Monica Mohindra On July 27, 1953, the Korean War ended with an armistice but no official treaty, technically meaning a state of war still exists between the combatant nations. Among the multinational participants in that significant flare-up in the Cold War were nearly 7 million U.S. military service personnel, of whom more than 1 million are still living. The 70th anniversary of the armistice spurred the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project to redouble its efforts to record for posterity the memories of those participants while it still can. Military History recently interviewed Veterans History Project director Monica Mohindra about its collection, the pressure of time and ongoing initiatives to honor veterans of that “Forgotten War” and all other American conflicts.

What is the central mission of the Veterans History Project?

Our mission is to collect, preserve and make accessible the first-person remembrances of U.S. veterans who served from World War I through the more recent conflicts. We want all stories, not just those from the foxhole or the battlefronts, but from all veterans who served the United States in uniform. The idea, developed by Congress in October 2000, was to ensure we would all be able to hear directly from veterans about their lived experience, their service, their sacrifice and what they felt on a human scale about their participation in service and/or conflict.

Is your recent emphasis on the ‘forgotten’ Korean War mainly due to the anniversary?

Correct. But there is so much to share from the history of the Korean War that is relevant. We’re also marking the 75th anniversary of the desegregation of the U.S. military, and researchers have been using our collections to understand, for instance, nurses’ perspectives on what it was like to serve in a desegregated military. Our collection speaks to what it was like prior to and after desegregation.

To what extent do memories tied to both anniversaries overlap?

One of the real strengths of the Veterans History Project, and of oral history projects in general, is that one can pull generalized opinions from a multiplicity of voices. For example, there’s a story about a veteran named James Allen who “escaped” racially charged Florida to join the military. Serving in Korea in various administrative tasks, he experienced a taste of what life could be like under desegregation. When he returned to the United States, he moved back to Florida, the very place he’d escaped, to help veterans and advance such notions.

You’re the spouse of a Navy veteran. Does that shape your perspective on history overall and the project you’ve taken up?

It absolutely adds another layer to the Veterans History Project and what it means on a human scale. This is personal. My husband’s experience, just like each veteran’s, is unique. He’s not ready to share his story—maybe not with me ever. His father, who also served, is not ready to share his story—maybe not with me, maybe not ever. Both of his grandfathers served. My grandfather served, too. So, I feel a personal imperative to help those veterans who are ready to share their stories.

It’s that seriousness of purpose, to create a private resource for future use, the Veterans History Project offers individuals around the country. We already have more than 115,000 such individual perspectives, and that gives us the opportunity to share the wealth of these collections.

How does the project handle contributions?

Individuals may want to start by conversing with the veterans in their lives or by finding the collection of a veteran.

To what use does the project put such memories?

People use the Veterans History Project—often online and sometimes in person here at the Folklife Center Reading Room—for a variety of reasons. More than 70 percent of our materials (letters, photographs, audio and video interviews, etc.) are digitized, and more than 3 million annual visitors come to the website. They’re using our materials for everything from school projects to enlivening curricula. Recently researchers have conducted postdoctoral research on desegregation during the Korean War. The project is also useful for beginning deeper conversations among friends and family members.

In this time of AI [artificial intelligence], the collection is a primary resource from those who had the lived experience. What did they hear? What did they see? How did they keep in touch with loved ones? These are the kind of questions we pose.

What was unique about the Korean War experience?

Perhaps the extraordinary scope of injuries service members suffered because of the cold. Consider the Borinqueneers [65th U.S. Infantry Regiment], out of Puerto Rico, many of whom had never seen snow. On crossing the seas, they arrived in these extreme conditions, and it’s all so foreign. They received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2014, and we are fortunate to have memories from 20 Borinqueneers in our collection.

Recently, the last American fighter ace of the Korean War died. Are you concerned about the time constraints you face?

