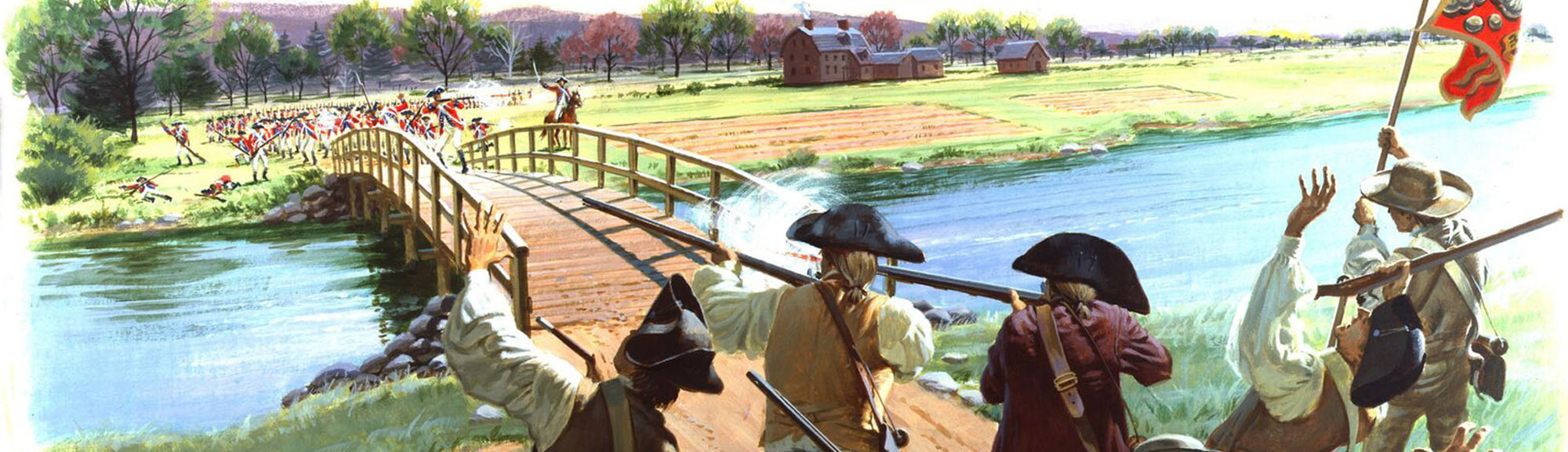

ON APRIL 19, 1775, rebellious colonials exchanged musket fire with British soldiers on Lexington Green and at Concord’s North Bridge. A separate conflict immediately followed the fighting in those Massachusetts towns. Both sides, now using words as weapons, sought to sway public opinion. The storytelling mattered, but the speed of delivery mattered even more. Whoever first presented convincing evidence to justify or condemn armed rebellion, claim responsibility or assign blame, and cement in the public mind how each contingent fared in the skirmishes stood to sway the hearts and minds of officials and the publics in the American colonies and in Britain.

Sentiment in the colonies varied regarding British governance. Many colonists were loyal to King George III. In Britain, moderates sympathized with fellow British subjects in North America. Rebel leaders needed to distribute their edition of the events of April 19 to the American colonies, to England, and across Europe before the king’s men at home and abroad could propagate a counternarrative.

The rebels, hoping to rally support, aimed to stress grievous actions by the king’s troops against citizens of Lexington and Concord—and to get that pro-rebel perspective before those key audiences. The loyalist message, particularly as developed by General Thomas Gage, commander of British troops in America, stressed the colonists’ unreasonableness and barbarity in triggering the famous exchanges of fire and subsequent attacks on British soldiers as they retreated to Boston.

In Boston, General Gage immediately had his intelligence and information staffs prepare reports on the events, but the copy that Gage provided to the local press was apparently not hard-hitting. The Boston News-Letter and other loyalist papers carried articles saying that colonists’ and British military reports of the April 19 events were so at odds with one another as to preclude publishing clear accounts. Loyalist publishers did reproduce a warning from Gage that a colonial delegate assembly set to convene in Philadelphia to discuss the conflict would be doing so “without his Majesty’s Authority.”

Gage ordered a broadside prepared for military authorities at home and the court in London describing his troops’ actions against rebel colonists. The general dispatched HMS Sukey—described as a “frigate,” perhaps meaning an armed transport displacing 200 tons—with orders to deliver his account to Lord Dartmouth, secretary of state for the colonies. Gage wanted to convince the court, the British public, and other European nations that the rebels had acted rashly and without just cause. The Sukey cast off from Boston on April 24.

Each colony had a Committee on Safety, local leaders whose job was to discuss and publicize issues, monitor royal actions, and muster the militia. By 11 o’clock on the morning that fighting erupted at Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts Committee on Safety, on the run, had met with committeeman Joseph Palmer. Members assigned Palmer to sum up that morning’s events in a message to be couriered around the colonies. Drafting a dispatch by hand, Palmer recruited professional post rider Israel Bissell, 27, to spread the news as quickly as possible.

Bissell, from Suffield, Connecticut, rode as part of a rudimentary horse-powered postal system that dated to the early 1700s. Midway between Watertown and Worcester, the courier’s mount collapsed; he procured another and pressed on.

