoon sergeant had been killed before completing a final report detailing Morris’s evacuation to the rear with frozen feet and a minor shrapnel wound to the hand. A follow-up telegram reported that Morris had been “slightly wounded in Germany on December 28.” By then, he had managed to send a letter home from a hospital in England, where

he was recuperating and helping to organize live-entertainment shows in various hospitals and camps. Morris would survive the war, return to Tennessee, and go on to a successful career in radio and television broadcasting, begun on the stages of England.

Also surviving the war was First Lieutenant Robert O. Hogan. During occupation duty with the division in Germany after the war, Hogan met a beautiful young Hungarian woman, Rozalia Maria Szarka, a stage actress who had been forced to work as a slave laborer in a German ball-bearing plant. They married and went back to Hogan’s hometown, Oklahoma City, and then, in a few years, to

Indianapolis, where Hogan became the assistant secretary treasurer of the International Typographical Union.

Morris and Hogan were two of the lucky ones, and they never forgot it. Nor did they forget their service with the 79th (Cross of Lorraine) Division, which had fought its way across Europe all the way from the beaches of Normandy to the Bavarian foothills beyond the Ruhr. My father kept his divisional shoulder patch displayed in his foldout wallet for the rest of his life. He didn’t talk much about the war, although when as a boy I asked him whether he had ever been in any big battles, he replied: “Son, when some German SOB is standing behind a tree shooting at you, it’s a big battle.” Only a true combat veteran would have put it that way. As that unnamed German intelligence officer had observed, the 79th was indeed “one of the best attack divisions in the United States Army.” MHQ

Roy Morris Jr., a regular contributor to MHQ, is the author of nine books, including, most recently, Gertrude Stein Has Arrived: The Homecoming of a Literary Legend (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019). As a boy Morris watched countless World War II movies and television shows with his father, former private Roy Morris of the 79th Division, who counted Battleground (1949) and Patton (1970) among his favorite films. Robert O. Hogan, also referred to in this story, was the father of Bill Hogan, MHQ’s editor.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Race to the Rhine

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!