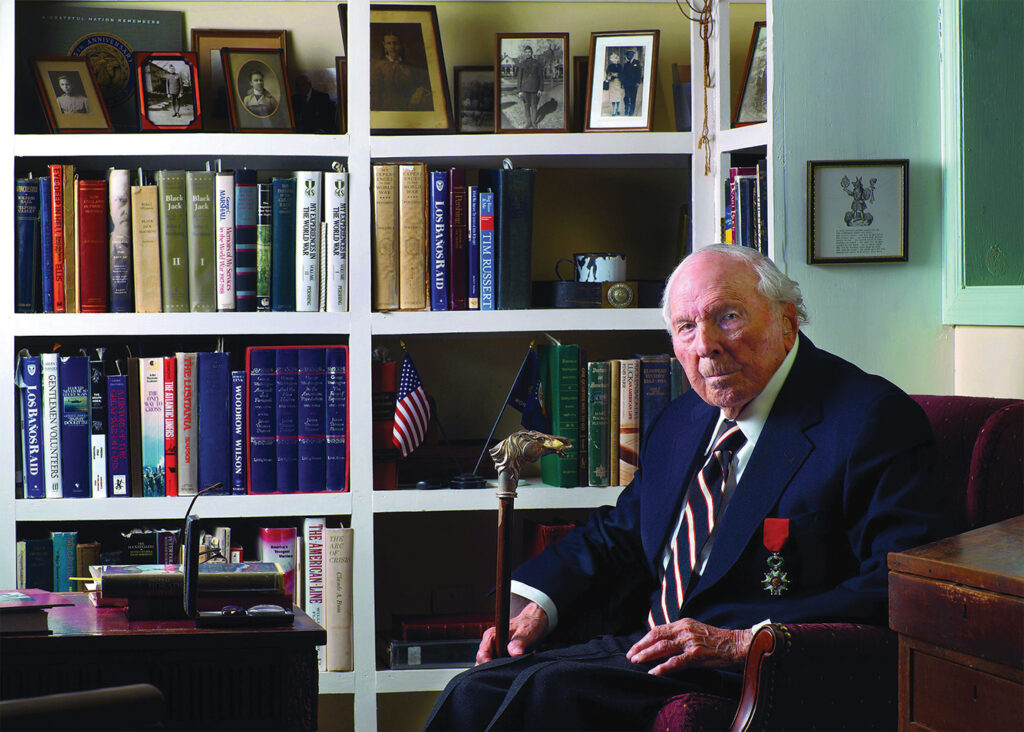

Yes. The weight of that actuarial reality was quite heavy on World War I veterans. We had the pleasure to work with Frank Buckles [see “Frank Buckles, 110, Last of the Doughboys,” by David Lauterborn, on HistoryNet.com] several times, and he became sort of an emblem of his cohort, if you will. That was a heavy weight on him, one that he did not shy from.

The burden now is on people like me, you, your readers, to make sure we do sit down with the veterans in our lives. We want people 15 and up to think about doing that.

What about the memories of U.N. personnel from other nations who served in Korea?

The legislation for the Veterans History Project is very clear. It limits our mission to those who served the U.S. military in uniform. That does include commissioned officers of the U.S. Public Health Service, an often forgotten uniformed service. We cannot accept the collections of Allies who served alongside U.S. troops. However, we do collaborate with other organizations within our sphere. For instance, in cooperation with the Korean Library Association we held an adjunct activity at the Library of Congress, a two-day symposium.

Do you accept contributions from Gold Star families?

We do. The legislation for the Veterans History Project was amended in 2016 with a new piece of legislation called the Gold Star Families Voices Act. Before that we accepted collections of certain deceased members, including photographs or a journal, diary or unpublished memoir that could capture the first-person perspective.

However, the 2016 legislation put a fine point on a definition for Gold Star families to contribute. Under the Gold Star Family Voices Act, those participating as either interviewers or interviewees must be 18 or older, as one is speaking about a situation that involves trauma. Our definition calls for collections of 10 or more photographs or 20 or more pages of letters or a journal or unpublished memoir. The other way to start a collection is to submit 30 or more minutes of audio or video interviews. This enables us to gain a full perspective of a veterans’ experience, whether they are living or deceased.

Where can an interested veteran or family member get more information?

There is all sorts of information on our website [loc.gov/vets]. They should also feel free to come to our information center at the Library of Congress [101 Independence Ave. SW, Washington, D.C.], with extended hours on Thursdays until 8 p.m.

This interview appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.