Every spring the National Pony Express Association attempts a scrupulously authentic reenactment of the legendary cross-country mail ride linking St. Joe on the wide Missouri with the California state capital of Sacramento. But as no one is entirely sure exactly what happened on April 3, 1860 — or for the rest of the 78 or so weeks the Pony Express crossed the West — scrupulous authenticity is something of a problem. The run, of nearly 2,000 miles, is longer, its reenactors always stress, than the fabled Iditarod dog-sled race, but they don’t have to deal with Alaska’s cold. And they also avoid snow. Since there is still too much snow in much of the West at the beginning of April, the Pony re-rides are held in June.

The Pony Express was in business of one sort or another between April 3, 1860, and October 26, 1861. Purists like to tweak that ending date, noting that mailbags — called mochilas — were still in transit into November. But for all practical purposes ‘our little friend the Pony,’ as the Sacramento Bee called it, ran no more after the transcontinental telegraph was completed on October 24, 1861.

The story of the Pony Express is a bit like the story of Paul Revere’s ride — an actual historic event, rooted in fact and layered with centuries (a century and a half in the Pony’s case) of fabrications, embellishments and outright lies. In the mid-20th century, William Floyd, one of a legion of amateur historians to delve into the tale of the Pony Express, threw up his hands and observed, ‘It’s a tale of truth, half-truth and no truth at all.’ He was right on each account.

The business was called the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company, a name too cumbersome to appear on anything. The company’s mail service across America in 1860 and 1861 became known as the Pony Express, a legend in its own time. Americans living on the Pacific slope in the newly minted state of California, drawn there by the Gold Rush, were desperate for news of home. The Pony Express dramatically filled that gap by promising to deliver mail across the country from the end of the telegraph in the East to the start of the telegraph in the West, in 10 days time or less. Normal mail, brought overland or via ship, took months. The term ‘pony express’ had been used before, and, indeed, Americans had transmitted information on the backs of fast horses since colonial times. Historians of mail service always note that Genghis Khan used mounted couriers.

It was from the first a madcap if wonderfully romantic idea. Well-mounted light fellows (Mark Twain called them ‘little bits of men, brimful of spirit’) would, by using a series of fresh horses and relief stations, cross wild and largely uninhabited expanses from Missouri to the far coast.

The firm that bankrolled the Pony — and the term bankrolled must be used very lightly, for the venture hemorrhaged money from day one — was Russell, Majors & Waddell. Household names in their heyday on the frontier, William Hepburn Russell, Alexander Majors and William Bradford Waddell had made their reputation hauling freight to military outposts. Their business may very well have been broke when the Pony Express started (the result of massive losses incurred freighting during the so-called Mormon War of the late 1850s), but no one appears to have known that. The firm’s reputation and the chutzpah of its primary spokesman, Russell, got things rolling.

The business — which originally intended to cross the west once a week, moving important mail on horseback — was not a financially sound venture. Russell, Majors & Waddell spent a great deal of money on horses and dozens of way stations, which were required every 10 to 15 miles depending on the terrain. They also had to hire riders and station tenders. East of Salt Lake City, the Pony Express appears to have piggybacked on existing overland stage operations, but west of the Mormon Jerusalem, things got a little dicey. It was expensive and complicated to operate such a venture. In many parts of the country, water had to be hauled considerable distances. And even at the initial rate of $5 a half ounce (later reduced), there was no way that a mochila, which held only 20 pounds of mail, could possibly carry enough correspondence to make this line pay. Its patrons were the government, newspapers, banks and businesses. The average person did not often send letters via Pony Express. We are dependent on notices that appeared in the California newspapers at the time announcing the arrival of the Pony and what mail it was carrying. Often the mochila contained only a couple of dozen letters. Considering how many riders and way station keepers had been involved in moving those letters from St. Joseph, Mo., the venture rates as one of the most fabled failed businesses in American history.

No sooner had the Pony Express begun than the Paiute War (or Pyramid Lake War) shut the line down in much of what today is Nevada and Utah. That war halted service from early May 1860 into July of that year and made travel in the region risky into October. Stations burned by the Paiutes had to be replaced, and the often overlooked war reportedly cost Russell, Majors & Waddell $75,000. To make up for lost business, the Pony started moving mail more than once a week, twice on average. But the Civil War came along, and Edward Creighton and his associates completed the transcontinental telegraph in unexpectedly fast time. That put the Pony down for good.