Shouting “To arms, to arms, the war has begun!” Bissell delivered the Lexington Alarm, as the dispatch came to be known, to five towns in Massachusetts and Connecticut. The dispatch Bissell carried read, in part, “To all friends of American Liberty be it known that this Morning before break of day a Brigade consisting of about 1000, or 1200 Men landed at Phip’s farm at Cambridge and Marched to Lexington, where they found a company of our Colony Militia in Arms upon whom they fired without any provocation, and killed 6 men and wounded 4 Others. By an express from Boston we find that another Brigade are now upon their march from Boston supposed to be about 1000. The bearer, Israil [sic] Bissell, is charged to alarm the Country quite to Connecticut, and all persons are desired to furnish him with fresh Horses, as they may be needed. I have spoken with Several who have seen the dead and wounded. Pray let the Delegates from this colony to Connecticut see this.”

Each town receiving the word treated the bulletin in the customary way. By hand, scriveners reproduced the original. Members of each local Committee of Correspondence—the rebels’ political arm—endorsed every fair copy. Riders took the certified copies to more towns. From Bissell’s stops in Massachusetts and Connecticut, unnamed riders spread copies west to Springfield, east to Rhode Island, north to New Hampshire, south to Virginia, and points beyond. By midday April 21, this process had brought the news to New Haven, as well as towns along the Connecticut coast. By April 23, New York City and Morristown, New Jersey, had gotten the word; by April 24, New Brunswick, Trenton, and Philadelphia. Riders galloped on, alerting Baltimore and Annapolis and reaching Williamsburg April 29. Soon a rebel narrative of the Lexington and Concord battles had begun taking root in the colonies, further stirring insurrection.

To shore up the story that the British had fired first at Lexington and at Concord, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress convened the morning of April 22 in Concord, resuming that afternoon in Watertown to be nearer an impromptu patriot army assembling in an arc around Boston. The Provincial Congress voted to take depositions from witnesses and to record these affidavits for publication in colonial newspapers as well as for transmission to Britain. Some papers and circulars with a pro-rebel bent reported the affidavits’ contents in a measured manner; others embellished. One broadsheet claimed that while marching back to Charlestown and Boston, the redcoats, “not content with shooting the unarmed, aged and infirm…disregarded the Cries of the wounded, killing them without Mercy and mangling their Bodies in the most shocking Manner.”

Even more urgent than alerting colonists was the need to communicate the patriot point of view in Britain. Convincing Britons that the rebels had a valid cause could counterbalance whatever Gage said. “The hot, tumultuous April day of blood was scarcely over before the more sagacious of the Patriots about Boston were planning how to make the most of the new situation,” Robert S. Rantoul, descendant of an Essex, Massachusetts, colonial family, wrote in 1900. “It was their first care to show that they were within the law; not the aggressors—not disturbers of the peace of the realm, but champions of the rights of Englishmen.”

For British eyes, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress packaged the most incendiary material available. “We are at last plunged into the horrours of a most unnatural war,” the cover letter read. “Our enemies, we are told, have despatched to Great Britain a fallacious account of the tragedy they have begun; to prevent the operation of which to the publick injury, we have engaged the vessel that conveys this to you as a packet in the service of this Colony, and we request your assistance in supplying Captain Derby, who commands her, with such necessaries as he shall want.”

“Captain Derby” was John Derby, 34, son of an Essex shipping family. His older brother Richard served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, which directed that he pick a captain and vessel and speed a stack of rebel documents to Britain. Richard had John (see “Derby’s Days,” p. 55) outfit the family’s fast schooner Quero and make for London, there to hand the materials to Benjamin Franklin, colonial representative to the Crown.

Along with the letter were packaged the Salem Gazette’s April 21 and April 25 editions. The paper had reported on the battles, sworn affidavits about them from colonists and British prisoners, and a letter from the Provincial Congress that began, “FRIENDS AND FELLOW SUBJECTS: Hostilities are at length commenced in this colony by the troops under the command of general Gage, and it being of the greatest importance, that an early, true and authentic account of this inhuman proceeding should be known to you, the Congress of this colony have transmitted the same, and from want of a session of the honorable Continental Congress, think it proper to address you on this alarming occasion.”

The packet interwove sober first-hand accounts, hyperbole, and hearsay. Of the king’s soldiers’ conduct on their 20-mile post-skirmish march back to Charlestown, a correspondent wrote, “a great number of the houses on the road were plundered and rendered unfit for use; several were burnt; women in childbed were driven, by the soldiery, naked into the streets; old men, peaceably in their houses, were shot dead, and such scenes exhibited as would disgrace the annals of the most uncivilized nation.”

Derby and crew needed time to make the 62-ton Quero shipshape for an Atlantic crossing. By April 28, the schooner was ready. Orders from the Provincial Congress in hand, Derby and his men sailed Quero, empty but for ballast and that stack of newspapers, affidavits, and letters, out of Salem harbor.