Most chroniclers of the story of the Pony Express have been little interested in how this’saga of the saddle,’ as one enthusiast called it, became what is in essence an American tall tale. Much of that is easily explained by the odd chronology of the tale. The Pony Express was short-lived and its financial collapse essentially ruined its backers. If Russell, Majors & Waddell left significant records, those have never been discovered. One explanation is simply that they did not keep many records; the other is that they destroyed whatever records they had to avoid creditors. Both Russell and Waddell died within a decade of the end of the Pony Express and never wrote a word about their exploits. Majors, an honest-to-God pioneer in western freighting on the fabled Santa Fe Trail, survived. But Majors, a simple man who was a devout Bible reader, did not compose his memoirs until the end of the 19th century. When he did, his life story was ghostwritten or at least heavily edited by Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, a fabled dime novelist and hack. William ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (we will return to Buffalo Bill anon) paid Rand McNally to print this hodgepodge of recollections — Seventy Years on the Frontier: Alexander Majors’ Memoirs of a Lifetime on the Border. Majors later complained that Colonel Ingraham had taken liberties with the story.

Despite the best efforts of enthusiasts, we are not even sure exactly who rode for the Pony Express. Majors said that he had 80 men in the saddle, but this was not the modern American space program. It seems plausible, and many personal anecdotes support this theory, that just about anyone could ride for the Pony if they were available and the Pony needed a rider. Dramatic images (and every painter in America from Frederic Remington to those who wished to be Remington painted the Pony Express) always show a rider at full gallop pursued by Indians or desperadoes. But the few remaining riders who were actually interviewed late in their lives never mentioned Indians or desperadoes. They always complained about the weather, understandable if you were riding a horse across western Nebraska or Wyoming in January at night in a snowstorm. They also complained bitterly about not being paid. Russell, Majors & Waddell were notorious deadbeats. Wags in the American West claimed that the initials C.O.C.& P.P. actually meant ‘clean out of cash and poor pay.’

The first chronicler of the Pony Express was Colonel William Lightfoot Visscher, a peripatetic newspaperman (but not a colonel) who drifted across the American West in the late 19th century. He is, on reflection, a perfect chronicler for such a tale. He never let the facts get in the way of anything he wrote. Visscher’s book A Thrilling and Truthful History of the Pony Express was published in 1908, nearly half a century after the Pony Express went out of business. Anyone wondering how the story of the Pony Express became muddled need only consider that it took half a century to write a book about the subject, and its author was a dubious chronicler.

Much of Visscher’s research appears to have been conducted at the bar of the Chicago Press Club, his legal address for many years. A terrible liar, a drunkard, a bad poet and a rascal, Visscher bore an amazing resemblance to comedian W.C. Fields. The colonel was a delightful if completely unreliable historian. We have no idea where he got most of his information, although he appears to have cribbed a fair bit of it from the few early attempts to set down some facts about the Central Overland. Historians of the Pony, such as there have been, have always ignored this jolly old lush, who drank two quarts of gin a day for much of his life but lived to be 82.

Five years after the colonel took up his pen, along came Professor Glenn D. Bradley at the University of Toledo. The professor did not do much to help the story either, and then he went and got malaria while having a Central American adventure and died. Bradley does not even mention Visscher or his book in his own effort, The Story of the Pony Express: An Account of the Most Remarkable Mail Service Ever in Existence and Its Place in History. It is possible that he never even read Visscher’s work.

After Bradley’s 1913 book, there was a period of dormancy in Pony Express scholarship for some years. But then came several other books, also long on embellishment. Some of them, such as Robert West Howard’s Hoofbeats of Destiny, are full of interesting details but also use fictional characters to drive the story. This does not help sort out the fact from the fancy.

Shakespeare tells us ‘old men forget,’ and the bard was so very right in the matter of the Pony Express. It was well into the 20th century before anyone tried to interview any of the remaining old riders. They either remembered nothing of significance or their memories were fabulous, resulting in wild stories in which the Pony just got bigger and bigger each year in the retelling.

Raymond and Mary Settle made one of the few serious attempts to write a Pony Express history. Their 1955 book Saddles and Spurs: Saga of the Pony Express provides a solid overview but does not consider how the story of the Pony Express came to be. They also failed to recognize that Russell, if not the other owners of the firm, was a con man and rascal of the worst sort. They make no mention of Colonel Visscher, either. Raymond Settle, a Baptist minister, left his papers to William Jewell College in Liberty, Mo. They remain, unsorted and uncataloged, in dusty boxes in the cellar of the college’s library.

|

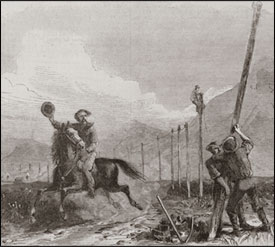

| A Pony Express rider makes a friendly gesture toward men putting up a telegraph line, in a wood engraving (from a painting by George M. Ottinger) that appeared in the November 2, 1867, Harper’s Weekly. The completion of the transcontinental telegraph on October 24, 1861, actually cost such riders their jobs (Library of Congress). |

The greatest proponent of the Pony Express story in modern times was William Waddell, the great-grandson of William Bradford Waddell. The Pony’s Waddell was actually a mousy bookkeeper who stands in the shadow of cohorts Russell and Majors. But his descendant decided that a spot of revisionism was in order. He obtained the copyright to Professor Bradley’s little book and reissued it in 1960 with his own annotations. There is no mention that it was actually Bradley’s book. What Waddell apparently liked most about Bradley’s account was how it pretty much ignored Alexander Majors, the real hero of the Pony Express, who lived until 1900.

The Pony Express story’s tremendous growth through the years can be explained in no small part by the wonderfully eccentric cast of characters who attached themselves to the tale from its beginning. One of the first was Captain Sir Richard Burton, the British explorer. Burton went down the line of the Pony Express in the summer and fall of 1860, the first credible eyewitness to the venture. A seasoned military man, he took copious notes, and after spending a mere 100 days in the American West produced a 700-page account of his adventures, City of the Saints. Burton provides us with the best solid information we have about conditions along the line. One year later, while Burton was writing his account in London, no less a chronicler of America than Mark Twain appeared on the scene.

The man who would become Mark Twain was merely Sam Clemens, a 25-year-old recent deserter from the Confederate Army when he ran into the Pony Express. Clemens had gone West in a Concord coach with his brother Orion, who was on his way to be secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada. Like Burton, the brothers left from St. Joe, probably from the Patee House, headquarters of the Pony Express. One day in the first week of August 1861 in western Nebraska Territory, near Mud Springs, Sam Clemens saw a Pony Express rider. His description is one of the most powerful bits of eyewitness testimony we have:

Presently the driver exclaims: ‘HERE HE COMES!’

Every neck is stretched further, and every eye stretched wider. Away across the endless dead level of the prairie a black speck appears against the sky, and it is plain that it moves. Well, I should think so! In a second or two it becomes a horse and rider, rising and falling, rising and falling — sweeping towards us nearer and nearer — growing more and more distinct, more and more sharply defined — nearer and still nearer, and the flutter of the hoofs comes faintly to the ear — another instant a whoop and a hurrah from our upper deck, a wave of the rider’s hand, but no reply, and man and horse burst past our excited faces, and go winging away like a belated fragment of a storm! So sudden is it all, and so like a flash of unreal fancy, that but for the flake of white foam left quivering and perishing on a mail sack after the vision had flashed by and disappeared, we might have doubted whether we had seen any actual horse and man at all, maybe.

Twain’s encounter with the Pony Express — he probably saw one rider — took all of two minutes. But writing from memory and without notes a decade later in Hartford, Conn., he got two whole chapters in Roughing It out of the experience, which shows you what you can do with your material if you are Mark Twain. While Burton loathed the West, complaining nonstop of fleas and flies and filth and Indians and stupid Irishmen, Twain had a grand time. But both writers left us a lot of solid information — what sort of food the men ate, the clothing they wore and descriptions of the stations, most of which were hovels — that is not available anywhere else.