The race, a 3,230-mile haul, was on. Even four days behind Sukey, Derby’s lithe schooner would give the lumbering frigate a run for its money—provided Derby evaded the Royal Navy frigate HMS Lively, patrolling off Salem. However, Derby crews had been running in and out of that harbor and along the Massachusetts coast for decades. Quero reached the open sea without incident.

The Provincial Congress had directed Derby to keep his mission “a profound secret from every person on earth.” To avoid capture and discovery of the materials, he was to land at Dublin, Ireland, then cross the Irish Sea to Scotland and proceed overland to London. Derby instead made straight for the English Channel, crossing unimpeded in four weeks.

Landing on the Isle of Wight in the Channel, Derby told his first officer to sail to Falmouth, at the tip of Cornwall and nearly 300 miles from London, and wait for him. Carrying the secret papers and unaccompanied, Derby boarded a ferry for Southampton, where he hired an enclosed horse-drawn coach to take him the 75 miles to London. Arriving in the British capital on May 28, Derby, learning that Franklin had departed for Philadelphia, handed the information package to Arthur Lee, a correspondent of Samuel Adams. “Together, Derby and Lee enlisted the aid of John Wilkes…an ‘eccentric and fearless radical,’ who was the Lord Mayor of London and a strong supporter of the colonies,” historian Walter Borneman wrote. “[B]y the following day—thanks in part to some well-placed whispers by Wilkes, most informed citizens…had been introduced to the rebel version of events.”

His duty done, Derby traveled by public coach through Portsmouth to Falmouth, where Quero waited. Derby sailed the schooner, still carrying only ballast, back to Salem. On July 18, he appeared at General George Washington’s headquarters in Cambridge to inform Washington that “the news of the commencement of the American war threw the people, especially in London, into great consternation, and…that many there sympathized with the Colonies.”

As Gage’s official report was creeping across the Atlantic aboard Sukey, Lord Dartmouth learned of the insurgent narrative that Derby, Lee, and Wilkes had begun disseminating. With no counterpoint to offer, all the colonial secretary could do was try to allay Britons’ anxiety. In the May 30, 1775, Gazette, a Crown publication, Dartmouth wrote, “A report having been spread, and an account having been printed and published, of a skirmish between some of the people in the Province of Massachusetts Bay and a detachment of His Majesty’s troops, it is proper to inform the publick that no advices have as yet been received in the American Department of any such event. There is reason to believe that there are dispatches from General Gage on board the Sukey…which, though she sailed four days before the vessel that brought the printed accounts, is not arrived.”

It vexed Dartmouth to be emptyhanded as the rebel account caromed around Britain. In a June 1 letter to Gage, the secretary wrote, “[I]t is very much to be lamented, that we have not some account from you of the transaction.” Gage got much the same reproach from Thomas Hutchinson, loyalist governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, who happened to be visiting London. Derby’s communiqué “caused a general anxiety in the minds of all who wish the happiness of Britain and her Colonies,” the governor lamented. “It is unfortunate to have the first impression made from that [the rebels’] quarter.”

Not until June 9, 1775, did Sukey reach Portsmouth, 12 days after Quero docked. On June 10, a naval attaché handed Lord Dartmouth Gage’s dispatch. On June 12, the London Press reported, “The Americans have given their narrative of the massacre; the favourite official servants have given a Scotch [skimpy] account of the skirmish.” Dartmouth rebuked Gage for deploying the sluggish Sukey and blamed the general for allowing the rebel narrative to stir negativity at home by creating “an impression here by representing the affair between the King’s troops and the rebel Provincials in a light the most favorable to their own view. Their industry on this occasion had its effect, in leaving for some days a false impression upon people’s minds, and I mention it to you with a hope that, in any future event of importance, it will be thought proper, by both yourself and the admiral, to send your dispatches by one of the light vessels of the fleet.”

A Vienna correspondent for the New York Gazette and Mercury summed up the race between Quero and Sukey: “Captain Darby’s [sic] ship, which brought over the printed account, is a small vessel of about 60 tons, schooner rigged, and quite light; and the ship Sukey is a large ship, about 200 tons, and heavily loaded to a capital house in the Boston trade. These circumstances may very well account for the difference of time between the arrival of the two ships.”

Derby’s trans-Atlantic coup presaged other rebel public relations triumphs. Applauding a hometown hero’s valor and quick thinking, the Essex Gazette reported in its July 21, 1775, edition, “That our Friends increased in Number; and that many who had remained neuter in the Dispute, began to express themselves warmly in our Favor.” Sentiment favoring the colonists strengthened in Britain and Europe, gaining the rebels important friends and allies. In Britain, recriminations against that nation’s military became rife. Collectively these factors sapped popular support for King George III’s North American cause. The race to inform England and its colonies went to the Americans thanks to crisp planning, effective communications, and derring-do, a contrast to Gage’s plodding information campaign. The British general and his subordinates were casual, if not cavalier, about presenting their version of events at Lexington and Concord to their most important audiences.

After returning to Salem, John Derby asked the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts to cover the costs of the voyage, totaling 57 pounds, eight pence. As for his labor, the final line of his expense report read, “To my time in Executing the Voige [sic] from hence to London & Back—0.”