Buffalo Bill Cody (1846-1917), though, is the reason Americans remember the Pony Express today. In essence, Buffalo Bill saved the memory of that enterprise. Long before there were books about the Pony Express, let alone motion pictures, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West presented the Pony Express rider — a fixture in Cody’s extravaganza from the day it opened in Omaha, Neb., in 1883 until the day it closed in 1916.

Not only Americans became dramatically acquainted with the Pony Express through Buffalo Bill; Europeans from penniless orphans in London (let into the show because of kind-hearted Cody) to Queen Victoria, Kaiser Wilhelm and the pope in Rome had the same pleasure. Part of Cody’s enthusiasm for celebrating this bit of the Wild West was that in his youth, he had actually known Alexander Majors. After Cody’s father died, Majors gave the boy (who was about 11 at the time) a job, riding a pony or a mule as a messenger for the freight-hauling firm. Never shy of embellishing his past, Cody always claimed to have ridden for the Pony Express — and ridden the longest distance, too! That claim, however, like so many of his yarns, is highly dubious (see accounts of his alleged Pony adventures in a related story, P. 38). The best examination of his boyhood, undertaken by a forensic pathologist with an interest in history, would seem to indicate that Cody never sat in the saddle for the Central Overland. He did, however, do a great deal for the memory of the Pony Express. Without his devotion, it is unlikely that anyone would remember the horseback mail service. Because of Buffalo Bill, people who did not speak a word of English knew what the Pony Express was. Even today there are Pony Express clubs in Germany and Czechoslovakia, reminders of Buffalo Bill’s legwork on behalf of the fast mail.

Students of the story of the Pony Express will note that its memory waxes and wanes. In about 1960 on the occasion of its centennial, the memory was sweetened when the Eisenhower administration (Ike was from Kansas, Pony Express country) festooned the West with historic markers recalling the days of saddles and spurs. Many western towns boast ‘authentic Pony Express stations,’ but the provenance of those shrines is best left unexplored. Like so much of the memory of the Pony Express, the more one knows about the story, the more fractured and fabulous it becomes. There is hardly a gift shop or historic shrine between Old St. Joe and Old Sac that does not sell an ‘authentic’ Pony Express rider recruiting notice.

The company recruited daredevils, placing eye-catching notices in the St. Louis and San Francisco newspapers that read: ‘Wanted. Young, Skinny, Wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25.00 per week.’ Alas, it appears that this memorable ad was the work of an early 20th-century journalist writing in the Western magazine Sunset.

In the 1920s, a remnant of what had been the U.S. cavalry in California tried to reenact a bit of the ride as a kind of exercise and found it too difficult. Frankly, in the 21st century we do not have horsemen or women who can ride like that any longer. Men are not born in the saddle now, and even the most accomplished modern equestrian could not take the mochila from Fort Churchill to Robbers Roost.

The annual reenactment is a wonderful thing to witness. To stand on the edge of a rain-soaked field in central Nebraska and see the lone figure of a man on a galloping horse appear on the distant horizon is still a stirring sight. It is the sight that inspired Mark Twain so long ago. It is the memory that Buffalo Bill Cody loved.

Hollywood has always been especially kind to the memory of the Pony Express. As might be expected, just about all references to it in film (and there were silent films as early as the turn of the last century featuring the Pony Express) are wrong. The entertaining 1953 Paramount movie The Pony Express has Charlton Heston as Buffalo Bill teaming up with Wild Bill Hickok (played by Forrest ‘F Troop’ Tucker) and heading to ‘Old Californy’ to start the Pony Express. There is not a shard of fact in the entire film. (Hickok actually worked for the firm but merely as a stock tender in Nebraska.) Several years ago, the film Hidalgo featured a wild tale of Frank Hopkins, a self-proclaimed equestrian who said that he rode for the Pony Express. Hopkins’ Arabian adventures showcased in the movie are fantasy (see the full story in the October 2003 Wild West), and let it further be said that Hopkins most likely wasn’t even born when the real Pony riders were hitting the trail.

The memory of the Pony Express remains sweet. In the years in which I attempted to follow its trail, I met dozens, perhaps hundreds of Americans, who believe that their great-great-grandpas rode for the Pony, as the old-timers in the West still affectionately call it. There are so many people out there with ancestors who rode for the Pony that Russell, Majors & Waddell would not have needed to buy expensive horses but could have lined up all the riders so that the mail passed hand to hand all the way from St. Joseph to Sacramento.

A cursory examination of early 20th-century newspapers in the American West will amply illustrate that they regularly reported the death of the last Pony Express rider. The Tonopah Bonanza reported it on April 3, 1913, with the death of 76-year-old Louis Dean. A year later the same newspaper reported that another ‘last of the Pony Express riders’ was gone. This time he was Jack Lynch. The Reno Evening Gazette frequently dusted off the story, one of the best being the news of the death of James Cummings, the last of the Pony Express riders, dead at age 76 on March 3, 1930. He would have been riding for Russell, Majors & Waddell at age 6 or 7.

Broncho Charlie Miller, charming but no doubt full of beans, was the last man to claim the title of ‘last of the Pony Express riders.’ When the old boy died at Bellevue Hospital in New York City on January 15, 1955, ‘the brotherhood of the Pony Express riders wound up its affairs’ as one obituary put it. Miller was a delightful end piece to the story of the Pony Express. He claimed to have been born on a buffalo robe in a Conestoga wagon going west in 1850. His claims to have ridden for the Pony — a run that would have taken him up from Sacramento over the Sierra Nevada and down into Carson City, Nev. — were lively. He would have been 10 or 11.

A former rider and showman with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (that part is true), Miller was the king of ‘the Last of the Pony Express riders.’ A charming rascal and shameless self-promoter who had Old West written all over his face and attire (and that played best in the East), Miller was a chain-smoking, hard-drinking admitted horse thief. But America forgave him. Pony Express purists and doubters regularly challenged the old boy, but they never laid a glove on him. He refused to even acknowledge that there were purists and doubters of his tales. America loved Broncho Charlie Miller, whether he was telling the truth or not. He was, in the words of The New York Times, ‘the incarnation of the Old West for thousands of delighted youngsters — and some folks not so young.’

When Miller was an old man — 82 if we believe his birth date — he rode an old horse named Polestar from New York City to San Francisco to remind America, lest it forget, that the Pony Express had once brought the mail. People stood in the streets and cheered to see the old man loping along. He took a crazy, circuitous route that did not follow the route of the Pony Express and rode hundreds of miles into the Southwest. Go figure.

Despite all the rascals and scamps associated with the story of the Pony Express, admirers of the bold venture will be cheered to learn that there were actual heroes. One of those was Robert Haslam, or Pony Bob, a legendary fast mail rider in the real 19th-century American West. An Englishman who came to Utah as a teenager at the time of the Mormon migration, Haslam rode for the Pony in Nevada at the time of the Paiute War, making a fabled ride of nearly 400 miles without relief. He later rode express mail for Wells, Fargo & Co., elsewhere in the West and was long associated with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but Haslam died in a cold water flat on the south side of Chicago in 1912, forgotten. Haslam was the real deal. We have a vivid eyewitness account in the Territorial Enterprise, the newspaper where Mark Twain cut his teeth, of a race on the Fourth of July in 1868. This account leaves no doubt that Haslam was a fabled Pony Express rider in his day and that he was a great horseman.

Another of those Americans who helped to save the true story of the Pony Express, or at least as true as it could be, was Mabel Loving. Mrs. Loving was an amateur poetess in St. Joseph. She was a terrible poet but a prolific one, as bad poets often are (Colonel Visscher was a prolific bad poet, too).

Just before World War I, Mabel Loving did something that no one had thought to do. She sat down and began to write to the few surviving members of the Pony Express. Her correspondence with those riders provides us with some of the richest detail we have about that mail service. Loving’s work was a labor of love, and she provided in her will that her little book on the Pony Express be published (no commercial publisher would touch it). Today, if you can find a copy of The Pony Express Rides On! you will pay dearly for it. Imperfect as it is — the printer appears to have actually lost two chapters — it contains some fascinating information about a fabulous time when young men on fast horses could cross the West in 10 days’ time or less.

This article was written by Christopher Corbett and originally appeared in the April 2006 issue of Wild West.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!